Mar 15, 2018 | Poverty & Equity, Women in Science

Monika Bauer, IIASA Alumni Officer

International Women’s Day is celebrated worldwide every year on 8 March. The event aims to promote the work and rights of women. This year, IIASA celebrated International Women’s Day with a panel discussion which asked the question, “Can a women-empowered world resolve some of the global sustainability challenges?” IIASA Population Researcher Raya Muttarak, moderated the panel that included Tyseer Aboulnasr, Melody Mentz, Shonali Pachauri, and Mary Scholes.

“The IIASA Women in Science Club chose this topic because it would allow the panelists to reflect on the potential welfare benefits of a more gender-balanced world. We wanted to know if balance could benefit both women and men, and we wanted to provide a space to discuss the potential intersectionality of the challenges to female empowerment such as poverty, racism, sexism, access to education, health autonomy, and resource inequality,” said organizer Amanda Palazzo, IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management researcher.

IIASA Director General and CEO Professor Dr. Pavel Kabat opened the discussion by offering a brief history of International Women’s Day in the context of the early history of IIASA.

Melody Mentz gives her thoughts

Mentz, an independent higher education research and evaluation consultant based in South Africa, spoke about the implications that a gender-balanced world could hold for science and sustainability using the African agricultural system as an example. To this end, she presented a few statistics that show how the African food system intersects with the sustainable development goal of gender equality.

According to the most recent Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations study, women do up to 50 % of agricultural labor in Africa (this varies by country). Bearing this fact in mind, women however, own only 10 % of the land in Africa; they receive less than 10% of the investments in agriculture on the continent; and less than 5% of women have access to advisory services. In addition, they hold just 14% of management positions in the sector, and only one in four agricultural researchers on the continent is female.

“There is a huge disparity between the contributions of women, the impact of the current food system on women, and the role that the environment allows them to play,” explained Mentz.

As far as the implications of this are concerned, the first, and perhaps the most obvious, is that we need more women in science. Secondly, according to Mentz, we also need more science for women.

“At an institutional level we [should] start thinking differently about what kind of questions we answer. Those questions don’t have to be focused on women, but rather, should consider the implications for both men and women,” she said.

Thirdly, she argued for more science with women, as many research questions and research designs are not just driven by scientists, but actually originate with the people that researchers are trying to help. Finally, we also need more science about women, meaning that data and indicators of impact need to include gender, especially in the context of Africa.

IIASA Energy Researcher Pachauri reflected on the inequalities that we see in our everyday lives. Her work specializes in household energy access in the developing world. Pachauri shared an example from an organization called ENERGIA, of which she is a member of the advisory board, where women were included as microentrepreneurs in the delivery of energy in villages. The organization found that female entrepreneurs were more successful and profitable than the men, which they put down to a greater use of social networks and relationships. The example demonstrated how societies can benefit from including women in solutions for everyday problems.

Aboulnasr, a retired electrical engineering professor, focused on the importance of balance – whether it is a balance of genders, social classes, or geography. Aboulnasr eloquently suggested that rather than striving for perfect balance, one should accept a more dynamic and changing balance. She also stated that one should focus on the impact, rather than on the tools. For example, excellent science is a tool for reaching a goal that makes an impact, rather than excellence in science being the goal. Her advice to the audience was to be open to accepting failure in one’s life.

“If you don’t fail in 30% of what you attempt to do, then you have never reached your limits,” she said, and encouraged the audience to stop obsessing about the failures of the past, seek balance, and to not feel guilty.

Scholes, a professor at the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa, approached the question of the day differently. She urged the audience to look at the question from a sustainability perspective, and to ask what role gender has to play in stewardship for the planet. In addition, she asked the audience to consider whether our unstainable use of resources is because of gender inequality, or because of a more underlying misalignment of values, and what type of empowerment might be needed to achieve a more sustainable world.

“As far as we know, this is the first panel discussion hosted at IIASA which has specifically tried to examine the role of women in achieving a sustainable future. We learned that there are pockets of IIASA research already exploring this this issue and that there is room and interest to engage in this discussion in the future,” says Palazzo.

It is clear that there is no simple answer to the issues surrounding the topic of our International Women’s Day panel discussion. The event however, highlighted unique reflections and experiences from each panelist, and the IIASA Women in Science Club will continue to explore and push the discussion forward. We look forward to updating you soon.

