Jul 22, 2019 | Air Pollution, China, India, Women in Science

By Shonali Pachauri, Senior Researcher in the IIASA Energy Program

Shonali Pachauri explains why data, indicators, and monitoring at finer scales are important to ensure that everyone benefits from policies and efforts aimed at achieving national and global development goals.

A world where no one is left behind by 2030, is the promise nations have made by adopting the United Nations’ Agenda for Sustainable Development. But how does one ensure that no one is left behind? It requires designing inclusive policies and programs that target the most vulnerable and marginalized regions and populations. Sound data and indicators underpin our current understanding of the status of development and are an important part of periodic reviews to determine the direction and pace of progress towards achieving agreed goals. These form the basis of informed decisions and evidence-based policymaking. While an exhaustive list of indicators has been prescribed to monitor progress towards the globally agreed goals, these have been largely defined at a national scale. These goals rely overwhelmingly on simple averages and aggregates that mask underlying variations and distributions.

Indian woman walking home with fire wood © Devy | Dreamstime.com

Recent work I’ve been involved in makes the pitfalls of working with averages and aggregates alone abundantly clear. They can obscure uneven patterns of changes and impacts across regions and groups within the same nation. The overall conclusion of this work is that, even if the globally agreed goals are met by 2030, this is no guarantee that everyone will benefit from their achievement.

A recent Nature Energy – News & Views piece I was invited to write reports on a study that assessed the impacts of China’s recent coal to electricity program across villages in the Beijing municipal region. The program subsidizes electricity and electric heat pumps and has been rolling out a ban on coal use for household heating. The study found that the benefits of the program to home comfort, air quality, and wellbeing varied significantly across rich and poor districts. In poor districts, the study found that the ban was not effective as poor households were still unable to afford the more expensive electric heating and were continuing to rely on coal. Studies such as this one that help us understand how and why benefits of a program may vary across regions or population groups can aid policy- and decision makers in formulating more fair and inclusive policies.

In other recent research carried out with colleagues in the IIASA Energy Program, the Future Energy Program at the Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei (FEEM) in Italy, and the Institute for Integrated Energy Systems at the University of Victoria, Canada, we developed a detailed satellite nightlights derived dataset to track progress with providing electricity access at a sub-national level in Africa. We found that while progress with electrification between 2014 and 2018 varied across nations, at a sub-national provincial level, disparities were even more pronounced. Even more surprising, while electricity access is generally higher and easier to extend in urban areas, we found urban pockets where access has stagnated or even worsened. This correlated with areas where in-migration of populations had been high. These areas likely include urban slums or peri-urban regions where expanding electricity access continues to be challenging. Furthermore, our analysis shows that even where access has been extended, there are regions where electricity use remains extremely low, which means that people are not really benefitting from the services electricity can provide.

In a final example, of research carried out with collaborators from the University of British Columbia and the Stockholm Environment Institute, we evaluated a large nationwide program to promote cooking with liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) in Indian households to induce a shift away from the use of polluting solid fuels. While this program specifically targets poor and deprived, largely rural households, our assessment found that although there has been an unprecedented increase in enrollments of new LPG customers under the program, this has not been matched by an equal increase in LPG sales. In fact, we found consumption of LPG by program beneficiaries was about half that of the average rural consumer. Moreover, when we examined how purchases were distributed across all new consumers, we found that about 35% of program beneficiaries purchased no refills during the first year and only 7% bought enough to substitute half or more of their total cooking energy needs with LPG. Clearly, the health and welfare benefits of a transition to cleaner cooking are still to be realized for most people covered by this program.

Analyses, such as the examples I’ve discussed here, clearly highlight that we need data, indicators, and monitoring at much finer scales to really assess if all regions and populations are benefitting from policies and efforts to achieve national and globally agreed development goals. Relying on aggregates and averages alone may paint a picture that hides more than it reveals. Thus, without such finer-scale analysis and an understanding of the distributional impacts of policies and programs, we may end up worsening inequalities and leaving many behind.

