Jun 4, 2018 | Economics, Eurasia

By Michael Emerson, Associate Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for European Policy Studies, and Senior Research Scholar at IIASA

Any substantive common economic space from ‘Lisbon to Vladivostok’ would require the reduction or elimination of tariffs and key non-tariff barriers (such as technical product standards) within a wide-ranging free trade agreement (FTA). For the EU this seems to be an advantageous proposition from an economic standpoint. However, one would expect the pre-conditions posed by the EU for the opening of negotiations to be several and stringent, particularly in terms of political progress over the Ukraine conflict, Belarus’ membership of the World Trade Organization (WTO), and better compliance with WTO rules, with a reduction in protectionist policies in Russia especially.

© Rawpixel.com | Shutterstock

The issue of tariffs is of high political and economic significance, but still a conceptually simple matter. By contrast, the removal of non-tariff barriers is immensely complex, involving dozens or hundreds of regulations and thousands of product standards. We therefore examined the non-tariff issue in some detail [1].

Surprising as it may seem, the harmonization of product standards has actually already progressed as a result of the autonomous policy of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and its member states to adopt increasingly international and European standards. Around 30 sector-specific framework regulations have been adopted by the EAEU, based on EU directives, and backed up by some 5,830 product-specific standards, which are identical to those of the EU (to a large degree EU standards are identical to those of the International Standards Organization).

Therefore, at least for industrial products, there is already a promising basis for an agreement between the EU and EAEU. An important further step could be a mutual recognition agreement (MRA) for conformity assessment. This would mean that each party’s accredited standards agencies would be empowered to certify the conformity of their exporters’ products with standards required by the importing state, without further testing or certification in the importing country. An MRA would thus significantly reduce the cost of non-tariff barriers. An example of this type of agreement is the one between the EU and the US that has been functioning effectively without the scrapping of tariffs in an FTA.

It would also in principle not only be possible, but more plausible to establish a stand-alone MRA between the EU and the EAEU earlier than as part of a wider ranging free trade agreement that also scraps tariffs. This is because under the rules of the WTO, member states cannot enter into a free trade agreement with non-member states. This specifically concerns the situation of Belarus as the only non-WTO member state of the EAEU. However, this limitation under WTO rules does not apply to MRAs of the type mentioned.

An MRA could of course also be incorporated into a more ambitious FTA that scraps tariffs. There is however also the fundamental question of whether the EAEU and its member states would consider this to be in their interests.

So far, this has been very unclear. In Russia, one hears the argument that an FTA with the EU would be too imbalanced in favor of the EU. Indeed, most Russian exports to the EU, such as oil and gas, are already being traded without tariffs. It should be noted that the EAEU is currently negotiating a ‘non-preferential’ agreement with China, which means that tariffs would not be eliminated. While the slogan ‘Lisbon to Vladivostok’ has featured in many speeches, there is much more caution on both sides when the practicalities of a FTA are considered.

It would still be possible for an FTA between the EU and EAEU to be sensitive to the concerns of the EAEU by being ‘asymmetrical’–meaning that while the EU could scrap its tariffs immediately, the EAEU might do this over a transition period of several years. An example of this is the EU’s deep and comprehensive free trade agreement (DCFTA) with Ukraine, which sees some of the most sensitive sectors getting transitional delays of up to ten years.

These scenarios cannot go ahead for the time being for the reasons already stated above. However, the main point is that there are well-specified concepts available for a possible agreement to scrap tariffs and non-tariff barriers between the two parties. For the EU this would be attractive as an economic proposition. Whether this could see consensus among EAEU member states is however not so clear. A very narrow cooperation agreement that does not include free trade would be of limited interest to the EU.

References

[1] Emerson M & Kofner J (2018). Technical Product Standards and Regulations in the EU and EAEU – Comparisons and Scope for Convergence. IIASA Report. Laxenburg, Austria

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Three IIASA papers on “Challenges and Opportunities of Economic Integration within a Wider European and Eurasian Space” will be presented in Moscow at the high-level conference “Prospects for a deeper EU – EAEU economic cooperation and perspectives for business” on 6 June. See event page.

