Mar 11, 2016 | Demography

By Luis Castro, researcher in the Sustainability NEXUS Research Cluster of the IIASA World Population Program.

The refugee crisis going on across Europe has brought the importance of migration analysis into sharp focus. Policymakers need to know the answers to many questions that require realistic and timely answers, such as:

- What are the demographic impacts of massive immigration in the short, medium, and long term?

- What are the impacts on a population’s age distribution if the immigrants are migrating as family units, especially if they have a cultural tradition of large numbers of children?

- What are the impacts if the immigrants are mainly males of labor-force age?

- Is there a relationship between education level and the propensity to migrate?

For almost 40 years, IIASA has developed analytical tools and system analysis methods to help answer these questions and others. These methods and tools have been used for UN population projections, as well as by many individual countries around the world, but there is still much research to be done on to help us understand the complex dynamics of migration.

Until the end of the last century, migration modeling was given scant attention. A simple explanation for such lack of interest is perhaps the fact that most social, economic, and demographic research was targeted at the national level. Under such circumstances it was generally assumed that populations were “closed” and international migration was not considered. In addition, demographic studies of sub-national areas used the measure of “net migration”—the number of immigrants minus the number of emigrants—even though this simplifies the situation to the point where key information is lost.

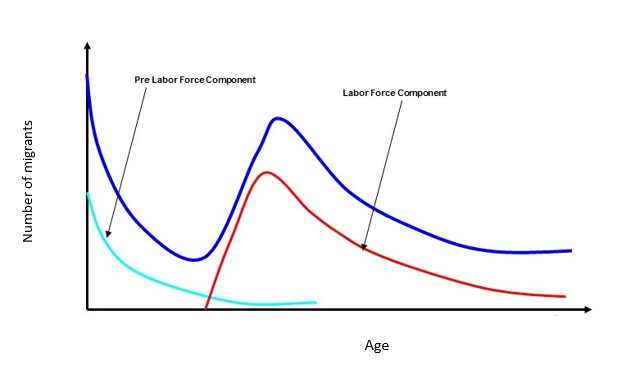

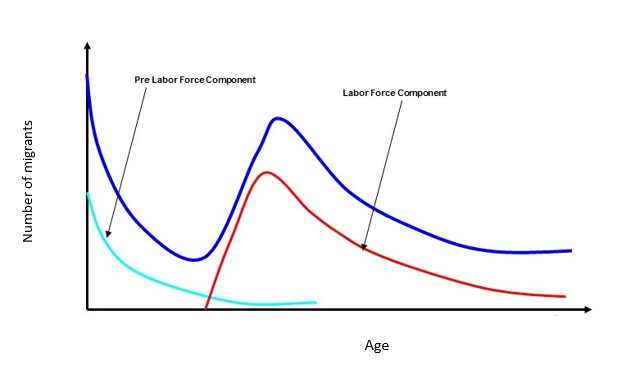

In 1977, just after IIASA had completed its first five years of research activity, the institute announced that a key research theme for the future would be human settlements and services. This focused on developing methods for multiregional demography and included analysis and modeling of age specific migration flows was using data from 17 IIASA national member countries as well as Mexico, which was not yet a member. I dedicated five years at IIASA to developing and testing different migration models investigating patterns of age distributions among groups of migrants, see the graph.

This graph shows how the numbers of migrants of different ages vary. Families migrating, for example, cause a peak in numbers at pre-labor force ages.

Demographic studies often view migration as a collection of independent individual movements. Yet it is widely recognized that many migrations undertaken by individuals whose movements are linked to others. For example, children migrating with their parents, wives with their husbands, or grandparents with their grandchildren.

The aim of my early research at IIASA was to identify some of the effects of family dependency on the migration of men and women, and those of different ages. We developed a model that split migration into independent and dependent flows. This work can explain variations in patterns of migration in societies at different stages of development.

