Jun 4, 2018 | Demography, Postdoc, Poverty & Equity, Women in Science

©Nandita Saikia

By Nandita Saikia, Postdoctoral Research Scholar at IIASA

Being an author of a research article on excess female deaths in India in Lancet Global Health, one of the world’s most prestigious and high impact factor public health journals, today I questioned myself: Did I dream of reaching here when I was a little school going girl in the early nineties in a remote village in North East India?

I am the fourth daughter of five. In a country like India, where the status of women is undoubtedly poorer than men even now, and newspapers are often filled with heinous crimes against women, you may be able to imagine what it meant being a fourth daughter. Out of five sisters, three of us were born because my parents wanted a son. My mother, who barely completed her school education, did not want more than two children irrespective of sex, but was pressurized by the extended family to go for a boy after a third daughter and six years of repeated abortions.

I was told in my childhood that I was the most unwanted child in the family. I was a daughter, terribly underweight until age 11, and had much darker skin than my elder sisters and most people from our area, who have fairer skin than average in India. At my birth, my father, a college dropout farmer, was away in a relative’s house and when he heard about the arrival of another girl, he postponed his return trip.

This is a real story, but just one of those still happening in India. The fact that the girls of India are unwanted was observed from the days of early 20th century when it was written in the 1901 census:

“There is no doubt that, as a rule, she [a girl] receives less attention than would be bestowed upon a son. She is less warmly clad, … She is probably not so well fed as a boy would be, and when ill, her parents are not likely to make the same strenuous efforts to ensure her recovery.”

Regrettably, our current study shows that negligence against “India’s daughter” continues to this day.

Discrimination against the girl child can be divided in two categories: before birth and after birth. Modern techniques now allow sex-selective abortion. Despite strong laws, more than 63 million women are estimated to be ‘missing’ in India and the discrimination occurs at all levels of society.

Our present study deals with gender discrimination after birth. We found that over 200,000 girls under the age of five died in 2005 in India as a result of negligence. We found that excess female mortality was present in more than 90% of districts, but the four largest states of North India (Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan, and Madhya Pradesh) accounted for two thirds of India’s total number.

I have to tell you that I was luckier than most girls. Although I was an unwanted child in our extended family, to my mother, this underweight, dark-skinned, little girl was as cute as the previous ones! She gave her best care to her daughter, and she named her “Rani” meaning “Queen” in Assamese. I am still called by this name in my family and in my village.

When I grew up, I asked her several times about her motive for calling me Rani. She always replied: “You were so ugly, the thinnest one with dark skin, I named you as “Rani” because I wanted everyone to have a positive image before seeing you! Also, it is the name of my favorite teacher in high school and she was also a very thin but bright lady!”

The positive conversations with my mother played a crucial role to my desire to have my own identity, and influenced greatly my positive image of myself and my belief that I could do something worthwhile with my life. Much later, when I started my PhD at International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), Mumbai, I was surprised to learn that in Maharashtra, one of the wealthiest states of India, second or third daughters are not even given a name, but instead are called ‘Nakusha’, meaning unwanted.

My parents were passionate about educating their daughters, even with their limited means. My father, who was disappointed at my birth, left no stone unturned for my education! By the time I completed secondary school, our village, as well as neighboring villages, congratulated me during the Bihu celebration (the biggest local gathering) for my good performance in school exams. My parents were proud of me by that time; yet, for some strange reason, they always felt themselves weaker than our neighbors who had sons.

Now, people from our village are proud of me not just because I teach in India’s premier university, or that I take several overseas trips in a year, but because they realize that daughters can equally bring renown to their village; daughters can be married off without a dowry; daughters can equally provide old age care to their parents; daughters too can buy property! Due to this attitude and lower fertility levels, many couples now don’t prefer sons over daughters. In a village of 200 households, there are 33 couples that have either one or two daughters, yet did not keep trying for sons. In my own extended family, no one chooses to have more than two children irrespective of their sex. The situation has changed in my village, but not everywhere.

What is the solution of this deep-rooted social menace? We cannot expect a simple solution. However, my own story convinces me that education can be a game changer, but not necessarily academic degrees. I mean a system by which girls realize their own worth and their capability that they can be economically and socially empowered and can drive their own lives. With the help of education, I made myself from an “unwanted” to a wanted daughter!