May 30, 2018 | Economics, Food & Water, Sustainable Development, Systems Analysis

By Alan Nicol, Strategic Program Leader at the International Water Management Institute (IWMI)

I was at the local corner store in Uganda last week and noticed the profusion of rice being sold, the origin of which was from either India or Pakistan. It is highly likely that this rice being consumed in Eastern Africa, was produced in the Indus Basin, using Indus waters, and was then processed and shipped to Africa. That is not exceptional in its own right and is, arguably, a sign of a healthy global trading system.

Nevertheless, the rice in question is likely from a system under increasing stress, one that is often simply viewed as a hydrological (i.e., basin) unit. What my trip to the corner store shows is that perhaps more than ever before a system such as the Indus is no longer confined–it extends well beyond its physical (hydrological) borders.

Not only does this rice represent embedded ‘virtual’ water (the water used to grow and refine the produce), but it also represents policy decisions, embedded labor value, and the gamut of economic agreements between distribution companies and import entities, as well as the political relationship between East Africa and South Asia. On top of that are the global prices for commodities and international market forces.

In that sense, the Indus River Basin is the epitome of a complex system in which simple, linear causality may not be a useful way for decision makers to determine what to do and how to invest in managing the system into the future. Integral to this biophysical system, are social, economic, and political systems in which elements of climate, population growth and movement, and political uncertainty make decisions hard to get right.

Like other systems, it is constantly changing and endlessly complex, representing a great deal of interconnectivity. This poses questions about stability, sustainability, and hard choices and trade-offs that need to be made, not least in terms of the social and economic cost-benefit of huge rice production and export.

An aerial view of the Indus River valley in the Karakorum mountain range of the Basin. © khlongwangchao | Shutterstock

So how do we go about planning in a system that is in such constant flux?

Coping with system complexity in the Indus is the overarching theme of the third Indus Basin Knowledge Forum (IBKF) being co-hosted this week by the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), and the World Bank. Titled Managing Systems Under Stress: Science for Solutions in the Indus Basin, the Forum brings together researchers and other knowledge producers to interface with knowledge users like policymakers to work together to develop the future direction for the basin, while improving the science-decision-making relationship. Participants from four riparian countries–Afghanistan, China, India, and Pakistan–as well as from international organizations that conduct interdisciplinary research on factors that impact the basin, will work through a ‘marketplace’ for ideas, funding sources, and potential applications. The aim is to narrow down a set of practical and useful activities with defined outcomes that can be tracked and traced in coming years under the auspices of future fora.

The meeting builds on the work already done and, crucially, on relations already established in this complex geopolitical space, including under the Indus Forum and the Upper Indus Basin Network. By sharing knowledge, asking tough questions, and identifying opportunities for working together, the IBKF hopes to pin down concrete commitments from both funders and policymakers, but also from researchers, to ensure high quality outputs that are of real, practical relevance to this system under stress–from within and externally.

Scenario planning

Feeding into the IBKF3, and directly preceding the forum, the Integrated Solutions for Water, Energy, and Land Project (ISWEL) will bring together policymakers and other stakeholders from the basin to explore a policy tool that looks at how best to model basin futures. This approach will help the group conceive possible futures and model the pathways leading to the best possible outcomes for the most people. This ‘policy exercise approach’ will involve six steps to identify and evaluate possible future pathways:

- Specifying a ‘business as usual’ pathway

- Setting desirable goals (for sustainability pathways)

- Identifying challenges and trade-offs

- Understanding power relations, underlying interests, and their role in nexus policy development

- Developing and selecting nexus solutions

- Identifying synergies, and

- Building pathways with key milestones for future investments and implementation of solutions.

The summary of this scenario development workshop and a vision for the Indus Basin will be shared as part of the IBKF3 at the end of the event, and will help the participants collectively consider what actions can be taken to ensure a prosperous, sustainable, and equitable future for those living in the basin.

