Dec 21, 2015 | Demography

In recent years the world has been in the grips of the worst refugee crisis since the horrors of WWII. Between January and August 2015 over 44,000 people applied for asylum in Austria alone. While much attention has been focused on immigration and asylum policies, there is a lack of data on the actual people; what are their backgrounds, qualifications, and expectations?

To address this, IIASA scientists are working with colleagues from the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (IIASA, VID/ÖAW, WU). Together the three institutions have designed a questionnaire for refugees in Austria, the first survey of its kind in German-speaking countries.

The team—consisting of over 40 researchers, students, and volunteers—is aiming for around 500 interviews with people seeking asylum in Austria, and the survey is carried out in Arabic, Farsi, and English. Zakarya Al Zalak, IIASA researcher in the World Population Program, former director of the Damascus Statistical Technical Institute, and a Syrian himself, speaks to science writer Daisy Brickhill about directing the work.

Why are you carrying out this survey?

We know almost nothing about the refugees as individuals. Who are these people? How much education have they received? What are their qualifications? What are their hopes and values? This kind of information is vital, because it can assist policymakers to design strategies to help these people integrate into Austrian society.

Training for the survey. Photo credit: Judith Kohlenberger

What kind of questions do you ask?

There are six sections to our questionnaire. The first covers demography—things like age, sex, ethnicity, and religion. Even on these basic characteristics there is very little data. The second is about education. How long did they stay in school? What are their qualifications?

For the third section we focus on employment, asking whether they had a job before leaving their native country, and what their profession was. This will help assess the skills these people can bring to the Austria, and where they might be able to work. This is particularly important for integration, as it can help policymakers see where they might fit in to Austria’s workforce.

We use all kinds of questions and measures to get the most information possible. For example, when asking about health, we test the participants’ hand-grip strength. Previous IIASA research has shown that this is related to markers of aging, future disability, cognitive decline, and the ability to recover from hospital stays.

In the fifth section we ask about family. This is important because although many refugees are men travelling alone, they may be planning to bring their family once they have made a life for themselves.

You mentioned attitudes and values, how do you find out about these things with a simple questionnaire?

In the last section of the questionnaire we use several different approaches to explore attitudes. We ask whether they would mind if their children were taught about other religions at school, for instance. We also ask about their views on abortion and gender equality, among other things.

What are the next steps?

We finish sampling soon, so we are hoping to publish the preliminary results in January 2016. However, the most important part of the work is in the next stage. We have asked for participants’ contact details, and our plan is that we will reconnect with these people after some time, eight or nine months, say. At that point we can ask more about how they are finding life in Austria, and whether integration is going well. Have they taken a German language course, for example? Do they have work? Have they received training?

If we are unable to reach some people for follow-up there is a possibility of recruiting new participants. Although we will not have the data from the initial survey we can still ask them how long they have been here, and how their integration is going.

It must be difficult seeing your fellow Syrians in such dire straits.

Before coming to Austria, I worked with refugees in my own country. It seems strange to think of now, but at that time there were Iraqi people who had fled to Syria to seek asylum. Now, we are finding people who are “double refugees,” first fleeing to Syria from Iraq and then, as the situation in Syria worsened, from Syria to Austria. It must be an extremely hard journey. I very much hope this work helps policymakers to make things easier for them.

Austrian Academy of Sciences Press Release

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 10, 2015 | Demography, Young Scientists

