Aug 30, 2017 | Environment, Food & Water, Young Scientists

By Parul Tewari, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2017

Two things are distinctly noticeable when you meet Cornelius Hirsch—a cheerful smile that rarely leaves his face and the spark in his eyes as he talks about issues close to his heart. The range is quite broad though—from politics and economics to electronic music.

Cornelius Hirsch

After finishing high school, Hirsch decided to travel and explore the world. This paid off quite well. It was during his travels, encompassing Hong Kong, New Zealand, and California, that Hirsch started taking a keen interest in economic and political systems. This sparked his curiosity and helped him decide that he wanted to take up economics for higher studies. Therefore, after completing his masters in agricultural economics, Hirsch applied for a position as a research associate at the Austrian Institute of Economic Research and enrolled in the PhD-program of the Vienna University of Economics and Business to study trade, globalization, and its impact on rural areas. Currently, he is looking at subsidies and tariffs for farmers and the agricultural sector at a global scale.

As part of the 2017 Young Scientists Summer Program at IIASA, Hirsch is digging a little deeper to analyze how foreign direct investments (FDI) in agricultural land operate. “Since 2000, the number of foreign land acquisitions have been growing—governmental or private players buy a lot of land in different countries to produce crops. I was interested in knowing why there are so many of these hotspots in the world— sub-Saharan Africa, Papua New Guinea, Indonesia—why are people investing in these areas?,” says Hirsch.

Farming in one of the large agricultural areas in Indonesia ©CIFOR I Flickr

Increased food demand from a growing world population is leading to an increased rate of investment in agriculture in regions with large stretches of fertile land. That these regions are largely rain-fed make them even more attractive for investors as they save the cost of expensive irrigation services. In fact, Hirsch argues that “the term land-grabbing is misleading. It should actually be water-grabbing as water is the foremost deciding factor—even more important than simply land abundance.”

Some researchers have found an interesting contrast between FDI in traditional sectors, such as manufacturing, and the ones in agricultural land. While investors in the former look for stable institutions and good governmental efficiency, FDI in land deals seems to target regions with less stable institutions. This positive relationship between corruption and FDI is completely counterintuitive. Hirsch says that one reason could be that “sometimes weaker institutions are easier to get through when it comes to such vast amount of lands. A lot of times these deals and contracts are oral and have no written proof—the contracts are not transparent anyway.”

For example in South Sudan, the land and soil conditions seem to be so good that investors aren’t deterred despite conflicts due to corrupt practices or inefficient government agencies.

One of the indigenous communities in Madagascar, a place which is vulnerable to land acquisitions © IamNotUnique I Flickr

One area that often goes unnoticed is the violation of land rights of indigenous communities. If a government body decides to sell land or give out production licenses to investors for leasing the land without consulting the actual community, it is only much later that the affected community finds out that their land has been given away. Left with no land and hence no source of livelihood, these communities are forced to migrate to urban areas.

A strain of concern enters his voice as Hirsch talks about the impact. “Land as big as two times the area of Ecuador has been sold off in the past—but it accounts for a tiny percentage of the global production area.” With rising incomes and greater consumption of meat, a lot of land is used to produce animal feed crops. “This is a very inefficient way of using land,” he says.

During the summer program at IIASA, Hirsch is generating data that will help him look at these deals in detail and analyze the main factors that are taken into consideration before finalizing a land deal. At the moment he is only able to give an overview of land-grabbing at the global level. With more data on the location of the deals he can look at the factors that influence these decisions in the first place such as the proximity between the two countries involved in agricultural investments and the size of their economies.

While there is always huge media coverage when a scandal about these land acquisitions comes out in the open, Hirsch seems determined to dig deeper and uncover the dynamics involved.

About the researcher

Cornelius Hirsch is a research associate at the Austrian Institute of Economics and Research (WIFO). At IIASA he is working under the supervision of Tamas Krisztin and Linda See in the Ecosystems Services and Management Program (ESM).

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 6, 2017 | Risk and resilience

An interdisciplinary research project explores glo-cal entanglements of power and nature in 18th century Vienna

By Verena Winiwarter, Guest Research Scholar, IIASA Risk and Resilience Program, and Professor, Centre for Environmental History, Alpen-Adria-Universitaet Klagenfurt.

Nowadays, rulers turn to primetime TV events to demonstrate their power, be it putting men on the moon, testing missiles, or building walls. When the kings of France, in particular Louis XIV and XV, built Versailles, they had the same goals: To claim their leading role in Europe and make their mastery of nature and their subjects visible for all.