The rice that helps feed parts of East Africa plays a key global role–the challenge will be ensuring that this important trading relationship is not jeopardized by a system that moves from pressure points to eventual collapse. Open science-policy and decision-making collaboration are key to making sure that this does not happen.

This blog was originally published on https://wle.cgiar.org/thrive/2018/05/29/rice-and-reason-planning-system-complexity-indus-basin.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 2, 2018 | Alumni, Economics, IIASA Network, Science and Policy

W. Brian Arthur from the Santa Fe Institute (SFI), and a former IIASA researcher, talks about increasing returns and the magic formula to get really great science.

Recently, Brian stopped in at the Complexity Science Hub Vienna, of which IIASA is a member institution, and spoke to Verena Ahne about his work.

Brian Arthur (© Complexity Science Hub)

Brian, now 71, is one of the most influential early thinkers of the SFI, a place that without exaggeration could be called the cradle of complexity science.

Brian became famous with his theory of increasing returns. An idea that has been developed in Vienna, by the way, where Brian was part of a theoretical group at the IIASA in the early days of his career: from 1978 to 1982.

“I was very lucky,” he recalls. “I was allowed to work on what I wanted, so I worked on increasing returns.”

The paper he wrote at that time introduced the concept of positive feedbacks into economy.

The concept of “increasing returns”

Increasing returns are the tendency for that which is ahead to get further ahead, for that which loses advantage to lose further advantage. They are mechanisms of positive feedback that operate—within markets, businesses, and industries—to reinforce that which gains success or aggravate that which suffers loss. Increasing returns generate not equilibrium but instability: If a product or a company or a technology—one of many competing in a market—gets ahead by chance or clever strategy, increasing returns can magnify this advantage, and the product or company or technology can go on to lock in the market.”

(W Brian Arthur, Harvard Business Review 1996)

This was a slap in the face of orthodox theories which saw–and some still see–economy in a state of equilibrium. “Kind of like a spiders web,” Brian explains me in our short conversation last Friday, “each part of the economy holding the others in an equalization of forces.”

The answer to heresy in science is that it does not get published. Brian’s article was turned down for six years. Today it counts more than 10.000 citations.

At the latest it was the development and triumphant advance of Silicon Valley’s tech firms that proved the concept true. “In fact, that’s now the way how Silicon Valley runs,” Brian says.

The youngest man on a Stanford chair

William Brian Arthur is Irish. He was born and raised in Belfast and first studied in England. But soon he moved to the US. After the PhD and his five years in Vienna he returned to California where he became the youngest chair holder in Stanford with 37 years.

Five years later he changed again – to Santa Fe, to an institute that had been set up around 1983 but had been quite quiet so far.

Q: From one of the most prestigious universities in the world to an unknown little place in the desert. Why did you do that?

A: In 1987 Kenneth Arrow, an economics Nobel Prize winner and mentor of mine, said to me at Stanford: We’re holding a small conference in September in a place in the Rockies, in Santa Fe, would you go?

When a Nobel Prize winner asks you such a question, you say yes of course. So I went to Santa Fe.

We were about ten scientists and ten economists at that conference, all chosen by Nobel Prize winners. We talked about the economy as an evolving complex system.

Veni, vidi, vici

Brian came – and stayed: The unorthodox ideas discussed at the meeting and the “wild” and free atmosphere of thinking at “the Institute”, as he calls the Santa Fe Institute (SFI), thrilled him right away.

In 1988 Brian dared to leave Stanford and started to set up the first research program at Santa Fe. Subject was the economy treated as a complex system.

Q: What was so special about SF?

A: The idea of complexity was quite new at that time. But people began to see certain patterns in all sorts of fields, whether it was chemistry or the economy or parts of physics, that interacting elements would together create these patterns…To investigate this in universities with their particular disciplines, with their fixed theories, fixed orthodoxies–where it is all fixed how to do things–turned out to be difficult.

