May 9, 2017 | Alumni, Young Scientists

Former IIASA Director Roger Levien started the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) in the summer of 1977. After 40 years the program remains one of the institute’s most successful initiatives.

The idea for the YSSP came out of your own experience as a summer student at The RAND Corporation during your graduate studies. How did that experience inspire you to start the YSSP?

At RAND I was introduced to systems analysis and to working with colleagues from many different disciplines: mathematics, computer science, foreign policy, and economics. After that summer, I changed from a Master’s in Operations Research to a PhD program in Applied Mathematics and moved from MIT to Harvard, because I knew that I needed a broad doctorate to be a RAND systems analyst.

From that point on, I carried the knowledge that a summer experience at a ripe time in one’s life, as one is choosing their post university career, can be life transforming. It certainly was for me.

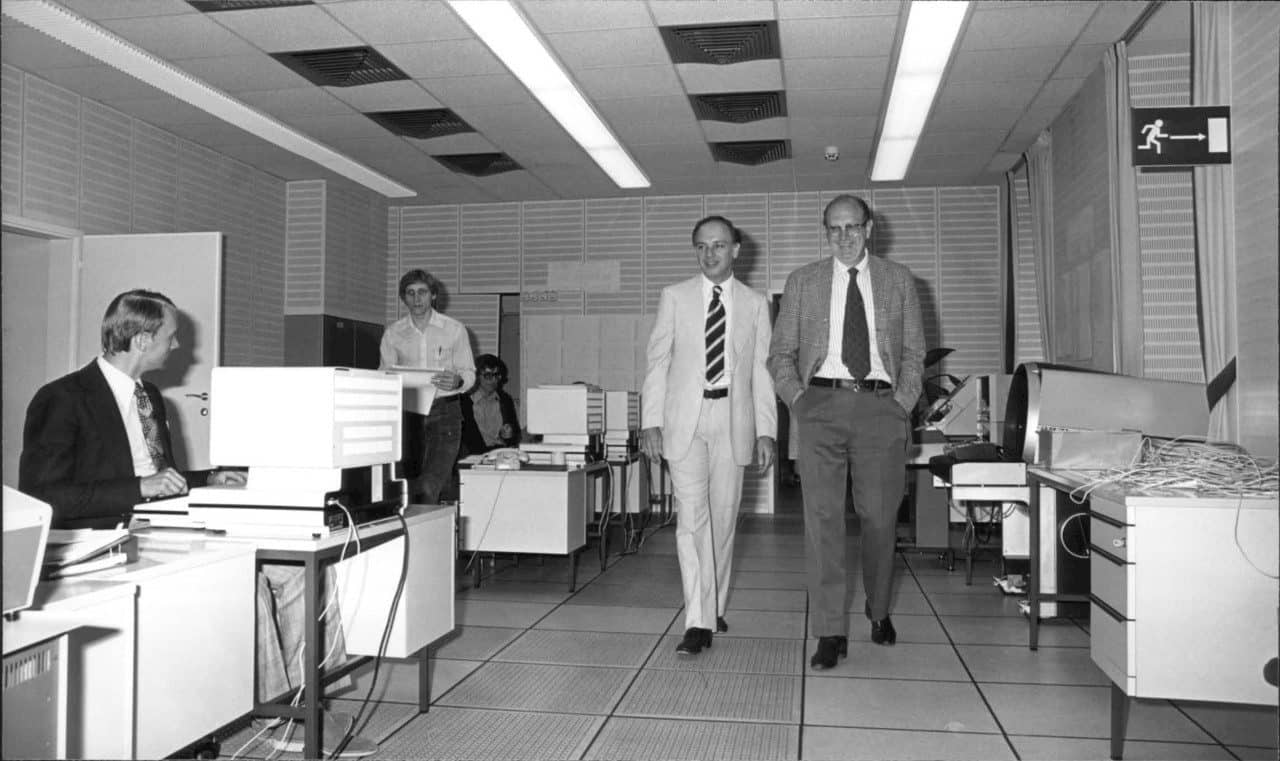

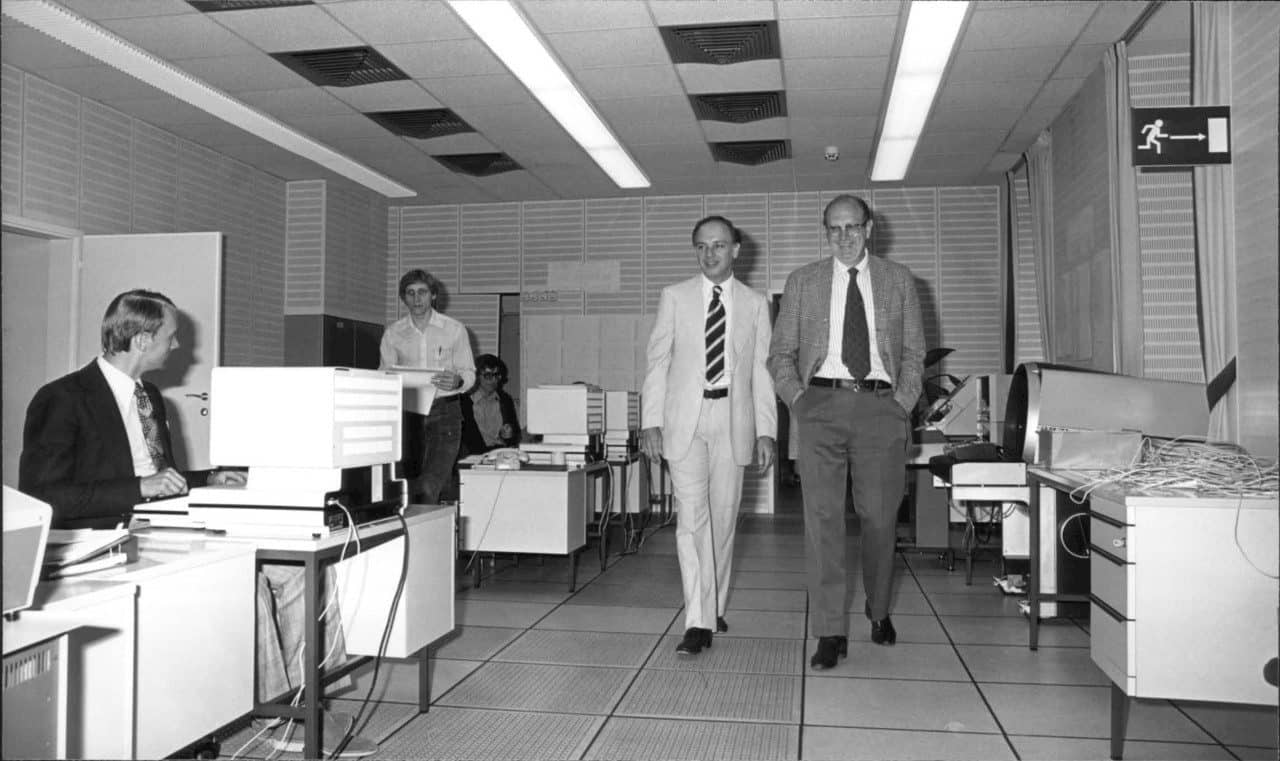

Roger Levien, left, with the first IIASA director Howard Raiffa, right. ©IIASA Archives

Why did you think IIASA would be a good place for such a summer program?

When I thought about such a program within the context of IIASA, it seemed to me that it would offer an even richer experience than mine at RAND. I thought, wouldn’t it be wonderful to bring young scientists from many nations together in their graduate-program years at IIASA. At that time, systems analysis was not well-known anywhere outside of the United States, and even there it was not very well known. In universities interdisciplinary research, and especially applied policy research, was almost nonexistent.