The purpose of sharing my story is neither self-promotion nor to gain sympathy, rather to inspire millions of girls, who face numerous challenges in everyday life just because of their gender, and doubt their capability, just like I did in my school days. They can make a difference if they want! Nothing can stop them!

Mar 15, 2018 | Poverty & Equity, Women in Science

Monika Bauer, IIASA Alumni Officer

International Women’s Day is celebrated worldwide every year on 8 March. The event aims to promote the work and rights of women. This year, IIASA celebrated International Women’s Day with a panel discussion which asked the question, “Can a women-empowered world resolve some of the global sustainability challenges?” IIASA Population Researcher Raya Muttarak, moderated the panel that included Tyseer Aboulnasr, Melody Mentz, Shonali Pachauri, and Mary Scholes.

“The IIASA Women in Science Club chose this topic because it would allow the panelists to reflect on the potential welfare benefits of a more gender-balanced world. We wanted to know if balance could benefit both women and men, and we wanted to provide a space to discuss the potential intersectionality of the challenges to female empowerment such as poverty, racism, sexism, access to education, health autonomy, and resource inequality,” said organizer Amanda Palazzo, IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management researcher.

IIASA Director General and CEO Professor Dr. Pavel Kabat opened the discussion by offering a brief history of International Women’s Day in the context of the early history of IIASA.

Melody Mentz gives her thoughts

Mentz, an independent higher education research and evaluation consultant based in South Africa, spoke about the implications that a gender-balanced world could hold for science and sustainability using the African agricultural system as an example. To this end, she presented a few statistics that show how the African food system intersects with the sustainable development goal of gender equality.

According to the most recent Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations study, women do up to 50 % of agricultural labor in Africa (this varies by country). Bearing this fact in mind, women however, own only 10 % of the land in Africa; they receive less than 10% of the investments in agriculture on the continent; and less than 5% of women have access to advisory services. In addition, they hold just 14% of management positions in the sector, and only one in four agricultural researchers on the continent is female.

“There is a huge disparity between the contributions of women, the impact of the current food system on women, and the role that the environment allows them to play,” explained Mentz.

As far as the implications of this are concerned, the first, and perhaps the most obvious, is that we need more women in science. Secondly, according to Mentz, we also need more science for women.

“At an institutional level we [should] start thinking differently about what kind of questions we answer. Those questions don’t have to be focused on women, but rather, should consider the implications for both men and women,” she said.

Thirdly, she argued for more science with women, as many research questions and research designs are not just driven by scientists, but actually originate with the people that researchers are trying to help. Finally, we also need more science about women, meaning that data and indicators of impact need to include gender, especially in the context of Africa.

IIASA Energy Researcher Pachauri reflected on the inequalities that we see in our everyday lives. Her work specializes in household energy access in the developing world. Pachauri shared an example from an organization called ENERGIA, of which she is a member of the advisory board, where women were included as microentrepreneurs in the delivery of energy in villages. The organization found that female entrepreneurs were more successful and profitable than the men, which they put down to a greater use of social networks and relationships. The example demonstrated how societies can benefit from including women in solutions for everyday problems.

Aboulnasr, a retired electrical engineering professor, focused on the importance of balance – whether it is a balance of genders, social classes, or geography. Aboulnasr eloquently suggested that rather than striving for perfect balance, one should accept a more dynamic and changing balance. She also stated that one should focus on the impact, rather than on the tools. For example, excellent science is a tool for reaching a goal that makes an impact, rather than excellence in science being the goal. Her advice to the audience was to be open to accepting failure in one’s life.

“If you don’t fail in 30% of what you attempt to do, then you have never reached your limits,” she said, and encouraged the audience to stop obsessing about the failures of the past, seek balance, and to not feel guilty.

Scholes, a professor at the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa, approached the question of the day differently. She urged the audience to look at the question from a sustainability perspective, and to ask what role gender has to play in stewardship for the planet. In addition, she asked the audience to consider whether our unstainable use of resources is because of gender inequality, or because of a more underlying misalignment of values, and what type of empowerment might be needed to achieve a more sustainable world.