Take the economy for example. Until then people thought it was in an equilibrium. And there we came and proved, no, economics is no equilibrium! The Stanford department would immediately say: You can’t do that! Don’t do that! Or they would consider you to be very eccentric…

So a bunch of senior fellows at Los Alamos in the 1980s thought it would be a good idea if there was an independent institute to research these common questions that came to be called complexity.

At Santa Fe you could talk about any science and any basic assumptions you wanted without anybody saying you couldn’t or shouldn’t do that.

Our group as the first there set a lot of this wild style of research. There were lots of discussions, lots of open questions, without particular disciplines… In the beginning there were no students, there was no teaching. It was all very free.

This wild style became more or less the pattern that has been followed ever since. I think the Hub is following this model too.

The magic formula for excellence

Q: Was this just a lucky concurrence: the right people and atmosphere at the right time? Or is there a pattern behind it that possibly could be repeated?

A: I am sure: If you want to do interdisciplinary science – which complexity is: It is a different way of looking at things! – you need an atmosphere where people aren’t reinforced into all the assumptions of the different disciplines.

This freedom is crucial to excellent science altogether. It worked out not only for Santa Fe. Take the Rand Corporation for instance, that invented a lot of things including the architecture of the internet, or the Bell Labs in the Fifties that invented the transistor. The Cavendish Lab in Cambridge is another one, with the DNA or nuclear astronomy…

The magic formula seems to be this:

- First get some first rate people. It must be absolutely top-notch people, maybe ten or twenty of them.

- Make sure they interact a lot.

- Allow them to do what they want – be confident that they will do something important.

- And then when you protect them and see that they are well funded, you are off and running.

Probably in seven cases out of ten that will not produce much. But quite a few times you will get something spectacular – game changing things like quantum theory or the internet.

Don’t choose programs, choose people

Q: This does not seem to be the way officials are funding science…

A: Yes, in many places you have officials telling people what they need to research. Or where people insist on performance and indices… especially in Europe, I have the impression, you have a tradition of funding science by insisting on all these things like indices and performance and publications or citation numbers. But that’s not a very good formula.

Excellence is not measurable by performance indicators. In fact that’s the opposite of doing science.

I notice at places where everybody emphasize all this they are not on the forefront. Maybe it works for standard science; and to get out the really bad science. But it doesn’t work if you want to push boundaries.

Many officials don’t understand that.

In Singapore the authorities once asked me: How did you decide on the research projects in Santa Fe? I said, I didn’t decide on the research projects. They repeated their question. I said again, I did not decide on the research projects. I only decided on people. I got absolutely first rate people, we discussed vaguely the direction we wanted things to be in, and they decided on their research projects.

That answer did not compute with them. They are the civil service, they are extraordinarily bright, they’ve got a lot of money. So they think they should decide what needs to be researched.

I should have told them – I regret I didn’t: This is fine if you want to find solutions for certain things, like getting the traffic running or fixing the health care system. Surely with taxpayer’s money you have to figure such things out. But you will never get great science with that. All you get is mediocrity.

Of course now they asked, how do we decide which people should be funded? And I said: “You don’t! Just allow top people to bring in top people. Give them funding and the task of being daring.”

Any other way of managing top science doesn’t seem to work.

I think the Hub could be such a place – all the ingredients are here. Just make sure to attract some more absolutely first rate people. If they are well funded the Hub will put itself on the map very quickly.

This interview was originally published on https://www.csh.ac.at/brian-arthurs-magic-formula-for-excellence/

Jan 8, 2018 | Economics, Postdoc

By Isela-Elizabeth Tellez-Leon, IIASA-CONACYT postdoc in the Advanced Systems Analysis, Evolution and Ecology, and Risk and Resilience programs.

The rise of foreign investment in emerging economies after the global financial crisis of 2008-2009 has renewed interest in what drives such investment. My colleague at the Central Bank of Mexico and I examined the determinants of foreign investment, known as capital flows, into Mexico in 1995-2015, a period characterized by a free-floating exchange rate, that is, the authorities did not set an exchange rate.