References:

[1] Pachauri S (2019). Varying impacts of China’s coal ban. Nature Energy 4: 356-357. [pure.iiasa.ac.at/15905]

[2] Falchetta G, Pachauri S, Parkinson S, & Byers E (2019). A high-resolution gridded dataset to assess electrification in sub-Saharan Africa. Scientific Data 6 (1): art. 110. [pure.iiasa.ac.at/15982]

[3] Kar A, Pachauri S, Bailis R, & Zerriffi H (2019). Using sales data to assess cooking gas adoption and the impact of India’s Ujjwala program in rural Karnataka. Nature Energy [pure.iiasa.ac.at/15994]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jun 12, 2019 | Economics, Energy & Climate, Eurasia, Young Scientists

By Dmitry Erokhin, Research Assistant in the IIASA Advanced Systems Analysis Program

Dmitry Erokhin shares his thoughts on the promotion of economic progress and security through energy cooperation, good governance, and connectivity in the digital era.

Nadejda Komendantova and Dmitry Erokhin at the OSCE EEF meeting in Bratislava © Dmitry Erokhin

From 27 to 28 May 2019, Bratislava hosted the Second Preparatory Meeting of the 27th Economic and Environmental Forum of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE EEF) on “Promoting economic progress and security in the OSCE area through energy cooperation, new technologies, good governance and connectivity in the digital era”.

As part of my work on digitalization in Greater Eurasia, I was particularly interested in attending this meeting.

A major part of the event was devoted to questions surrounding energy security, which is a very important factor of cooperation in the OSCE area. All 57 participating states across North America, Europe, and Asia are interested in stable energy supply. Doing energy right is a way to promote progress, security, and prosperity. Orientation towards sustainable development, limiting the use of conventional energy sources, oil conflicts, and cyber attacks make both energy demanders and suppliers search for new solutions. In this regard, the use of renewable resources promises long-term benefits in terms of energy efficiency, new jobs, as well as a secure and resilient energy sector. This is however not possible without peace, which makes the protection of infrastructure crucial. There is no prosperity without peace and no peace without prosperity.

I found it particularly valuable that new technologies were included in the discussion. Blockchain – a system in which a record of transactions made in bitcoin or another cryptocurrency are held across several computers that are linked in a peer-to-peer network – along with big data, are creating new opportunities in the energy sector, for example, in terms of new forms of energy trading. However, they can also pose some risks as they create certain dependencies, thus raising questions of sustainability. For instance, automated driving raises many regulatory issues on how to ensure against cyber attacks and missiles, or how to divide responsibilities between producers and users. Advanced technologies have to be employed safely and efficiently. International organizations could play a vital role in enacting common standards and regulatory norms for digitalization and connectivity in this regard. One grand example here is the single window recommendation, which is a trade facilitation idea that enables international traders to submit regulatory documents at a single location. The idea is that such a system would facilitate trade through good governance.

The establishment of regional communication platforms and the development of science, research, and innovations are of particular importance. Key agents need to talk about secure and clean energy. This could be achieved through intra-institutional cooperation and inclusive dialogue. I believe that institutions like IIASA can play a huge role here.

Talking about new technologies, it is an important task to conduct studies on barriers to trade, especially in the context of blockchain and machine learning technologies in digital trade in order to detect inefficiencies at borders and improve market access. In the energy field, there are many controversial estimates (simultaneously in favor of conventional and renewable energy sources), which also make independent reputable studies essential.

Nadejda Komendantova, a researcher with the Advanced Systems Analysis Program at IIASA also represented the institute at the OSCE meeting, where she moderated a session on protecting energy networks from natural and man-made disasters. The sessions’ participants discussed the impact of these factors on energy security, analyzed opportunities and threats for secure energy networks connected with new technologies, raised questions of resilience, and talked about the mitigation of threats through effective policies and cooperation. The OSCE Critical Energy Infrastructure Protection (CEIP) Digital Training Platform was presented during the session.

To conclude, I would like to emphasize that we need more such constructive and fruitful discussions to catalyze trust, growth, security and connectivity. Partnerships create political will and make open dialogue and mutual support very important. I believe that organizations like IIASA are key to making this possible.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 24, 2019 | Energy & Climate, Poverty & Equity, Sustainable Development

By Pallav Purohit, researcher with the IIASA Air Quality and Greenhouse Gases Program

More than 300 million people in Hindu Kush Himalaya-countries still lack basic access to electricity. Pallav Purohit writes about recent research that looked into how the issue of energy poverty in the region can be addressed.