Some of of the panel discussion attendees wearing red, purple and black themed clothes for International Women’s Day

Aug 30, 2017 | Environment, Food & Water, Young Scientists

By Parul Tewari, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2017

Two things are distinctly noticeable when you meet Cornelius Hirsch—a cheerful smile that rarely leaves his face and the spark in his eyes as he talks about issues close to his heart. The range is quite broad though—from politics and economics to electronic music.

Cornelius Hirsch

After finishing high school, Hirsch decided to travel and explore the world. This paid off quite well. It was during his travels, encompassing Hong Kong, New Zealand, and California, that Hirsch started taking a keen interest in economic and political systems. This sparked his curiosity and helped him decide that he wanted to take up economics for higher studies. Therefore, after completing his masters in agricultural economics, Hirsch applied for a position as a research associate at the Austrian Institute of Economic Research and enrolled in the PhD-program of the Vienna University of Economics and Business to study trade, globalization, and its impact on rural areas. Currently, he is looking at subsidies and tariffs for farmers and the agricultural sector at a global scale.

As part of the 2017 Young Scientists Summer Program at IIASA, Hirsch is digging a little deeper to analyze how foreign direct investments (FDI) in agricultural land operate. “Since 2000, the number of foreign land acquisitions have been growing—governmental or private players buy a lot of land in different countries to produce crops. I was interested in knowing why there are so many of these hotspots in the world— sub-Saharan Africa, Papua New Guinea, Indonesia—why are people investing in these areas?,” says Hirsch.

Farming in one of the large agricultural areas in Indonesia ©CIFOR I Flickr

Increased food demand from a growing world population is leading to an increased rate of investment in agriculture in regions with large stretches of fertile land. That these regions are largely rain-fed make them even more attractive for investors as they save the cost of expensive irrigation services. In fact, Hirsch argues that “the term land-grabbing is misleading. It should actually be water-grabbing as water is the foremost deciding factor—even more important than simply land abundance.”

Some researchers have found an interesting contrast between FDI in traditional sectors, such as manufacturing, and the ones in agricultural land. While investors in the former look for stable institutions and good governmental efficiency, FDI in land deals seems to target regions with less stable institutions. This positive relationship between corruption and FDI is completely counterintuitive. Hirsch says that one reason could be that “sometimes weaker institutions are easier to get through when it comes to such vast amount of lands. A lot of times these deals and contracts are oral and have no written proof—the contracts are not transparent anyway.”

For example in South Sudan, the land and soil conditions seem to be so good that investors aren’t deterred despite conflicts due to corrupt practices or inefficient government agencies.

One of the indigenous communities in Madagascar, a place which is vulnerable to land acquisitions © IamNotUnique I Flickr

One area that often goes unnoticed is the violation of land rights of indigenous communities. If a government body decides to sell land or give out production licenses to investors for leasing the land without consulting the actual community, it is only much later that the affected community finds out that their land has been given away. Left with no land and hence no source of livelihood, these communities are forced to migrate to urban areas.

A strain of concern enters his voice as Hirsch talks about the impact. “Land as big as two times the area of Ecuador has been sold off in the past—but it accounts for a tiny percentage of the global production area.” With rising incomes and greater consumption of meat, a lot of land is used to produce animal feed crops. “This is a very inefficient way of using land,” he says.

During the summer program at IIASA, Hirsch is generating data that will help him look at these deals in detail and analyze the main factors that are taken into consideration before finalizing a land deal. At the moment he is only able to give an overview of land-grabbing at the global level. With more data on the location of the deals he can look at the factors that influence these decisions in the first place such as the proximity between the two countries involved in agricultural investments and the size of their economies.

While there is always huge media coverage when a scandal about these land acquisitions comes out in the open, Hirsch seems determined to dig deeper and uncover the dynamics involved.

About the researcher

Cornelius Hirsch is a research associate at the Austrian Institute of Economics and Research (WIFO). At IIASA he is working under the supervision of Tamas Krisztin and Linda See in the Ecosystems Services and Management Program (ESM).