“As far as we know, this is the first panel discussion hosted at IIASA which has specifically tried to examine the role of women in achieving a sustainable future. We learned that there are pockets of IIASA research already exploring this this issue and that there is room and interest to engage in this discussion in the future,” says Palazzo.

It is clear that there is no simple answer to the issues surrounding the topic of our International Women’s Day panel discussion. The event however, highlighted unique reflections and experiences from each panelist, and the IIASA Women in Science Club will continue to explore and push the discussion forward. We look forward to updating you soon.

Some of of the panel discussion attendees wearing red, purple and black themed clothes for International Women’s Day

Jan 22, 2018 | Energy & Climate, Poverty & Equity

By Narasimha Rao, Project Leader of the Decent Living Energy (DLE) Project, IIASA Energy Program

Is there a conflict between reducing global income inequality and combating climate change? This seems like an odd question, given that these challenges have a lot in common. Raising the living standard of the poor for example, makes them resilient to climate impacts; less inequality can mean more political mobilization to establish climate policies; and changes in social norms away from material accumulation can reduce inequality and emissions. Academics have however been curious about the following phenomenon: In many countries, a dollar spent at higher income levels is less energy intensive than at lower income levels (known as “income elasticity of energy”). That is, rich people – although they consume much more in total – spend additional income on services or can afford energy-efficient goods, while the new middle class buy energy-intensive goods, like appliances and cars.

Many imagine China as a template for this type of fast growth. If globally significant, this effect would imply that growth that is more equitable would also be more emissions-intensive, and that we would have to pay particular attention to ensuring that climate policies reach the rising middle class in developing countries. While several studies have examined this phenomenon in specific countries, no one has examined its global significance. We set out to do that.

