Oct 25, 2016 | Science and Art

By Chantal Bilodeau, playwright

This could have been the title of my application to the first Citizen Artist Incubator (CAI) hosted at IIASA September 4-30, 2016. I am a Canadian playwright and research artist based outside of New York City, whose work deeply engages with climate change. For me, IIASA was the ultimate dating pool.

Playrwright Chantal Bilodeau is working on a series of plays about the impact of climate change on the eight countries of the Arctic. Photo courtesy Chantal Bilodeau

My belief in art/science romance was further reinforced when IIASA Director General and CEO Professor Dr. Pavel Kabat told us – thirteen artists from Europe, the Middle-East, Africa and America – during one of our sessions, “You have a big responsibility, my friends.” He was referring to the need for artists to engage with pressing global issues, and help change negative narratives into positive narratives of opportunity and social innovation. Big responsibility, indeed. And all the more reason for artists and scientists to become bedfellows.

I came to IIASA to do research for a play about human and animal migration, set in Alaska. The play is part of a long-term project titled The Arctic Cycle. A series of eight plays that look at the social and environmental changes taking place in the eight countries of the Arctic, The Arctic Cycle seeks to 1) bring attention to the changes happening in the Arctic and the impact those changes are having on local communities; 2) encourage international and multidisciplinary collaboration across Arctic countries, and; 3) translate scientific data into personal stories.

Sila was the first of the eight plays in the Arctic Cycle. it focuses on Canada. Credit: A.R. Sinclair Photography

I wanted to talk to scientists to get information for my play, but also to explore what might be possible. How can we join forces? How can my talent and skills and sphere of influence be combined with yours to create greater impact? I reached out to people in the Arctic Futures Initiative, the World Population program, and the Evolution and Ecology program. In addition to pointed questions about migration I asked questions like: “If there was one thing you would like people to understand about your field that I could communicate through my work, what would it be?” “Are there situations where having an artist’s perspective in addition to a scientist’s perspective would be useful?”

Everyone was extremely generous with their time and graciously answered my questions. I was pleased to find out there is genuine interest in investigating where art and science might intersect. The most obvious intersection, of course, is in “translating” scientific information into works of art that are then presented in traditional venues. But what about other intersections? Could artists facilitate conversations between scientists and stakeholders? Could a play (as I experienced once before) set the tone for an entire conference? What would be the value of having an artist embedded into a scientific program? Or a field trip?

Thanks to Gloria Benedikt, Merlijn Twaalfhoven, and their partners who invited me to participate in CAI, I came away from IIASA with concrete and up-to-date information for my play, and ideas for activities and programs that could bring art and science closer together around issues of climate change. I also left with a few email addresses and phone numbers. I am hoping this may be the beginning of a courtship that will lead to long and meaningful relationships.

Participants in the Citizen Artist Incubator 2016 ©Patrick Zadrobilek

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 23, 2016 | Science and Art, Science and Policy

Gloria Benedikt was born to dance. She started at the age of three and since the age of 12 she has been training every day—applying the laws of physics to the body. But with a degree in government and an interest in current affairs, Benedikt now builds bridges between these fields to make a difference, as IIASA’s first science and art associate.

Conducted and edited by Anneke Brand, IIASA science communication intern 2016.

Gloria Benedikt © Daniel Dömölky Photography

When and how did you start to connect dance to broader societal questions?

The tipping point was when I was working in the library as an undergraduate student at Harvard University. I had to go to the theater for a performance, and thought to myself: I wish I could stay here, because there is more creativity involved in writing a paper than in going on stage executing the choreography of an abstract ballet. I realized that I had to get out of ballet company life and try to create work that establishes the missing link between ballet and the real world.

To follow my academic interest, I could write papers, but I had another language that I could use—dance—and I knew that there is a lot of power in this language. So I started choreographing papers that I wrote and rather than publishing them in journals, I performed them. The first work was called Growth, a duet illustrating how our actions on one side of the world impact the other side. As dancers we need to concentrate and listen to each other, take intelligent risks and not let go. If one of us lets go, we would both fall on our faces.