In the 1700s, the Austro-Hungarian Empire had to pull off a comparable feat, in particular as Emperor Charles VI had a huge constitutional problem: His only surviving child, a smart and pretty daughter, was not entitled to the throne. Only men could be emperors of the Holy Roman Empire. So while eventually, an international agreement allowed young Maria Theresia to succeed him, her position was clearly weak and would become contested right after her father’s death.

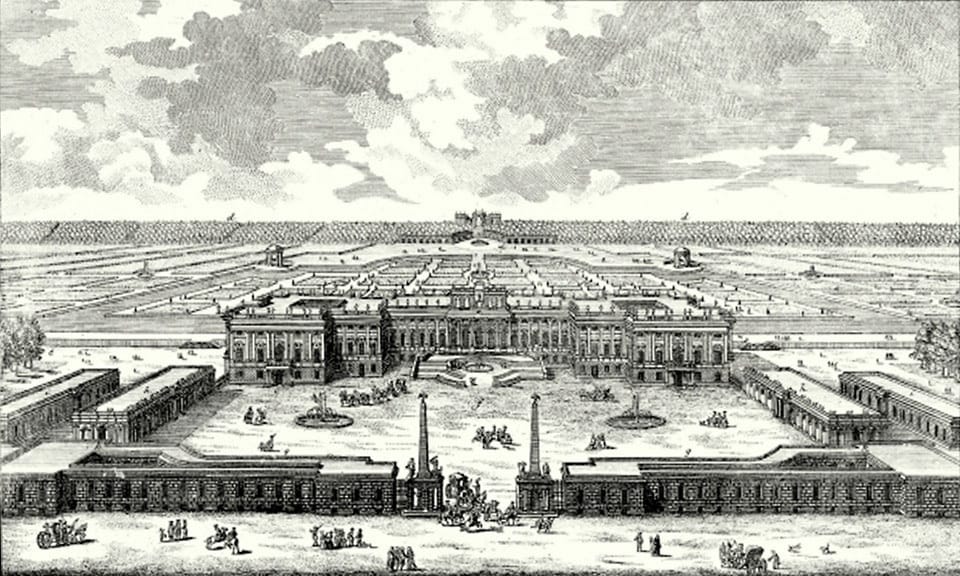

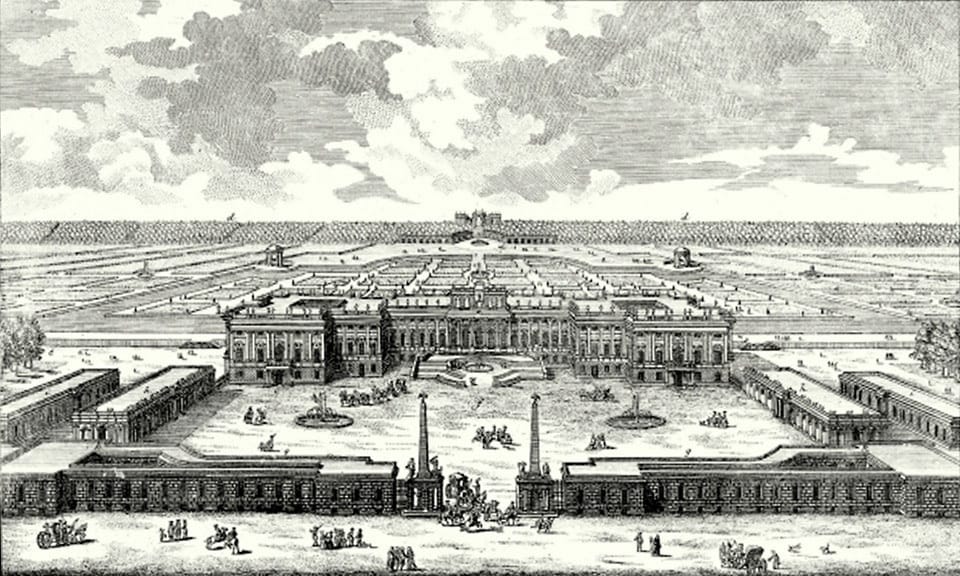

The construction of Vienna’ Schönbrunn Palace, and the taming of the river that flows by it, served as an international declaration of power by the Habsburgs and helped secure Maria Theresia’s position. Vienna, the Habsburg capital, already sported a summer palace in the game-rich riparian area to the west of the city center, close to a torrential, but rather small tributary of the Danube, the Wien River. Here, the leaders decided, a palace dwarfing Versailles should be built. One of the most famous architects of his time, J.B. Fischer von Erlach originally designed a grandiose structure that could never have been carried out. But it staked a claim and when seven years later, a more realistic plan was submitted, it became the actual blueprint of what today is one of Vienna’s most famous tourist sites.

