May 28, 2018 | Air Pollution, Climate, Climate Change, Ecosystems, Energy & Climate, Women in Science

By Beatriz Mayor, Research Scholar at IIASA

On 14 and 15 May, Vienna hosted two important events within the frame of the world energy and climate change agendas: the Vienna Energy Forum and the R20 Austrian World Summit. Since I had the pleasure and privilege to attend both, I would like to share some insights and relevant messages I took home with me.

Beatriz Mayor at the Austrian World Summit © Beatriz Mayor

To begin with, ‘renewable energy’ was the buzzword of the moment. Renewable energy is not only the future, it is the present. Recently, 20-year solar PV contracts were signed for US$0.02/kWh. However, renewable energy is not only about mitigating the effects of climate change, but also about turning the planet into a world we (humans from all regions, regardless of the local conditions) want to live in. It is not only about producing energy, about reaching a number of KWh equivalent to the expected demand–renewables are about providing a service to communities, meeting their needs, and improving their ways of life. It does not consist only of taking a solar LED lamp to a remote rural house in India or Africa. It is about first understanding the problem and then seeking the right solution. Such a light will be of no use if a mother has to spend the whole day walking 10 km to find water at the closest spring or well, and come back by sunset to work on her loom, only to find that the lamp has run out of battery. Why? Because her son had to take it to school to light his way back home.

This is where the concept of ‘nexus’ entered the room, and I have to say that more than once it was brought up by IIASA Deputy Director General Nebojsa Nakicenovic. A nexus approach means adopting an integrated approach and understanding both the problems and the solutions, the cross and rebound effects, and the synergies; and it is on the latter that we should focus our efforts to maximize the effect with minimal effort. Looking at the nexus involves addressing the interdependencies between the water, energy, and food sectors, but also expanding the reach to other critical dimensions such as health, poverty, education, and gender. Overall, this means pursuing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Vienna Energy Forum banner created by artists on the day © UNIDO / Flickr

Another key word that was repeatedly mentioned was finance. The question was how to raise and mobilize funds for the implementation of the required solutions and initiatives. The answer: blended funding and private funding mobilization. This means combining different funding sources, including crowd funding and citizen-social funding initiatives, and engaging the private sector by reducing the risk for investors. A wonderful example was presented by the city of Vienna, where a solar power plant was completely funded (and thus owned) by Viennese citizens through the purchase of shares.

This connects with the last message: the importance of a bottom-up approach and the critical role of those at the local level. Speakers and panelists gave several examples of successful initiatives in Mali, India, Vienna, and California. Most of the debates focused on how to search for solutions and facilitate access to funding and implementation in the Global South. However, two things became clear. Firstly, massive political and investment efforts are required in emerging countries to set up the infrastructural and social environment (including capacity building) to achieve the SDGs. Secondly, the effort and cost of dismantling a well-rooted technological and infrastructural system once put in place, such as fossil fuel-based power networks in the case of developed countries, are also huge. Hence, the importance of emerging economies going directly for sustainable solutions, which will pay off in the future in all possible aspects. HRH Princess Abze Djigma from Burkina Faso emphasized that this is already happening in Africa. Progress is being made at a critical rate, triggered by local initiatives that will displace the age of huge, donor-funded, top-down projects, to give way to bottom-up, collaborative co-funding and co-development.

Overall, if I had to pick just one message among the information overload I faced over these two days, it would be the statement by a young fellow in the audience from African Champions: “Africa is not underdeveloped, it is waiting and watching not to repeat the mistakes made by the rest of the world.” We should keep this message in mind.

Mar 7, 2018 | Energy & Climate

By Jessica Jewell, David McCollum, Johannes Emmerling, Christoph Bertram, David E.H.J. Gernaat, Volker Krey, Leonidas Paroussos, Loïc Berger, Kostas Fragkiadakis, Ilkka Keppo, Nawfal Saadi, Massimo Tavoni, Detlef van Vuuren, Vadim Vinichenko, Keywan Riahi

Our recent paper about our research on the effects of removing fossil fuel subsidies, published in Nature on February 8, 2018, generated a lot of comment and debate.