The world has drastically changed since the past 25 years or so, and most nations have become more open and dependent on other countries, more regional alliances have appeared. However, international migration will continue to have the utmost priority for policymakers, not only because of the impacts on the receiving countries but also because of the consequences for the countries of origin.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 18, 2016 | Demography

In the 21st century the major global divide runs between knowledge societies and those where access to education is hampered or denied, say population experts Reiner Klingholz and Wolfgang Lutz in a new book. In an interview with campus.de they explain what this means.

Education empowers us to look beyond our own horizon and to consciously choose our lifestyle. Better qualified people are more involved in political decision making processes and foster democratization – this is what your book says. Does this mean in reverse that societies with limited education opportunities are, as a rule, less democratic?

Rainer Klingholz: From antiquity to medieval times, the uneducated masses were dominated by despotic elites. Wherever the first seeds of democracy were observed, for example in ancient Greece or Florence during the Renaissance, at least a certain part of the male population could write and read. They were in a better position to see what was going on and they strived for more influence in decision making. The more educated the population became, the more chance there was for democracy. In the modern world, we see a clear statistical association between the education of broad segments of society and a well-functioning democracy, although education is a precondition and not always a guarantee.

There are direct and indirect reasons why education is good for democracy. Education directly fosters the ability to obtain information, express one’s own opinions, engage oneself in discussions and look for compromise, all prerequisites for a lively democracy. Education works indirectly through economic development as it fosters prosperity, and such societies are in a better position to afford the ‘luxury’ of democracy. Even autocratically governed countries, such as Singapore and China, which have invested massively in education and achieved rapid economic growth, can also be seen as moving in the direction of democracy in a long term.

Singapore (home of the aquarium pictured here) and other Asian countries have invested heavily in education, with impressive results. © Goinyk Volodymyr | Dreamstime.com

You say that in a context of global competition countries with low educational standards have lower chances to succeed. Could these countries get out of misery by their own strength or does this problem require a global solution?

Wolfgang Lutz: Looking back in history, we see that many countries have made it without outside assistance. In our book we describe the example of Finland, which was one of the poorest regions of Europe before 1900 and later due to massive educational efforts became not only a winner of PISA test but also one of the most innovative industrial countries. Or, let’s look at Mauritius, which as recently as the 1960s presented a textbook example of a country trapped in the vicious cycle of poverty, population growth, and destruction of the environment. Today, thanks to an early boost in education that was followed by fertility decline and economic growth, it is the most successful country in Africa. Similarly, the rise of the “Asian Tigers” has been induced by massive investment of their own modest means into basic education of the broad layers of population.

In many other countries, mostly in Africa and in South and West Asia, this did not happen. As a consequence, there is still widespread poverty and birth rates have remained high, causing continued rapid population growth and difficulties in finding solutions for existing problems. Under these circumstances, it is not surprising that dissatisfaction results in conflicts which in turn trigger streams of refugees. There are of cause many other reasons for this but lack of education is a root cause.

The most important factor behind decreasing fertility rates is female education. If women complete at least secondary school, they have substantially fewer children, they and their offspring are much healthier, and they become more independent from their husbands, as they are better informed and can obtain their own income. Education is the best and most effective development aid. In order to make this happen, the least developed countries need urgent help from outside. The world cannot wait decades for these countries to later possibly make it on their own. By that time, their population may have multiplied by a factor of 3-5, resulting in higher poverty and possible conflicts. There is good reason why there has been compulsory education and a right to education for all children until the age of 16 for a long time in all developed countries. This must apply equally to all children of the world.

Just a small portion of total development aid expenditures goes into education. Have we still not recognized the problem?

