Jul 24, 2018 | Education, Sustainable Development, Women in Science

By Stephanie Bengtsson, researcher in the IIASA World Population Program

In the months after finishing my doctorate, I would often find myself having some variation of the following conversation upon meeting someone new, particularly in a social context:

New person: “So, what do you do?”

Me: “Actually, I’ve just finished my doctorate.”

New person [impressed]: “Wow! In what field?”

Me: “Education.”

New person [after a long pause]: “Oh.”

The tone of that “oh” has stayed with me in the years since: “You can get a doctorate in education?”, that little word seemed to say, following up with: “What does that involve? Stacking ABC blocks and looking through picture books? It can’t possibly be as challenging as a doctorate in a real subject, like economics or neuroscience.”

Many of my education colleagues around the world have had similar experiences, especially those who, like me, work primarily in the field of development. At the same time, the global news media is rife with articles about ‘failing’ school systems, a dwindling ‘supply’ of qualified teachers, ‘underperforming’ teachers, low Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) results, and more, as the international community searches for quick-fix solutions with easily quantifiable measures of progress to address these problems, often outside the realm of education research. Generally, within the dominant development discourse, the aim of these solutions is clear: to increase attainment and improve student test scores, particularly in the so-called STEM subjects (i.e., Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics), in order to build human capital and subsequently grow and sustain the labor market and economy. In other words, improvements to education are typically justified only to the extent that they will increase education’s instrumental value (leading to improvements in other sectors), rather than its intrinsic value.

As such, those of us working in international educational development often find ourselves caught in a paradox, as our sector has been (and continues to be) simultaneously under-appreciated in terms of the contribution it can make to other aspects of development and wellbeing (and subsequently under-prioritized), and over-emphasized in its role as a tool of development when it does make it onto the agenda. We therefore frequently find ourselves having to first ‘make the business case’ for education by proving its instrumental value before beginning any research or development project, in a way that would be considered ludicrous in, for instance, the sectors of health and nutrition. Once we have successfully argued that case, the pressure is on to measure inputs and narrowly-defined short-term outcomes, leaving little time to examine complex educational processes and longer-term impacts of education.

In late September 2015, Heads of State and High Representatives from around the world committed to a new sustainable development agenda consisting of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and 169 accompanying targets. The framing document for the SDGs, UN Resolution 70/1, Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, envisions an important role for education within this agenda, both as an end and a powerful means of development:

“All people, irrespective of sex, age, race, ethnicity, and persons with disabilities, migrants, indigenous peoples, children and youth, especially those in vulnerable situations, should have access to life-long learning opportunities that help them acquire the knowledge and skills needed to exploit opportunities and to participate fully in society. We will strive to provide children and youth with a nurturing environment for the full realization of their rights and capabilities, helping our countries to reap the demographic dividend including through safe schools and cohesive communities and families.” (UN 2015, article 25)

For those of us working in international educational development, the SDGs thus represent a significant step forward from the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), as well as an opportunity to encourage the wider development community to engage with and invest in a shared vision for equitable, inclusive, quality lifelong learning opportunities.

In our new book, The Role of Education in Enabling the Sustainable Development Agenda, my colleagues and I conduct an extensive critical review of literature from a range of disciplines, attempting to find answers to these fundamental questions about the value of education and the dynamic nature of the relationship between education and development. We engage with the argument put forward in the capabilities approach to development that the capability to be educated is, in and of itself, an important freedom, and a fundamental aspect of human wellbeing. Given that processes of teaching and learning are a natural and defining characteristic of human society, we argue that education is most successful at contributing to sustainable development across all dimensions at once if, rather than being crafted as an instrument to achieve a specific and narrow development objective – no matter how worthy – education is improved on its own terms, and as an end in itself.

We also draw from recent work by the economist Kate Raworth, which attempts to connect the economic, social, and environmental dimensions of sustainable development, by combining social justice work with planetary boundaries research in order to define a space within which humanity can survive and thrive:

“Between a social foundation that protects against critical human deprivations, and an environmental ceiling that avoids critical natural thresholds, lies a safe and just space for humanity [. . .] where both human wellbeing and planetary wellbeing are assured, and their interdependence is respected.” (Raworth 2012, p. 7)

This book builds on work we carried out for the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report, and shares in UNESCO’s urgent sense of purpose to demonstrate not only “the potential for education to propel progress towards all global goals”, but also that “education needs a major transformation to fulfil that potential and meet the current challenges facing humanity and the planet” (UNESCO n.d., n.p.). At no point do we claim to be providing the definitive account of the role of education in the sustainable development agenda; rather, we hope that our book will inspire critical reflection, engagement, and, above all, learning, among a wide audience of scholars, students, policymakers, and practitioners alike.