Here, we respond to three important themes raised in these comments. The first concerns the interpretation of our findings about the significance of subsidy removal for reducing CO2 emissions, the second concerns our approach to modeling and the data we used, and the third relates to policy options for more effective subsidy reform.

© Shutterstock / huyangshu

What are fossil fuel subsidies and why are they interesting for climate?

Fossil fuel subsidies are government interventions which decrease the price of fossil fuels below the market price. They can go to supporting the extraction of oil, gas, and coal (production subsidies) or making fuels cheaper for consumers (consumption subsidies) and amounted to over US$400 billion in 2015. There is a certain irony in that so many governments signed on to the Paris Agreement in 2015 yet in that same year many of those same governments spent so much money making fossil fuels cheaper.

How much would removing these subsidies help climate change mitigation efforts? How does it compare to what countries have already pledged to do for the climate under the Paris Agreement?

Comparing emission reductions from subsidy removal to key climate targets

Some commenters claim that it is already known that the effect of removing fossil fuel subsidies on emissions is limited. However, according to the authoritative Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fifth Assessment Report (IPCC AR5), subsidy reform “can achieve significant emission reductions”. This view also is evident in the political sphere as: the Friends of Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform, a group of countries called fossil fuel subsidy reform “the missing piece of the puzzle in the fight against climate change”.

Our findings are that fossil fuel subsidy removal would lead to a 1-4% reduction in CO2 emissions in the energy sector by 2030 if oil prices stay low, and 1-5% if oil prices rise again, compared to the rise in emissions if subsidies are maintained, the baseline. It means that subsidy reform is a modest contribution to the global reductions required to achieve 2°C in a least-cost pathway, 27-57% by 2030.

More importantly, in our paper we compare emission reductions from subsidy removal not to this ideal goal, but to the actual targets pledged in the context of the Paris Agreement. Globally, Paris pledges would reduce emissions against the baseline in the energy sector by 9-13% in 2030 (under a moderate growth baseline) which is a larger reduction than fossil fuel subsidy removal would deliver. Under both the Paris climate pledges and fossil fuel subsidy phase-out global emissions would continue to rise whereas to achieve the 2°C target they should peak and eventually decline.

Identifying the regions with greatest impact

This global assessment is only part of our study. In addition, we show how the impacts of subsidy removal are different by region. In the major oil and gas exporting regions (Middle East and North Africa, Russia and its neighboring countries, and Latin America), removing fossil fuel subsidies lowers emissions by the same amount or more than these countries’ Paris pledges. Government revenues in these regions largely come from energy exports, which are squeezed by today’s low oil prices. Lowering government spending by removing subsidies is a real political opportunity to reduce emissions in these regions.

In other developing and emerging economies (India, China, the rest of Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa), removing fossil fuel subsidies has less of an effect on emissions than these countries’ Paris pledges. In addition, the number of people who might be affected by subsidy removal in these regions is higher, simply because there are many more people living below the poverty line, for whom subsidies make the most difference. Taken together, these two findings frame one of our main results: that subsidy removal would be most useful for the climate precisely in the regions where it would affect fewer people living below the poverty line.

Data on subsidies

The second theme we would like to address relates to our data and modeling. Some commenters claimed that we underestimate both production subsidies and the effect of their removal.

According to data from the IEA and OECD only about 4% of subsidies are production subsidies. The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) and Overseas Development Institute (ODI) publish an independent estimate based on their own definition and approach. Extrapolating to the global level, production subsidies would be about 14% in 2013 under their approach. We ran a sensitivity analysis using this higher production subsidies estimate. This did not change our findings (discussed in the Supplementary Information to our article).

Some commenters claimed that our study does not consider electricity production subsidies. This is also not true. We use the IEA data where power generation subsidies are captured in electricity subsidies. The SI discusses how each model integrates electricity subsidies.

There are other, fragmented estimates for electricity generation subsidies in individual countries, which generally take a different view of subsidies. For example, the recent report from IISD on Chinese subsidies to coal-fired power plants indicates that in 2014 and 2015, between 89% and 97% of these subsidies went to incentivize air pollution control equipment or closing inefficient plants. According to the same report, these subsidies also dropped by half from 2014 to 2015. Few governments would consider this as an environmentally-harmful subsidy, and removing such support will increase, not decrease emissions.

