Mar 21, 2017 | Climate Change, Energy & Climate, Science and Policy, Young Scientists

By Jessica Jewell, IIASA Energy Program

Why have Germany and Japan, two large, and in many respects similar developed democracies pursued different energy options? A recently published study examines why Germany has become the world’s leader in renewable energy while phasing out its nuclear power and Japan has deployed only a trivial amount of renewables while constructing a record number of nuclear reactors.

The widespread story is that Germany rejected nuclear power in a politically bold move after Fukushima and instead pursued ‘Energiewende’ prioritizing wind and solar energy to combat climate change. Leading scholars such as Amory Lovins described Japanese policymakers as manipulated by the nuclear lobby, clinging to their old ways, and unwilling to properly support renewable energy. The lesson to other countries is that public anti-nuclear sentiments and a capable democratic government is what it takes to turn to decentralized renewable energy.

This research shows that these stories are myths. As I and my coauthor wrote in a letter to the editor in Nature last year, Japan had ambitious renewable targets already before Fukushima and there is no evidence that these have been affected by its nuclear plans. The same holds for Germany: its targets for renewable energy were not affected by the change in its nuclear strategy following Fukushima’s disaster in 2011.

© nixki | Shutterstock

In fact, the differences between Germany and Japan started not in 2011 after Fukushima, but some 20 years earlier in the early 1990s when Japan’s electricity consumption was rapidly growing and it desperately needed to expand electricity generation to feed demand that could not be matched with very scarce domestic fossil fuels. Furthermore, Japan was developing ‘energy angst’ related not only to its high dependence on Middle Eastern oil and gas but also to potential competition with China’s with its rising appetite for energy. At the same time, Germany’s electricity consumption stagnated in the 1990s and its energy security improved following the end of the Cold War. Germany was also one of the world’s largest coal producers and could in principle supply all its domestic electricity from coal. As a result, in the 1990s, Japan was forced to build nuclear power plants, but Germany could easily do without them.

There was another important development in the early 1990s: wind power technology diffused to Germany from neighboring Denmark. This was triggered by an electricity feed-in-law of 1990s, which obliged German electric utilities to buy electricity from small producers at close-to-retail prices. The law, which aimed to benefit a small number of micro-hydro plant owners, unexpectedly led to almost a 100-fold rise in wind installations in Germany. Although still insignificant in terms of electricity, this development created a large and vocal lobby of owners and manufacturers of wind turbines. In the early 2000s, the wind sector provided less than one-tenth of nuclear electricity but had more jobs than in the nuclear sector. In contrast, Japan’s similar policies of buying wind energy from decentralized producers did not result in any considerable growth of wind power, because the Danish technologies prevalent in the early 1990s could not be as easily diffused to Japan.

By the turn of the century, the electricity sectors in Germany and Japan still looked largely similar, but the political dynamics could not be more different. In Germany, a huge politically-powerful coal sector was represented by Socio-Democratic Party and the so-called ‘red-green’ coalition was formed with the Green party, who represented the rapidly growing wind power sector. The stagnating nuclear industry, however, had not seen new domestic orders or construction for 15 years and large industrial players like Siemens had begun to diversify away from it. All this was in the context of a positive energy security outlook and declining electricity prices. In contrast, in Japan, the nuclear sector had vigorously grown over the last decade and was becoming globally dominant by acquiring significant manufacturing capacities. Nuclear power was the only plausible response to the energy angst and it lacked any credible political opponents: the domestic coal sector in Japan virtually did not exist (Germany had around 70,000 coal mining jobs, Japan – about 1,000) and wind had never taken off.

© Pla2na | Shutterstock

The results of these very different political dynamics were predictably different: the red-green coalition in Germany legislated nuclear phase-out in 2002 and unprecedented financial support for renewables in 2000, while retaining coal subsidies and triggering construction of new coal power plants. Japan continued to support solar energy in which it had been the global leader since the 1970s but it also adopted a plan for constructing many more nuclear reactors designed to substitute imported fuels. Fukushima, rather than highlighting differences actually made the energy trajectories of two countries more similar as both countries began to struggle to replace their aging nuclear capacities with new renewables.

