May 29, 2017 | Citizen Science, Risk and resilience

By Wei Liu, IIASA Risk and Resilience Program

What do Rajapur, Nepal; Chosica, Peru; and Tabasco, Mexico all have in common? Flooding: these areas are all threatened by floods, and they also face similar knowledge gaps, especially in terms of local level spatial information on risk, and the resources and the capacities of communities to manage risk.

To address these gaps, I and my colleagues at IIASA, in collaboration with Kathmandu Living Labs (KLL) and Practical Action (PA) Nepal are building on our experiences in Nepal’s Lower Karnali River basin to support flood risk mapping in flood-prone areas in Peru and Mexico.

Recent developments in data collection and communication via personal devices and social media have greatly enhanced citizens’ abilities to contribute spatial data, called Crowdsourced Geographic Information (CGI) in the mapping community. OpenStreetMap is the most widely used platform for sharing this free geographic data globally, and the fast growing Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team has developed CGI in some of the world’s most disaster-prone and data-scarce regions. For example, after the 2015 Nepal Earthquake, thousands of global volunteers mapped infrastructure across Nepal, greatly supporting earthquake rescue, recovery, and reconstruction efforts.

Today there is excellent potential to engage citizen mappers in all stages of the disaster risk management cycle, including risk prevention and reduction, preparedness and reconstruction. In this project, we have successfully launched a series of such mapping activities for the Lower Karnali River basin in Nepal starting in early 2016. In an effort to share the experience and lessons of this work with other Zurich Global Flood Resilience Alliance field sites, in March 2017 we initiated two new mapathons in Kathmandu, with support from Soluciones Prácticas (PA Peru) and the Mexican Red Cross, to remotely map basic infrastructure such as buildings and roads, as well as visible water surface, around flood-prone communities in Chosica, Peru and Tobasco, Mexico.

March 17th, 2017, staff and volunteers conducting remote mapping at Kathmandu Living Labs @ Wei Liu | IIASA

Prior to our efforts very few buildings in these areas were identified on online map portals, including Google Maps, Bing Maps, and OSM. Through our mapathons, dozens of Nepalese volunteers mapped over 15,000 buildings and 100 km of roads. The top scorer, Bishal Bhandari, mapped over 1,700 buildings and 6 km of roads for Chosica alone.

Having the basic infrastructure mapped before a flood event can be extremely valuable for increasing flood preparedness of communities and for local authorities and NGOs. During the period of the mapathons, the Lima region in Peru, including Chosica, was hit by a severe flood induced by coastal El Niño conditions. Having almost all buildings in Chosica mapped on the OSM platform now makes visible the high flood risk faced by people living in this densely populated area with both formal and informal settlements. These data may support conducting a quick damage assessment, as suggested by Miguel Arestegui, a collaborator from PA Peru during his visit to IIASA in April, 2017.

Recognizing the value of crowdsourced spatial risk information, we are working closely with partners, including OpenStreetMap Peru, to mobilize the creativity, technical know-how, and practical experience from the Nepal study to Latin America countries. Collecting such information using CGI comes with low cost but high potential for modeling and estimating the amount of people and economic assets potentially being affected under different future flood situations, for improving development and land-use plans to support disaster risk reduction, and for increasing preparedness and helping with allocating humanitarian support in a timely manner after disaster events.

Having the basic infrastructure mapped before a flood event can be extremely valuable for increasing flood preparedness of communities and for local authorities and NGOs. During the period of the mapathons, the Lima region in Peru, including Chosica, was hit by a severe flood induced by coastal El Niño conditions. Having almost all buildings in Chosica mapped on the OSM platform now makes visible the high flood risk faced by people living in this densely populated area with both formal and informal settlements. These data may support conducting a quick damage assessment, as suggested by Miguel Arestegui, a collaborator from PA Peru during his visit to IIASA in April, 2017.

Recognizing the value of crowdsourced spatial risk information, we are working closely with partners, including OpenStreetMap Peru, to mobilize the creativity, technical know-how, and practical experience from the Nepal study to Latin America countries. Collecting such information using CGI comes with low cost but high potential for modeling and estimating the amount of people and economic assets potentially being affected under different future flood situations, for improving development and land-use plans to support disaster risk reduction, and for increasing preparedness and helping with allocating humanitarian support in a timely manner after disaster events.

Flood-inundated houses and local railway in Chosica, Peru, 18/03/2017 @ Miluska Ordoñez | Soluciones Prácticas

The United Nation’s Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction states that knowledge in “all dimensions of vulnerability, capacity, exposure of persons and assets, hazard characteristics and the environment” needs to be leveraged to inform policies and practices across all stages of the disaster risk management cycle. CGI has a great potential to involve citizens from around the world to help fill this critical knowledge gap. These pilot mapathons conducted between Nepal and Latin America are promising examples of supporting community flood resilience through the mobilization of CGI via international partnerships within the Global South.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Apr 3, 2017 | Demography

By Roman Hoffmann, Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (IIASA, VID/ÖAW and WU), Vienna Institute of Demography, Austrian Academy of Sciences

Flooded street in Meycauayan, Bulacan, Philippines (credit: Kasagana-Ka Development Center Inc., 2016 )

Floods, droughts, and tropical storms have significantly increased, both in frequency and intensity in recent years. The burden of these events—both human and economic—falls in large part on low and middle-income countries with high exposure, such as coastal and island nations. In a recent study, with IIASA researcher Raya Muttarak, we found that education significantly contributes to increasing disaster resilience among poor households in the Philippines and Thailand, two countries which are frequently affected by natural calamities.