References

Harber, C. (2014). Education and international development: Theory, practice and issues. Oxford: Symposium Books.

Raworth, K. (2012). A safe and just space for humanity: Can we live within the doughnut? Oxfam Discussion Paper. Oxford: Oxfam.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as Freedom. New York: Knopf.

UNESCO. (n.d). Education needs to change fundamentally to meet global development goals. Retrieved from: www.unesco.org/new/en/education/themes/leading-the-international-agenda/education-for-all/single-view/news/education_needs_to_change_fundamentally_to_meet_global_devel/

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 30, 2018 | Economics, Food & Water, Sustainable Development, Systems Analysis

By Alan Nicol, Strategic Program Leader at the International Water Management Institute (IWMI)

I was at the local corner store in Uganda last week and noticed the profusion of rice being sold, the origin of which was from either India or Pakistan. It is highly likely that this rice being consumed in Eastern Africa, was produced in the Indus Basin, using Indus waters, and was then processed and shipped to Africa. That is not exceptional in its own right and is, arguably, a sign of a healthy global trading system.

Nevertheless, the rice in question is likely from a system under increasing stress, one that is often simply viewed as a hydrological (i.e., basin) unit. What my trip to the corner store shows is that perhaps more than ever before a system such as the Indus is no longer confined–it extends well beyond its physical (hydrological) borders.

Not only does this rice represent embedded ‘virtual’ water (the water used to grow and refine the produce), but it also represents policy decisions, embedded labor value, and the gamut of economic agreements between distribution companies and import entities, as well as the political relationship between East Africa and South Asia. On top of that are the global prices for commodities and international market forces.

In that sense, the Indus River Basin is the epitome of a complex system in which simple, linear causality may not be a useful way for decision makers to determine what to do and how to invest in managing the system into the future. Integral to this biophysical system, are social, economic, and political systems in which elements of climate, population growth and movement, and political uncertainty make decisions hard to get right.

Like other systems, it is constantly changing and endlessly complex, representing a great deal of interconnectivity. This poses questions about stability, sustainability, and hard choices and trade-offs that need to be made, not least in terms of the social and economic cost-benefit of huge rice production and export.

An aerial view of the Indus River valley in the Karakorum mountain range of the Basin. © khlongwangchao | Shutterstock

So how do we go about planning in a system that is in such constant flux?

Coping with system complexity in the Indus is the overarching theme of the third Indus Basin Knowledge Forum (IBKF) being co-hosted this week by the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), and the World Bank. Titled Managing Systems Under Stress: Science for Solutions in the Indus Basin, the Forum brings together researchers and other knowledge producers to interface with knowledge users like policymakers to work together to develop the future direction for the basin, while improving the science-decision-making relationship. Participants from four riparian countries–Afghanistan, China, India, and Pakistan–as well as from international organizations that conduct interdisciplinary research on factors that impact the basin, will work through a ‘marketplace’ for ideas, funding sources, and potential applications. The aim is to narrow down a set of practical and useful activities with defined outcomes that can be tracked and traced in coming years under the auspices of future fora.

The meeting builds on the work already done and, crucially, on relations already established in this complex geopolitical space, including under the Indus Forum and the Upper Indus Basin Network. By sharing knowledge, asking tough questions, and identifying opportunities for working together, the IBKF hopes to pin down concrete commitments from both funders and policymakers, but also from researchers, to ensure high quality outputs that are of real, practical relevance to this system under stress–from within and externally.

Scenario planning

Feeding into the IBKF3, and directly preceding the forum, the Integrated Solutions for Water, Energy, and Land Project (ISWEL) will bring together policymakers and other stakeholders from the basin to explore a policy tool that looks at how best to model basin futures. This approach will help the group conceive possible futures and model the pathways leading to the best possible outcomes for the most people. This ‘policy exercise approach’ will involve six steps to identify and evaluate possible future pathways:

- Specifying a ‘business as usual’ pathway

- Setting desirable goals (for sustainability pathways)

- Identifying challenges and trade-offs

- Understanding power relations, underlying interests, and their role in nexus policy development

- Developing and selecting nexus solutions

- Identifying synergies, and

- Building pathways with key milestones for future investments and implementation of solutions.