Fischer v. Erlach’s second, more feasible design for Schönbrunn Palace (Public Domain | Wikimedia Commons)

While the kings of France built in a swamp and overcame a dearth of water by irrigation, the Habsburgs’ choice offered another opportunity to show just how absolute their rule was: the torrential Wien River had damaged the walls of the hunting preserve with its then much smaller palace several times. Putting the palace right there, into a dangerous spot, allowed the house of Habsburg to prove that their engineers were in control.

The flamboyant new palace was deliberately placed close to the Wien River, necessitating its local regulation. This had repercussions for those living up- and downstream, as flood regimes changed. Not all such change was beneficial, as constraining the river’s power meant that it found outlets elsewhere. In this case, European power struggles affected the course of a river, putting a strain on locals for the sake of global status.

In the 19th century, effects of global events and structures played out in favor of local health, when it came to building sewers along the by then heavily polluted Wien River. The 1815 eruption of the Tambora volcano in Indonesia led to unusually heavy rains during the otherwise dry season and the proliferation of cholera, which British colonial soldiers brought to Europe. A cholera epidemic hit Vienna in 1831/32, creating momentum to finally build a main sewer along Wien River. The first proposals for a sewer date back to 1792; they were renewed in 1822, but due to urban inertia, the sewer was not built. Thousands of deaths (18,000 in recurring outbreaks between 1831-1873) called for a response, and from 1831 onwards, collection canals were built.

A global constellation had first affected locals negatively, but with long-term positive outcomes of much cleaner water.

We uncovered these stories of the glo-cal repercussions of Wien River management during the FWF-funded project URBWATER (P 25796-G18) at Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt with the joint effort of an interdisciplinary team. We have shown in several publications how urban development was intimately tied to the bigger and smaller surface waters and to groundwater availability, telling a co-evolutionary environmental history.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dhvptRsuJcI

The overall development of the dammed and straightened, then covered river can be seen in science-based videos by team member Severin Hohensinner for 1755. At 2:00 in the video, the virtual flight nears Schönbrunn on the right bank, with the regulation measures visible as red lines. A comparison between 1755 and 2010 is also available. Both videos start with an aerial view of downtown Vienna and then turn to the headwaters of the Wien, progressing towards the center with the flow.

More on the project, including links to publications and images are available at http://www.umweltgeschichte.uni-klu.ac.at/index,6536,URBWATER.html

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jan 28, 2017 | Science and Art

By Gloria Benedikt, IIASA Science and Arts Associate

This post was originally published in the magazine of the 2017 Vienna Science Ball.

Post-truth: the Oxford English Dictionary word of the year 2016 is a paradox for artists and scientists in particular. Post-truth proposes that there has been such a thing as truth in the past. Responsible scientists and artists are – and always have been – on a lifelong journey, driven by curiosity to discover what is not apparent. One group specialized in reason, the other in emotion, they are searching for insights to help society make better informed decisions, knowing that they are only a small part of a truth-searching journey that will continue infinitely. And while scientists try to be as exact as possible, knowing that 100% certainty does not exist, artists strive for perfection all their lives, knowing that perfection does not exist. For both the journey must be the goal. Until recently, this understanding was a fundament on which society could progress. What post-truth really seems to get at is that definite black and white, simple solutions based on instinct are increasingly challenging the nature of science, which is based on ranges and probabilities that are built on knowledge and reason.