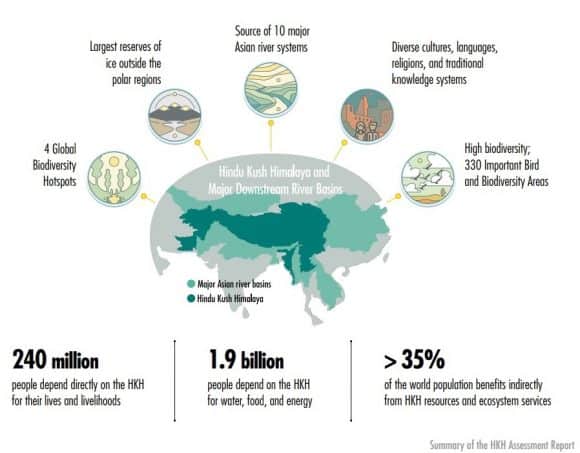

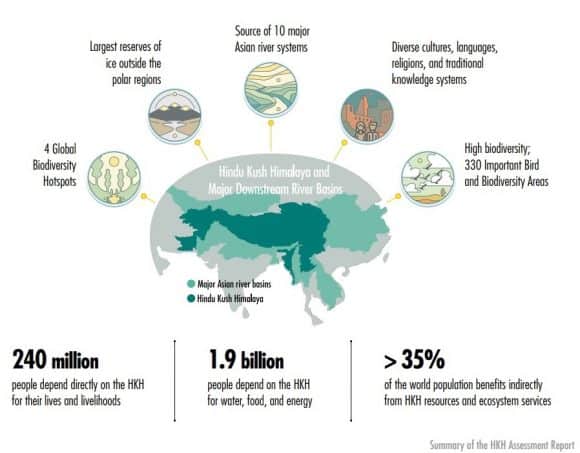

The Hindu Kush Himalayas is one of the largest mountain systems in the world, covering 4.2 million km2 across eight countries: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan. The region is home to the world’s highest peaks, unique cultures, diverse flora and fauna, and a vast reserve of natural resources.

Ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all – the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7 – has however been especially elusive in this region, where energy poverty is shockingly high. About 80% of the population don’t have access to clean energy and depend on biomass – mostly fuelwood – for both cooking and heating. In fact, over 300 million people in Hindu Kush Himalaya-countries still lack basic access to electricity, while vast hydropower potentials remain largely untapped. Although a large percentage of these energy deprived populations live in rural mountain areas that fall far behind the national access rates, mountain-specific energy access data that reflects the realities of mountain energy poverty barely exists.

Source: Wester et al. (2019)

The big challenge in this regard is to simultaneously address the issues of energy poverty, energy security, and climate change while attaining multiple SDGs. The growing sectoral interdependencies in energy, climate, water, and food make it crucial for policymakers to understand cross-sectoral policy linkages and their effects at multiple scales. In our research, we critically examined the diverse aspects of the energy outlook of the Hindu Kush Himalayas, including demand-and-supply patterns; national policies, programmes, and institutions; emerging challenges and opportunities; and possible transformational pathways for sustainable energy.

Our recently published results show that the region can attain energy security by tapping into the full potential of hydropower and other renewables. Success, however, will critically depend on removing policy-, institutional-, financial-, and capacity barriers that now perpetuate energy poverty and vulnerability in mountain communities. Measures to enhance energy supply have had less than satisfactory results because of low prioritization and a failure to address the challenges of remoteness and fragility, while inadequate data and analyses are a major barrier to designing context specific interventions.

In the majority of Hindu Kush Himalaya-countries, existing national policy frameworks currently primarily focus on electrification for household lighting, with limited attention paid to energy for clean cooking and heating. A coherent mountain-specific policy framework therefore needs to be well integrated in national development strategies and translated into action. Quantitative targets and quality specifications of alternative energy options based on an explicit recognition of the full costs and benefits of each option, should be the basis for designing policies and prioritizing actions and investments. In this regard, a high-level, empowered, regional mechanism should be established to strengthen regional energy trade and cooperation, with a focus on prioritizing the use of locally available energy resources.

© Kriangkraiwut Boonlom | Dreamstime.com

Some countries in the region have scaled up off-grid initiatives that are globally recognized as successful. We however found that the special challenges faced by mountain communities – especially in terms of economies of scale, inaccessibility, fragility, marginality, access to infrastructure and resources, poverty levels, and capability gaps – thwart the large-scale replication of several best practice innovative business models and off-grid renewable energy solutions that are making inroads into some Hindu Kush Himalayan countries.