In these countries, public disaster risk reduction is important, yet public measures, such as investments in structural mitigation for large buildings or infrastructure, implementation of early warning systems, or planned evacuation routes and shelters, may not be enough to sufficiently protect communities from the devastating impacts of natural calamities. In addition, the undertaking of individual preparedness measures by households, such as stockpiling of food and water, strengthening of house structures, and having a family emergency plan, is crucial. Yet, even in areas which are heavily exposed to disasters, people often do not take any precautionary measures against environmental threats.

How people can be motivated to take precautionary action has been a fundamental question in the field of risk analysis. In the new study, which was based on face-to-face interviews in both Thailand and the Philippines, we found that prior disaster experience, which is influenced by geographical location of the home, is one of the key predictors of disaster preparedness. For those who were affected by a disaster in the recent past, education does not seem to play a significant role—they have already learned by experience. However, among those who had not previously been affected, educational attainment becomes a key determinant. Even without having experienced a disaster, the educated are more likely to make preparations. In fact, educated people who haven’t experienced a disaster have preparedness levels that are as high as those of households who were only recently affected. Since education improves abstract reasoning and abstraction skills, highly educated individuals may not need to experience a disaster to understand that they can be devastating. This suggests that education, as a channel through which individuals can learn about disaster risks and preventive strategies, may effectively serve as a substitute for (often harmful) disaster experiences as a main trigger of preparedness actions.

In additional analyses, we investigated through which channels education promotes disaster preparedness by looking at the relationship between education and different mediating factors such as income, social capital and risk perception, which are likely to influence preparedness actions. We found that how education promotes disaster preparedness is highly context-specific. In Thailand, we found that the highly educated have higher perceptions of disaster risks that can occur in a community as well as higher social capital (measured by engagement in community activities) which in turn increase disaster resilience. In the Philippines, on the other hand, it appears that none of the studied mediating factors explain the effect of education on preparedness behavior.

Emergency shelter, San Mateo, Rizal, Philippines (credit: Kasagana-Ka Development Center Inc., 2013 )

Certainly, it remains important for national governments to invest in disaster risk reduction measures such as early warning systems or evacuation centers. However, our study suggests that public funding in universal education will also benefit precautionary behavior at the personal and household level. In line with recent efforts of the UN to promote education for sustainable development, our study provides solid empirical evidence confirming the important role of education in building disaster resilience in low and middle-income countries.

Reference

Hoffmann, R. & Muttarak, R (2017). Learn from the past, prepare for the future: Impacts of education and experience on disaster preparedness in the Philippines and Thailand. World Development [doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.02.016]

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 27, 2017 | Postdoc, Risk and resilience

By Adam French – Peter E. de Jánosi Postdoctoral Scholar Risk and Resilience and Advanced Systems Analysis Programs

In mid-January, I found myself calling upon rusty rock climbing skills to scramble up a steep side canyon of Peru’s Rimac River valley. I was with a group of engineers and local municipal officials on the way to assess disaster reduction infrastructure that had been installed in early 2016 against the threat of a strong El Niño-enhanced rainy season. The Swiss-made barriers we were going to see, which resembled giant steel spider webs stretched across the streambeds, had been constructed in multiple locations in the Rimac watershed to reduce the destructive impacts of the region’s recurrent but unpredictable huaicos—powerful debris flows that form when precipitation runoff mixes with loose rock and other material on unstable slopes. The 2015-16 El Niño did not live up to its forecasted intensity in Peru, and the barriers went untested until heavy rains in early 2017 unleashed a series of huaicos on the Rimac valley, damaging homes and flooding roadways. Where the barriers were installed, however, no major impacts had been reported, and we were eager to see if the infrastructure had made a difference.

Engineers discuss hazard reduction infrastructure above Chosica, Peru. ©Soluciones Prácticas, Abel Cisneros (Click for more photos)

Most of the time, the Rimac valley looks more like a lunar landscape than a flood-risk hotspot. Yet with only a few millimeters of rain in the surrounding highlands, this arid region becomes extremely vulnerable to huaicos. Located between the sprawling cityscape of Lima—the planet’s second largest desert city—and the lush foothills of the central Andes, the middle reaches of the Rimac watershed have been settled rapidly over recent decades, often without effective zoning regulations to restrict occupation in even the most hazard-prone areas.

I had not planned to work in the Rimac basin when I moved to Austria to take up a postdoctoral position in late 2015. While my research includes the study of climate change-related risk in Peru’s Cordillera Blanca (the world’s most extensively glaciated tropical mountain range), I came to IIASA to focus on watershed-level governance and the implementation of the Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) paradigm. Yet as a Spanish speaker with extensive experience in Peru, I was well suited to get involved in IIASA’s activities in the Rimac valley as part of the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance Project. This project, which includes close collaboration with the NGO Practical Action in Peru and Nepal, supports measures to understand and address the underlying drivers of flood risk and to move beyond short-term disaster preparedness and response towards transformative actions that build long-term capacity and resilience.

As part of IIASA’s Flood Resilience team, my work in the Rimac valley has included activities ranging from evaluating El Niño preparations to conducting interviews with public authorities and local residents living in the Rimac basin. This fieldwork is just part of our project’s efforts to identify the systemic components of flood risk and vulnerability in the region and to promote productive exchanges between residents, policymakers, and the scientific community through participatory research and innovative approaches such as serious gaming.

“Flood Risk Zone,” Ate, Peru. ©Soluciones Prácticas. Click for more photos.