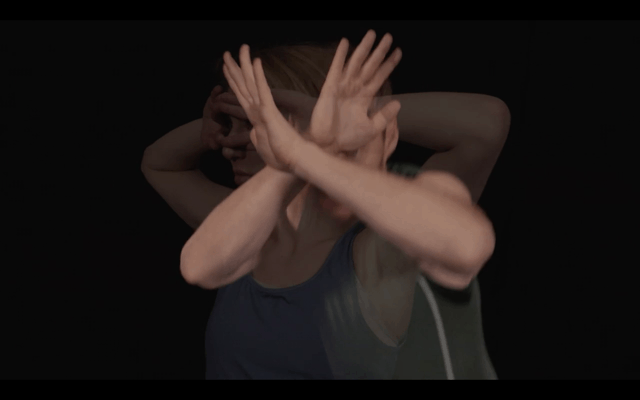

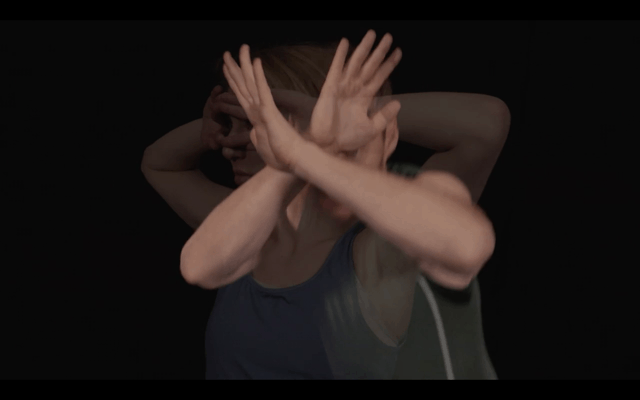

A still from the short film by Gloria Benedikt and Christian Felber ©Patrick Zadrobilek

Public discourse over the causes for this development has increased significantly over the past months, identifying information overload and the loss of gatekeepers due to the digital revolution which seems to be leading people to create their own realities or cognitive ease. I’m confident that many of the problems on the surface, such as the fake news phenomenon will be addressed and solved in the near future. But how can and should science respond and contribute to the underlying issue?

If we are to accept that the new dividing lines appear between ‘rational progressives’ and ‘emotional regressives;’ between those who focus inward and backward, attempting to reject forces of globalization and those who focus outward and forward, embracing the forces of globalization; between those who are overwhelmed by interconnectedness, seeking simple short term solutions, and those willing to work on sustainable long term solutions; between those employing fear and hatred versus those advocating complicated but hopeful solutions,

I believe we need to extend our mission from knowledge production to developing compelling narratives, conveying positive, hopeful solutions that enable people to envision a sustainable future with heart and mind and overcome fear along the way.

This is where artists and scientists can come together, combining their strengths right now: united by the quest to understand how the world works, scientists finding data, artists embedding them in meaning. The short film on post-truth, shown at the Science Ball, is a small step on that journey. It developed out of an artistic urge to respond to the current discourse, which only seemed to touch on the surface of a more fundamental development. To shed light into these depths and find a different response, scientists contributed their views on the issue. Then, there are findings you cannot express with words, and that’s where non-verbal communication comes in. Here the medium is dance.

“Dance is one of the most beautiful forms of cooperation. Verbal language is an inefficient, incomplete form of communication that is prone to misunderstandings. Completing it by the physical, sensual, emotional, intuitive and spiritual spheres will provide a more holistic form of communication,” the economist and dancer Christian Felber observed a while back. He thus was a perfect match in realizing this project. May it now inspire you the audience to contemplate (post) truth from a different angle and the potential of science marrying art along the way.

Watch the full film

Gloria Benedikt is Associate for Science and Art at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA). She is a graduate of the Vienna State Opera Ballet School 01’ and Harvard University 13’.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 13, 2016 | Demography