What motivated you make this career change?

We as contemporary artists have to redefine our roles. In recent decades we became very specialized, which is great, but we lost our connection to society. Now it’s time to bring art back into society, where it can create an impact. I am not a scientist. I don’t know exactly how the data is produced, but I can see the results, make sense of it and connect it to the things that I am specialized in.

How did you get involved with IIASA?

I first started interdisciplinary thinking with the economist Tomáš Sedláček who I met at the European Culture Forum 2013. A year later I had a public debate with Tomáš and the composer Merlijn Twaalfhoven in Vienna. Pavel Kabat, IIASA Director General and CEO, attended this and invited me to come to IIASA.

What have you done at IIASA so far?

For the first year at IIASA I created a variety of works to reach out to scientists and policymakers and with every work I went a step further. This year, for the first time I tried to integrate the two groups by actively involving scientists in the creation process. The result, COURAGE, an interdisciplinary performance debate will premiere at the European Forum Alpbach 2016. In September, I will co-direct a new project called Citizen Artist Incubator at IIASA, for performing artists who aim to apply artistic innovation to real-world problems.

Gloria and Mimmo Miccolis performing Enlightenment 2.0 at the EU-JRC. The piece was specifically created for policymakers. It combined text, dance, and music, and reflected on art, science, climate change, migration and the role of Europe in it. © Ino Lucia

How do scientists react to your work?

The response to my performances at the European Forum Alpbach 2015 and the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (EU-JRC) was extremely positive. It was amazing to see how people reacted—some even in tears. Afterwards they said that they didn’t understand what I was trying to say for the past two days, but the moment that they saw the piece, they got it. Of course people are skeptical at first—if they were not, I will not be able to make a difference.