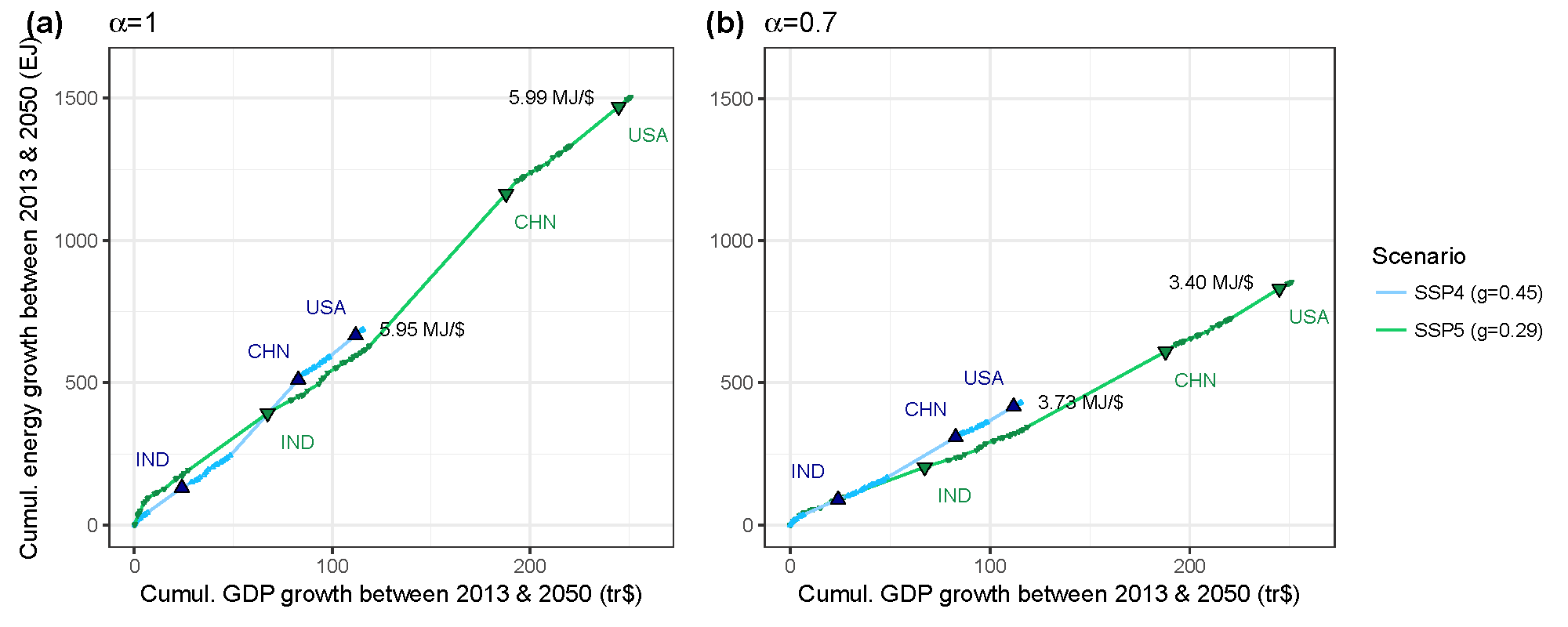

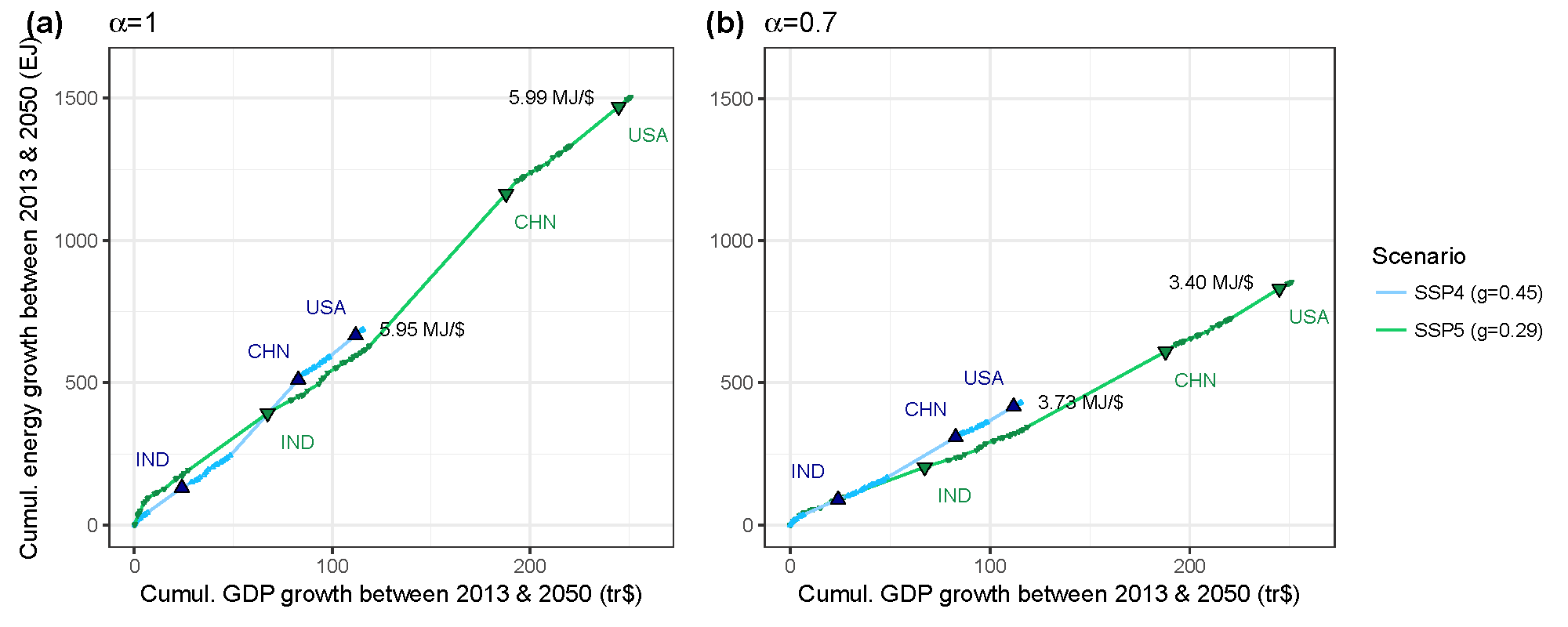

Energy intensity (MJ per $) lower in a high-growth, low inequality world (green line, Gini=0.29) compared to a low-growth, high inequality world (blue line, Gini=0.45). Gini reflects between-country inequality only.