By Anne Goujon, IIASA World Population Program

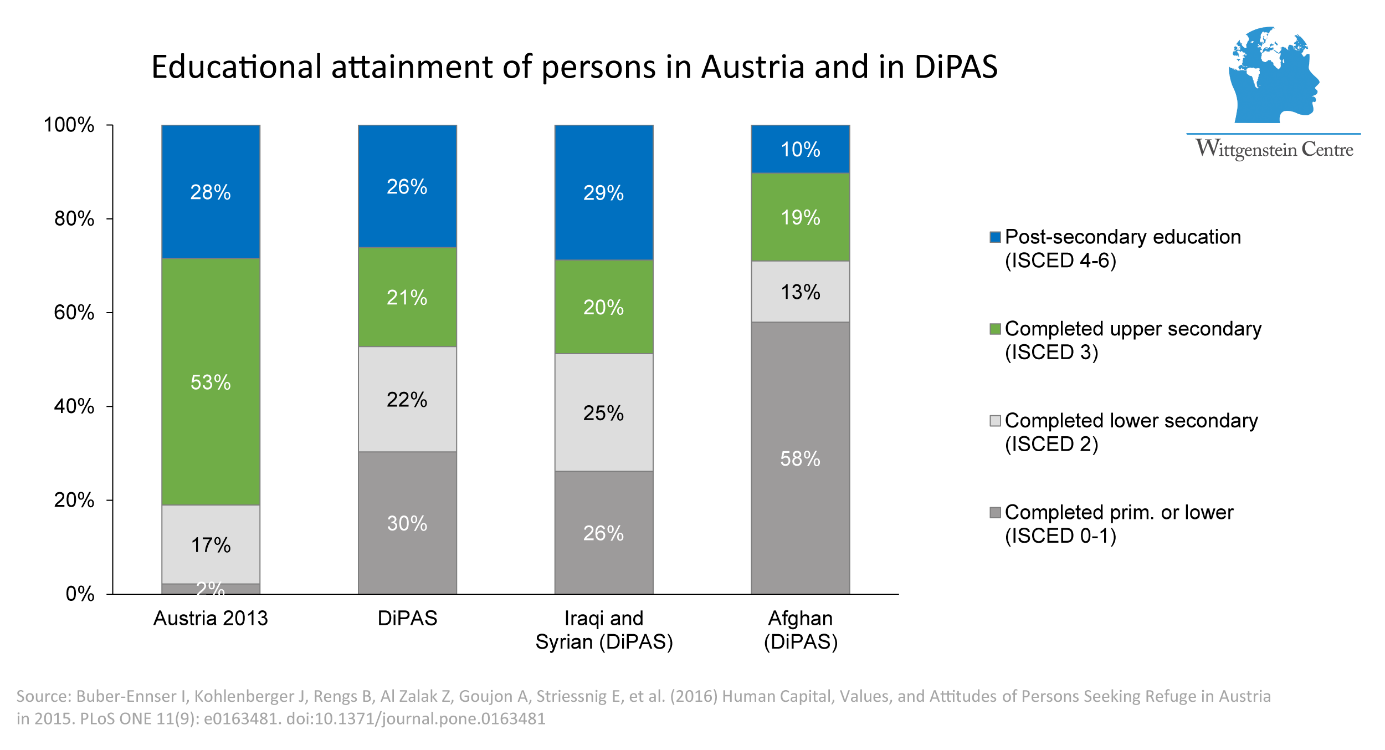

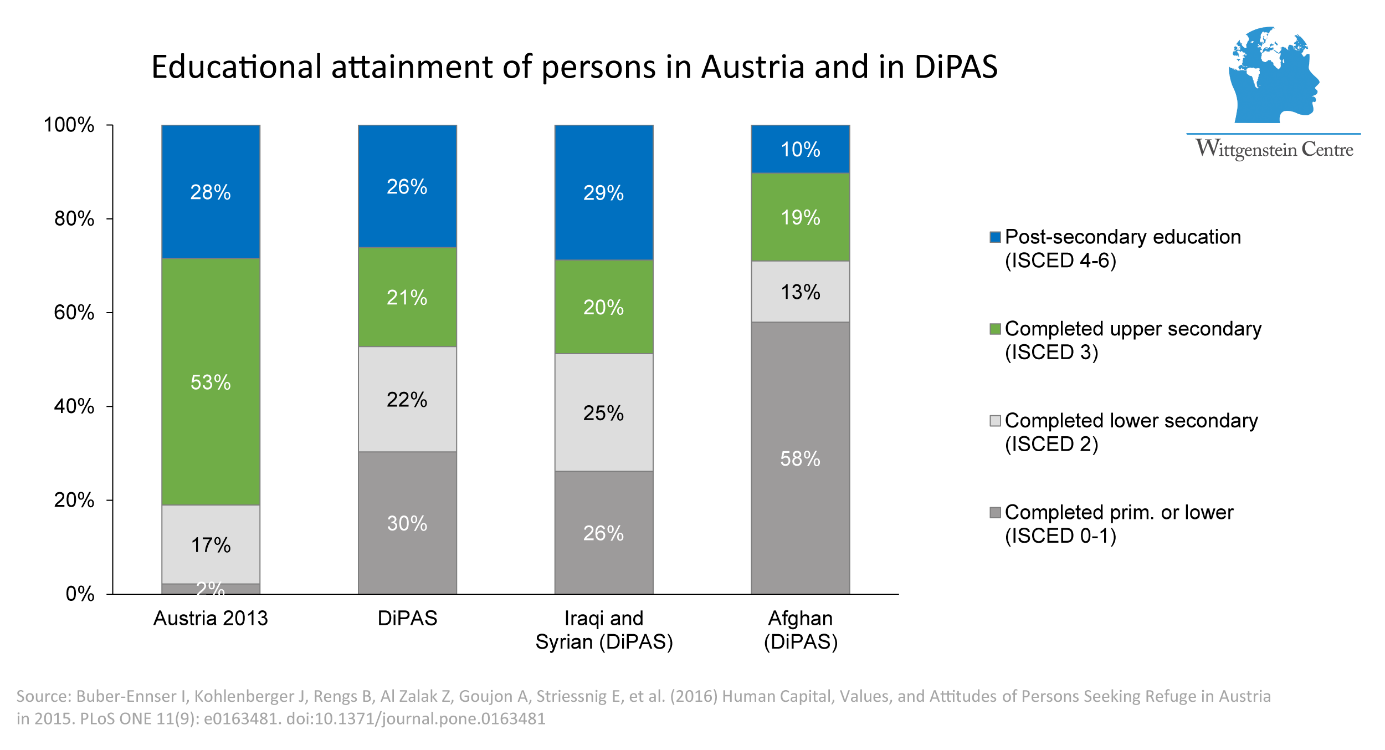

According to the Displaced Persons in Austria Survey (DIPAS) conducted by a team at the Vienna Institute of Demography and at IIASA, the large number of asylum seekers who came to Austria in the fall of 2015 appeared to possess levels of education that are higher than the average level in their country of origins. Moreover, the share of displaced persons from Syria and Iraq with a higher education is close to that of the Austrian population – around 30%.

Students at school in Beirut, Lebanon. Two-thirds of the students at the school are Lebanese and one-third of the students are Syrian. Photo © Dominic Chavez | World Bank

This seemed surprising to many, judging from the number of critical and even aggressive comments that were posted online after the results of this study appeared in PLoS ONE in September and were covered by the press, mostly in Austria. Some of these comments even suggested that people were lying, and/or that the scientists were “do-gooders” covering up the truth.

However, there are several logical reasons for these findings, none of them having anything to do with deceit. The main reason why we know the study participants were not lying is that they had no incentive to lie. They were informed about the purpose of the survey and the fact that there was nothing at stake for them besides contributing to knowledge on the refugee population. Second, their levels of education matched very well with other information they gave, for instance their previous employment, so that if lying, they were uncannily consistent. Moreover, they were rarely alone when taking the questionnaire and it is difficult for a father or mother to lie for instance in front of their children. So we tend to believe the 514 displaced persons that answered the questionnaire. But these are not our only reasons:

Not everyone can afford the adventurous trip to Austria. We asked in the survey how much their journey to Austria–mostly through Turkey–cost, and 75% reported more than 2.000 US$ per person, and 30% more than $4.000. Such a sum is not easy to come by in countries where the average salary is low. The group of asylum seekers that fled to Austria was a selected group with a higher income, and consequently more likely to have had better access to education than those who could not afford to move further and were displaced within Syria or in the neighboring countries (Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan).

Furthermore, this is a young population. Most of them are below the age of 45 years, in fact, the mean age of the respondents was 31 years. Therefore they most likely benefited from the improvements in education that were prevalent in recent times before the war started.

What we cannot say is whether the level of education in their home countries is or was equivalent to the level of education in Austria. For example, we cannot say if an engineer in informatics from the Damascus University has the same knowledge and skills as an engineer trained at the Technical University in Vienna. However, studies implemented by the Public Employment Service in Austria show that refugees’ levels of competence and skills are largely in line with their levels of education and/or occupation. Furthermore, people who successfully pursued a higher education are more likely to be willing and interested to learn new things, such as learning a new language, developing additional skills, or retraining for other professions.

Therefore, the displaced persons that came to Austria at the end of 2015 have a high potential for contributing to the economy that should not be ignored.

Reference

Buber-Ennser, I., Kohlenberger, J., Rengs, B., Al Zalak, Z., Goujon, A., Striessnig, E., Potančoková, M., Gisser, R., Testa, M.R., Lutz, W. (2016) Human Capital, Values, and Attitudes of Persons Seeking Refuge in Austria in 2015. PLoS ONE 11(9): e0163481. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0163481

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 23, 2016 | Science and Art, Science and Policy

Gloria Benedikt was born to dance. She started at the age of three and since the age of 12 she has been training every day—applying the laws of physics to the body. But with a degree in government and an interest in current affairs, Benedikt now builds bridges between these fields to make a difference, as IIASA’s first science and art associate.