This would be an opportunity to introduce systems analysis to graduate students from around the world, who were otherwise deeply involved in a single discipline. It would be fruitful to bring them together to learn about the uses of scientific analysis to address policy issues, and about working both across disciplines and across nationalities.

What was your vision for the program?

I hoped that these students, who had been introduced to systems analysis at IIASA, would become an international network of analysts sharing a common understanding of international policy problems. And in the future, at international negotiations on issues of public policy, sitting behind the diplomats around the table would be technical experts, many of whom had been graduate students at IIASA, having worked on the same issue in a non-political international and interdisciplinary setting. At IIASA they would have developed a common language, a common way of thought, and perhaps working together at the negotiation they could use their shared view to help their seniors achieve success. A pipe dream perhaps, but also an ideal and a vision of what people from different countries and different disciplines who had studied the same problem with an international system analysis approach could accomplish.

Social activities have been an important component of the YSSP since the beginning ©IIASA Archives

The program is celebrating its 40th year. Why do you think it has been so successful?

I think there are many reasons for success. But for one thing, it’s my impression that just having 50 enthusiastic young scientists around brings an infusion of energy, which is a great boost to the institute. The young scientists also bring findings and methods on the cutting edges of their disciplines to IIASA.

What would be your advice to young scientists coming this summer for the 2017 program

It would be to engage as deeply as you can and as broadly as you can. This is an opportunity to learn about many things that aren’t on the curriculum of any university program. So, now’s the time to engage not only with other disciplines, but with people from other nations, to get their perspective. The people you meet this summer can be lifelong contacts. They can be your friends for life, your colleagues for life, and the opportunities that will open through them, though unpredictable, are bound to be invaluable, both professionally and personally.

This is a learning experience of an entirely different type from the typical graduate program, which goes deeper and deeper into a single discipline. You have a unique opportunity to go broader and wider, culturally, intellectually, and internationally.

IIASA will be celebrating the YSSP 40th Anniversary with an event for alumni on June 20-21, 2017.

This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 23, 2016 | Science and Art, Science and Policy

Gloria Benedikt was born to dance. She started at the age of three and since the age of 12 she has been training every day—applying the laws of physics to the body. But with a degree in government and an interest in current affairs, Benedikt now builds bridges between these fields to make a difference, as IIASA’s first science and art associate.

Conducted and edited by Anneke Brand, IIASA science communication intern 2016.

Gloria Benedikt © Daniel Dömölky Photography

When and how did you start to connect dance to broader societal questions?

The tipping point was when I was working in the library as an undergraduate student at Harvard University. I had to go to the theater for a performance, and thought to myself: I wish I could stay here, because there is more creativity involved in writing a paper than in going on stage executing the choreography of an abstract ballet. I realized that I had to get out of ballet company life and try to create work that establishes the missing link between ballet and the real world.

To follow my academic interest, I could write papers, but I had another language that I could use—dance—and I knew that there is a lot of power in this language. So I started choreographing papers that I wrote and rather than publishing them in journals, I performed them. The first work was called Growth, a duet illustrating how our actions on one side of the world impact the other side. As dancers we need to concentrate and listen to each other, take intelligent risks and not let go. If one of us lets go, we would both fall on our faces.

What motivated you make this career change?

We as contemporary artists have to redefine our roles. In recent decades we became very specialized, which is great, but we lost our connection to society. Now it’s time to bring art back into society, where it can create an impact. I am not a scientist. I don’t know exactly how the data is produced, but I can see the results, make sense of it and connect it to the things that I am specialized in.

How did you get involved with IIASA?

I first started interdisciplinary thinking with the economist Tomáš Sedláček who I met at the European Culture Forum 2013. A year later I had a public debate with Tomáš and the composer Merlijn Twaalfhoven in Vienna. Pavel Kabat, IIASA Director General and CEO, attended this and invited me to come to IIASA.