How does this story relate to wider questions such as: why are some countries more successful in deploying renewables than others? The answer is not in ‘stronger political will’ and in the strength of climate change concerns, but in economy, geography, and the structure of energy systems. Political wins for renewables and the climate can also be the result of dubious political compromises such as the alliance with the coal lobby in Germany, which led to the rapid growth of renewables and demise of nuclear power. It may be particularly difficult for countries with fossil fuel resources to implement renewable energy policies if they lead to the contraction of domestic coal, gas or oil industries.

Reference: Cherp A, Vinichenko V, Jewell J, Suzuki M, & Antal M (2016). Comparing electricity transitions: A historical analysis of nuclear, wind and solar power in Germany and Japan. Energy Policy 101: 612-628.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the CD-LINKS project and the Central European University’s Intellectual Theme’s Initiative.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 23, 2016 | Science and Art, Science and Policy

Gloria Benedikt was born to dance. She started at the age of three and since the age of 12 she has been training every day—applying the laws of physics to the body. But with a degree in government and an interest in current affairs, Benedikt now builds bridges between these fields to make a difference, as IIASA’s first science and art associate.

Conducted and edited by Anneke Brand, IIASA science communication intern 2016.

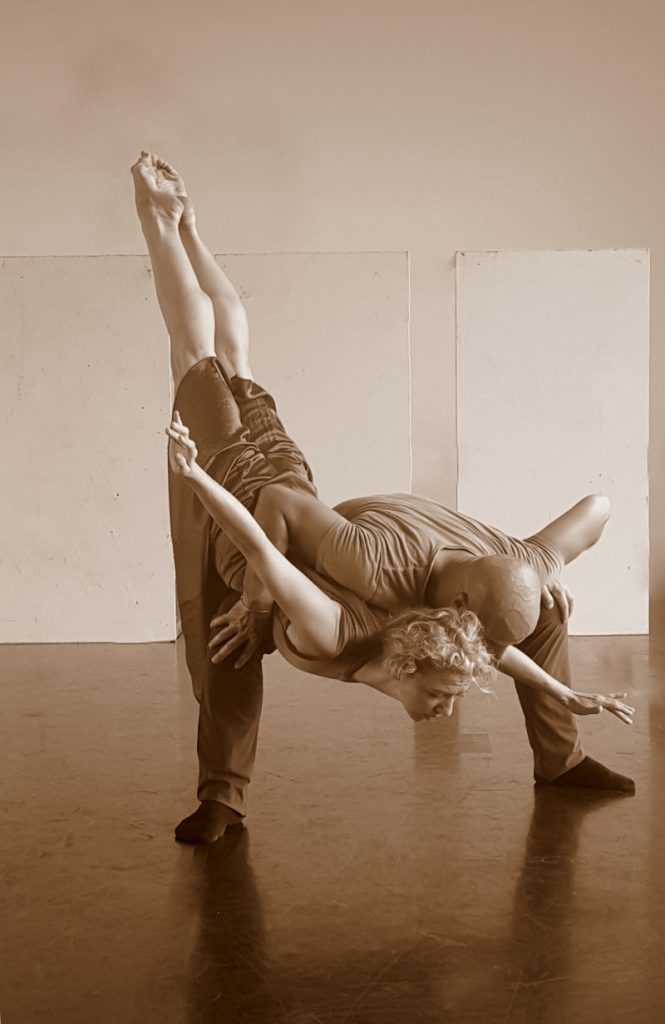

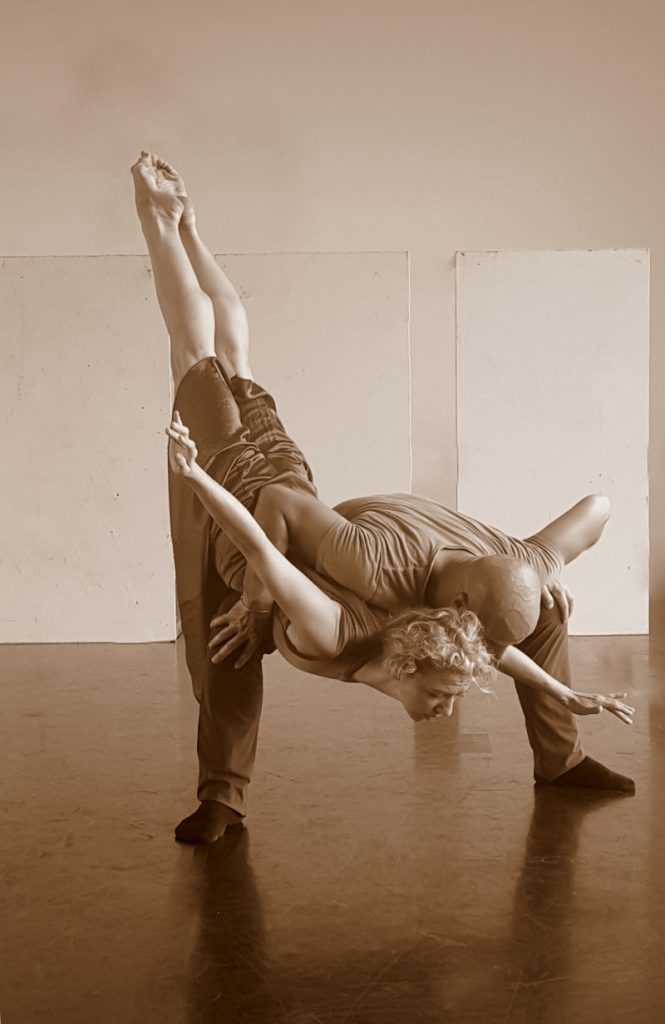

Gloria Benedikt © Daniel Dömölky Photography

When and how did you start to connect dance to broader societal questions?

The tipping point was when I was working in the library as an undergraduate student at Harvard University. I had to go to the theater for a performance, and thought to myself: I wish I could stay here, because there is more creativity involved in writing a paper than in going on stage executing the choreography of an abstract ballet. I realized that I had to get out of ballet company life and try to create work that establishes the missing link between ballet and the real world.