Reiner Klingholz: We have, on paper. The new Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations postulate exactly this. The problem is that these ambitious education goals are not being implemented. Only 2 to 4 percent of global development aid goes into basic education; this makes it impossible for all children to complete primary school and even less secondary school. Most of the development money goes into big infrastructure projects that satisfy local potentates and promote corruption and exports from the donor countries. Building of a rural school, or education of teachers, in Mali or Pakistan are not attractive in that sense. Since educational efforts only become noticeable in 10-20 years, it is much more attractive for a current president to build a new highway. Despite or perhaps because of this, we point out that investment in basic education is the most important investment for enhancing the ability of people and countries to help themselves and it therefore should become an absolute priority in international development.

In some Arab or African countries there is a youth bulge without adequate occupation or place in the society. What are the long-term consequences of this?

Wolfgang Lutz: The main problem of these countries is that the population grows faster than opportunities are being created, especially job opportunities. Many young people do not see prospects for their lives and at the same time they see through TV or internet that elsewhere people are much better off. Under such conditions, young men in particular have a tendency to become radicalized, or fall victim to religious zealots, who tell that people of different religions are the enemies. This mixture leads to a clash between education cultures that we describe in the book.

Students outside a school in Rwanda © Alangignoux | Dreamstime.com

Who or what impedes education in countries like Pakistan, Egypt, or in Western Africa?

Rainer Klingholz: Until the middle of 20th century, most of those countries were pawns in the hands of colonial powers that did not invest in broad education. They were afraid of a population empowered through mass education. In the majority of these countries with independence, authoritarian governments came to power who pursued the same goal: they wanted to stay in power surrounded by small educated elites and had no intention of empowering their citizens through education. Fortunately, in many of the countries the situation has improved in recent years and younger generations are now better educated than the older ones. But there is a real threat from fundamentalist religious or terroristic groups, such as IS or Boko Haram, that actively fight against modern education. They want to stop the teaching of natural sciences and instead have boys memorize the holy scriptures and exclude the girls from education altogether

What does Martin Luther have to do with your book?

Wolfgang Lutz: Martin Luther was the first person in history who actively and successfully fought for the basic education of all, including girls and the poorest farmers. He wanted every individual to find his/her own way to salvation through being able to read the Bible. To achieve this, Luther had to translate the Bible into a language that people understood. But most of all, he had to do something to enable all people to read themselves. This focus on universal literacy was new in world history and went further than e.g. the rather elitist humanists had gone.

Interestingly, we see today that the protestant countries that first implemented those educational reforms in the course of the next decades and centuries became more economically successful as a consequence. The rise of the Netherlands and Great Britain, the industrial revolution, and the later success of the United States, the improvement of living conditions and declining death rates—all this had as a necessary precondition the education of broad segments of the population that ultimately goes back to the Reformation. Luther himself did not have long-term social and economic consequences in mind. Coming from a medieval culture he personally would have been probably unsettled by the following developments towards modernity.

In your book “Who survives?” you describe different scenarios of the future of humanity to the end of the 21st century depending on investments in education in the near future. Can we only survive current and future crises if we indeed prioritize education?

Rainer Klingholz: At the beginning of the 21st century, humanity faces the biggest challenges in its history. It has to abolish poverty, stop population growth, combat climate change, and sustain peace in a world which at the moment may seem to be falling apart. These problems require the best possible brain power and the empowerment through education of everybody. The alternatives to education are high population growth in the poor countries where uneducated women have much higher birth rates together with many other development problems, which likely result in chaos and possibly conflict.

Wolfgang Lutz: The problem is that education needs time to show its positive effects. We have to wait until children come out of school and become active adults. Education is hence not a quick solution to any of the urgent problems that fill today’s newspapers. But in a long run, there are no alternatives to universal education.