The summary of this scenario development workshop and a vision for the Indus Basin will be shared as part of the IBKF3 at the end of the event, and will help the participants collectively consider what actions can be taken to ensure a prosperous, sustainable, and equitable future for those living in the basin.

The rice that helps feed parts of East Africa plays a key global role–the challenge will be ensuring that this important trading relationship is not jeopardized by a system that moves from pressure points to eventual collapse. Open science-policy and decision-making collaboration are key to making sure that this does not happen.

This blog was originally published on https://wle.cgiar.org/thrive/2018/05/29/rice-and-reason-planning-system-complexity-indus-basin.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 28, 2018 | Air Pollution, Climate, Climate Change, Ecosystems, Energy & Climate, Women in Science

By Beatriz Mayor, Research Scholar at IIASA

On 14 and 15 May, Vienna hosted two important events within the frame of the world energy and climate change agendas: the Vienna Energy Forum and the R20 Austrian World Summit. Since I had the pleasure and privilege to attend both, I would like to share some insights and relevant messages I took home with me.

Beatriz Mayor at the Austrian World Summit © Beatriz Mayor

To begin with, ‘renewable energy’ was the buzzword of the moment. Renewable energy is not only the future, it is the present. Recently, 20-year solar PV contracts were signed for US$0.02/kWh. However, renewable energy is not only about mitigating the effects of climate change, but also about turning the planet into a world we (humans from all regions, regardless of the local conditions) want to live in. It is not only about producing energy, about reaching a number of KWh equivalent to the expected demand–renewables are about providing a service to communities, meeting their needs, and improving their ways of life. It does not consist only of taking a solar LED lamp to a remote rural house in India or Africa. It is about first understanding the problem and then seeking the right solution. Such a light will be of no use if a mother has to spend the whole day walking 10 km to find water at the closest spring or well, and come back by sunset to work on her loom, only to find that the lamp has run out of battery. Why? Because her son had to take it to school to light his way back home.

This is where the concept of ‘nexus’ entered the room, and I have to say that more than once it was brought up by IIASA Deputy Director General Nebojsa Nakicenovic. A nexus approach means adopting an integrated approach and understanding both the problems and the solutions, the cross and rebound effects, and the synergies; and it is on the latter that we should focus our efforts to maximize the effect with minimal effort. Looking at the nexus involves addressing the interdependencies between the water, energy, and food sectors, but also expanding the reach to other critical dimensions such as health, poverty, education, and gender. Overall, this means pursuing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Vienna Energy Forum banner created by artists on the day © UNIDO / Flickr

Another key word that was repeatedly mentioned was finance. The question was how to raise and mobilize funds for the implementation of the required solutions and initiatives. The answer: blended funding and private funding mobilization. This means combining different funding sources, including crowd funding and citizen-social funding initiatives, and engaging the private sector by reducing the risk for investors. A wonderful example was presented by the city of Vienna, where a solar power plant was completely funded (and thus owned) by Viennese citizens through the purchase of shares.

This connects with the last message: the importance of a bottom-up approach and the critical role of those at the local level. Speakers and panelists gave several examples of successful initiatives in Mali, India, Vienna, and California. Most of the debates focused on how to search for solutions and facilitate access to funding and implementation in the Global South. However, two things became clear. Firstly, massive political and investment efforts are required in emerging countries to set up the infrastructural and social environment (including capacity building) to achieve the SDGs. Secondly, the effort and cost of dismantling a well-rooted technological and infrastructural system once put in place, such as fossil fuel-based power networks in the case of developed countries, are also huge. Hence, the importance of emerging economies going directly for sustainable solutions, which will pay off in the future in all possible aspects. HRH Princess Abze Djigma from Burkina Faso emphasized that this is already happening in Africa. Progress is being made at a critical rate, triggered by local initiatives that will displace the age of huge, donor-funded, top-down projects, to give way to bottom-up, collaborative co-funding and co-development.

Overall, if I had to pick just one message among the information overload I faced over these two days, it would be the statement by a young fellow in the audience from African Champions: “Africa is not underdeveloped, it is waiting and watching not to repeat the mistakes made by the rest of the world.” We should keep this message in mind.

Mar 15, 2018 | Poverty & Equity, Women in Science

Monika Bauer, IIASA Alumni Officer

International Women’s Day is celebrated worldwide every year on 8 March. The event aims to promote the work and rights of women. This year, IIASA celebrated International Women’s Day with a panel discussion which asked the question, “Can a women-empowered world resolve some of the global sustainability challenges?” IIASA Population Researcher Raya Muttarak, moderated the panel that included Tyseer Aboulnasr, Melody Mentz, Shonali Pachauri, and Mary Scholes.