In addition to building expertise in a new setting, my involvement in this work has helped me better incorporate risk-focused systems thinking into my broader research agenda—a perspective that is too often overlooked in integrated resource planning. An example of how my research interests are converging within this project is through the promotion of a risk-management working group to advise the multi-sectorial watershed council in charge of IWRM planning in the Rimac valley. The establishment of this working group and the participation of project partners at Practical Action in its activities should mark an important step in bringing lessons from the Flood Resilience project regarding links between disaster risk reduction, economic development, and community resilience to bear on watershed planning in the Rimac basin. More broadly, we hope these insights will influence policy making in other settings in Peru and beyond that face similar challenges in handling risk management and economic development as intricately linked and co-dependent governance processes.

Returning to our January field inspection, we found that one of the new barriers had been put to the test. The structure had captured several tons of debris, protecting a neighborhood that had been devastated by a huaico in 2015, and local authorities were already discussing the potential to build additional barriers to guard their community. While I celebrated this outcome with them, as I look to the future and the goals of the Flood Resilience Alliance, I am hopeful that such infrastructural interventions will be just one aspect of comprehensive plans for hazard reduction, with long-term risk management actions increasingly seen as a vital component of watershed-level planning and governance.

More information

IIASA, Zurich, Wharton, Practical Action: Flood Resilience Partnership

Flickr photo album: Rimac River valley, Peru – Fieldwork

Flood Resilience Portal

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jan 12, 2017 | Citizen Science, Risk and resilience

By Ian McCallum, IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program

Communities need information to prepare for and respond to floods – to inform risk reduction strategies and strengthen resilience, improve land use planning, and generally prepare for when disaster strikes. But across much of the developing world, data are sparse at best for understanding the dynamics of flood risk. When and if disaster strikes, massive efforts are required in the response phase to develop or update information about basic infrastructure, for example, roads, bridges and buildings. In terms of strengthening community resilience it is important to know about the existence and location of such features as community shelters, medical clinics, drinking water, and more.