This further highlights an urgent need to establish supportive policy, legal, and institutional frameworks as well as innovations in mountain-specific technology and financing. In addition, enhanced multi-stakeholder capacity building at all levels will be needed for the upscaling of successful energy programs in off-grid mountain areas.

Finally, it is important to note that sustainable energy transition is a shared responsibility. To accelerate progress and make it meaningful, all key stakeholders must work together towards a sustainable energy transition. The world needs to engage with the Hindu Kush Himalayas to define an ambitious new energy vision: one that involves building an inclusive green society and economy, with mountain communities enjoying modern, affordable, reliable, and sustainable energy to improve their lives and the environment.

References:

[1] Dhakal S, Srivastava L, Sharma B, Palit D, Mainali B, Nepal R, Purohit P, Goswami A, et al. (2019). Meeting Future Energy Needs in the Hindu Kush Himalaya. In: The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment. pp. 167-207 Cham, Switzerland: Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-92287-4 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/15666]

[2] Wester P, Mishra A, Mukherji A, Shrestha AB (2019). The Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment: Mountains, Climate Change, Sustainability and People. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-92287-4.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jan 11, 2019 | Alumni, Energy & Climate, IIASA Network, Water, Women in Science, Young Scientists

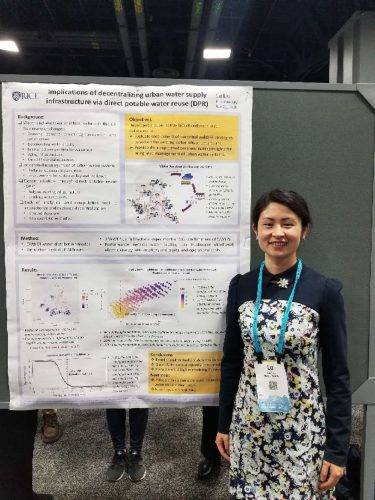

By Lu Liu, postdoctoral research associate at Rice University, USA and IIASA YSSP 2016 participant

I have been attending the American Geophysical Union (AGU) Fall Meeting since 2013 when I was working with the Joint Global Change Research Institute. Ever since then, the AGU Fall Meeting has become one of my most anticipated events of the year where I get to share my research and make new friends.

The first time I attended the AGU Fall Meeting, I was overwhelmed with the size and scale of this conference. There are more than 20,000 oral and poster presentations throughout the week, and the topics cover nearly 30 different themes, from earth and space science, to education and public affairs. I was thrilled to see my research being valued and discussed by people from various backgrounds, and I was fascinated by other exciting research and rigorous ideas that emerged at the meeting.

Lu Liu at 2018 AGU poster session

At this year’s AGU, I presented my poster Implications of decentralizing urban water supply infrastructure via direct potable water reuse (DPR) in a session titled Water, Energy, and Society in Urban Systems. In a nutshell, my poster presents a quantitative model that evaluates the cost-benefits of direct potable water reuse in a decentralized water supply system. The concept of decentralization in an urban water system has been discussed in previous literature as an effective approach towards sustainable urban water management. Besides the social and technical barriers in implementing decentralization, there is a lack of analytical and computational tools necessary for the design, characterization, and evaluation of decentralized water supply infrastructure. My study bridges the gap by demonstrating the environmental and economic implications of decentralizing urban water infrastructure via DPR using a modeling framework developed in this study. The quantitative analysis suggests that with the appropriate configuration, decentralized DPR could potentially alleviate stress on freshwater and enhance urban water sustainability and resilience at a competitive cost. More about this research and my other work can be found here: https://emmaliulu.wixsite.com/luliu.

At the AGU Fall Meeting, I engaged in various opportunities to reconnect with old colleagues and build new professional relationships. What’s better than running into my former YSSP supervisors and IIASA colleagues after two years since I left the YSSP? Although my time spent at IIASA was short, I hold IIASA and the YSSP very close to my heart because the influence this experience has had on my professional and personal life is profound.