By Anne Goujon, IIASA World Population Program

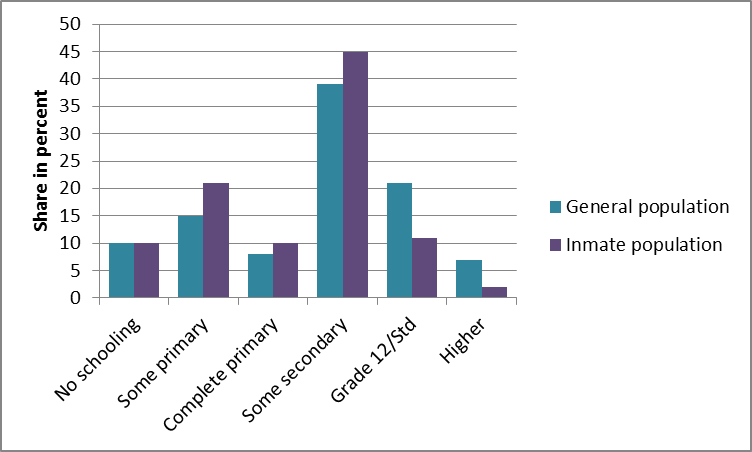

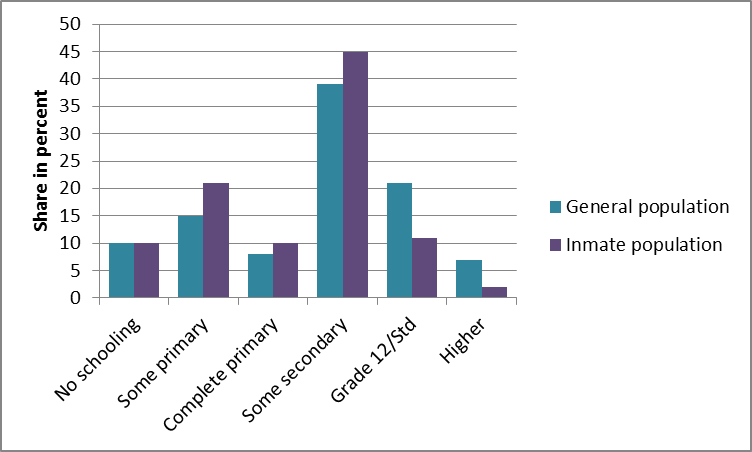

If you live in South Africa and did not complete high school then your chances of committing crime, being caught, and sent to jail are pretty high. This is what we can tell from comparing the education characteristics of the population of inmates in South Africa with that of the population who was not in jail. A recent study that I conducted with a team of African and European researchers in the framework of the Southern African Young Scientists Summer Program confirms some findings from previous research, such as this 2010 study that found that education has a statistically significant effect on crime.

South Africa spends about 8 billion dollars a year on public order and safety. Violence and related injuries are the second primary cause of death in South Africa, and in the last 10 years, the prison population rate has been in a range from 300 to 400 per 100,000 people, one of the highest rates in the world.

© straystone | Dollar Photo Club

South Africa is still plagued with the after-effects of its apartheid history, which enforced sub-standard education for different racial groups, creating a polarized society. The disparity in education between white and other racial clusters actually widened after the fall of the apartheid government. At the same time—and not unrelatedly, as shown by our study—the apparently peaceful transition to a democratic regime was accompanied by a rise of crime and violence, a gauge of the dichotomized South African society and its high levels of social exclusion and marginalization.

Indeed, our analysis of the 2001 census shows that the effect of education on criminal engagement – meaning in this study actually serving time in prison for a crime – differs by race. This suggests that there is an interaction effect between race and education. The negative relationship between being highly educated and the likelihood of being incarcerated is linear for respondents of mixed ethnic origin (or “colored” according to the South African classification), Indians, and to a lesser extent also for Africans. For white respondents, however, the effect of education creates a bell-shaped graph, with the richest and poorest people less likely to be in prison, and the medium levels of education associated with the highest probability to be in prison.

Share of the general and inmate population by level of educational attainment, South Africa, 2001

We also looked at the empirical results from a sample drawn in the Free State province—a crime hot spot – which indicated that a person’s native language, a proxy for race and place of origin, has a statistically significant influence on the likelihood to commit a contact . We also found that the probability of committing contact crimes, including vandalism, threat, assault, and injury, decreased with years of education, while the likelihood of committing economic crimes, including tax fraud, increases with years of education

This research provides another good incentive to invest in education in South Africa, and particularly to insist on all children completing upper secondary education finishing with grade 12. Education statistically significantly decreases the probability of engaging in criminal activity. Hence, it should be included in the National Crime Prevention Strategy, particularly in some targeted provinces within South Africa.