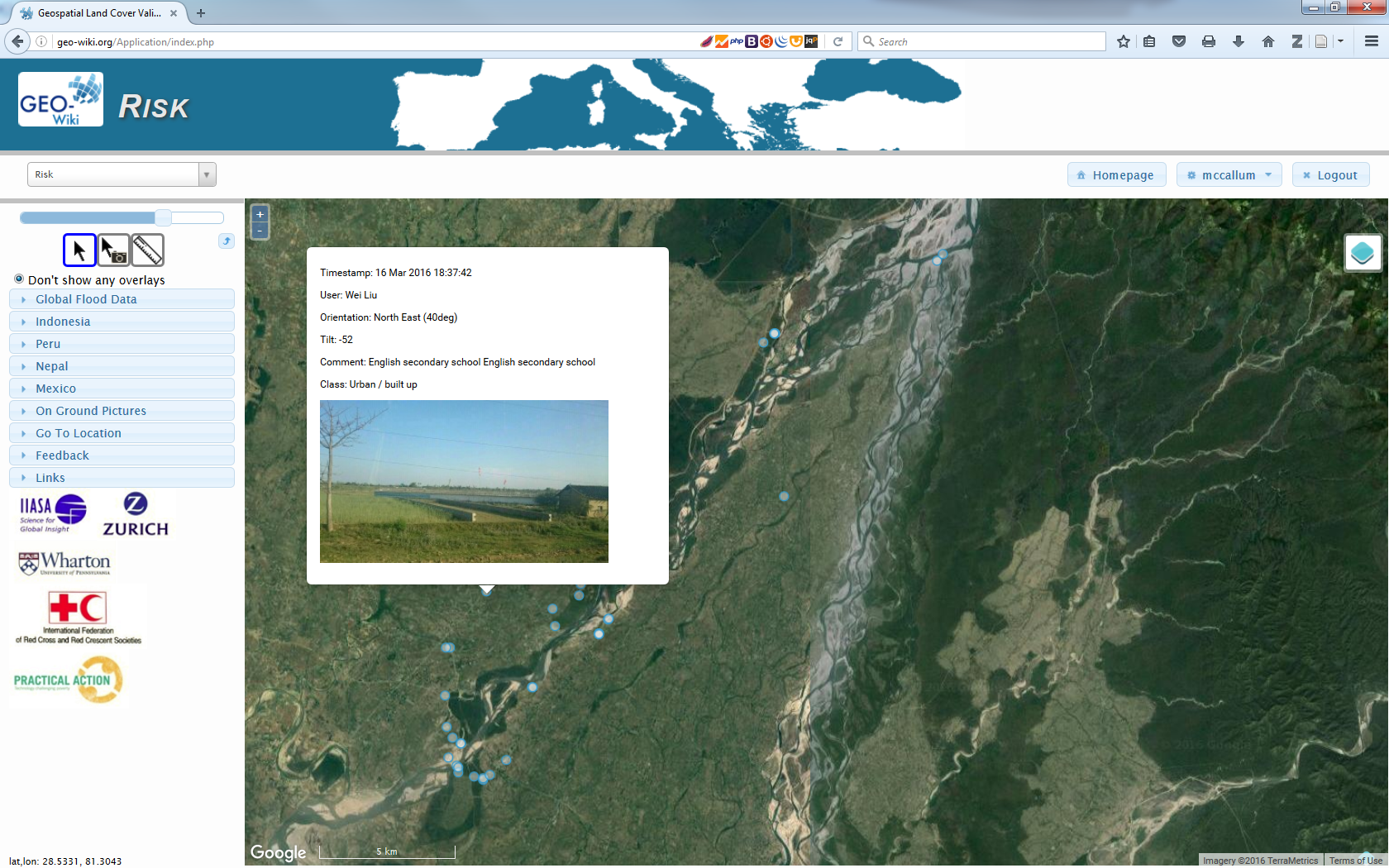

The risk Geo-Wiki platform

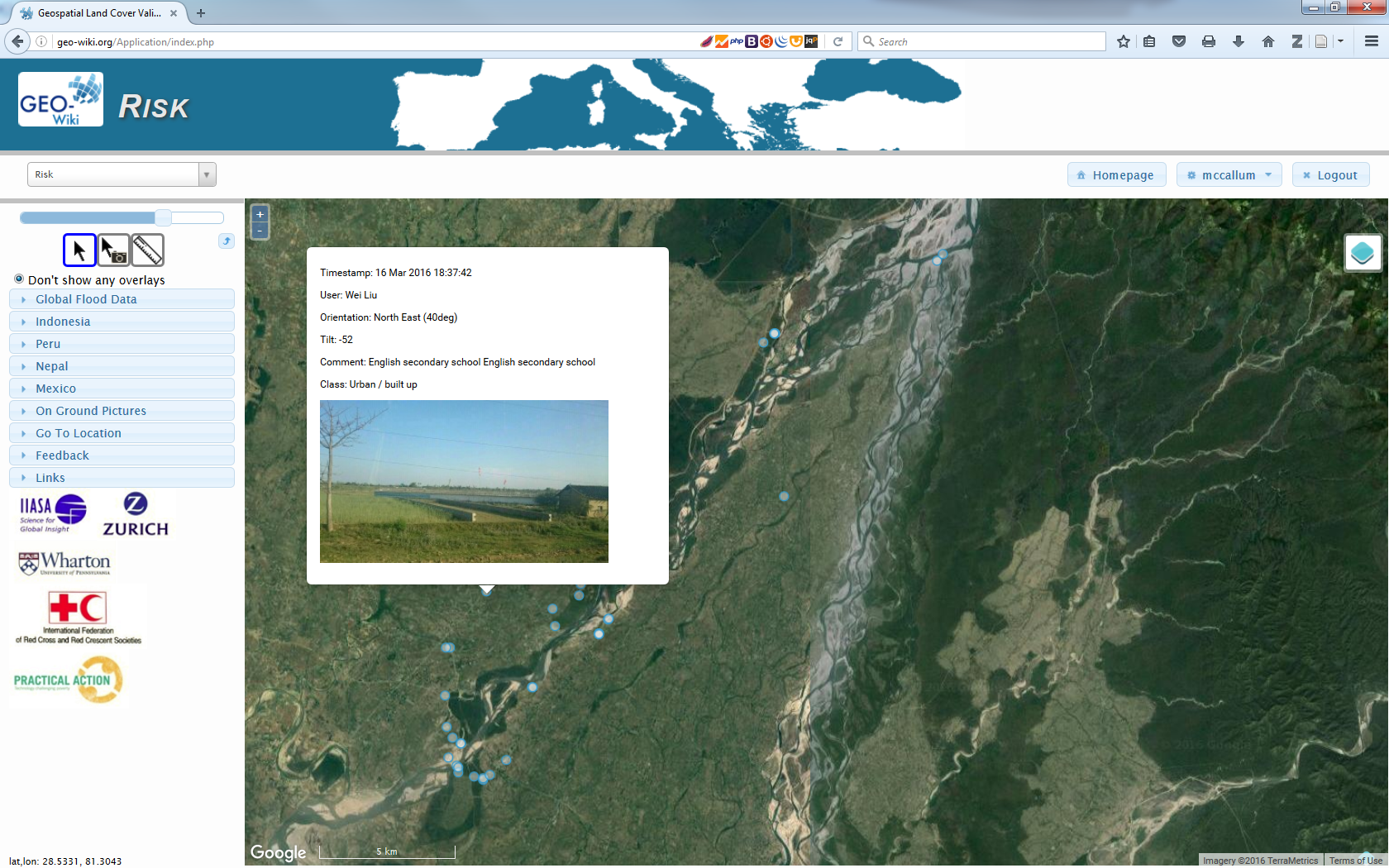

The Risk Geo-Wiki is online platform established in 2014, which acts not only as a repository of available flood related spatial information, but also provides for two-way information exchange. You can use the platform to view available information about flood risk at any location on the globe, along with geo-tagged photos uploaded by yourself or other users via a mobile application Geo-Wiki Pictures. The portal is intended to be of practical use to community leaders and NGOs, governments, academia, industry and citizens who are interested in better understanding the information available to strengthen flood resilience.

The Risk Geo-Wiki showing geo-tagged photographs overlaid upon satellite imagery across the Karnali basin, Nepal. © IIASA