I will continue to attend the AGU Fall Meeting for the foreseeable future. After all, we all want to feel a sense of belonging and acceptance in a community, and I am glad I already found mine.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 17, 2018 | Air Pollution, Energy & Climate, Poverty & Equity, Women in Science, Young Scientists

© Stefano Barzellotti | Shutterstock

By Sandra Ortellado, IIASA Science Communication Fellow

When it comes to home cooking in rural India, health, behavior, and technology are essential ingredients.

Consider the government’s three-year campaign to reduce the damaging impacts of solid fuels traditionally used in rural households below the poverty line.

Initiated by the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas, a program called Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (Ujjwala) aims to safeguard the health of women and children by providing them access to a clean cooking fuel, liquid petroleum gas (LPG), so that they don’t have to compromise their health in smoky kitchens or wander in unsafe areas collecting firewood.

According to the World Health Organization, smoke inhaled by women and children from unclean fuel is equivalent to burning 400 cigarettes in an hour.

Nevertheless, an estimated 700 million people in India still rely on solid fuels and traditional cooking stoves in their homes. A subsidy of Rs. 1600 (US $23.47) and an interest free loan attempts to offset the discouraging cost of the upfront security deposit, the stove, and the first bottle of LPG, but this measure hasn’t been able to change habits on its own.

Why? Although the government has made an overwhelming effort to increase access, interconnected factors like cultural norms, economic trade-offs, and convenience require an in-depth analysis of human behavior and decision-making.