Our analysis suggests that the energy-increasing effect of lowering inequality is more of a distraction than a concern. We compared scenarios of equitable and inequitable income growth, both within and between countries, assuming the most extreme manifestation of the income elasticity. Within any country, given the slow pace at which inequality typically evolves even with the most extreme known income elasticity and reduction in country inequality, greenhouse gas emissions would increase by less than 8% over a couple of decades. However, when one considers a more equitable distribution of growth between countries, global emissions growth may decrease when compared to growth that occurs in industrialized countries. This is because poorer countries have more potential for technological advancements that reduce the energy intensity of growth than richer countries do. That is, more income growth in poorer countries provides more opportunity for efficiency improvements that influence the emissions of very large populations. Furthermore, China is a poor model for poor countries at large, many of which have relatively low energy intensities, even today.

Climate stabilization at the level aspired to by the Paris Climate Agreement requires that we (i.e. the world) decarbonize to zero annual emissions around 2050, which means that even developing countries have to make aggressive strides towards integrating climate goals into development. Nevertheless, there is no sufficient basis for considering that equitable growth, and by implication the poor’s energy intensity, is part of the problem. To the contrary, the potential for co-benefits from equitable growth for climate change are enormous, but unfortunately under-explored, particularly in quantitative studies. Research should focus on quantifying the role of changing social norms – less consumerism, political mobilization, and other social changes that are typically associated with lower inequality – on reducing greenhouse gases.

Reference:

Rao, ND, Min J. Less global inequality can improve climate outcomes. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change. 2018;e513. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.513

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 21, 2017 | Alumni, Poverty & Equity, Young Scientists

By Nemi Vora, participant of the IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) 2017 and PhD student at the University of Pittsburgh.

“Was it worth the flight?” asked my fellow alumna of the YSSP Karen Umansky, at the end of our first day of attending the World Science Forum in Jordan. The total journey from the USA to Jordan had taken 20 hours, layovers included. She was well aware of my travel anxiety, fear of immigration officials (an Indian passport doesn’t always make things easy), and fear of traveling alone on a militarized Dead Sea road at night (you can see the west bank on the other side). I had spammed her every day about it.

The IIASA delegation at the World Science Forum © IIASA

I didn’t have an answer; the panels I attended did not focus on anything new. We were all aware of issues: digitization without destruction, women in science, support for emerging scientists, meeting the sustainable development goals, and so on. However, every conference has a different key to unlock its potential and Jan Marco Müller, head of the IIASA directorate office and another recipient of my daily email spam, informed me that it was not the panels, but the corridor conversations that mattered here.

I soon found out that it was not just the corridors, but even the brief conversations in shuttles where the conference happened. I met a program manager for the US National Science Foundation who told me about research work on the food-energy-water nexus that they funded for the Nile, an area similar to my thesis. I met a regional director of UNESCO and a science minister from Colombia, who together set up new Africa-Latin America project partnerships during the shuttle ride.

One important part of each conversation was the significance of the place I was in, something I had previously missed completely. The ability of this small country, surrounded by conflict zones on each side, to arrange for such a large gathering of this kind, bringing together opponents and allies alike, and to take a stand for enabling peace through science, was remarkable.

True, the issues were not new, but the context was much more specific to the needs of a conflict-ridden world. For instance, discussing how to provide access to digital resources such as open data for policymaking or scientific journals for all the countries, promoting the achievements of Arab women scientists and those of the other developing regions amidst cultural and economic hardships, and fostering innovation in emerging scholars in the developing world where lack of resources was part of academic life.

Jordan also showcased the recently established SESAME facility: the Middle East’s first international science research center, a joint venture of a group of middle eastern countries, otherwise engaged in political conflicts. IIASA was representing a unique position here: originally founded as the bridge between East-West scientific collaboration during the Cold War, it served as an example, along with the fledgling SESAME, that geo-political boundaries did not hinder science and that such projects could be successful. Despite political tensions in individual countries, and having a passport that would not allow you to visit your colleague’s country, you could still work side-by side—a feat that SESAME scientists achieve every day.

As YSSPers, our goal was to talk about the benefits of global mentorship and how that could be leveraged to address the uneven distribution of resources. All of us came from different backgrounds: there was An Ha Truong from Vietnam, an energy economist studying optimization of biomass for coal power plants, there was Karen, the social scientist from Israel, studying emerging neo-Nazism in Europe, and then there was me—representing the USA and India as an environmental engineer.