For our main analysis, we relied on IEA and OECD data for both production and consumption subsidies because these inventories are aligned with governments’ own estimates which are prepared as part of the G20 pledge to remove subsidies from 2009 reaffirmed in 2016. By using the same input data as governments and international organizations who are pledging or considering fossil fuel subsidy removal, we ensure the policy relevance of our results for these actors.

Estimating the effects of production subsidy removal

There were several comparisons of our results with those reported in a recent paper by Erickson et.al. in Nature Energy, which found that under the currently low oil prices, removing production subsidies in the US would make several oil fields unprofitable and eventually result in their closure. We find contrasting these two papers misleading as they ask very different research questions. Our study does not investigate how many oil fields in the US or elsewhere will become unprofitable after subsidy removal, but looks at the global effect of subsidy removal on emissions by taking into account trade in fossil fuels, the demand response and potential substitution of fuels and technologies. Erickson and his colleagues do not ask how much emissions will change as a result of closed oil fields. These are two very different questions.

Erickson and his colleagues compare the amount of carbon embedded in the oil reserves that may become unprofitable due to subsidy removal, to how much carbon the US would be allowed to emit under a stringent climate target. This creates an impression that they investigate the impact of removing oil production subsidies on US emissions. However, calculating the emission impact from removing oil production subsidies requires not only calculating the emissions embedded in foregone oil production, but also the possible emissions resulting from replacing this lost oil with other fuels, or changes in demand, for example if Americans choose to drive less if wells are closed, or if the US imports oil instead. We use these types of feedbacks in our models to calculate the emissions effects of subsidy removal (both consumption and production).

Redirecting subsidy funds

The third theme raised in the comments to our article was why we did not model redirecting subsidies to supporting renewable energy. While this is a very tempting question to ask from a climate perspective, and certainly one which we could do in our models, we did not consider it a realistic policy to be prioritized in our scenarios. In most countries fuel subsidies were introduced to support those on low incomes, although it is an inefficient way to do so. A state budget deficit and today’s low oil prices can often prompt successful subsidy reform. Indonesia for example recently expanded spending on infrastructure and programs to reduce poverty, while India introduced vouchers for cooking fuels. Iran, meanwhile introduced universal health coverage.

Fossil fuel subsidies do need reform

We would like to express our agreement with two comments, one from Ian Parry who wrote a commentary to our paper in Nature, and another from David Victor in his statement to Scientific American, that there are many reasons to reform fossil fuel subsidies other than emissions reductions. Our article does not cover these reasons and should not be interpreted as a comprehensive assessment of all aspects of subsidy removal.

We do however hope that our transparent and rigorous assessment of the effects of subsidy removal on CO2 emissions and energy use will support realistic and effective subsidy removal policies, and help in understanding the relative importance of a range of emission-reduction measures needed for achieving the ambitious long-term targets of the Paris Agreement.

As some commenters pointed out, we need all tools in the box to combat the enormous challenge of climate change. We fully agree. At the same time, we also believe in the need to understand how much each tool can do and where it can be most effective. This is exactly what our study answers.

Reference

Jewell J, McCollum, D Emmerling J, Bertram C, Gernaat DEHJ, Krey V, Paroussos L, Berger L, Fragkiadakis K, Keppo I, Saadi, N, Tavoni M, van Vuuren D, Vinichenko V, Riahi K (2018) Limited emission reductions from fuel subsidy removal except in energy exporting regions. Nature DOI: 10.1038/nature25467

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jan 22, 2018 | Energy & Climate, Poverty & Equity

By Narasimha Rao, Project Leader of the Decent Living Energy (DLE) Project, IIASA Energy Program

Is there a conflict between reducing global income inequality and combating climate change? This seems like an odd question, given that these challenges have a lot in common. Raising the living standard of the poor for example, makes them resilient to climate impacts; less inequality can mean more political mobilization to establish climate policies; and changes in social norms away from material accumulation can reduce inequality and emissions. Academics have however been curious about the following phenomenon: In many countries, a dollar spent at higher income levels is less energy intensive than at lower income levels (known as “income elasticity of energy”). That is, rich people – although they consume much more in total – spend additional income on services or can afford energy-efficient goods, while the new middle class buy energy-intensive goods, like appliances and cars.