To follow my academic interest, I could write papers, but I had another language that I could use—dance—and I knew that there is a lot of power in this language. So I started choreographing papers that I wrote and rather than publishing them in journals, I performed them. The first work was called Growth, a duet illustrating how our actions on one side of the world impact the other side. As dancers we need to concentrate and listen to each other, take intelligent risks and not let go. If one of us lets go, we would both fall on our faces.

What motivated you make this career change?

We as contemporary artists have to redefine our roles. In recent decades we became very specialized, which is great, but we lost our connection to society. Now it’s time to bring art back into society, where it can create an impact. I am not a scientist. I don’t know exactly how the data is produced, but I can see the results, make sense of it and connect it to the things that I am specialized in.

How did you get involved with IIASA?

I first started interdisciplinary thinking with the economist Tomáš Sedláček who I met at the European Culture Forum 2013. A year later I had a public debate with Tomáš and the composer Merlijn Twaalfhoven in Vienna. Pavel Kabat, IIASA Director General and CEO, attended this and invited me to come to IIASA.

What have you done at IIASA so far?

For the first year at IIASA I created a variety of works to reach out to scientists and policymakers and with every work I went a step further. This year, for the first time I tried to integrate the two groups by actively involving scientists in the creation process. The result, COURAGE, an interdisciplinary performance debate will premiere at the European Forum Alpbach 2016. In September, I will co-direct a new project called Citizen Artist Incubator at IIASA, for performing artists who aim to apply artistic innovation to real-world problems.

Gloria and Mimmo Miccolis performing Enlightenment 2.0 at the EU-JRC. The piece was specifically created for policymakers. It combined text, dance, and music, and reflected on art, science, climate change, migration and the role of Europe in it. © Ino Lucia

How do scientists react to your work?