Reference

Jonck, Petronella, Anne Goujon, Maria Rita Testa, John Kandala, 2015, Education and crime engagement in South Africa: A national and provincial perspective. International Journal of Educational Development, 45: 141–151. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.10.002. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0738059315001248

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 20, 2015 | Demography

By Samir KC, IIASA World Population Program (Originally published on the Globalist)

Africa is rising fast, at least demographically. Today, the continent is home to more than a billion people, of which some 950 million of them living in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The UN, for its part, predicts that the continent’s population will double by 2050 — and then double again by the end of this century, to make it a continent of more than 4 billion.

This staggering number – equal to the entire world population as recently as 1980 — may concern many doomsayers, but in reality it contains a lot of good news.

One main reason for the increase is that better living conditions reduce child mortality and create opportunities for longer and healthier lives.

This crucial shift results in a rapidly rising number of adults who are driving the continent’s demographic future.

That development is similar to what occurred in Asia over the last 30 years, which in turn had previously occurred in the Western world.

Barry Aliman, 24 years old, bicycles with her baby to fetch water for her family, Sorobouly village near Boromo, Burkina Faso. Photo by Ollivier Girard for Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR).

UN’s optimistic projections

However, as Wolfgang Fengler and I highlighted recently, in contrast to the UN Population Division’s projections, it is far from certain that Africa will even reach a population totaling 3 billion, and the world 10 billion, by the end of this century.

According to our projections at the Wittgenstein Center, projecting population by age, sex, and educational attainment for almost all countries of the World, Africa’s population may only rise to some 2.6 billion by 2100. That number is only 60% of the 4.4 billion predicted by the UN.

The differences are stark across the biggest African countries. In some countries’ cases, the UN’s forecast is much higher – in fact, even more than double (e.g. Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, Niger, Angola and Mozambique, See table).

Data: UN Population Division and The Wittgenstein Center

How is it possible to have such sharp differences in population projections, which are generally known for their accuracy?

The rate of Africa’s future population growth will mostly depend on two factors. First, the number of children per woman and, second, the chance of those children to survive (which is now much higher, thanks to improving living conditions).

Decline in fertility rate

In any projection far into the future, even a small difference in the number of children per woman makes a big difference in total population numbers when its effect is viewed cumulatively over several generations.

At the core of the two vastly different forecasts is this: The UN assumes that fertility will only decline slowly to 3 children per woman by 2050 — and then 2.6 children by 2070.

These projections are based on the observation that, while fertility has stagnated in parts of Africa in the last decade, it will decline more slowly than it had been declining in other parts of the world.

In contrast, the Wittgenstein Center assumes that the patterns that we will come to observe in Africa are not going to be much different from the case in the other regions of the world, as they went through their demographic transitions.

Once countries urbanize and citizens become wealthier, fertility declines, everywhere.

The most important factor is women’s education. Already today, an Ethiopian woman with secondary education has on average only 1.6 children, compared to a woman with no education who has 6 children.

This relationship is true across Africa (see figure).

Source: Demographic and Health Surveys

Similar trend in Asia

We know that access to education is expanding across Africa. There is even talk of an education dividend.

Once all girls go to school and stay there longer, they will have fewer children, especially as they will also be exposed to a more modern lifestyle, be it through TV, the cell phone and the fact that Africa is urbanizing rapidly.

This has also been the experience in Asia. It took about 20 years in Asia for its fertility to decline from more than 5 children per woman during early 1970s to less than 3 children per woman in early 1990s.