Note: This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Dec 15, 2015 | Demography

By Raya Muttarak, IIASA World Population Program

This blog was previously posted on the GMR’s World Education Blog

Not only have climate scientists agreed that humans are contributing to climate change, but recent evidence also points out that the rate of warming is happening much faster now than it ever has before. This is why, at the UN Climate Conference in Paris this month, world leaders sought to reach a new international agreement on climate change, essentially to keep global warming below 2°C (or 3.6°F). Rising temperatures pose threats on food and water security, infrastructure, ecosystems and health and, as a previous blog on this site shows, increases the risk of conflict. With an upsurge in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events and the potential for rapid sea level rise, both mitigating human-related exacerbation of climate change, and adapting to its devastating effects are key priorities. This is where education comes in.

Both mitigation and adaptation require technological, institutional and behavioral responses. Correspondingly, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change highlighted the value of a mix of strategies to protect the planet, which combine policies with incentive-based approaches encompassing all actors from the individual citizen, to national governments and international communities. Because, while national and sub-national climate action plans are fundamental, changing individual behaviour also lies at the heart of responses to climate change.

At the individual level, barriers to the adoption of mitigation and adaptation measures include a lack of awareness and understanding of climate change risk, doubt about efficacy of one’s action, lack of knowledge on how to change behavior and lack of financial resources to implement changes. Accordingly, there are many sound reasons to assume that different education strategies can help overcome these barriers both in direct and indirect manners.

First, directly formal schooling is a primary way individuals acquire knowledge, skills, and competencies that can influence their mitigation practices and adaptation efforts. Schooling provides a unique environment to engage in cognitive activities such as learning to read, write, and use numbers.

Students in Indonesia learn about living with nature. Credit: Nur’aini Yuwanita Wakan/EFAReport UNESCO

As students move to higher grades, cognitive skills required in school become more progressively demanding and involve meta-cognitive skills such as categorization, logical deduction and cause and effect. This abstract cognitive exercise alters the way educated individuals think, reason, and solve problems. Indeed, experimental studies have shown that higher-order cognition improves risk assessment and decision making. These are relevant components of reasoning related to risk perception and making choices about mitigation and adaptation actions.

Furthermore, education enhances the acquisition of knowledge, values and priorities as well as the capacity to plan for the future and allocate resources efficiently. Schooling can help individuals adopt, for instance, disaster preparedness measures by improving their knowledge of the relationship between preparedness and disaster risk reduction. Moreover, educated individuals may have better understanding of what measures to undertake. Recent evidence also shows that education can change time preferences such that more educated people are more patient, more goal-oriented and thus make more investments (e.g., financial, health or education investments) for their future. Such forward-looking attitudes can influence adoption of mitigation actions or adaptation measures where benefits may only be expected by future generations.

Apart from the direct impacts, education may indirectly reduce vulnerability or promote mitigation actions through other means. Firstly, education improves socio-economic status as education generally increases earnings. This allows individuals to have command over resources such as purchasing costly disaster insurance, living in low risk areas and quality housing, installing renewable energy sources at home or being willing to pay carbon taxes.

Secondly, many empirical studies have shown that people with more years of education have access to more sources and types of information. The level of education is not only highly correlated with access to weather forecasts and warnings but the more educated are better able to understand complex environmental issues such as climate change than less educated counterparts.

Knowing where to get information on how to reduce emissions or what adaptations to take allows individuals to change their behaviour appropriately. Indeed, there is evidence that good understanding of climate change or environmental knowledge are associated with climate change mitigation behaviours such as consumption of climate-friendly food, owning fuel-efficient vehicles and conservation behaviour.

In addition, more educated individuals also have higher social capital. A perception of risk and motivations to take preventive action are more likely to be communicated via social networks and through social activities. Evidently, through increasing socio-economic resources, facilitating access to information and enhancing social capital, education can promote and foster sustainable lifestyle and consumption.

Despite these potential benefits on climate action, education has not yet been sufficiently prioritized as a fundamental instrument to fight climate change. Recently researchers at the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital based in Vienna have produced convincing empirical evidence that education, particularly (at least) secondary school, is important for reducing vulnerability to climate change. By showing that education enhances disaster responses, reduces loss and damage and facilitates recovery after disasters, it was argued that part of Green Climate Fund should be spent to promote universal secondary education.