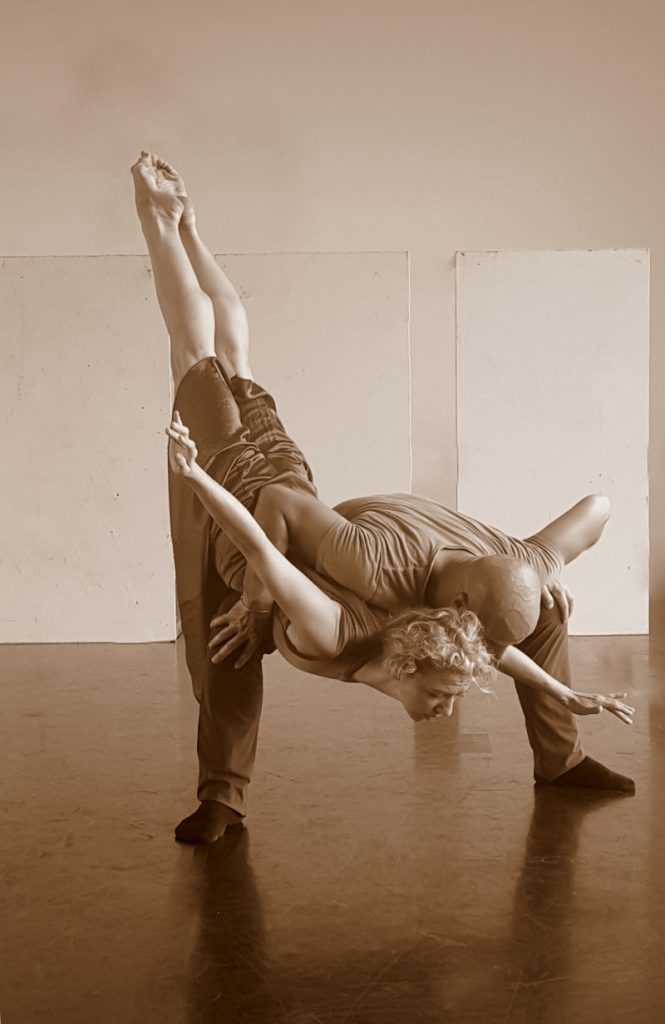

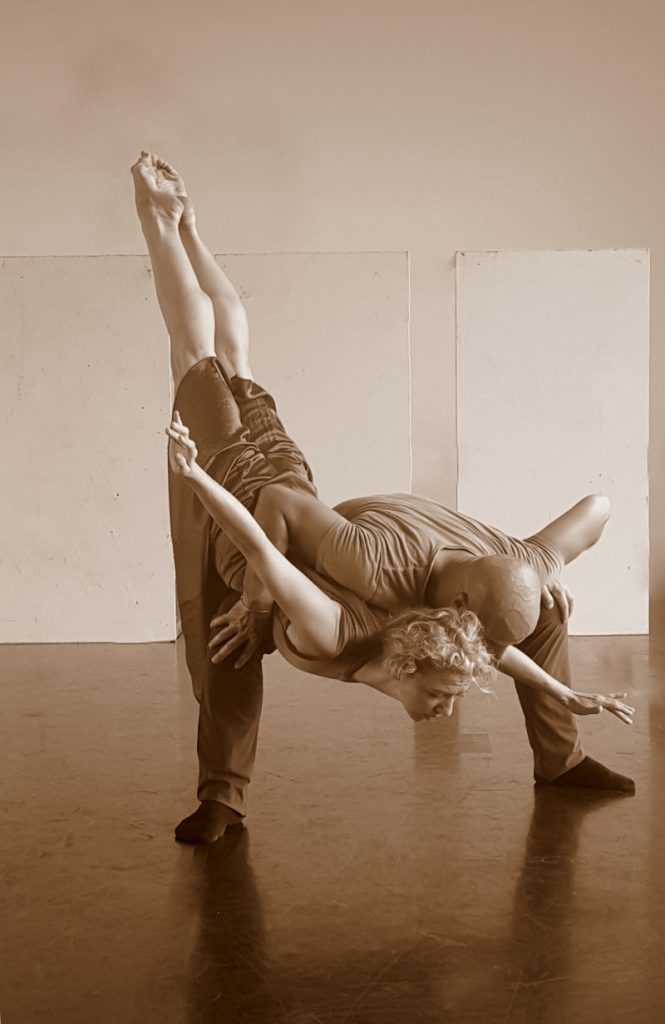

Gloria and Mimmo Miccolis rehearsing at Festspielhaus St. Pölten for COURAGE which will premiere at the European Forum Alpbach 2016.

What are you trying to achieve?

I’m trying to figure out how to connect the knowledge of art and science so that we can tackle the problems we face more efficiently. There are multiple dimensions to it. One is trying to figure out how we can communicate science better. Can we appeal to reason and emotion at the same time to win over hearts and minds?

As dancers we can physically illustrate scientific findings. For instance, in order to perform certain complicated movements, timing is extremely critical. The same goes for implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Are you planning on doing research of your own?

At the moment I am trying something, evaluating the results, and seeing what can be improved, so in a way that is a type of research. For instance, some preliminary results came from the creation of COURAGE. We found that if we as scientists and artists want to work together, both parties will have to compromise, operate beyond our comfort zones, trust each other, and above all keep our audience at heart. That is exactly what we expect humanity to do when tackling global challenges. We have to be team players. It’s like putting a performance on stage. Everyone has to work together.

More information about Gloria Benedikt:

Benedikt trained at the Vienna state Opera Ballet School, and has a Bachelor’s degree in Liberal Arts from Harvard University, where she also danced for the Jose Mateo Ballet Theater. Her latest works created at IIASA will be performed at the European Forum Alpbach 2016 as well as the International Conference on Sustainable Development in New York.

www.gloriabenedikt.com

Fulfilling the Enlightenment dream: Arts and science complementing each other

Note: This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 1, 2016 | Communication, IIASA Network, Science and Art

Known to the world as a metropolis of music the science in Vienna does not receive the recognition and international visibility its excellence deserves. To change this would require not so much more money but a new mindset, agree two prominent players in scientific research in Vienna: Director General and CEO of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) Professor Dr. Pavel Kabat and President of the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (IST Austria) Dr. Thomas Henzinger.