Many imagine China as a template for this type of fast growth. If globally significant, this effect would imply that growth that is more equitable would also be more emissions-intensive, and that we would have to pay particular attention to ensuring that climate policies reach the rising middle class in developing countries. While several studies have examined this phenomenon in specific countries, no one has examined its global significance. We set out to do that.

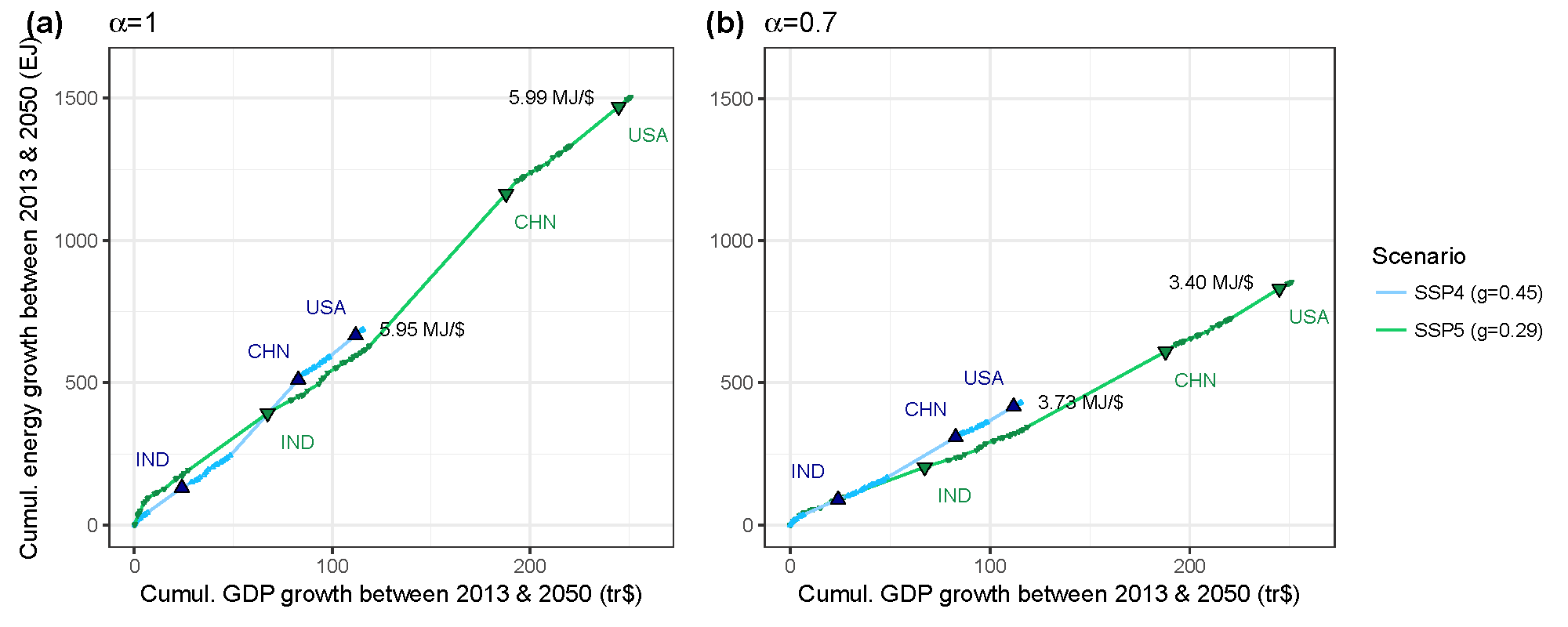

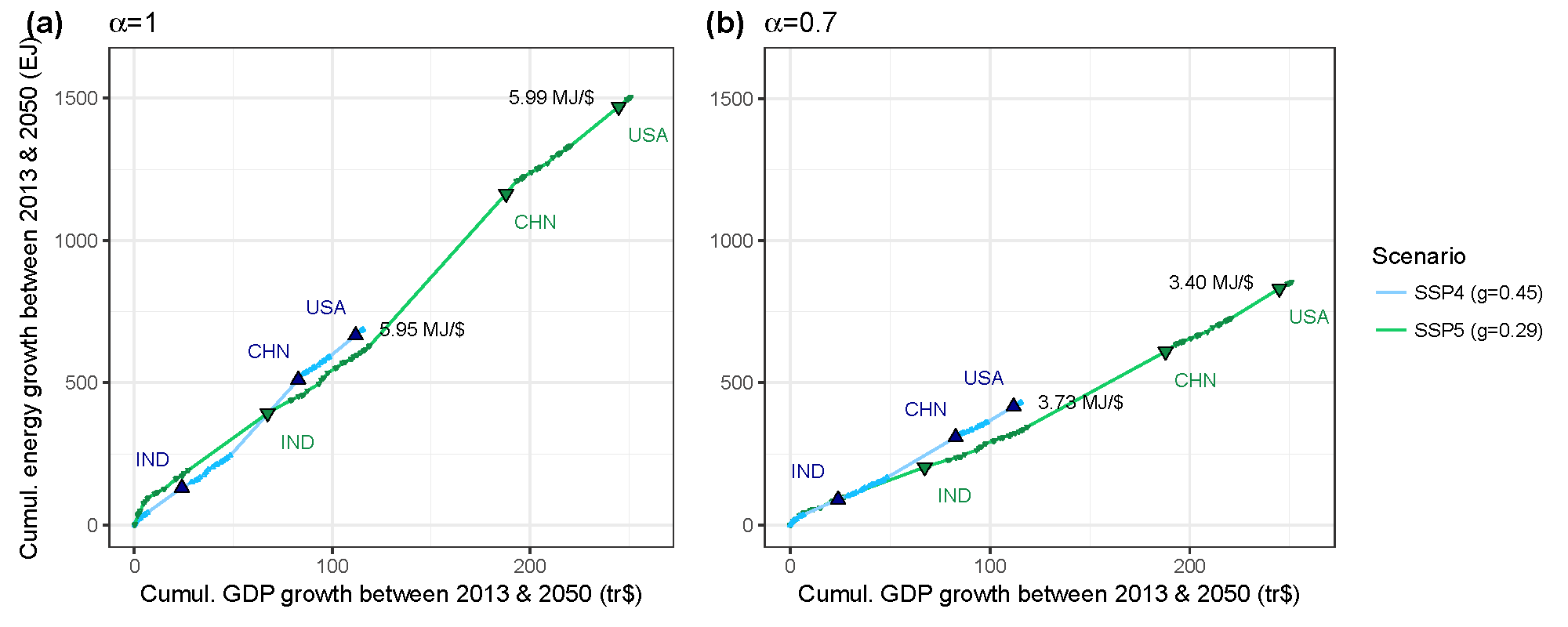

Energy intensity (MJ per $) lower in a high-growth, low inequality world (green line, Gini=0.29) compared to a low-growth, high inequality world (blue line, Gini=0.45). Gini reflects between-country inequality only.

Our analysis suggests that the energy-increasing effect of lowering inequality is more of a distraction than a concern. We compared scenarios of equitable and inequitable income growth, both within and between countries, assuming the most extreme manifestation of the income elasticity. Within any country, given the slow pace at which inequality typically evolves even with the most extreme known income elasticity and reduction in country inequality, greenhouse gas emissions would increase by less than 8% over a couple of decades. However, when one considers a more equitable distribution of growth between countries, global emissions growth may decrease when compared to growth that occurs in industrialized countries. This is because poorer countries have more potential for technological advancements that reduce the energy intensity of growth than richer countries do. That is, more income growth in poorer countries provides more opportunity for efficiency improvements that influence the emissions of very large populations. Furthermore, China is a poor model for poor countries at large, many of which have relatively low energy intensities, even today.