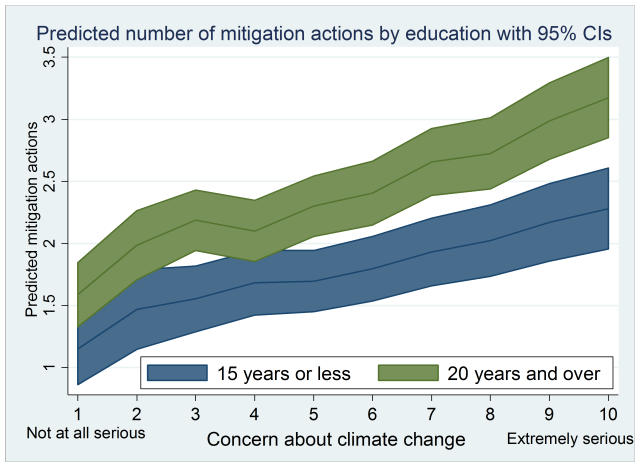

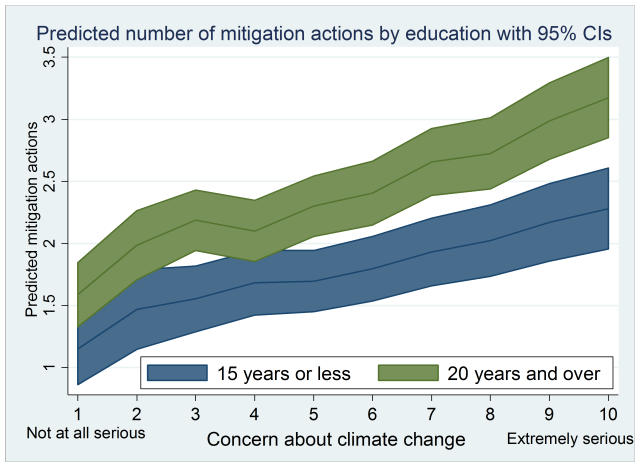

Likewise, education has also been shown to be an important determinant of sustainable lifestyle and consumption. As another blog on this site has shown recently, individuals with a higher level of education are more likely to be concerned about climate change and consequently more likely to take actions to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The Figure below clearly demonstrates how the number of mitigation actions increases with years of schooling. Not only do the highly educated carry out more mitigating actions, education also interacts with concern about climate change. In other words, given the same level of concern about climate change, the highly educated are doing even more to reduce GHG emissions than those with lower education.

Figure 1: Number of mitigation actions taken by years of schooling and concern about climate change

Notes: Own calculation. Estimated from multilevel models with country random effects. Source: Pooled Eurobarometer Surveys (2008, 2009, 2011, 2013).

Responding to the challenges of climate change is going to require action on multiple fronts. Ignoring the impacts of education on climate change is no longer an option. Promoting universal secondary education should be given a high priority on the agenda as we look forward past last week’s Paris meeting.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 10, 2015 | Demography, Young Scientists