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 25, 2017 | IIASA Network, Sustainable Development

Johanna Mair is a professor of Organization, Strategy and Leadership at the Hertie School of Governance, Academic Editor of Stanford Social Innovation Review, Co-Director of the Global Innovation for Impact Lab at the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society, and Academic Co-Director Social Innovation and Change Initiative at the Harvard Kennedy School. Mair is also a member of the Alpbach-Laxenburg Group, which holds its annual retreat this weekend on the sidelines of the European Forum Alpbach.

Johanna Mair ©Hertie School of Governance

At the Alpbach-Laxenburg Group retreat this weekend, you will be joining a discussion on governance and institutional transformation towards sustainability. What do you see as the biggest barriers to sustainable development?

Sustainability challenges typically require a concerted effort to achieve impact. We still lack the appropriate governance and accountability mechanisms that ensure implementation of well-intended strategies and commonly devised goals.

As an expert in social entrepreneurship and innovation, what new developments have you seen that you think could drive a transformation towards sustainability? Could you give examples of successful innovations that have taken hold?

We do see innovation on many fronts. Especially in governance technology has enabled a number of useful and helpful innovations that allow for more transparent and accountable processes. At the same time we still face enormous challenges that cannot be fixed by technology and require us to face deeply rooted relational and cultural problems. The prevalence of open defecation and lack of sanitary infrastructure in India is just one example.

Sometimes it seems like there are many great ideas, but adoption is slow. What do you think is necessary to make the leap from innovative idea to widespread practice?

“Most new ideas are bad ideas” as Jim March from Stanford University would say. We must stop praising innovation and start to think and act on linking innovation and scaling as two distinct process to create impact. Innovation is an investment and creates the potential for impact. Scaling enacts and grows this potential and transforms innovation into tangible outcomes – improving the lives of marginalized people and communities and making progress on stubborn societal and environmental problems.

We have elaborated on this in our new book on “Innovation and Scaling for Impact – How Successful Social Enterprises Do It,” which I co-wrote with Christian Seelos.

How do innovation and governance go together? What are the challenges and opportunities for bringing new ideas into institutions and governments?

Governance needs to exert an enabling role. We need to craft and design governance systems that foster innovation. At the same time, governance systems need also make sure that the potential and usefulness of innovation can be tested along the way. This requires reflecting on markers of success that are process and not outcome focused.

The Alpbach-Laxenburg Group brings together leaders from business, and young entrepreneurs, along with government leaders and science experts. What do you think can be gained from a meeting of this type?

The most important outcome will be a shared understanding of priorities, pathways, and markers of success for this journey.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

More information

IIASA at the European Forum Alpbach 2017 and Alpbach-Laxenburg Group Retreat: 27-29 August 2017

Johanna Mair appearances at Alpbach: 19 August – 1 September

Aug 7, 2017 | Climate Change, Food & Water, Water, Young Scientists

By Parul Tewari, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2017

In 2016, Bolivia saw its worst drought in nearly 30 years. While the city of La Paz faced an acute water shortage with no piped water in some parts, the agricultural sector was hit the hardest. According to The Agricultural Chamber of the East, the region suffered a loss of almost 50% of total produce. Animal carcasses lay scattered in plain sight in the valleys, where they had died looking for watering holes.

Lake Poopo (Bolivia) before it dried up © David Almeida I Flickr

One of the most dramatic results of this catastrophic drought was that Lake Poopo, (pronounced po-po) Bolivia’s second largest lake was drained of every drop of water. Located at a height of approximately 1127 meters, and covering an area of 1,000 square kilometers, what remains of it now resembles a desert more than a lake. This event forced the fishing community of Uru Uru, which depended on the lake, to either migrate to other lakes or look for alternate livelihood options.

Lake Poopo is located in the central South American Altiplano, one of the largest high plateaus in the world (Bolivia’s largest lake, Titicaca, is located in the north of the region). Due to its unique topography, the highland faces extreme climatic conditions, which are responsible for difficult lives as well as widespread poverty among the people who live there.

While Titicaca is over 100 meters deep, Poopo had a depth of less than three meters. Combined with a high rate of evapotranspiration, erratic rainfall, and limited flow of water from the Desaguadero River, Poopo was in a precarious position even during the best of times. Whatever little water flowed in from the river is further depleted by intensive irrigation activities at the south of Lake Titicaca before the water makes it way down to Poopo.