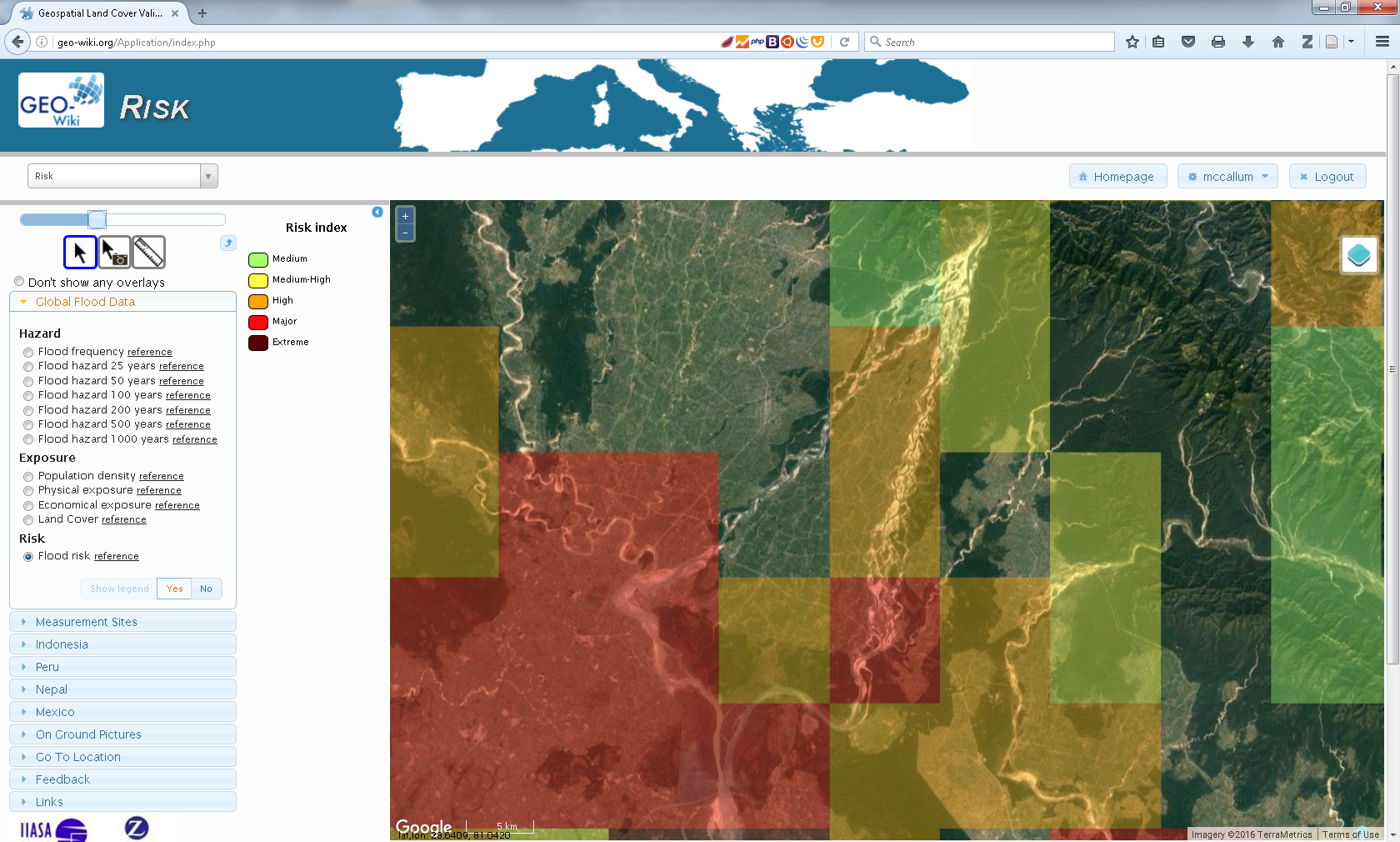

With only a web browser, and a simple registration, anyone can access flood-related spatial information worldwide. Available data range from flood hazard, exposure and risk information, to biophysical and socioeconomic data. All of this information can be overlaid upon satellite imagery or OpenStreetMap, along with on-ground pictures taken with the related mobile application Geo-Wiki Pictures. You can use these data to understand the quality of available global products or to visualize the numerous local datasets provided for specific flood affected communities. People interested in flood resilience will benefit from visiting the platform and are welcome to provide additional information to fill many of the existing gaps in information.