Similarly, India took about 20 years for its fertility to decline from 4.7 children per woman in early 1980s to 3.1 by early 2000s.

With new development and the plans for the better future in the making, it won’t be a surprise if the average African family would have only three children as soon as 2035.

If that assumption bears out, then Africa cannot reach 4 billion — and the world would peak this century at below 10 billion.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Sep 25, 2015 | Sustainable Development

By Wolfgang Lutz, IIASA World Population Program Director and Founding Director of the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (Originally published on the World Economic Forum Agenda Blog.)

Wolfgang Lutz

Few people would dispute the importance of education in our lives and those of our children. For good reasons, in virtually all industrialized countries, education is compulsory for everybody for at least 10 years.

In developing countries, however, 780 million women and men remain illiterate. Moreover, about 60 million children of school age are not at school.

Yet instead of making a concerted global effort to bring all children to school, less than 4% of official development assistance funds basic education. Over the past seven years, UNESCO and UNICEF report a decline in basic education.

Many think education is an aspect of social development that comes as a by-product of economic growth. This is wrong. Education is an absolutely necessary precondition of economic development.

Bill Clinton’s famous mantra, “It’s the economy, stupid!”, may be a useful slogan for an election campaign, but it is misleading in setting the priorities for sustainable development. It’s not primarily the economy, nor money, that makes the world go round and determines progress in human well-being. Much more important than the content of people’s wallets is the content in their heads. And what is in our heads is formed and enhanced by education which, in turn, helps fill the wallets, improves health, improves society and the quality of institutions, strengthens resilience at all levels and even makes people happier.

I could discuss the ample scientific statistical analysis to prove the transformative role of education in development. But more convincing may be historical success stories.

Finland was one of the poorest corners of Europe in the late 19th century. In 1868-1869 it suffered the last great famine in Europe not induced by political events. Almost half of the children died in this hopelessly underdeveloped and poorly educated economy based on subsistence agriculture.

After that tragedy, the Lutheran Church, supported by the government, launched a radical education campaign: young people could marry only after they passed a literacy test. The number of elementary school teachers increased by a factor of 10 over just three decades and by the beginning of the 20th century all young men and women in Finland had basic education. In 1906 Finland was the first country in Europe to grant women the right to vote and the subsequent economic development, based primarily on human capital, made Finland one of the world’s leaders in technology, innovation and, as a result, competitiveness.

In the early 1960s, Mauritius was a textbook case of a country stuck in the vicious circle of high-population growth, poverty and environmental destruction. Following the advice of scientists such as James Meade, the government launched a (strictly voluntary) family planning programme together with a huge push on female education. This led to rapid fertility decline plus economic growth, first through the textile industry based on semi-skilled female workers, then in upmarket tourism and more recently in banking and high-tech information technology. Mauritius is the only such success story in sub-Saharan Africa. The country managed to escape the vicious circle of poverty and underdevelopment through investment in human capital.

University students in Malaysia. © Nafise Motlaq / World Bank

Japan, Singapore, South Korea and finally China have similar stories but the timing is different. The Chinese experience shows that such success is not confined to remote and tiny island or city states. The highly elitist appreciation of education in Confucian tradition became transformative for the country once it was combined with the (originally) protestant approach of a broad-based education. Again, these countries built their stunning success stories primarily on improvements in human capital and without significant raw materials or international assistance. Economic growth followed the education expansion.

There is little doubt about the cause and effect between education and human well-being. Neurological research shows that every learning experience builds new synapses making our brains physiologically different for the rest of our lives. Education expands the personal planning horizon and leads to more rational decisions and less fatalism. It clearly empowers people to access more information, contextualize it and make conclusions that are more conducive to personal and societal well-being.

Well educated people are better at adopting good habits such as physical exercise, safe sex or quitting smoking. Education has many other effects on health from lowering child mortality to postponing disability and cognitive decline in old age, besides the commonly cited effects on income and employment. There is even the surprising finding that education makes people happier despite the fact of making them more aware of potential problems. Unsurprisingly, universal education reduces vulnerability to natural disasters and helps people adapt to climate change.