Our co-panelists from the Berkeley Global Science Institute, also of diverse backgrounds, were engaged in setting up labs across the world, providing resources and mentorship to graduate students. While we had a lively session discussing our personal experiences, it wasn’t what we had to say but the session questions that struck a chord with us. The presence of conflicts add another layer of complexity to the already murky path of academia: how do you keep young scholars motivated to stay in the lab and work in a country threatened by war? How do you compete in cutting-edge science research when resources are scarce? How do you engage in public-private partnerships when your work may be more theoretical than applied?

The YSSPers taking part in a panel © IIASA

We need to collaborate more, provide access to the data and codes we use to carry out reproducible research, attempt to publish in open access platforms whenever feasible, and support our fellow scientists irrespective of their location or positions. This way, we would inch closer to solving some of these issues. Six months ago at IIASA, the HRH Sumaya bint El Hassan, co-chair of the World Science Forum, had asked me, “How do you eat an elephant?” Being a vegetarian, I couldn’t imagine ever eating one and I very naively told her so. On my way back from Jordan, with another long journey ahead of me, I realized the significance of her words: you eat it little by little.

Follow Nemi on twitter: @NemiVora

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 26, 2017 | Alumni, Climate Change, Poverty & Equity, Sustainable Development, Water, Young Scientists

Adil Najam is the inaugural dean of the Pardee School of Global Studies at Boston University and former vice chancellor of Lahore University of Management Sciences, Pakistan. He talks to Science Communication Fellow Parul Tewari about his time as a participant of the IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) and the global challenge of adaptation to climate change.

How has your experience as a YSSP fellow at IIASA impacted your career?

The most important thing my YSSP experience gave me was a real and deep appreciation for interdisciplinarity. The realization that the great challenges of our time lie at the intersection of multiple disciplines. And without a real respect for multiple disciplines we will simply not be able to act effectively on them.

Prof. Adil Najam speaking at the Deutsche Welle Building in Bonn, Germany in 2010 © Erich Habich I en.wikipedia

Recently at the 40th anniversary of the YSSP program you spoke about ‘The age of adaptation’. Globally there is still a lot more focus on mitigation. Why is this?

Living in the “Age of Adaption” does not mean that mitigation is no longer important. It is as, and more, important than ever. But now, we also have to contend with adaptation. Adaptation, after all, is the failure of mitigation. We got to the age of adaptation because we failed to mitigate enough or in time. The less we mitigate now and in the future, the more we will have to adapt, possibly at levels where adaptation may no longer even be possible. Adaption is nearly always more difficult than mitigation; and will ultimately be far more expensive. And at some level it could become impossible.

How do you think can adaptation be brought into the mainstream in environmental/climate change discourse?

Climate discussions are primarily held in the language of carbon. However, adaptation requires us to think outside “carbon management.” The “currency” of adaptation is multivaried: its disease, its poverty, its food, its ecosystems, and maybe most importantly, its water. In fact, I have argued that water is to adaptation, what carbon is to mitigation.

To honestly think about adaptation we will have to confront the fact that adaptation is fundamentally about development. This is unfamiliar—and sometimes uncomfortable—territory for many climate analysts. I do not believe that there is any way that we can honestly deal with the issue of climate adaptation without putting development, especially including issues of climate justice, squarely at the center of the climate debate.

COP 22 (Conference of Parties) was termed as the “COP of Action” where “financing” was one of the critical aspects of both mitigation and adaptation. However, there has not been much progress. Why is this?

Unfortunately, the climate negotiation exercise has become routine. While there are occasional moments of excitement, such as at Paris, the general negotiation process has become entirely predictable, even boring. We come together every year to repeat the same arguments to the same people and then arrive at the same conclusions. We make the same promises each year, knowing that we have little or no intention of keeping them. Maybe I am being too cynical. But I am convinced that if there is to be any ‘action,’ it will come from outside the COPs. From citizen action. From business innovation. From municipalities. And most importantly from future generations who are now condemned to live with the consequences of our decision not to act in time.

© Piyaset I Shutterstock

What is your greatest fear for our planet, in the near future, if we remain as indecisive in the climate negotiations as we are today?