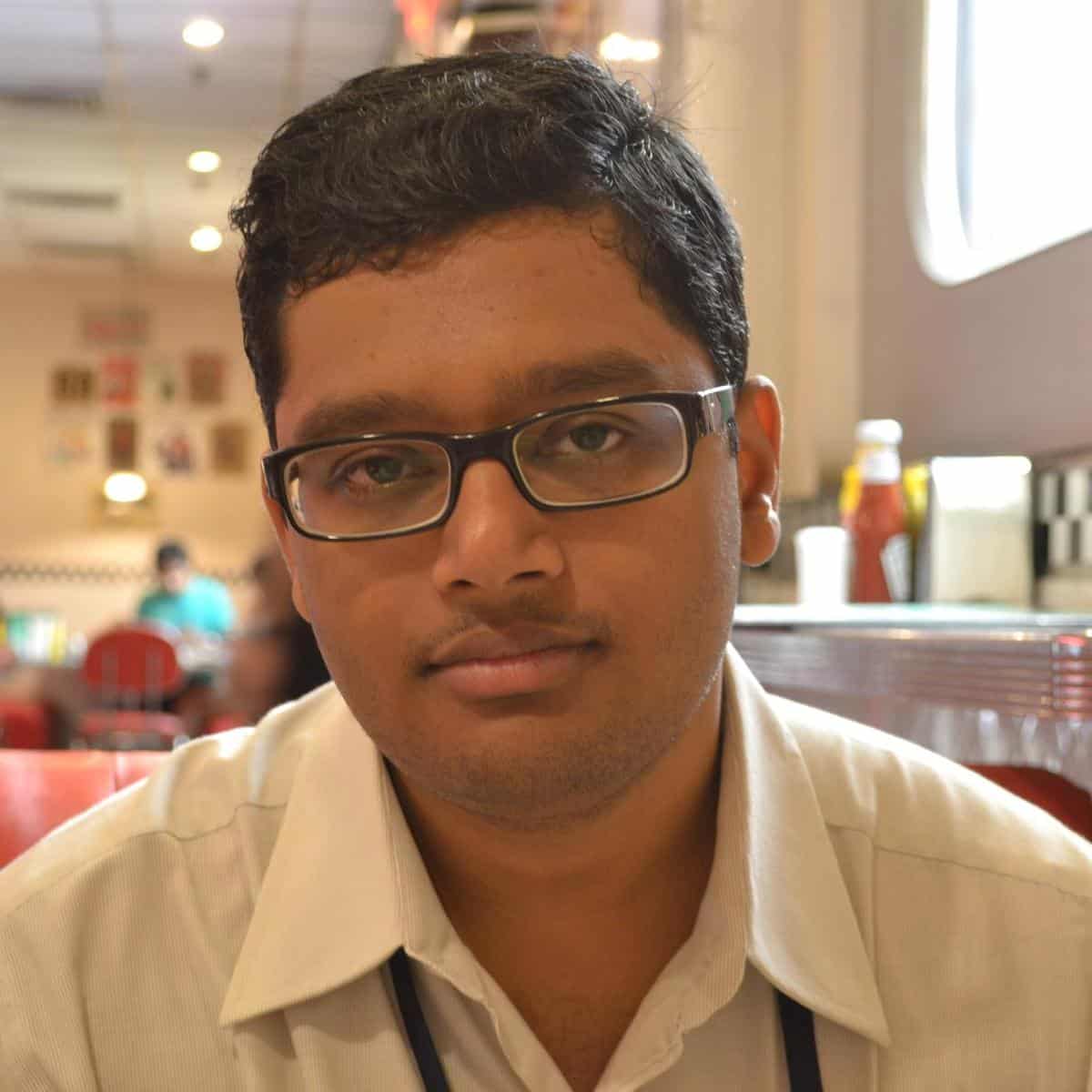

Abhishek Kar, 2018 YSSP participant ©IIASA

That’s why Abhishek Kar, a researcher in the IIASA Energy Program and a participant in the 2018 Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP), has designed a study to explore how rural households make choices about access and usage. Borrowing from behavior change and technology adoption theories, he wants to know whether low-cost access is enough incentive for Ujjwala beneficiaries to match the general rural consumption trends, and more importantly, how to translate public perception into a behavior change.

“I think it’s really important to look into the behavioral aspect,” said Kar in an interview. “If you ask someone if they think clean cooking is wise they may say yes, but if you say do you think it is appropriate for you? The moment it becomes personalized the answers can vary.”

Kar knows that although more than 41 million LPG connections have been installed, installment of the connection does not necessarily equate to use. By gathering data on LPG refill purchases and trends, along with surveys that identify biases in the public’s perception, he wants to know how to convince rural BPL households to maintain the habit of using LPG regularly, even under adverse conditions like price hikes. If LPG is used only sporadically, LPG ownership won’t significantly reduce risk for some household air pollution (HAP)-linked deadly diseases, like lower respiratory infections and stroke.

Unfortunately, even the substantial efforts the government has made to improve LPG supply has not changed the public’s perception of its accessibility in the long term, nor its consumption patterns in the first two years. At least four LPG refills per year would be needed for a family of five to use LPG as a primary cooking fuel, which is not currently happening for the majority of Ujjwala customers.

Because the majority of Ujjwala beneficiaries have cost-free access to solid fuels from forest and agricultural fields, there is less incentive for these families to use LPG regularly instead of sporadically. Priority households for Ujjwala, especially those with no working age adults, are often severely economically disadvantaged and can’t afford to buy LPG at regular intervals.

Furthermore, unlike LPG, a traditional mud stove is more versatile and can serve dual purposes of space heating and cooking during winter months. Many prospective customers are also hesitant about the inferior taste of food cooked in LPG, the utility of the mud stove’s smoke as insect repellent, and the trade-off of expenses on tobacco and alcohol with LPG refills.

As per past studies, even the richest 10% of India’s rural households (most with access to LPG) continue to depend on solid fuels to meet ~50% of their cooking energy demand. This suggests that wealth is not the only stumbling block in the transition process.

“Whatever factors matter in the outside world, my working hypothesis is that every decision is finally mediated through a person’s attitude, knowledge, and perceptions of control,” said Kar. According to Kar, interventions can be specifically targeted to address factors that are perceived negatively either by informing people or doing something to improve that factor. Nevertheless, developing effective interventions is no simple task.

Even with a background in physics and management and eight years of experience helping people transition from one technology to another, Kar says he is grateful to have the input of a variety of scholars at IIASA, each with a different perspective and a different set of core skills and experiences. Working in the Energy program alongside IIASA staff and fellow YSSPers from all over the world, Kar puzzles out the unsolved challenge of how to create change for the rural poor.

“That has been one of my drivers, I take it as an intellectual challenge,” said Kar. “Is there a systems approach to the problem?”

For now, Kar is happy if he can return at the end of the day to his family, which he brought with him to Austria during his time as a YSSP participant, feeling like he is opening the door to a vast literature on technology adoption and human behavior, yet untapped in the field of cooking energy access.

“This research is only a very small baby step into trying something different,” said Kar, “I think this sector has so many unanswered questions, if I can at least flag that there is a lot of literature out there in other domains and maybe we can use some of it, I think that would be good enough for me.”

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.