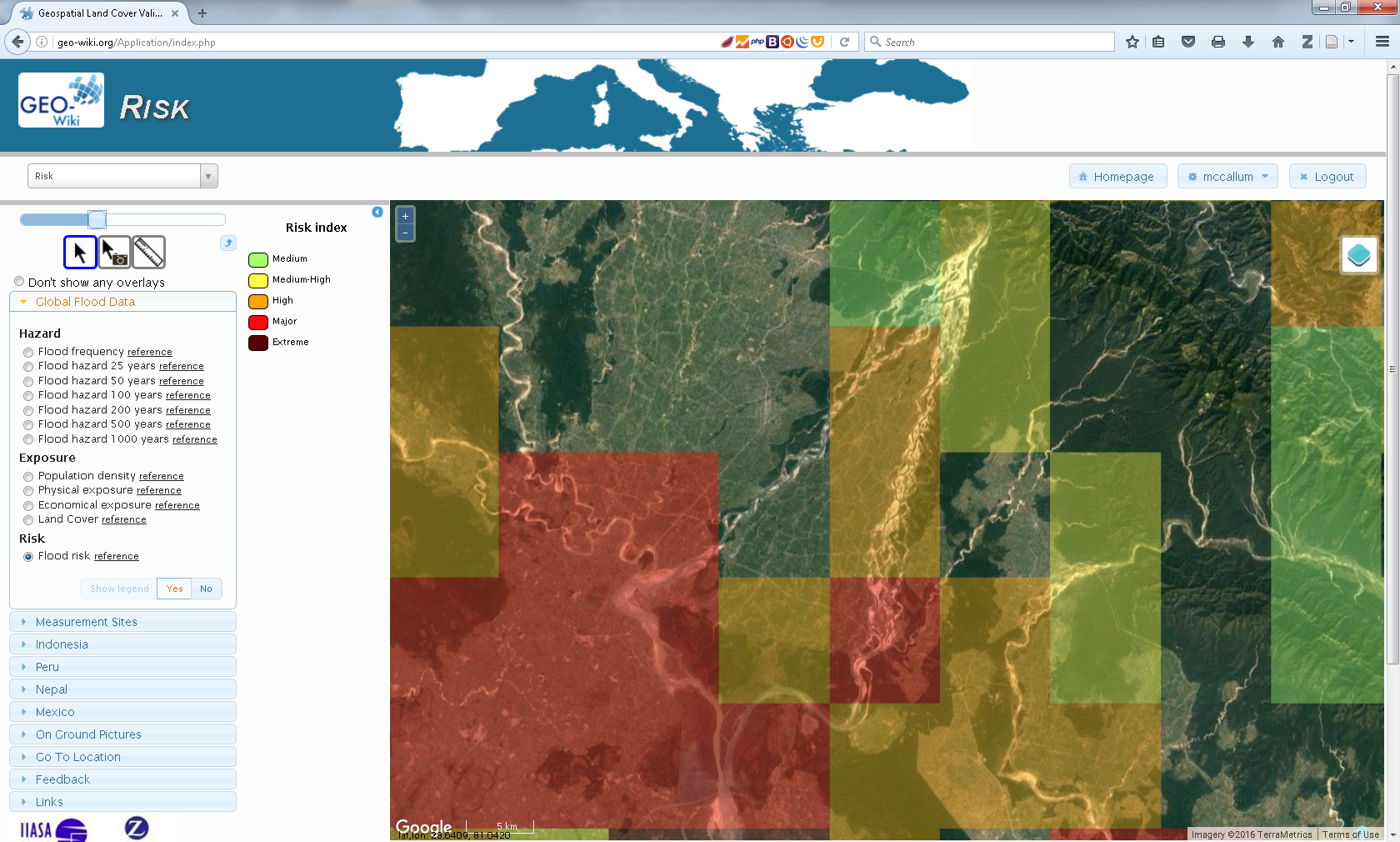

Flood resilience and data gaps

One of the aims of the Risk Geo-Wiki is to identify and address data gaps on flood resilience and community-based disaster risk reduction. For example, there is a big disconnect between information suitable for global flood risk modelling and that necessary for community planning. Global modelers need local information with which to validate their forecasts while community planners want both detailed local information and an understanding of their communities in the wider region. The Flood Resilience Alliance is working with many interested groups to help fill this gap and at the same time help strengthen community resilience against floods and to develop and disseminate knowledge and expertise on flood resilience.

The Risk Geo-Wiki showing modelled global flood risk data overlaid at community level. While this data is suitable at the national and regional level, it is too coarse for informing community level decisions. © IIASA

Practical applications for local communities

Already, communities in Nepal, Peru, and Mexico have uploaded data to the site and are working with us on developing it further. For local communities who have uploaded spatial information to the site, it allows them to visualize their information overlaid upon satellite imagery or OpenStreetMap. Furthermore, if they have used Geo-Wiki Pictures to document efforts in their communities, these geo-tagged photos will also be available.

Community and NGO members mapping into OSM with mobile devices in the Karnali basin, Nepal. © Wei Liu, IIASA

In addition to local communities who have uploaded information, the Risk Geo-Wiki will provide important data to others interested in flood risk, including researchers, the insurance industry, NGOs, and donors. The portal provides a source of information that is both easily visualized and overlaid on satellite imagery with local images taken on the ground if available. Such a platform allows anyone interested to better understand flood events over their regions and communities of interest. It is, however, highly dependent upon the information that is made available to the platform, so we invite you to contribute. In particular if you have geographic information related to flood exposure, hazard, risk and vulnerability in the form of images or spatial data we would appreciate you getting in contact with us.

About the portal:

The Risk Geo-Wiki portal was established by the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) in the context of the Flood Resilience Alliance. It was developed by the Earth Observation Systems Group within the Ecosystems Services and Management Program at IIASA.

Further information

- Risk Geo-Wiki

- Collection of geo-tagged photos with Geo-Wiki Pictures

- Mapping flood resilience in rural Nepal

- Flood Resilience Portal

- McCallum, I., Liu, W., See, L., Mechler, R., Keating, A., Hochrainer-Stigler, S., Mochizuki, J., Fritz, S., Dugar, S., Arestegui, M., Szoenyi, M., Laso Bayas, J.C., Burek, P., French, A. and Moorthy, I. (2016) Technologies to Support Community Flood Disaster Risk Reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 7 (2). pp. 198-204.http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/13299/

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 10, 2016 | Risk and resilience

By Wei Liu, IIASA Risk and Resilience and Ecosystems Services and Management programs

Disasters caused by extreme weather events are on the rise. Floods in particular are increasing in frequency and severity, with reoccurring events trapping people in a vicious cycle of poverty. Information is key for communities to prepare for and respond to floods – to inform risk reduction strategies, improve land use planning, and prepare for when disaster strikes.

But, across much of the developing world, data is sparse at best for understanding the dynamics of flood risk. When and if disaster strikes, massive efforts are required in the response phase to develop or update information. After that, communities have an even greater need for data to help with recovery and reconstruction and further enhance communities’ resilience to future floods. This is particularly important for the Global South, such as the Karnali Basin in Nepal, where little information is available regarding community’s exposure and vulnerability to floods.