Our research has useful findings for the design of economic policies because it provides measures that authorities can take to direct proper functioning of the economy. It also contributes to improved understanding of what influences capital flows into Mexico. We analyzed the determinants of each type of foreign investment separately, because different financial flows respond differently to the various external and internal factors. Mexico is an interesting case study because it experienced a large volume of capital investment after the commercial opening in the 1990s and more recently in the aftermath of the 2008-2009 financial crisis, as international investors were searching for high yields and security. In addition, the trading volume of Mexican government securities is one of the highest among emerging markets.

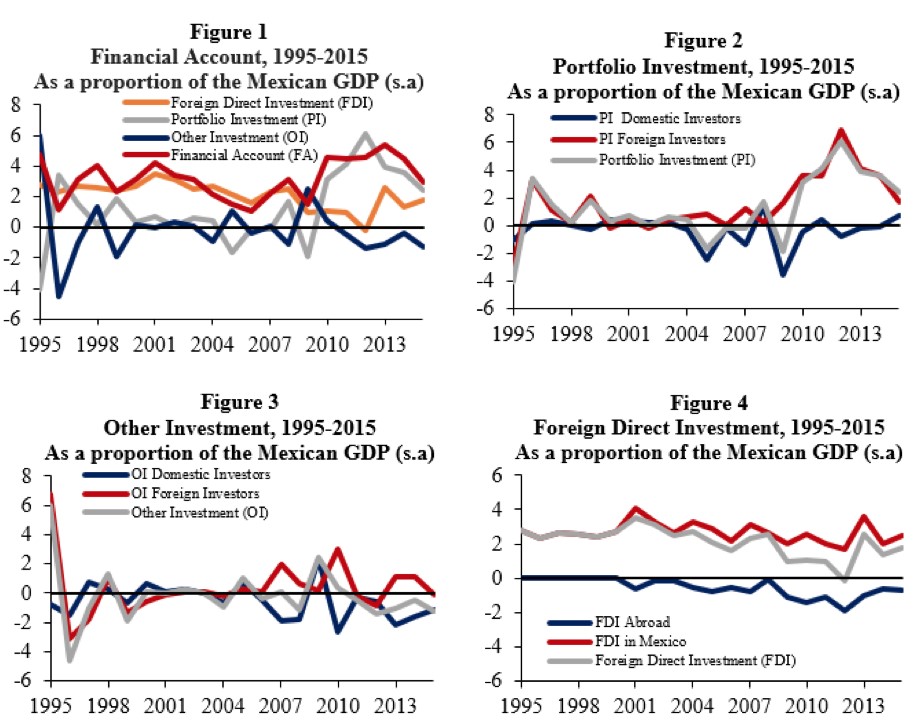

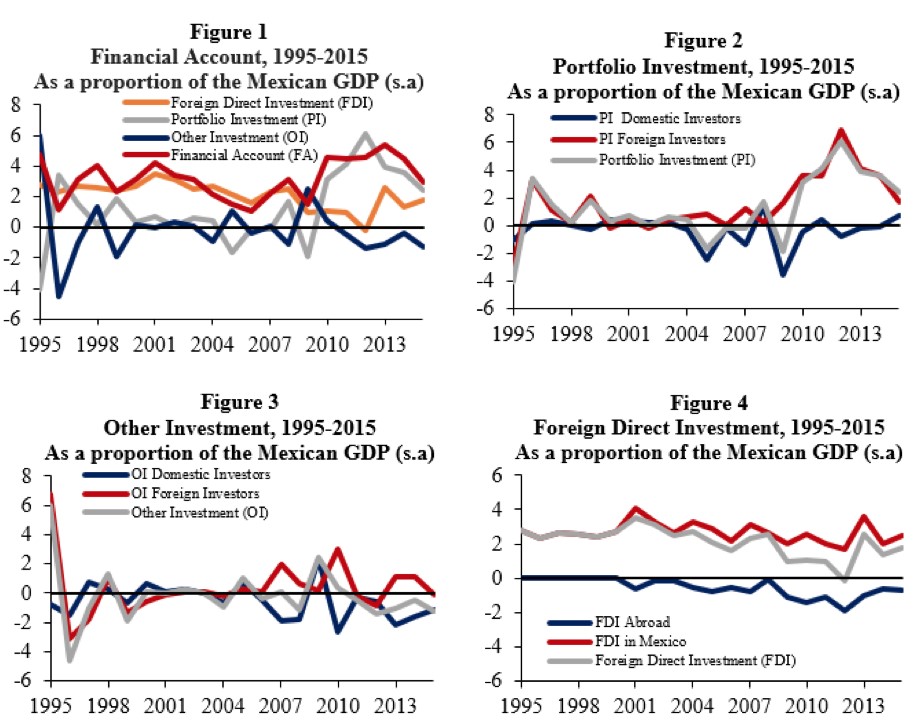

Capital flows are incorporated into financial accounts where foreign transactions are noted—including investments by foreign residents into Mexican public and private sector securities and by domestic residents in foreign securities. Mexico’s financial accounts (Figure 1) are composed of the following three components: portfolio investment (in terms of liquidity—i.e., the extent to which a market allows assets to be bought and sold at stable prices—this is a short-term investment, Figure 2), other investment (Figure 3), and foreign direct investment (in terms of liquidity this is a long-term investment, Figure 4).

The financial account is divided into three main areas: foreign direct investment (FDI), portfolio investment (PI) and other investment (OI). Figure 1 shows the net flows of foreign investment. Figure 2 displays portfolio investment (PI) and its components of domestic and foreign investors. Figure 3 and 4 show OI and FDI split into their different components. The figures show moving averages over 4 quarters adjusted for seasonality. Source: Elizabeth Tellez and the Central Bank of Mexico.

Portfolio and other investments tend to leave and enter a country quicker than foreign direct investment; thus, they are likely to respond faster to shocks. In particular, portfolio investment by foreign agents might have a different response compared to portfolio investment by domestic agents. For example, if foreign investors have timely information about the external economic conditions, they will likely respond faster to foreign shocks.