The response to my performances at the European Forum Alpbach 2015 and the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (EU-JRC) was extremely positive. It was amazing to see how people reacted—some even in tears. Afterwards they said that they didn’t understand what I was trying to say for the past two days, but the moment that they saw the piece, they got it. Of course people are skeptical at first—if they were not, I will not be able to make a difference.

Gloria and Mimmo Miccolis rehearsing at Festspielhaus St. Pölten for COURAGE which will premiere at the European Forum Alpbach 2016.

What are you trying to achieve?

I’m trying to figure out how to connect the knowledge of art and science so that we can tackle the problems we face more efficiently. There are multiple dimensions to it. One is trying to figure out how we can communicate science better. Can we appeal to reason and emotion at the same time to win over hearts and minds?

As dancers we can physically illustrate scientific findings. For instance, in order to perform certain complicated movements, timing is extremely critical. The same goes for implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Are you planning on doing research of your own?

At the moment I am trying something, evaluating the results, and seeing what can be improved, so in a way that is a type of research. For instance, some preliminary results came from the creation of COURAGE. We found that if we as scientists and artists want to work together, both parties will have to compromise, operate beyond our comfort zones, trust each other, and above all keep our audience at heart. That is exactly what we expect humanity to do when tackling global challenges. We have to be team players. It’s like putting a performance on stage. Everyone has to work together.

More information about Gloria Benedikt:

Benedikt trained at the Vienna state Opera Ballet School, and has a Bachelor’s degree in Liberal Arts from Harvard University, where she also danced for the Jose Mateo Ballet Theater. Her latest works created at IIASA will be performed at the European Forum Alpbach 2016 as well as the International Conference on Sustainable Development in New York.

www.gloriabenedikt.com

Fulfilling the Enlightenment dream: Arts and science complementing each other

Note: This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 19, 2016 | Science and Policy, Young Scientists

By Anneke Brand, IIASA science communication intern 2016.

For Malgorzata (Gosia) Smieszek it’s all about making sound decisions, and she is not afraid of using unconventional routes in doing so. She applies this rule to various aspects of her fast-paced life. Whether it is taking the right steps in trail running races, skiing or relocating to the Arctic Circle to do a PhD.

Gosia Smieszek © J. Westerlund, Arctic Centre

Gosia’s passion for the Arctic began to evolve during a conversation with a professor at a time when she was contemplating the idea of returning to academia. “I remember, when he said the word Arctic, I thought: yes, that’s what I want to do. True, before I was interested in energy and environmental issues, but the Arctic was certainly not on my radar. So I went to the first bookstore I found, asked for anything about the North and the lady, after giving me a very confused look, said she might have some photo books. So I left with one and things developed from there.”

In 2013 Gosia joined the Arctic Centre of the University of Lapland in Rovaniemi, Finland. Living there is not always easy, but hey, if you get to see the Northern Lights, reindeers and Santa Claus on a regular basis, it might be worth enduring long times of darkness in winter and endless sunshine in summer. With temperatures averaging −30°C, Rovaniemi is the perfect playground for Gosia.

Running is one of Gosia’s favorite sports. She has competed in a few marathons, but her biggest race to date is the Butcher’s Run, an ultra trail of 83km over the Bieszczady mountains in Poland. Here she is running in the Tatra mountains. © Gosia Smieszek

Gosia grew up in Gliwice, a town in southern Poland, before moving to Kraków where she completed her undergraduate degree in international relations and political science. This was just before Poland’s accession to the EU, so it was the perfect time to pursue studies in this field.

She continued her studies in various locations including Belgium, France, Poland, and Austria. Before continuing her education and later working at the College of Europe, she also gained working experience as a translator at a large printing house in her home town in Poland.

For her PhD Gosia focuses on the interactions between scientists and policymakers, with the aim of enhancing evidence-based decision making in the Arctic Council. Scientific research on the Arctic has been conducted for decades, but “when it comes to translating science into practice it is still a huge challenge―on all possible levels,” she says.