Karnali Basin in Nepal © Wei Liu | IIASA

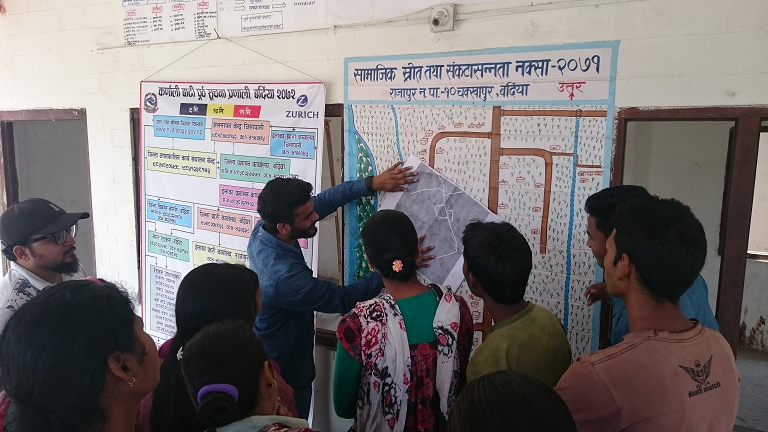

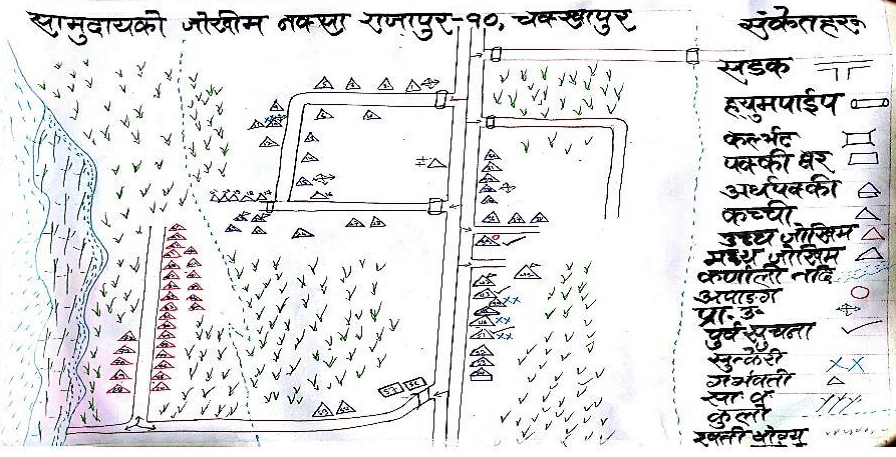

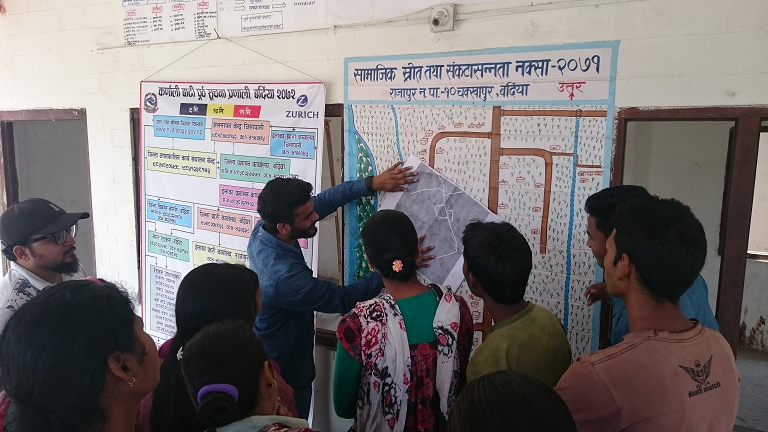

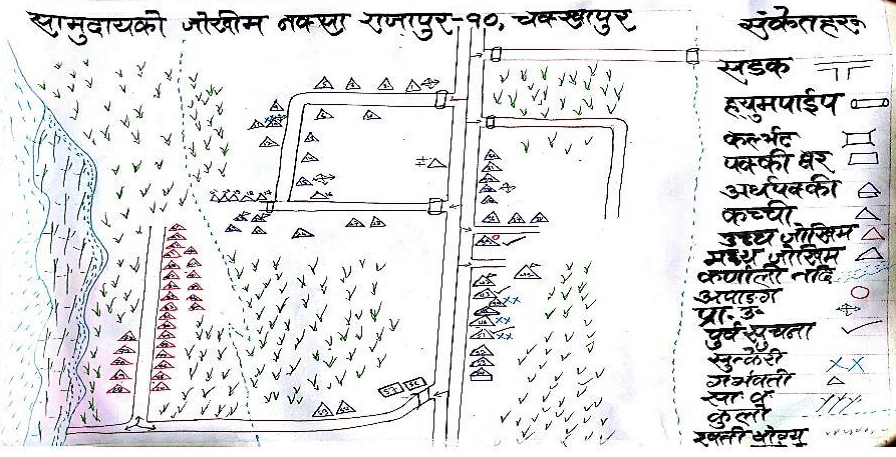

That’s why we are working with Practical Action in the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance to try to remedy this situation. Participatory Vulnerability and Capacity Assessment is a widely used tool to collect community level disaster risk and resilience information and to inform disaster risk reduction strategies. One of our first projects was to digitize a set of existing maps on disaster risk and community resources where the locations of, for example, rivers, houses, infrastructure and emergency shelters are usually hand-drawn by selected community members. Such maps provide critical information used by local stakeholders in designing and prioritizing among possible flood risk management options.