By Anne Goujon, IIASA World Population Program

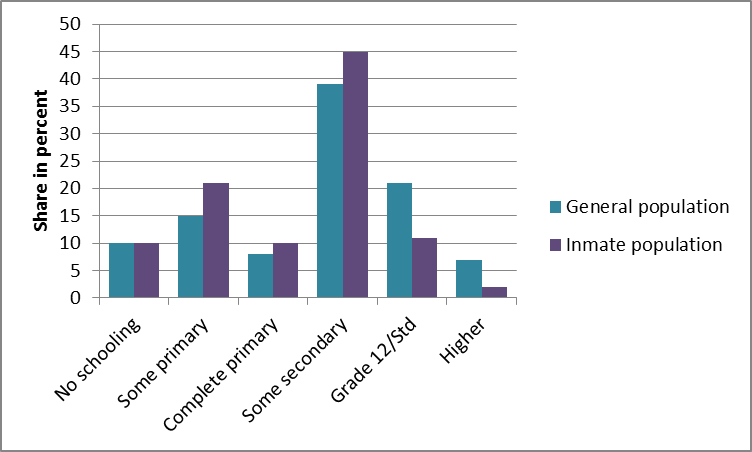

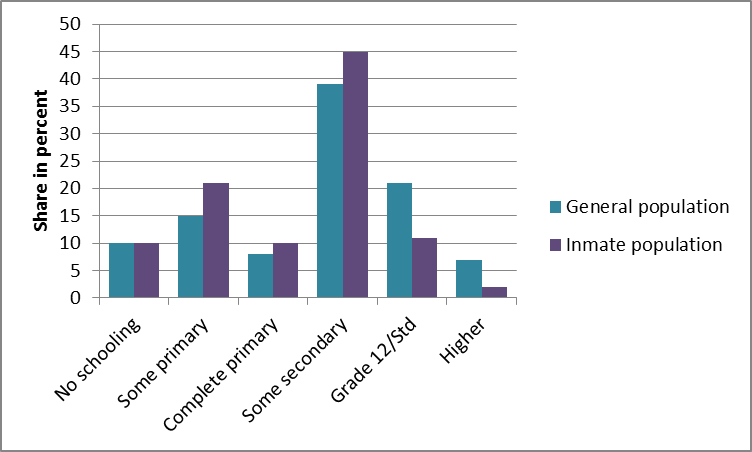

If you live in South Africa and did not complete high school then your chances of committing crime, being caught, and sent to jail are pretty high. This is what we can tell from comparing the education characteristics of the population of inmates in South Africa with that of the population who was not in jail. A recent study that I conducted with a team of African and European researchers in the framework of the Southern African Young Scientists Summer Program confirms some findings from previous research, such as this 2010 study that found that education has a statistically significant effect on crime.

South Africa spends about 8 billion dollars a year on public order and safety. Violence and related injuries are the second primary cause of death in South Africa, and in the last 10 years, the prison population rate has been in a range from 300 to 400 per 100,000 people, one of the highest rates in the world.

© straystone | Dollar Photo Club

South Africa is still plagued with the after-effects of its apartheid history, which enforced sub-standard education for different racial groups, creating a polarized society. The disparity in education between white and other racial clusters actually widened after the fall of the apartheid government. At the same time—and not unrelatedly, as shown by our study—the apparently peaceful transition to a democratic regime was accompanied by a rise of crime and violence, a gauge of the dichotomized South African society and its high levels of social exclusion and marginalization.

Indeed, our analysis of the 2001 census shows that the effect of education on criminal engagement – meaning in this study actually serving time in prison for a crime – differs by race. This suggests that there is an interaction effect between race and education. The negative relationship between being highly educated and the likelihood of being incarcerated is linear for respondents of mixed ethnic origin (or “colored” according to the South African classification), Indians, and to a lesser extent also for Africans. For white respondents, however, the effect of education creates a bell-shaped graph, with the richest and poorest people less likely to be in prison, and the medium levels of education associated with the highest probability to be in prison.

Share of the general and inmate population by level of educational attainment, South Africa, 2001

We also looked at the empirical results from a sample drawn in the Free State province—a crime hot spot – which indicated that a person’s native language, a proxy for race and place of origin, has a statistically significant influence on the likelihood to commit a contact . We also found that the probability of committing contact crimes, including vandalism, threat, assault, and injury, decreased with years of education, while the likelihood of committing economic crimes, including tax fraud, increases with years of education

This research provides another good incentive to invest in education in South Africa, and particularly to insist on all children completing upper secondary education finishing with grade 12. Education statistically significantly decreases the probability of engaging in criminal activity. Hence, it should be included in the National Crime Prevention Strategy, particularly in some targeted provinces within South Africa.