How does Vienna and its scientific research community benefit from the presence of the two institutions and vice versa?

Henzinger: Vienna is a hub for scientific research in Europe. There are a number of universities and institutions in Vienna and they all have an important part to play in the research ecosystem. In the end this profits everybody because as the critical mass of research grows the easier it is to hire people. It’s like gravity — big centers attract more of the best researchers from around the world. The Science Ball is a — uniquely Viennese — sign of this. We are now firmly “on the map”, and in Vienna you show that by hosting a ball!

Kabat: I agree. IIASA has a number of fruitful connections with Viennese institutions. For example, IIASA and OäW have worked together to organize a series of public lectures and debates with prominent scientists for the Viennese academic and political community. Our scientific collaborations with researchers in Vienna and Austria as a whole are also very strong, and have resulted in the publication of over 1050 scientific papers since 2008.

The Science Ball, bringing together Vienna’s diverse scientific community.

Vienna is known as the “City of Music” because of its musical legacy, but why is science not also an important part of the city’s image?

Kabat: This is something close to my heart. IIASA is doing top-level science on transitions towards sustainability; the world is now at a cross-roads and we need to be taking steps in sectors from energy and water all the way to financial systems. Communicating this can be very difficult, so we are using new and unusual collaborations that are made possible by this fantastic Viennese environment. We are working with music, ballet, and the opera. We have partnered up with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, for example, and with dancers from the State Opera to communicate these complex concepts. Science and the arts both have a vital part to play in Vienna’s past and future. I dream of a scientific tour through Vienna featuring collaborations between theatres, museums, and scientific institutions.

Henzinger: There is a lot of history between the golden age of science in Vienna and today, and I think there is a large amount of effort and also a lot of progress in reviving Vienna as a city for science. Science by its very nature is one of the most borderless activities of humanity there is and it can only thrive in a completely open environment. It is no surprise that the glory days of science in Vienna were when it was the hub of a multi-national empire. I think we can only get back to that by becoming much more open-minded and much more international as a country.

The city of Vienna is not legally responsible for science funding, but it is a central research hub and the biggest university city in central Europe. What can the city do to improve its image as a center of scientific excellence?

Kabat: I think a change is needed in the portrayal of Vienna as a whole. There is promotion of music, dance, and the arts. All these are great, but institutions like IST Austria and IIASA should also be used to show that Vienna really is one of the major science hubs of Europe and the world. Emphasizing this would require very little investment but would benefit both Vienna and science in the city. All the components are here, what it needs is a coordinated effort and a vision.

Henzinger: Vienna has an enormous advantage in that is known as a fantastic place to live. The city needs to actively attract not only world-class researchers but all kinds of science-related businesses and organizations. Vienna as a whole must make concerted effort to advertise itself as an attractive location for students, companies, and professionals from all over the world.

Students do not know that if they come to study at Vienna University, for example, they may also be able to benefit from collaborations with scientists working IIASA and IST Austria, who may be able to advise or even co-supervise them. This dynamic and varied environment is a key part of what Vienna can offer, not only the individual institutions. The ball is the perfect step in that direction. It is very clearly an effort that transcends any particular institution.

Kabat: We should continue this talk, not just with the two of us but with all leaders of Viennese scientific institutions, and the mayor, to have a free and frank discussion. Science brings a huge amount to the city of Vienna and it should be recognized. The ball, as you say, is an excellent occasion to bring together Vienna’s vibrant scientific community and celebrate it!

Aug 27, 2015 | Communication, Science and Art

By Gloria Benedikt, IIASA Associate for Science and Arts

Gloria Benedikt speaks at “Towards a Sustainable Future,” Palais Niederoesterreich, March 2015. Photo: Matthias Silveri

“For the real human story, history must comprise both the biological and the cultural,” wrote biologist Edward O. Wilson in his 2014 book The Meaning of Human Existence. ”The convergence between those two great branches of learning (sciences and humanities) will matter hugely when enough people have thought its potential through”.