From hand-drawn to internet mapping

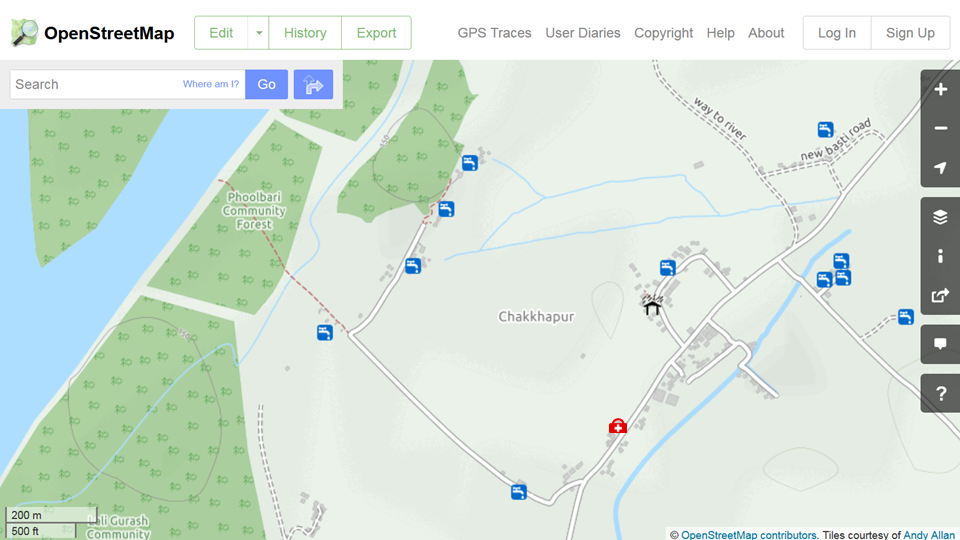

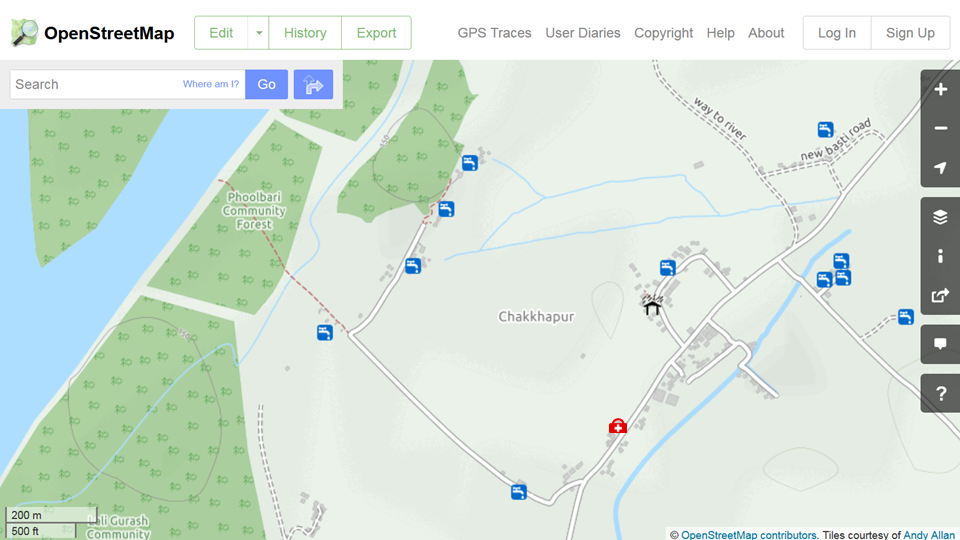

While hand-drawn maps are ideal for working in remote rural communities, they risk being damaged, lost, or simply unused. They are also more difficult to share with other stakeholders such as emergency services or merge with additional mapped information such as flood hazard. With the recent increase in internet mapping, platforms such as OpenStreetMap have made it possible for us to transfer existing maps or capture new information on a common platform in such a way that anyone with an internet connection can add, edit, and share maps. As this information is digital, it makes it easier to perform additional tasks, such as identifying households in areas of high risk or measuring the distance to the nearest emergency shelter, to support effective risk-reduction and resilience-building.

Practical Action Nepal, the Center for Social Development and Research, and community members discuss the transfer of community maps to online maps © Wei Liu | IIASA

From theory to practice

In March 2016, the Project team travelled to two Nepal communities in the Rajapur and Tikapur districts, to pilot the idea of working with a local NGO (the Center for Social Development and Research) and community members, to transfer their maps into a digital environment. The latter can easily be further edited, improved and shared within a broad range of stakeholders and potential users. Local residents in both communities were excited seeing their households and other features for the first time overlaid on a map with satellite imagery. The Center for Social Development and Research was also very enthusiastic about integrating their future community mapping activities with digital mapping, without losing the spirit of participation.

Hand drawn maps produced from community mapping exercises in Chakkhapur, Nepal © Practical Action

The resulting online maps in OpenStreetMap of Chakkhapur, Nepal, showing the location of drinking water, an emergency shelter and medical clinic. ©OpenStreetMap

Increasing resilience through improved information management

The first stage pilot study in the Karnali river basin confirmed the great potential of new digital technologies in providing accurate and locally relevant maps to improve flood risk assessment to support resilience building at the community level. The next step is to further engage local stakeholders. A wider partnership has been established between Practical Action, the Center for Social Development and Research, the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis and Kathmandu Living Labs to further build local stakeholders’ capacity in mapping with digital technologies, including a training workshop for NGO staff members in September, 2016. The plan is to have more communities’ flood risk information mapped for designing more effective action plans and strategies for coping with future flood events across the Karnali river basin. A greater potential can be realized when this effort is further scaled up across the region and the results are placed into shared open online databases such as OpenStreetMap.

Further information

- Flood Resilience Portal

- Geo-Wiki Risk

- McCallum, I., Liu, W., See, L., Mechler, R., Keating, A., Hochrainer-Stigler, S., Mochizuki, J., Fritz, S., Dugar, S., Arestegui, M., Szoenyi, M., Laso Bayas, J.C., Burek, P., French, A. and Moorthy, I. (2016) Technologies to Support Community Flood Disaster Risk Reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 7 (2). pp. 198-204. http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/13299/

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.