“Scientists and policymakers have their own, very different, universes—with their own stories, goals, timelines, working methods and standards. It is better than in the past, but still extremely difficult to make these two universes meet.”

Gosia with fellow YSSPers, Dina, Stephanie and Chibulu during a visit to Hallstadt. © Chibulu Luo

As part of the Arctic Futures Initiative at IIASA, Gosia investigates and maps the structural organization of the Arctic Council and aims to determine the effectiveness of interactions between scientists and policymakers, as well as ways to improve the flow of knowledge and information between them.

Because of the nature of her work, Gosia spends almost half her time away from home, but you will never find her traveling without running shoes, swimming gear, and something to read. Diving, one of her greatest passions, has taken her to amazing places like Cuba and the Maldives, where meeting a whale shark face-to-face topped her list of underwater experiences.

Gosia swimming with a whale shark. © Eiko Gramlich

Gosia is truly hoping to make a difference with her research on science-policy interface. She says: “To me, trying to bridge science and policy is a truly fascinating endeavor. Exploring these two worlds, seeking to understand them and learning their ‘languages’ to enable better communication between them is what drives me in my research. So hopefully we can learn from past mistakes and make things better—this time.”

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Mar 1, 2016 | Communication, Science and Policy

By IIASA Science Writer and Editor Daisy Brickhill.

“The thing about communicating science today is…people can always watch cat videos instead. And let’s face it, some of those clips are really funny.”

Marshall Shepherd, former president of the American Meteorological Society, smiles at the audience of this science communication seminar, aware of the frustrated sighs going on in the room, and in some cases the blank incredulity—people wouldn’t watch cat videos when they could be paying attention to my science, surely?

We are at the AAAS annual meeting, a vast conference with around 10,000 attendees from all walks of life, from toddlers to retired professors. The science presented here is truly diverse, and covers everything from radically successful new cancer treatments, to advances in artificial intelligence, to the IIASA session on how we can hope to achieve all 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Shepherd is speaking of his long career engaging with the public about his work on weather systems and climate change. “Get out of your ivory tower,” he urges all researchers. There are important issues at stake, and what if no one speaks for the scientific evidence?

However, communicating science effectively is not easy. Understanding something does not mean you are automatically good at explaining it. All through academic training researchers learn how to speak to people in their own field, who talk just like them. That’s important, they might be your next reviewer, after all. But it is only one, narrow form; engaging the public requires a high level of understanding, not just of the topic, but of the audience and communication itself.

“We have left behind the old idea of science communication where brains are empty vessels waiting to be filled,” says the next speaker, Barbara Klein Pope, executive director for communications for the National Academies. “They are a swamp, and we need to explore that swamp to communicate properly.” She describes research which tested the effects of different types of communication on people’s perceptions of social science, in terms of whether they felt it was worth funding, for instance (oh yes, I sense the academic ears pricking up now).

The mind is not an empty vessel waiting to be filled, it’s a swamp to be navigated.

The findings of this work led to a framework of three clear messages. First, use exemplars—a good example can do wonders—yes, your research might be relevant across reams of different cases but general, expansive terms are often vague and a simple example can bring clarity.

Second, the all-important yet surprisingly often neglected question, “Why do we care?” Bear in mind also that it’s not why you care, you’ve made a career out of this science, we know why you care, but why should your audience care.

Finally, use metaphors. Science is often very complex, and pretty much anyone outside your field will need something they can relate to—a familiar concept that they can use to begin to explore the new territory. In case you need more convincing, the use of metaphors was shown to have a significant effect on whether the public felt the work was worth funding.

At the end of that session I was struck by the parallels between this session and another I attended on science-policy interactions with speakers Vladimír Sucha, Daniel Sarewitz, and Peter Gluckman, all working at the forefront of science-policy.

Trust, built on good communication, is vital, the speakers all agreed. Interesting conclusions should not be buried at the end of a report, they should be at the start, just as they would be for the public, and any article or briefing should be kept as short and relevant as possible. Examples and metaphors play a role here too, and a good story with persuasive anecdotes can have much more impact than a dry report.