This elegantly summarizes why I find myself at IIASA. I’ve been splitting my life between the arts (working as a professional dancer) and academia (studying at Harvard University). Over time I started to make connections between seemingly opposing worlds: arts and science. Now my challenge as IIASA Associate for Science and Arts is to help bridge them.

Why is this important, and why now? Because the way the world is run assumes that human beings act rationally and that economic (material) well-being in itself is key in solving all major issues afflicting our world. We have focused on the biological and neglected the cultural; we assumed that satisfying basic needs to keep bodies functioning will keep people alive. In short, we looked at the body and overlooked the soul. Or as prominent Czech Economist Tomáš Sedláček framed it, “There were huge advances that were brought upon us thanks to science and also thanks to economics, but now I feel we are in a time where we see the limits of it. In the beginning, there was no analytics, just ethics. Today there is only analytics and no ethics.”

Gloria Benedikt (left) and Hussein Khadour (right) answer questions from young scientists at a dress rehearsal of their new performance, InDignity, at the Festspielhaus St. Poelten

There was a time when humanity was already closer in finding a balance between the two. It was called the Enlightenment. “The Enlightenment quest,” Wilson observed, “was driven by the belief that human beings can know all that needs to be known, and in knowing understand, and in understanding gain the power to choose more wisely than ever before.”

Then, for the next two centuries and to the present day, science and humanities went their own way. Complex reasons briefly summarized: albeit making good progress, scientists were nowhere close to meeting expectations and artists sought meaning in other more private venues.

Is there any value in resuming this quest of connecting arts and science now? Wilson argues that the answer is yes, “because enough is known today to make it more attainable than during its first flowering.” And yes, because the solutions of so many problems in modern life will depend on solutions for the clash of competing religions, the revival of moral reasoning and on adequate foundations of environmentalism.

So, how can this work in practice?

Gloria Benedikt and Mimmo Miccolis in GROWTH, Kennedy Center, Washington DC, July 2014 Photo: Morgan Marinoni

For starters we should be aware that there is a common foundation. Despite science and humanities being fundamentally different from each other in what they say and do, they are complementary to each other in origin, as they arise from the same creative process in the human brain. But there is more. “Good” science is data driven. Scientists are trained to present their findings in a neutral way. A scientist appealing to emotion is likely to be considered unprofessional.

Meanwhile, artists are masters of metaphors and of appealing to emotion. At the same time, the majority religiously avoids being explicit. “Good” art is not dogmatic. We prefer to leave it up to our audiences to find meaning for themselves.

In the past 150 years, we have seen that if we push our noble pursuits to the extreme, we risk losing our purpose because we lose our link to society. If people don’t understand how scientific findings matter to them and if artists are too scared or simply too wound up in their own world, and thus fail to articulate, our work falls short of its ultimate purpose: to serve society by revealing truths in the world around us so that people can make better-informed decisions on how to go about their work and lives and shape the direction of our planet and the over 7 billion people populating it.

Arts and science need to be free – in 2015, I believe this freedom lies in the ability to present our findings clearly and independently. This quest, coupled with a new sense of responsibility to communicate, is what can and should bring scientists and artists together in the coming years and decades. I, for one, am excited that IIASA has opened its doors for us to join hands so we can create a sustainable future together and perhaps fulfill Wilson’s vision of a second enlightenment along the way.

Please note: I use the terms ‘humanities’ and ‘arts’ interchangeably here. However the term humanities is of course technically broader, as it includes not only the creative arts, but also political theory & philosophy.

References

Wilson, Edward O. The meaning of Human Existence. New York: Norton & Company, 2014

Sedláček, Benedikt, Twaalfhoven. Arts Economics and the Irrational – A debate in 3 Acts. November 29th 2015. www.vimeo.com/120531313

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.