“The IIASA Women in Science Club chose this topic because it would allow the panelists to reflect on the potential welfare benefits of a more gender-balanced world. We wanted to know if balance could benefit both women and men, and we wanted to provide a space to discuss the potential intersectionality of the challenges to female empowerment such as poverty, racism, sexism, access to education, health autonomy, and resource inequality,” said organizer Amanda Palazzo, IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management researcher.

IIASA Director General and CEO Professor Dr. Pavel Kabat opened the discussion by offering a brief history of International Women’s Day in the context of the early history of IIASA.

Melody Mentz gives her thoughts

Mentz, an independent higher education research and evaluation consultant based in South Africa, spoke about the implications that a gender-balanced world could hold for science and sustainability using the African agricultural system as an example. To this end, she presented a few statistics that show how the African food system intersects with the sustainable development goal of gender equality.

According to the most recent Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations study, women do up to 50 % of agricultural labor in Africa (this varies by country). Bearing this fact in mind, women however, own only 10 % of the land in Africa; they receive less than 10% of the investments in agriculture on the continent; and less than 5% of women have access to advisory services. In addition, they hold just 14% of management positions in the sector, and only one in four agricultural researchers on the continent is female.

“There is a huge disparity between the contributions of women, the impact of the current food system on women, and the role that the environment allows them to play,” explained Mentz.

As far as the implications of this are concerned, the first, and perhaps the most obvious, is that we need more women in science. Secondly, according to Mentz, we also need more science for women.

“At an institutional level we [should] start thinking differently about what kind of questions we answer. Those questions don’t have to be focused on women, but rather, should consider the implications for both men and women,” she said.

Thirdly, she argued for more science with women, as many research questions and research designs are not just driven by scientists, but actually originate with the people that researchers are trying to help. Finally, we also need more science about women, meaning that data and indicators of impact need to include gender, especially in the context of Africa.

IIASA Energy Researcher Pachauri reflected on the inequalities that we see in our everyday lives. Her work specializes in household energy access in the developing world. Pachauri shared an example from an organization called ENERGIA, of which she is a member of the advisory board, where women were included as microentrepreneurs in the delivery of energy in villages. The organization found that female entrepreneurs were more successful and profitable than the men, which they put down to a greater use of social networks and relationships. The example demonstrated how societies can benefit from including women in solutions for everyday problems.

Aboulnasr, a retired electrical engineering professor, focused on the importance of balance – whether it is a balance of genders, social classes, or geography. Aboulnasr eloquently suggested that rather than striving for perfect balance, one should accept a more dynamic and changing balance. She also stated that one should focus on the impact, rather than on the tools. For example, excellent science is a tool for reaching a goal that makes an impact, rather than excellence in science being the goal. Her advice to the audience was to be open to accepting failure in one’s life.

“If you don’t fail in 30% of what you attempt to do, then you have never reached your limits,” she said, and encouraged the audience to stop obsessing about the failures of the past, seek balance, and to not feel guilty.

Scholes, a professor at the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa, approached the question of the day differently. She urged the audience to look at the question from a sustainability perspective, and to ask what role gender has to play in stewardship for the planet. In addition, she asked the audience to consider whether our unstainable use of resources is because of gender inequality, or because of a more underlying misalignment of values, and what type of empowerment might be needed to achieve a more sustainable world.

“As far as we know, this is the first panel discussion hosted at IIASA which has specifically tried to examine the role of women in achieving a sustainable future. We learned that there are pockets of IIASA research already exploring this this issue and that there is room and interest to engage in this discussion in the future,” says Palazzo.

It is clear that there is no simple answer to the issues surrounding the topic of our International Women’s Day panel discussion. The event however, highlighted unique reflections and experiences from each panelist, and the IIASA Women in Science Club will continue to explore and push the discussion forward. We look forward to updating you soon.

Some of of the panel discussion attendees wearing red, purple and black themed clothes for International Women’s Day

Jan 22, 2018 | Energy & Climate, Poverty & Equity

By Narasimha Rao, Project Leader of the Decent Living Energy (DLE) Project, IIASA Energy Program

Is there a conflict between reducing global income inequality and combating climate change? This seems like an odd question, given that these challenges have a lot in common. Raising the living standard of the poor for example, makes them resilient to climate impacts; less inequality can mean more political mobilization to establish climate policies; and changes in social norms away from material accumulation can reduce inequality and emissions. Academics have however been curious about the following phenomenon: In many countries, a dollar spent at higher income levels is less energy intensive than at lower income levels (known as “income elasticity of energy”). That is, rich people – although they consume much more in total – spend additional income on services or can afford energy-efficient goods, while the new middle class buy energy-intensive goods, like appliances and cars.