Climate stabilization at the level aspired to by the Paris Climate Agreement requires that we (i.e. the world) decarbonize to zero annual emissions around 2050, which means that even developing countries have to make aggressive strides towards integrating climate goals into development. Nevertheless, there is no sufficient basis for considering that equitable growth, and by implication the poor’s energy intensity, is part of the problem. To the contrary, the potential for co-benefits from equitable growth for climate change are enormous, but unfortunately under-explored, particularly in quantitative studies. Research should focus on quantifying the role of changing social norms – less consumerism, political mobilization, and other social changes that are typically associated with lower inequality – on reducing greenhouse gases.

Reference:

Rao, ND, Min J. Less global inequality can improve climate outcomes. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change. 2018;e513. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.513

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 14, 2017 | Climate Change, Risk and resilience

By Thomas Schinko, research scholar in the IIASA Risk and Resilience Program.

The hurricanes that swept across the Atlantic in the last few months had terrifying, and in Irma’s case record-breaking, power. They flattened homes and destroyed electricity grids, flooded schools and even threatened the integrity of whole nations. Could some of that immense power provide the impetus we need to switch from talking about climate-related risks and damages to doing something about them proactively?

On top of the hurricanes, in just the last two months the world has seen major flooding in Asia, and scorching heatwaves in southern Europe. While climate-related risks are shaped by many factors, the science shows that climate change is loading the dice, making certain extreme events more likely, and providing more favorable conditions for their formation.

Many are pessimistic about our abilities or inclination to heed the wake-up call. They worry that current political divisions and governance structures will leave us dead in the water.

I have hope. I have been working with colleagues on a way forward on managing climate-related risks that defuses the political nature of the debate and helps forging a stakeholder compromise. At all governance levels and all across the globe, disaster risk management has a long and proven track record for dealing with climate-related and other geophysical extremes, such as earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. This established and politically uncontroversial setting is the point of departure for the concept of ‘climate risk management’. This new concept aims to deal with disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation at the same time, providing a way to circumvent the political hurdles and strengthen global ambitions to tackle climate-related risks.

Aligning climate change adaptation and disaster risk management

In the medium to long term, climate change and adaptation must be incorporated into all kinds and levels of decision and policy making. We can achieve this by increasing understanding of the risks of climate change, and adjusting policy and practice over time according to the latest knowledge and expertise. The importance of climate change is already being recognized in diverse decisions and policies. Just recently, for example, Hong Kong Airport announced that the project to build a third runway incorporated sea level rise projections by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and based on that will include the construction of a sea wall, standing at least 21 feet above the waterline.

Broad stakeholder participation

Putting climate risk management into practice requires balancing the perceptions of climate-related risks of all involved. This calls for a process that involves the participation of those in politics, public administration, civil society, private sector and research.

Putting climate risk management into practice requires balancing the perceptions of climate-related risks of all involved. © Aleksandr Simonov

This may sound excessively time consuming, or even impossible, but it’s not. I know that because I am involved in helping to apply climate risk management in the context of flood risk in Austria. We are only just embarking on the process, and it is lengthy, involving extensive collaboration with relevant ministries, departments, and the private sector—such as insurance companies—but ultimately it can help to co-create a strong policy for the future.

Despite considerable uncertainties in establishing a strong causal link to anthropogenic climate change as risk driver, by employing climate-relevant science to decision making on existing short-term risks we were able to kick-start a process to act on flood risk in the country. This includes critically reflecting on existing policy tools, such as the Austrian disaster fund, and injecting aspects of climate-related risk into long-term budget planning processes.

New solutions to tackle increasing levels of climate risk

As risks increase, however, moving beyond incremental adjustments of existing policy tools is imperative, and totally new solutions will have to be found. Tackling erosive and existential climate-related risks, which lead to the complete loss of people’s and communities’ livelihoods, would require truly transformational action. Such risks are currently discussed under the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage associated with Climate Change Impacts, which was established in 2013 at the 19th Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

For the case of increasingly intolerable flood risk this could mean that in the future raising dikes might not suffice and governments may need to start supporting alternative livelihoods (for example, switching from farming to services sectors); providing climate-resilient social protection schemes; or assisting with voluntary migration. This requires climate risk management to be a learning process itself; flexible towards adjusting to any ecological, societal or political transformations.