What have you done at IIASA so far?

For the first year at IIASA I created a variety of works to reach out to scientists and policymakers and with every work I went a step further. This year, for the first time I tried to integrate the two groups by actively involving scientists in the creation process. The result, COURAGE, an interdisciplinary performance debate will premiere at the European Forum Alpbach 2016. In September, I will co-direct a new project called Citizen Artist Incubator at IIASA, for performing artists who aim to apply artistic innovation to real-world problems.

Gloria and Mimmo Miccolis performing Enlightenment 2.0 at the EU-JRC. The piece was specifically created for policymakers. It combined text, dance, and music, and reflected on art, science, climate change, migration and the role of Europe in it. © Ino Lucia

How do scientists react to your work?

The response to my performances at the European Forum Alpbach 2015 and the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (EU-JRC) was extremely positive. It was amazing to see how people reacted—some even in tears. Afterwards they said that they didn’t understand what I was trying to say for the past two days, but the moment that they saw the piece, they got it. Of course people are skeptical at first—if they were not, I will not be able to make a difference.

Gloria and Mimmo Miccolis rehearsing at Festspielhaus St. Pölten for COURAGE which will premiere at the European Forum Alpbach 2016.

What are you trying to achieve?

I’m trying to figure out how to connect the knowledge of art and science so that we can tackle the problems we face more efficiently. There are multiple dimensions to it. One is trying to figure out how we can communicate science better. Can we appeal to reason and emotion at the same time to win over hearts and minds?

As dancers we can physically illustrate scientific findings. For instance, in order to perform certain complicated movements, timing is extremely critical. The same goes for implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Are you planning on doing research of your own?

At the moment I am trying something, evaluating the results, and seeing what can be improved, so in a way that is a type of research. For instance, some preliminary results came from the creation of COURAGE. We found that if we as scientists and artists want to work together, both parties will have to compromise, operate beyond our comfort zones, trust each other, and above all keep our audience at heart. That is exactly what we expect humanity to do when tackling global challenges. We have to be team players. It’s like putting a performance on stage. Everyone has to work together.

More information about Gloria Benedikt:

Benedikt trained at the Vienna state Opera Ballet School, and has a Bachelor’s degree in Liberal Arts from Harvard University, where she also danced for the Jose Mateo Ballet Theater. Her latest works created at IIASA will be performed at the European Forum Alpbach 2016 as well as the International Conference on Sustainable Development in New York.

www.gloriabenedikt.com

Fulfilling the Enlightenment dream: Arts and science complementing each other

Note: This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 19, 2016 | Science and Policy, Young Scientists

By Anneke Brand, IIASA science communication intern 2016.

For Malgorzata (Gosia) Smieszek it’s all about making sound decisions, and she is not afraid of using unconventional routes in doing so. She applies this rule to various aspects of her fast-paced life. Whether it is taking the right steps in trail running races, skiing or relocating to the Arctic Circle to do a PhD.

Gosia Smieszek © J. Westerlund, Arctic Centre

Gosia’s passion for the Arctic began to evolve during a conversation with a professor at a time when she was contemplating the idea of returning to academia. “I remember, when he said the word Arctic, I thought: yes, that’s what I want to do. True, before I was interested in energy and environmental issues, but the Arctic was certainly not on my radar. So I went to the first bookstore I found, asked for anything about the North and the lady, after giving me a very confused look, said she might have some photo books. So I left with one and things developed from there.”

In 2013 Gosia joined the Arctic Centre of the University of Lapland in Rovaniemi, Finland. Living there is not always easy, but hey, if you get to see the Northern Lights, reindeers and Santa Claus on a regular basis, it might be worth enduring long times of darkness in winter and endless sunshine in summer. With temperatures averaging −30°C, Rovaniemi is the perfect playground for Gosia.