My biggest fear is that we will—or maybe already have—become parochial in our approach to this global challenge. That by choosing not to act in time or at the scale needed, we have condemned some of the poorest communities in the world—the already marginalized and vulnerable—to pay for the sins of our climatic excess. The fear used to be that those who have contributed the least to the problem will end up facing the worst climatic impacts. That, unfortunately, is now the reality.

What message would you like to give to the current generation of YSSPers?

Be bold in the questions you ask and the answers you seek. Never allow yourself—or anyone else—to rein in your intellectual ambition. Now is the time to think big. Because the challenges we face are gigantic.

Note: This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Mar 7, 2016 | Poverty & Equity

Shalini Randeria, a sociologist and social anthropologist focused on legal pluralism and global inequalities, is the Rector of the Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) in Vienna and an IIASA Distinguished Visiting Fellow. On 9 March, she gave a keynote lecture in Vienna entitled, “Precarious livelihoods, disposable lives, and struggles for citizenship rights,” as part of the IIASA-Austrian Academy of Sciences public event, Human Capital, Geopolitical Complexities, and our Sustainable Future.

Q. Why do you say that globalization is full of contradictions?

A. We are living in paradoxical times. The global spread of democracy has gone hand in hand with the erosion of its substance. Decisions once made by national parliaments are now made by supranational institutions, reducing the say of citizens in public decision-making. As people feel disenfranchised, trust in our governments fades. Sometimes going to court seems to be the only way to make governments accountable to citizens. This development not only expands the power of the judiciary but also politicizes it.

What role does globalization play in the inequality between Global North and Global South?

Neo-liberal economic restructuring has increased inequalities between countries but also within each society. We are witness today to an unprecedented concentration of income and wealth, which is not an unforeseen consequence of economic globalization but the result of deliberate public policies. The global South, however, is no longer a geographical category. Greece is an example of European country dependent on international finance institutions in much the same way that once so-called developing countries were.

Shalini Randeria © IWM / Dejan Petrovic.

You say that economic and political processes render some lives disposable – what do you mean by that?

Take India for instance: since the country’s independence in 1947, every year some 500,000 people—mostly small farmers, agricultural workers, fishing and forest-dwelling communities —have been forcibly displaced to make room for gigantic infrastructure projects. They have become development refugees in their own country. These people are regarded as ‘dispensable’ by the state in the sense that their livelihoods are destroyed, their lives disrupted, and they are denied access to common property resources. These populations are the human waste that is sacrificed at the altar of an unsustainable model of incessant economic growth.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted last year, include aims to end poverty, ensure access to employment, energy, water, and reduce inequality, at the same time as preserving the environment. What challenges do you see for achieving these goals?

The SDGs will prove to be an important milestone, if they are implemented the world over. Some of these goals are in conflict with one another. Take the protection of biodiversity, for example, which is often constructed as an antagonistic relationship between society and nature In the new global regime of biodiversity consveration, nature is portrayed as self-regulating, as a pristine, uninhabited wilderness that is threatened due to the wasteful resource use by local populations. Thus access and traditional usufruct rights are curtailed, and indigenous knowledge is devalued and marginalized. The (post)colonial transformation of landscapes into “environment,” “natural resources,” and “biodiversity” has enclosed the commons in most regions of the global South and often commercialized them.

The idea of the Global Commons as spaces and resources that all have access to and also have the responsibility to protect is a useful one in this context. The oceans are but one example of the global commons that include water, forests, or air, which are all being increasingly privatized. The Global Commons also include common resources developed by humans such as virtual data, knowledge, computer software, and medication..

What needs to be done by international institutions to make significant progress in achieving the SDGs?

Eliminating poverty will need an understanding of it that goes beyond a merely economic one. One will need to take into account possibilities of democratic participation, access to public goods and infrastructure, as well as civil rights and a restoration of a plurality of livelihoods. But these institutions also need to be reformed as they have a serious democracy deficit, be it the EU or the Bretton Woods institutions. Unaccountability of international institutions and powerful corporations along with stark asymmetries of power between these and the nation-states characterizes the new architecture of global governance, which need to be remedied urgently if we are to realize global justice.

Note: This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.