Towards transformational climate risk management

To tackle the substantial challenges imposed by increasing climate-related risks, truly transformational thinking is needed. By accounting for underlying socioeconomic and climate-related drivers of risk, as well as for different stakeholder perceptions, climate risk management allows compromises to be achieved that translate into concrete but adaptable action.

Assam Integrated Flood and Riverbank Erosion Risk Management Investment Program in India. © Asian Development Bank

Transformational thinking requires reframing of the overall problem over time. Reframing, in this context, refers to a change in the collective view on climate-related risks and how to tackle those. Taking again flood risk as a case in point, comprehensive flood risk management plans that are based on broad stakeholder participation processes and that allow for adaptive updates over time could be created. In the short term, re-evaluating existing measures may lead to an incremental adjustment of existing flood risk management efforts. The transformative notion comes in over time via proactively discussing trends in climate-related risks, which might eventually lead to the design of new policies and implementation measures, potentially also requiring alternative governance structures.

What is needed next is to provide space and resources for putting climate risk management processes, such as outlined here, into action. It would be a wise decision to seize the historic chance provided by the current alertness to the issue and start taking proactive action on today’s and future losses and damages due to climate-related risks.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 22, 2017 | Climate Change, Environment, Postdoc

By Katya Perez Guzman, IIASA CONACYT postdoctoral fellow in the Advanced Systems Analysis Program

Extractivism, a mode of economic growth currently practiced by many developing countries, is the phenomenon of extracting natural resources from the Earth to sell as raw materials on the world market. It is a central cause of many environmental problems, such as deforestation, loss of habitat and biodiversity, water, soil, and air pollution. Any study of these topics is therefore incomplete if it does not take this model of development into account.

Climate change is no exception, and it is my goal at IIASA to investigate the links between extractivism and climate change mitigation policies for Mexico. To start this search, it is relevant to ask whether the drivers of CO2 emissions might be different in countries that practice extractivism to those that do not. During my PhD, which examined the basic drivers of CO2 emissions in Mexico as a fossil fuel producer and exporter, I suggested that the answer is yes.

Even when there are as many causes of CO2 emissions as there are economic activities, CO2 emissions can be linked to four main drivers: population, GDP per person, the energy use per unit of GDP, and the CO2 emitted by each unit of energy consumed. The greater the value of these variables, and the faster their growth, the more CO2 emissions (all other things being equal). These four factors can then be incorporated into a model known as the Kaya identity, which aims to explain CO2 emissions at a global level.

Deforestation in Malaysia. © Rich Carey | Shutterstock

For fossil fuel producers and exporters, these four elements of the Kaya identity may vary in idiosyncratic patterns across various periods, for example during booms and busts. There is a possible positive relationship between oil abundance and increased population growth, namely because of increased migration to oil production sites. For GDP per capita, a phenomenon known as the natural resource curse describes how production and export of fossil fuels can harm economic growth in the long term, although this debate is still not settled. Alongside this, various analyses have linked fossil fuel production with higher energy consumption, especially during boom times.

Lastly, a proposed carbon curse relates higher abundance of fossil fuels to higher “carbon intensity”—the amount of CO2 emissions per unit of GDP. The carbon curse may be a result of four mechanisms. First, the predominance of a fossil fuel production sector which emits a lot of CO2 itself. Second, crowding out effects in the energy generation sector, forming a barrier to newer renewable energy sources. Third, crowding out effects in other sectors of the economy—a phenomenon known as the “Dutch Disease” because when the Netherlands discovered its Groningen gas field in 1959 the economic boom that followed the gas exports resulted in a decline in manufacturing and agriculture. Finally, less investment in energy efficiency technologies and more subsidies for national fossil fuel consumption can also bring on the carbon curse.

It is therefore crucial to account for the links between extractivism and climate change related topics: for mitigation, but just as importantly for vulnerability and adaptation. If the past can be used to shape the future, a measure of the carbon curse could help national and international policymakers to determine how close an oil-extractive economy can get to being a low carbon economy.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.