What not to do, Sucha reminds us, is send an email saying “Here are the links to 200 peer-reviewed papers on this, you’ll find it all there.” After all, policymakers can access cat videos just as easily as the rest of us.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

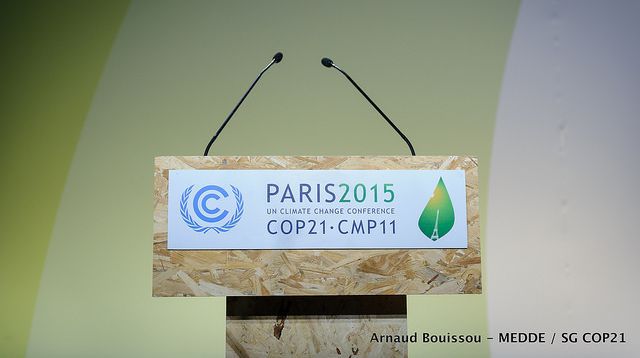

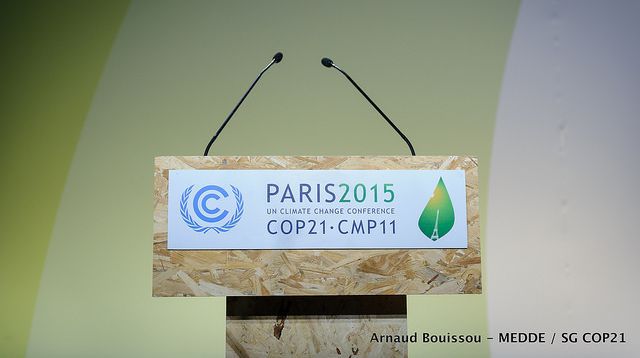

Dec 4, 2015 | Climate Change, Science and Policy

By IIASA Director General and CEO Professor Dr. Pavel Kabat. This article was originally published in the Huffington Post.

I was at the Kyoto climate talks in 1997. I remember doing the calculations, going through the proposals long into the night. I remember the moment of: “We did it. We have an international, legally binding agreement.” I remember the euphoria.

But I also remember what happened after that. As the years passed after Kyoto I saw that the reality of implementation was far from what we had envisaged. As a scientist in the field I took part in many government discussions, and I grew frustrated at the inability of institutions and governments to comply with the agreements.

More than empty promises?

These failures do not mean that Paris will just be the next in a string of ineffective climate talks. A global, UN-level agreement on climate change is necessary, and I believe Paris will deliver it. But I do not see it as providing more than a direction. Yes, we will have an agreement, but our unrelenting focus from Paris onward must be on how to implement it. And that will require a major change in our way of thinking.

Policymakers, climate scientists and society as a whole, must abandon the idea of climate change as a single, discrete issue, to be dealt with using “climate policy.” We cannot think about the future without thinking about climate change. On the other hand, we cannot deal with climate change without considering the future social and economic context. Ultimately, if we do not make climate adaptation and mitigation part of the mainstream development agenda, we will fail again.

Take the Green Climate Fund. An excellent initiative agreed at the 2009 Copenhagen climate talks, it assists developing countries in climate change adaptation. But it is designated as “climate change” money. Let’s say a dike in Bangladesh is being extended, will we advise that only 25 cm of the 40 cm extension be covered by the climate fund because technically that is all that is needed for climate change, and the rest is just “general development”?

Frankly, we shouldn’t care. We shouldn’t spend time or money on such questions. We need an institutional and financial framework within which we are able to say yes, there is a climate objective, but there is also a development objective, and a security objective, together these make up a whole, and we will invest in infrastructure accordingly.

Paris is just the beginning

To ensure that climate change adaptation and mitigation become integral to development, governance also must change. Future strategy cannot consist only of centralized agencies issuing endless targets. Municipalities and small regions have an important part to play. Local efforts will also be more likely to engage people, because they are closer to personal experiences. In fact, while we scientists and politicians talk in dusty rooms, younger generations are already exploring new, bottom-up solutions, such as crowd-funding and joint ownership.