Running is one of Gosia’s favorite sports. She has competed in a few marathons, but her biggest race to date is the Butcher’s Run, an ultra trail of 83km over the Bieszczady mountains in Poland. Here she is running in the Tatra mountains. © Gosia Smieszek

Gosia grew up in Gliwice, a town in southern Poland, before moving to Kraków where she completed her undergraduate degree in international relations and political science. This was just before Poland’s accession to the EU, so it was the perfect time to pursue studies in this field.

She continued her studies in various locations including Belgium, France, Poland, and Austria. Before continuing her education and later working at the College of Europe, she also gained working experience as a translator at a large printing house in her home town in Poland.

For her PhD Gosia focuses on the interactions between scientists and policymakers, with the aim of enhancing evidence-based decision making in the Arctic Council. Scientific research on the Arctic has been conducted for decades, but “when it comes to translating science into practice it is still a huge challenge―on all possible levels,” she says.

“Scientists and policymakers have their own, very different, universes—with their own stories, goals, timelines, working methods and standards. It is better than in the past, but still extremely difficult to make these two universes meet.”

Gosia with fellow YSSPers, Dina, Stephanie and Chibulu during a visit to Hallstadt. © Chibulu Luo

As part of the Arctic Futures Initiative at IIASA, Gosia investigates and maps the structural organization of the Arctic Council and aims to determine the effectiveness of interactions between scientists and policymakers, as well as ways to improve the flow of knowledge and information between them.

Because of the nature of her work, Gosia spends almost half her time away from home, but you will never find her traveling without running shoes, swimming gear, and something to read. Diving, one of her greatest passions, has taken her to amazing places like Cuba and the Maldives, where meeting a whale shark face-to-face topped her list of underwater experiences.

Gosia swimming with a whale shark. © Eiko Gramlich

Gosia is truly hoping to make a difference with her research on science-policy interface. She says: “To me, trying to bridge science and policy is a truly fascinating endeavor. Exploring these two worlds, seeking to understand them and learning their ‘languages’ to enable better communication between them is what drives me in my research. So hopefully we can learn from past mistakes and make things better—this time.”

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Mar 1, 2016 | Communication, Science and Policy

By IIASA Science Writer and Editor Daisy Brickhill.

“The thing about communicating science today is…people can always watch cat videos instead. And let’s face it, some of those clips are really funny.”

Marshall Shepherd, former president of the American Meteorological Society, smiles at the audience of this science communication seminar, aware of the frustrated sighs going on in the room, and in some cases the blank incredulity—people wouldn’t watch cat videos when they could be paying attention to my science, surely?

We are at the AAAS annual meeting, a vast conference with around 10,000 attendees from all walks of life, from toddlers to retired professors. The science presented here is truly diverse, and covers everything from radically successful new cancer treatments, to advances in artificial intelligence, to the IIASA session on how we can hope to achieve all 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Shepherd is speaking of his long career engaging with the public about his work on weather systems and climate change. “Get out of your ivory tower,” he urges all researchers. There are important issues at stake, and what if no one speaks for the scientific evidence?

However, communicating science effectively is not easy. Understanding something does not mean you are automatically good at explaining it. All through academic training researchers learn how to speak to people in their own field, who talk just like them. That’s important, they might be your next reviewer, after all. But it is only one, narrow form; engaging the public requires a high level of understanding, not just of the topic, but of the audience and communication itself.

“We have left behind the old idea of science communication where brains are empty vessels waiting to be filled,” says the next speaker, Barbara Klein Pope, executive director for communications for the National Academies. “They are a swamp, and we need to explore that swamp to communicate properly.” She describes research which tested the effects of different types of communication on people’s perceptions of social science, in terms of whether they felt it was worth funding, for instance (oh yes, I sense the academic ears pricking up now).

The mind is not an empty vessel waiting to be filled, it’s a swamp to be navigated.

The findings of this work led to a framework of three clear messages. First, use exemplars—a good example can do wonders—yes, your research might be relevant across reams of different cases but general, expansive terms are often vague and a simple example can bring clarity.