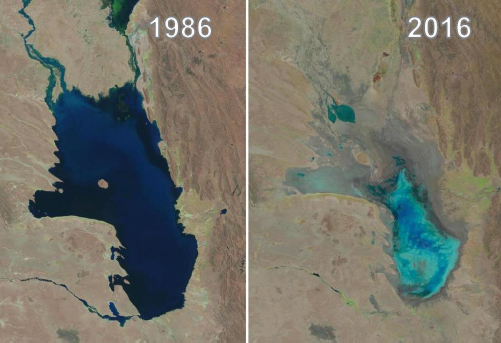

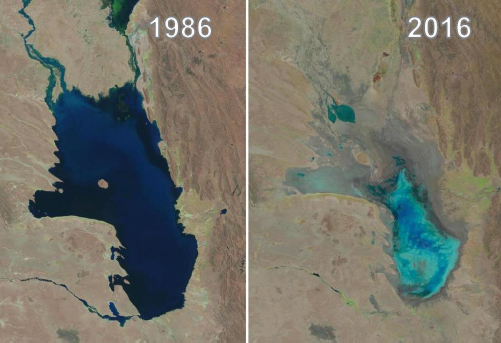

Sattelite images of Lake Poopo

Changes in water levels of Lake Poopo over 30 years © U.S. Geological Survey, Associated Press

The lake’s existence had been threatened several times in the past. However, the 2016 drought was one of the most devastating ones. According to the Defense Ministry of Bolivia, early this year the lake started recovering after several days of heavy rain, restoring as much as 70% of the water. However, since the lake is a part of a very fragile ecosystem, there have been some irreversible changes to the flora and fauna in addition to the losses to the fishing communities living around the lake.

Charting a better future

Claudia Canedo, a participant of the 2017 Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) at IIASA, is exploring the impact of droughts and the risk on agricultural production in the light of this event, after which Bolivia declared a state of water emergency. Canedo was born and raised in the city of La Paz and experienced water shortages while growing up close to the Altiplano. This motivated her to investigate a sustainable solution for water availability in the region. With the results of her study she is hoping to ensure that such a situation doesn’t arise again in the Altiplano – that other communities directly dependent on ecosystem services, like that of Lake Poopo, do not have to lose everything because of an extreme weather event.

For a region where more than half the population is dependent on agriculture for their livelihoods, droughts serve as a major setback to the national economy. “It is not just one factor that led to the drought, though. There were different factors that contributed to the drying up of the lake and also contribute to the agricultural distress,” she says.

“The southern Altiplano lies in an arid zone and receives low precipitation due to its proximity to the Atacama Desert. Poor soil quality (high saline content and lack of nutrients) makes it unsuitable for most crops, except quinoa and potato in some areas,” adds Canedo. Residents also lack the knowledge and the monetary resources to invest in newer technology, which could possibly lead to better water management.

A woman from one of the drought affected communities in Bolivia © EU – Photo credits: EC/ECHO/Laurence Bardon I Flickr

One of the most critical factors in the recent drought was the El Nino- Southern Oscillation, the warming of the sea temperatures in the Pacific Ocean, which in turn carries the warmer oceanic winds and lowers the rate of precipitation in the highland leading to increased evapotranspiration. In 2015 and 2016, the losses due to this phenomenon were devastating for agriculture in the Altiplano, says Canedo.

In her quest to find solutions, the biggest challenge is the lack of recorded data from local weather stations for the past years. Although satellite data is available, it is too generic in nature to do a local analysis. Therefore combining ground and satellite data could enhance the present knowledge and provide consistent results of the climate and vegetation variability. If done successfully, Canedo hopes to identify a correlation between precipitation and vegetation. With this information, she can improve climate forecasting that could help the local people adapt to droughts powerful enough to turn their lives upside down.

With weather forecasts and early warning systems for extreme weather events like droughts, farmers would know what to expect and would be able to plant resilient varieties of crops. This might not earn them the same profits as in a normal year, but would not result in a failed crop. Claudia aims to come up with a drought index useful for drought monitoring and early warning, which will integrate short-term and long-term meteorological predictions.

Perhaps, in the future, with this newfound knowledge, the price for extreme weather events won’t be paid in terms of lost ecosystems like that of Lake Poopo, robbing people of their lives and livelihoods.