Reference

Jonck, Petronella, Anne Goujon, Maria Rita Testa, John Kandala, 2015, Education and crime engagement in South Africa: A national and provincial perspective. International Journal of Educational Development, 45: 141–151. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.10.002. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0738059315001248

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 20, 2015 | Demography

By Samir KC, IIASA World Population Program (Originally published on the Globalist)

Africa is rising fast, at least demographically. Today, the continent is home to more than a billion people, of which some 950 million of them living in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The UN, for its part, predicts that the continent’s population will double by 2050 — and then double again by the end of this century, to make it a continent of more than 4 billion.

This staggering number – equal to the entire world population as recently as 1980 — may concern many doomsayers, but in reality it contains a lot of good news.

One main reason for the increase is that better living conditions reduce child mortality and create opportunities for longer and healthier lives.

This crucial shift results in a rapidly rising number of adults who are driving the continent’s demographic future.

That development is similar to what occurred in Asia over the last 30 years, which in turn had previously occurred in the Western world.

Barry Aliman, 24 years old, bicycles with her baby to fetch water for her family, Sorobouly village near Boromo, Burkina Faso. Photo by Ollivier Girard for Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR).

UN’s optimistic projections

However, as Wolfgang Fengler and I highlighted recently, in contrast to the UN Population Division’s projections, it is far from certain that Africa will even reach a population totaling 3 billion, and the world 10 billion, by the end of this century.

According to our projections at the Wittgenstein Center, projecting population by age, sex, and educational attainment for almost all countries of the World, Africa’s population may only rise to some 2.6 billion by 2100. That number is only 60% of the 4.4 billion predicted by the UN.

The differences are stark across the biggest African countries. In some countries’ cases, the UN’s forecast is much higher – in fact, even more than double (e.g. Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, Niger, Angola and Mozambique, See table).

Data: UN Population Division and The Wittgenstein Center

How is it possible to have such sharp differences in population projections, which are generally known for their accuracy?

The rate of Africa’s future population growth will mostly depend on two factors. First, the number of children per woman and, second, the chance of those children to survive (which is now much higher, thanks to improving living conditions).

Decline in fertility rate

In any projection far into the future, even a small difference in the number of children per woman makes a big difference in total population numbers when its effect is viewed cumulatively over several generations.

At the core of the two vastly different forecasts is this: The UN assumes that fertility will only decline slowly to 3 children per woman by 2050 — and then 2.6 children by 2070.

These projections are based on the observation that, while fertility has stagnated in parts of Africa in the last decade, it will decline more slowly than it had been declining in other parts of the world.

In contrast, the Wittgenstein Center assumes that the patterns that we will come to observe in Africa are not going to be much different from the case in the other regions of the world, as they went through their demographic transitions.

Once countries urbanize and citizens become wealthier, fertility declines, everywhere.

The most important factor is women’s education. Already today, an Ethiopian woman with secondary education has on average only 1.6 children, compared to a woman with no education who has 6 children.

This relationship is true across Africa (see figure).

Source: Demographic and Health Surveys

Similar trend in Asia

We know that access to education is expanding across Africa. There is even talk of an education dividend.

Once all girls go to school and stay there longer, they will have fewer children, especially as they will also be exposed to a more modern lifestyle, be it through TV, the cell phone and the fact that Africa is urbanizing rapidly.

This has also been the experience in Asia. It took about 20 years in Asia for its fertility to decline from more than 5 children per woman during early 1970s to less than 3 children per woman in early 1990s.

Similarly, India took about 20 years for its fertility to decline from 4.7 children per woman in early 1980s to 3.1 by early 2000s.

With new development and the plans for the better future in the making, it won’t be a surprise if the average African family would have only three children as soon as 2035.

If that assumption bears out, then Africa cannot reach 4 billion — and the world would peak this century at below 10 billion.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.