About a decade ago, I discussed some of this evidence with the Nobel laureate Gary Becker. He said: “Well, when I think about it, I cannot think of anything for which I rather would be less educated than more educated.”

Now we need to educate the economists and policy-makers to make it a much higher priority in the development agenda.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 11, 2015 | Demography

IIASA demographer Erich Striessnig talks about new research linking population change with climate change scenarios.

What does your research say about population and climate?

In our recent review article published in the journal Population Studies, we give a summary of much of the work that has been carried out over the past few years both at IIASA and at the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (IIASA, VID/ÖAW; WU) on the contribution of changes in population size and structures to greenhouse gas emissions, as well as societies’ capacity to adapt to climate change. Similar to Mia Landauer in last week’s blog entry, we emphasize the importance of addressing challenges to mitigation and adaptation jointly.

What’s new or unexpected in this study?

The main novelty behind our approach is the explicit inclusion of the full population detail by age, sex, and educational attainment in assessments of societies’ future adaptive and mitigation potential. This is exemplified in the context of IPCC-related climate change modelling which until recently has included only very limited information on the future of population. The new Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs), which were developed with a huge contribution by IIASA, are an important step to overcoming this situation and to make models of both future greenhouse gas emissions, as well as vulnerability and adaptive capacity with respect to climate change far more realistic.

Population characteristics – not just numbers – make a major impact on greenhouse gas emissions as well as people’s ability to adapt to a changing climate. ©Chris Ford via Flickr

Why is it important to consider the composition of population in regards to future climate change issues?

When thinking about the challenges of the future, it is important also to think about the capabilities that future societies will have to face them. I don’t mean that we should simply lean back and wait for science-fictional future technologies to solve all the problems of humanity, but a look at the changing future composition of populations around the world gives reason for optimism that future societies will be better at preparing, coping, and dealing with the consequences of yet unavoidable climate change than we are today.

What are the links between education and climate change?

Particularly in the developing world, education leads to reduced poverty. But economic growth and the resulting greater affluence, and consumption, also increases global CO2 emissions. So on a first look, education appears to worsen climate change. This has made some environmental activists skeptical about the value of education in the context of mitigation. But to avoid playing poverty eradication and well-being against climate change mitigation, it is necessary to look at behavioral differences at given levels of income. In fact, better education has been shown to be related to more eco-friendly consumption behavior, especially when it comes to home energy use and transportation, two of the main drivers of climate change. In addition to that, education has also been a major driver of technological advancements in the transition to cleaner energy sources.

Research shows that people’s education levels also play a role in how adaptable they are to potential climate-related impacts such as storms and floods. ©Aldrich Lim via Flickr

How do the new SSPs bring demography into the study of climate change?

Population growth is undoubtedly one of the main drivers of greenhouse gas emissions and thus climate change. What’s far less acknowledged is the importance of differential climate impact depending on demographic characteristics. Groundbreaking work by researchers from IIASA and the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) featured in the article has shown that people have different footprints when they are young than when they are old and that household consumption differs between rural and urban dwellers. Providing different scenarios for the future composition of populations by age, sex, and educational attainment, the new SSPs for the first time allow researchers from different fields to study the dynamics between population and climate change within a common reference frame.

References

Lutz W, Striessnig E (2015) Demographic aspects of climate change mitigation and adaptation. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography, 69(S1):S69-S76 (April 2015). doi: 10.1080/00324728.2014.969929

O’Neill, Brian C., Michael Dalton, Regina Fuchs, Leiwen Jiang, Shonali Pachauri, and Katarina Zigova. “Global Demographic Trends and Future Carbon Emissions.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 (October 2010): 17521–26. doi:10.1073/pnas.1004581107.

Note: This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.