Investment from the private sector is also key. In the Earth Statement, written by an alliance of 17 global-change scientists, including myself, we state that: We must unleash a wave of climate innovation for the global good, and enable universal access to the solutions we already have.

The good news is that at this moment, making the transition to a decarbonized world is still a major opportunity. We can leave behind the idea that we must put aside money to protect our economy against the threat of climate change. Investing in these global transitions can actually be hugely beneficial, both economically and socially. Changing the fundamental narrative of climate change from threat to an opportunity will trigger major innovations and transitions to sustainable economic development.

Climate science must change too. We already know the basic facts. We know that to have at least a 66% chance of keeping the temperature increase below 2°C, our greenhouse gas emissions should drop by 40-70 % between 2010 and 2050.

The next report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and climate research in general, now needs to get at the real issue: implementation. How do we achieve our goals in the institutional, social, and economic context? That is where the main focus should be.

Achieving a stable, sustainable future is possible. If it wasn’t, I would be doing something else with my life. I am convinced that the Paris talks will result in an important, international agreement; but the real solution lies beyond Paris, and beyond the UN altogether. It lies in integrating climate into all development and funding decisions, in giving entrepreneurs and local municipalities the space they need to innovate, and encouraging private investment into climate-friendly development. It is a great opportunity for humanity.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 27, 2015 | Science and Policy

By Tanja Kähkönen, University of Eastern Finland, School of Forest Sciences & Institute for Natural Resources, Environment and Society

This autumn I attended the first joint JRC-IIASA Summer School on Evidence and Policy, which brought together policymakers and early-career scientists like myself to learn about the evidence-policy interface. After intensive days of interacting at lectures, learning together, and sharing views during the breaks, I can really say that as scientists we are operating in a different culture to policymakers.

Discussion and debate fostering greater understanding between researchers and policymakers at the JRC-IIASA summer school

This difference extends not only to what we do in our daily work, but also to what kind of language we use, how we communicate, and what level of certainty we give—or have to give—to the issues that we address. Often as scientists we are so intensively involved in our own work that we forget that communicating our research to policymakers cannot be done in the same way as communication with other researchers. This is because policymakers have different evidence needs, expected timeframes for information production, and level of discipline-specific understanding.

However, despite the different cultures, it is possible to learn to speak each others’ language and communicate more efficiently. Developing this communication was practiced throughout the course and a significant part of this took place during “masterclasses,” given by people who are themselves at the science-policy interface as part of their daily work.

I found the masterclass session on wicked problems and evidence-based policy, run by Jan Staman and Annick de Vries from the Rathenau Institute in the Netherlands, particularly attention-grabbing. They pointed out that apart from crises, for which policymakers need rapid evidence on specific topics, wicked—difficult to solve—problems such as creating climate change policy may face problems of scientific evidence overload, political dead-locks, and societal controversies.

The masterclass on uncertainty, risk and hazard, and the links to policymaking was also particularly eye-opening. Session leaders David Wilkinson and Jutta Thielen of the JRC suggested that a range of scenarios and consequences should be offered to policymakers in order to allow them to take better decisions under uncertain conditions in which risks of human loss or health hazard maybe high.

Other sessions focused on foresight, effective communication, using games for informing public and policy debates (crowdsourcing our search for solutions), big data, randomization, modeling, and the pros and cons of working at the science-policy interface—all very important topics for improving communication between scientists and policymakers.

All in all, I guess the take home messages of this course are different for each participant. As a scientist, the big messages for me came from the wrap up session in which “dos and don’ts” for evidence-informed policymaking were summarized by all the summer school participants. For the “dos” words such as trust, communication, providing clear and concise messages, being certain about something, keeping it simple, and understanding policy processes leapt out at me.

Despite the fact that the summer school lasted only three days, I am positive that it will have a lasting effect on the participants, opening a path for cross-cultural understanding between scientists and policymakers. Together improving communication to the benefit of our changing society.

Participants of the first JRC-IIASA Summer School on Evidence and Policy

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.