About the Researcher

Claudia Canedo is a participant in the 2017 IIASA YSSP. She is pursuing a doctoral program in water resources engineering at Lund University, Sweden. She is interested in studying the hydrological and climatological conditions over small basins in the South American highlands. The aim of her research is to define water resources availability and find strategies for sustainable water management in the semi-arid region.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 23, 2017 | Alumni, Water, Young Scientists

Firdos Khan Yousafzai, PhD student, University of Klagenfurt, Austria, and YSSP 2012 participant

In Pakistan, water supply fell from 5,260 cubic meters per capita in 1951 to 1,050 cubic meters per capita in 2010 according to the World Bank, and is likely to further fall in the future. According to the Falkenmark Water Stress Indicator, a country or a part of a country is said to experience “water stress” when the annual water supplies drop below 1,700 cubic meters per capita per year, and “water scarcity” if the annual water supplies drop below 1,000 cubic meters per capita per year. Water scarcity is especially critical for Pakistan because agriculture contributes 25% of the GDP and 36% of energy is obtained from hydropower.

In terms of geography, Pakistan is incredibly diverse, ranging from plain to desert, hills, forest, and plateaus from the Arabian Sea in the south and to the mountains of Karakorum in the north of the country. It has 796,096 square kilometers area—about the same size as Turkey–and approximately 200 million inhabitants.

The Karakorum mountains in northern Pakistan ©Piotr Snigorski | Shutterstock

Water availability is also different in different parts of the country. While various studies showed that climate change is happening all over Pakistan, research shows that the northern areas are more vulnerable. Possible reasons include the increasing population and deforestation, among others. Therefore, in my PhD work, which was also the subject of my work in the 2012 IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program, I am investigating that how fast climate is changing and exploring its impacts on availability of water.

In a recent study we investigated this issue under four different climate change scenarios, from 2006 to 2039 in the future. Different scenarios have different assumptions about population growth, use of energy type, environmental protection, economic development, technological changes, etc. We calculated the changes on the basis of baseline and future time periods for climate and hydrological projections. We found an increasing trend in maximum and minimum temperature, while precipitation is also changing under each scenario.

To assess water availability and investigate the impacts of changing climate on the operation of reservoirs, we used Tarbela Reservoir as a measurement tool, developing hydrological projections for the reservoir under each scenario. Tarbela Dam is one of the biggest dams in the world, and has a storage capacity of approximately 7 million acre feet and the potential to produce 3,400 megawatts of electricity.

Cholistan Desert in southern Pakistan. Water scarcity varies widely throughout the geographically diverse country. ©image bird | Shutterstock

In our study, we considered all the relevant parameters related to water shortages and surpluses. To compare the status of water availability, we compared the baseline period and future time period. The results show an increasing trend in water availability, however, water scarcity is observed during some months under each scenario. Further, we also observed that there is a 23-40% increase in river flow under the considered scenarios while the average increase is approximately 35% during the future time period.

As a conclusion we can say that enough water is available in Pakistan, and will continue to be available in the future. Instead, the study confirms previous reports that the major problem is mismanagement.

The possible solution may include constructing more dams and storage capacity to store extra water during high river flow which then can be utilized during low river flow. This could probably also be helpful in flood control, raise the groundwater level, and provide cheap and clean electricity to national electricity grid—providing multiple benefits, in view of the fact that the country has faced ongoing energy crises for many years.

References

Ali S, Li D, Congbin F, Khan F (2015). Twenty first century climatic and hydrological changes over Upper Indus Basin of Himalayan region of Pakistan. Environmental Research Letters10 (2015) 014007. DOI:10.1088/1748-9326/10/1/014007.

Khan F, Pilz J, Ali S (2017). Improved hydrological projections and reservoir management in the Upper Indus Basin under the changing climate. Water and Environmental Journal. Vol. 31, No. 2, pp. 235-244. DOI:10.1111/wej.12237.

Khan F, Pilz J, Amjad M, Wiberg D (2015). Climate variability and its impacts on water resources in the Upper Indus Basin under IPCC climate change scenarios. International Journal of Global Warming, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 46-69. DOI:10.1504/IJGW.2015.071583.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.