Conducted and edited by Anneke Brand, IIASA science communication intern 2016.

Gloria Benedikt © Daniel Dömölky Photography

When and how did you start to connect dance to broader societal questions?

The tipping point was when I was working in the library as an undergraduate student at Harvard University. I had to go to the theater for a performance, and thought to myself: I wish I could stay here, because there is more creativity involved in writing a paper than in going on stage executing the choreography of an abstract ballet. I realized that I had to get out of ballet company life and try to create work that establishes the missing link between ballet and the real world.

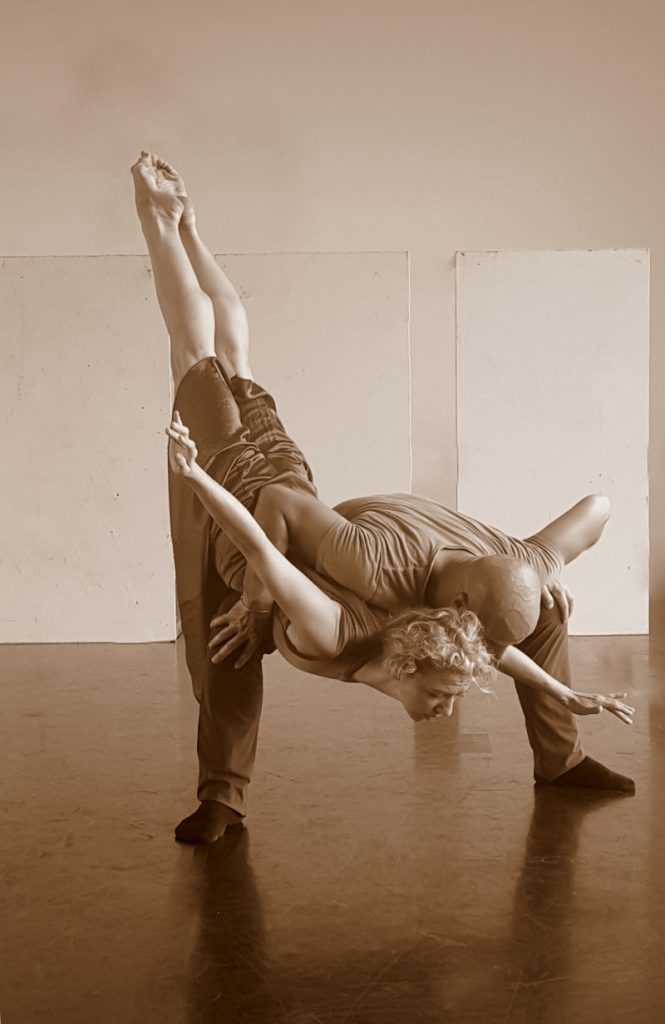

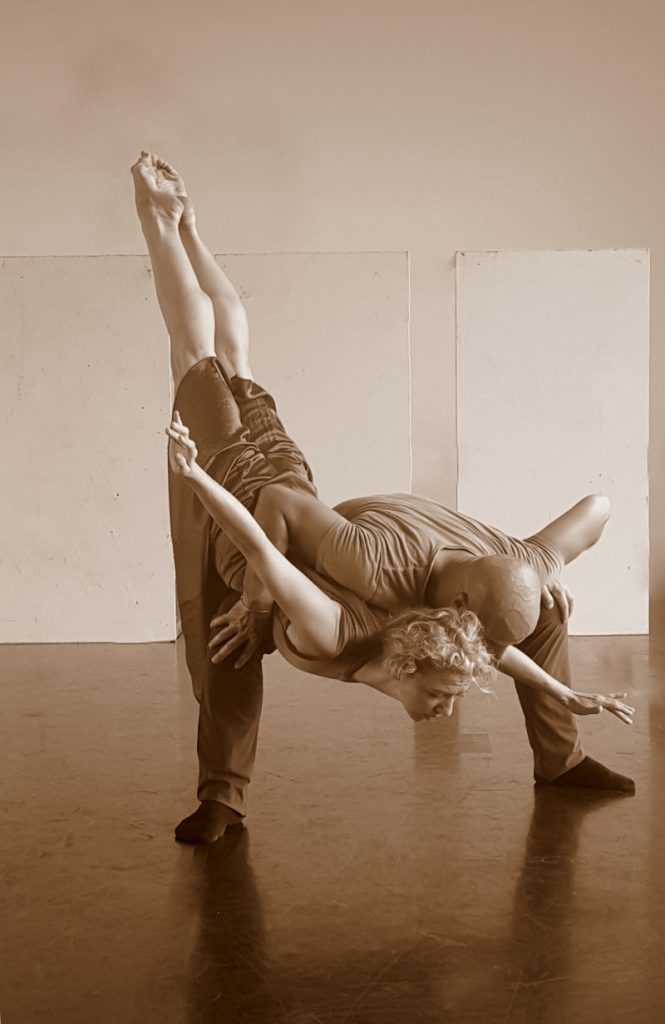

To follow my academic interest, I could write papers, but I had another language that I could use—dance—and I knew that there is a lot of power in this language. So I started choreographing papers that I wrote and rather than publishing them in journals, I performed them. The first work was called Growth, a duet illustrating how our actions on one side of the world impact the other side. As dancers we need to concentrate and listen to each other, take intelligent risks and not let go. If one of us lets go, we would both fall on our faces.

What motivated you make this career change?

We as contemporary artists have to redefine our roles. In recent decades we became very specialized, which is great, but we lost our connection to society. Now it’s time to bring art back into society, where it can create an impact. I am not a scientist. I don’t know exactly how the data is produced, but I can see the results, make sense of it and connect it to the things that I am specialized in.

How did you get involved with IIASA?

I first started interdisciplinary thinking with the economist Tomáš Sedláček who I met at the European Culture Forum 2013. A year later I had a public debate with Tomáš and the composer Merlijn Twaalfhoven in Vienna. Pavel Kabat, IIASA Director General and CEO, attended this and invited me to come to IIASA.

What have you done at IIASA so far?

For the first year at IIASA I created a variety of works to reach out to scientists and policymakers and with every work I went a step further. This year, for the first time I tried to integrate the two groups by actively involving scientists in the creation process. The result, COURAGE, an interdisciplinary performance debate will premiere at the European Forum Alpbach 2016. In September, I will co-direct a new project called Citizen Artist Incubator at IIASA, for performing artists who aim to apply artistic innovation to real-world problems.