In general, foreign investment has an impact on developing economies in at least two ways. On the one hand, international borrowing allows a country to increase investment in the private sector, without sacrificing consumption. On the other hand, large foreign investment flows may be followed by increases in the prices of goods and services because of the strength of the exchange rate. In turn, this increases purchases of foreign products (imports), but exports decrease. In this way, a country’s foreign trade may become more vulnerable to external shocks and reversals of foreign investment.

Central Bank of Mexico © Elizabeth Tellez.

To analyze what determines capital flows in the short and medium term for Mexico, we used an econometric model known as Vector Autoregression. This model allows us to examine the impacts of different shocks on capital flows. We studied two sets of factors that can encourage investors to shift resources to emerging markets. The first set considers external shocks (push factors), which are beyond the control of developing countries, such as foreign interest rates or economic activity in advanced countries.

The push factors we examined were global risk, US liquidity, US GDP, and US interest rates. The second set of factors are the prevailing economic conditions in the emerging economy (pull factors). For these we considered Mexican GDP, interest rates, inflation, and exchange rates.

One of our main findings is that investors are risk averse and prefer to invest abroad when foreign interest rates are higher. Portfolio investment (PI) and other investment (OI) seem more responsive to short-term shocks than foreign direct investment (FDI), possibly because they tend to be more liquid than FDI. We also found that domestic conditions play a role in explaining capital flows. For instance, we found that higher GDP growth leads to higher portfolio investment, while higher interest rates and lower inflation generate higher inflows of other investment. Our work underlines the benefits of separately analyzing the components of capital flows. For instance, a shock to the federal funds rate has important effects on portfolio investment in public-sector securities by foreign residents. This is because public securities are the closest substitutes to US government bonds found in the Mexican financial market.

Reference:

Raul IR & Tellez Leon E (2017). Are all types of capital flows driven by the same factors? Evidence from Mexico. Banco de Mexico, Mexico.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.