Many imagine China as a template for this type of fast growth. If globally significant, this effect would imply that growth that is more equitable would also be more emissions-intensive, and that we would have to pay particular attention to ensuring that climate policies reach the rising middle class in developing countries. While several studies have examined this phenomenon in specific countries, no one has examined its global significance. We set out to do that.

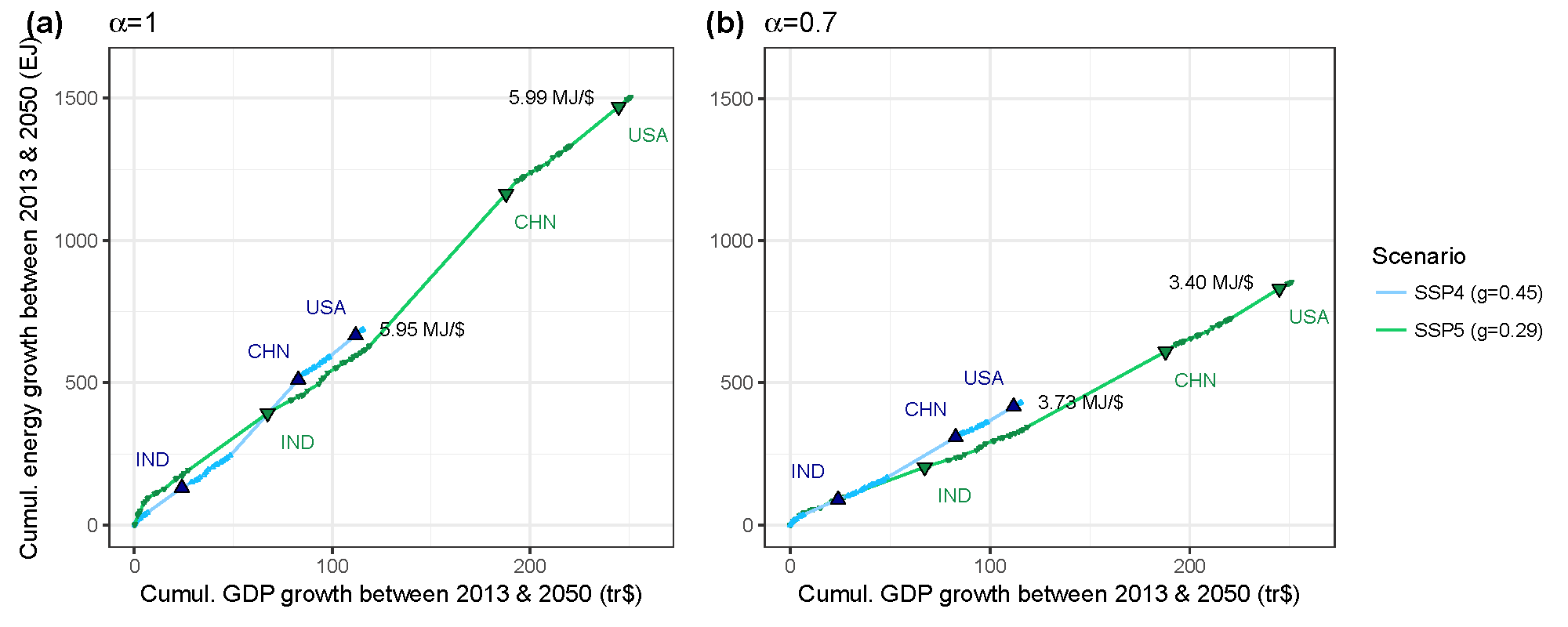

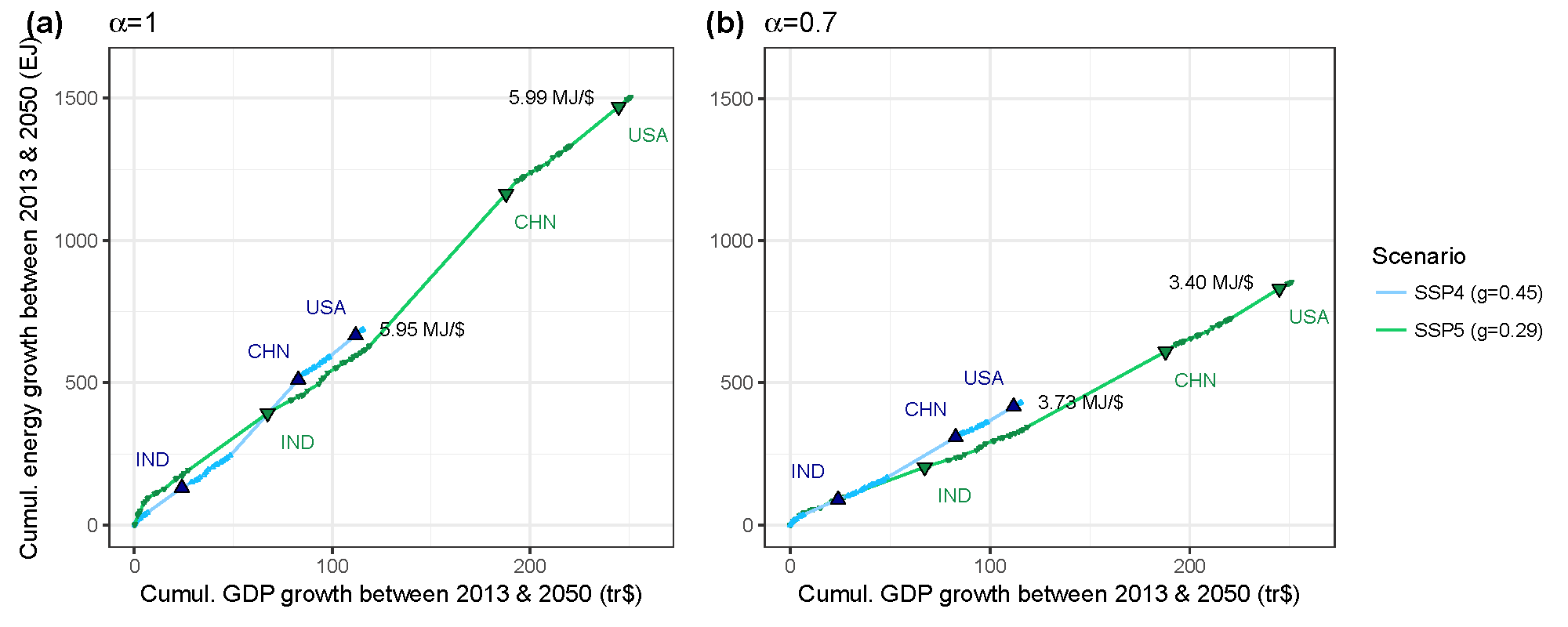

Energy intensity (MJ per $) lower in a high-growth, low inequality world (green line, Gini=0.29) compared to a low-growth, high inequality world (blue line, Gini=0.45). Gini reflects between-country inequality only.

Our analysis suggests that the energy-increasing effect of lowering inequality is more of a distraction than a concern. We compared scenarios of equitable and inequitable income growth, both within and between countries, assuming the most extreme manifestation of the income elasticity. Within any country, given the slow pace at which inequality typically evolves even with the most extreme known income elasticity and reduction in country inequality, greenhouse gas emissions would increase by less than 8% over a couple of decades. However, when one considers a more equitable distribution of growth between countries, global emissions growth may decrease when compared to growth that occurs in industrialized countries. This is because poorer countries have more potential for technological advancements that reduce the energy intensity of growth than richer countries do. That is, more income growth in poorer countries provides more opportunity for efficiency improvements that influence the emissions of very large populations. Furthermore, China is a poor model for poor countries at large, many of which have relatively low energy intensities, even today.

Climate stabilization at the level aspired to by the Paris Climate Agreement requires that we (i.e. the world) decarbonize to zero annual emissions around 2050, which means that even developing countries have to make aggressive strides towards integrating climate goals into development. Nevertheless, there is no sufficient basis for considering that equitable growth, and by implication the poor’s energy intensity, is part of the problem. To the contrary, the potential for co-benefits from equitable growth for climate change are enormous, but unfortunately under-explored, particularly in quantitative studies. Research should focus on quantifying the role of changing social norms – less consumerism, political mobilization, and other social changes that are typically associated with lower inequality – on reducing greenhouse gases.

Reference:

Rao, ND, Min J. Less global inequality can improve climate outcomes. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change. 2018;e513. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.513

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.