Gloria and Mimmo Miccolis performing Enlightenment 2.0 at the EU-JRC. The piece was specifically created for policymakers. It combined text, dance, and music, and reflected on art, science, climate change, migration and the role of Europe in it. © Ino Lucia

How do scientists react to your work?

The response to my performances at the European Forum Alpbach 2015 and the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (EU-JRC) was extremely positive. It was amazing to see how people reacted—some even in tears. Afterwards they said that they didn’t understand what I was trying to say for the past two days, but the moment that they saw the piece, they got it. Of course people are skeptical at first—if they were not, I will not be able to make a difference.

Gloria and Mimmo Miccolis rehearsing at Festspielhaus St. Pölten for COURAGE which will premiere at the European Forum Alpbach 2016.

What are you trying to achieve?

I’m trying to figure out how to connect the knowledge of art and science so that we can tackle the problems we face more efficiently. There are multiple dimensions to it. One is trying to figure out how we can communicate science better. Can we appeal to reason and emotion at the same time to win over hearts and minds?

As dancers we can physically illustrate scientific findings. For instance, in order to perform certain complicated movements, timing is extremely critical. The same goes for implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Are you planning on doing research of your own?

At the moment I am trying something, evaluating the results, and seeing what can be improved, so in a way that is a type of research. For instance, some preliminary results came from the creation of COURAGE. We found that if we as scientists and artists want to work together, both parties will have to compromise, operate beyond our comfort zones, trust each other, and above all keep our audience at heart. That is exactly what we expect humanity to do when tackling global challenges. We have to be team players. It’s like putting a performance on stage. Everyone has to work together.

More information about Gloria Benedikt:

Benedikt trained at the Vienna state Opera Ballet School, and has a Bachelor’s degree in Liberal Arts from Harvard University, where she also danced for the Jose Mateo Ballet Theater. Her latest works created at IIASA will be performed at the European Forum Alpbach 2016 as well as the International Conference on Sustainable Development in New York.

www.gloriabenedikt.com

Fulfilling the Enlightenment dream: Arts and science complementing each other

Note: This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.