Second, the all-important yet surprisingly often neglected question, “Why do we care?” Bear in mind also that it’s not why you care, you’ve made a career out of this science, we know why you care, but why should your audience care.

Finally, use metaphors. Science is often very complex, and pretty much anyone outside your field will need something they can relate to—a familiar concept that they can use to begin to explore the new territory. In case you need more convincing, the use of metaphors was shown to have a significant effect on whether the public felt the work was worth funding.

At the end of that session I was struck by the parallels between this session and another I attended on science-policy interactions with speakers Vladimír Sucha, Daniel Sarewitz, and Peter Gluckman, all working at the forefront of science-policy.

Trust, built on good communication, is vital, the speakers all agreed. Interesting conclusions should not be buried at the end of a report, they should be at the start, just as they would be for the public, and any article or briefing should be kept as short and relevant as possible. Examples and metaphors play a role here too, and a good story with persuasive anecdotes can have much more impact than a dry report.

What not to do, Sucha reminds us, is send an email saying “Here are the links to 200 peer-reviewed papers on this, you’ll find it all there.” After all, policymakers can access cat videos just as easily as the rest of us.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 27, 2015 | Science and Policy

By Tanja Kähkönen, University of Eastern Finland, School of Forest Sciences & Institute for Natural Resources, Environment and Society

This autumn I attended the first joint JRC-IIASA Summer School on Evidence and Policy, which brought together policymakers and early-career scientists like myself to learn about the evidence-policy interface. After intensive days of interacting at lectures, learning together, and sharing views during the breaks, I can really say that as scientists we are operating in a different culture to policymakers.

Discussion and debate fostering greater understanding between researchers and policymakers at the JRC-IIASA summer school

This difference extends not only to what we do in our daily work, but also to what kind of language we use, how we communicate, and what level of certainty we give—or have to give—to the issues that we address. Often as scientists we are so intensively involved in our own work that we forget that communicating our research to policymakers cannot be done in the same way as communication with other researchers. This is because policymakers have different evidence needs, expected timeframes for information production, and level of discipline-specific understanding.

However, despite the different cultures, it is possible to learn to speak each others’ language and communicate more efficiently. Developing this communication was practiced throughout the course and a significant part of this took place during “masterclasses,” given by people who are themselves at the science-policy interface as part of their daily work.

I found the masterclass session on wicked problems and evidence-based policy, run by Jan Staman and Annick de Vries from the Rathenau Institute in the Netherlands, particularly attention-grabbing. They pointed out that apart from crises, for which policymakers need rapid evidence on specific topics, wicked—difficult to solve—problems such as creating climate change policy may face problems of scientific evidence overload, political dead-locks, and societal controversies.

The masterclass on uncertainty, risk and hazard, and the links to policymaking was also particularly eye-opening. Session leaders David Wilkinson and Jutta Thielen of the JRC suggested that a range of scenarios and consequences should be offered to policymakers in order to allow them to take better decisions under uncertain conditions in which risks of human loss or health hazard maybe high.

Other sessions focused on foresight, effective communication, using games for informing public and policy debates (crowdsourcing our search for solutions), big data, randomization, modeling, and the pros and cons of working at the science-policy interface—all very important topics for improving communication between scientists and policymakers.

All in all, I guess the take home messages of this course are different for each participant. As a scientist, the big messages for me came from the wrap up session in which “dos and don’ts” for evidence-informed policymaking were summarized by all the summer school participants. For the “dos” words such as trust, communication, providing clear and concise messages, being certain about something, keeping it simple, and understanding policy processes leapt out at me.

Despite the fact that the summer school lasted only three days, I am positive that it will have a lasting effect on the participants, opening a path for cross-cultural understanding between scientists and policymakers. Together improving communication to the benefit of our changing society.

Participants of the first JRC-IIASA Summer School on Evidence and Policy

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.