By Finn Laurien, research assistant at the IIASA Risk and Resilience (RISK) Program, and doctoral student at the Vienna University for Economics and Business.

A major challenge in understanding community flood resilience is the lack of an empirically validated measure of it. To plug this gap the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance (ZFRA) developed the Flood Resilience Measurement for Communities (FRMC). In the first phase of the Alliance we applied the FRMC tool in 118 communities in nine different countries. This is what we learnt from it.

What is the Flood Resilience Measurement for Communities?

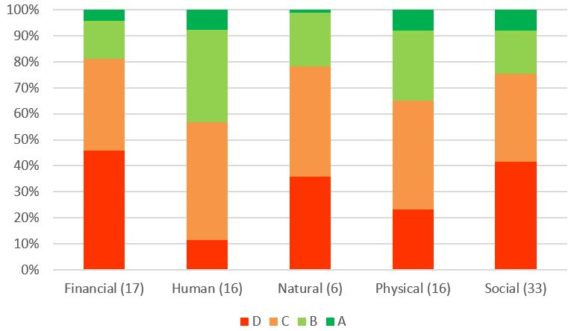

The FRMC approach holistically measures a set of “sources of resilience” before a flood happens (e.g. household savings or whether a community has a flood recovery plan) and looks at the post-flood impacts afterwards (e.g. level of loss and recovery time). The FRMC framework is built around the notion of five types of capital (the 5Cs: human, social, physical, natural, and financial capital) and the 4Rs of a resilient system (robustness, redundancy, resourcefulness, and rapidity). The data is collected and assessed via an integrated and hybrid platform. Each source of resilience is graded from A to D (best practice to significant below good standard) providing communities and decision-makers with an overview of the level of resilience capacity.

The 5 Capitals and 4 sources of resilience © Paulo Cerino

What did we learn from this large-scale analysis of community flood resilience?

Human and physical capital had the most sources assigned an A or B grade. The highest rated sources are education (value and equity), flood exposure perception, knowledge and awareness, communication, water, personal safety as well as health and sanitation. This could be a result of flood mitigation interventions traditionally being focused on building people’s skills and knowledge and/or physical structures.

Overview of frequency of grades for the sources of resilience by capital. Note: Number in bracket of capitals indicates the number sources in that capital. (Source: Campbell et al., 2019)

Despite the source-specific guidance and standardized data, grading is largely a judgment-based process and the FRMC includes a box where the assessor indicates how confident they are in the assigned grade. Since the trained assessors are practitioners with local understanding of the community the grades are influenced by their field expertise. The assessors were generally confident in the assigned grades and we found that their confidence increased the more data collection methods that were used.

Linking flood resilience and community characteristics

The FRMC was used in a range of different communities in developing and developed countries in contexts ranging from urban to rural and with some difference in past experience of flooding.

We discovered a correlation between poverty and lack of flood resilience and also found that having experienced very severe floods reduced a community’s level of resilience while experiencing frequent but less severe floods could help contribute to resilience, potentially by providing communities with relevant experience to adapt.

Does the FRMC process result in different interventions?

A key question we asked is whether the process of carrying out the baseline measurement and sharing results with the community resulted in interventions that were substantially different from what would have been implemented anyway. We find that it did, though to somewhat varying degrees.

Country teams overwhelmingly reported that the process helped them, their stakeholders, and communities to see flood resilience in a much more holistic way. For example, by broadening the perspective of flood resilience beyond that of physical infrastructure to also include social capital. The FRMC process influenced the implementation of a wide range of interventions, showing the breadth of the underlying conceptualization of resilience. The purpose of the FRMC approach is to help communities holistically strengthen their resilience and the broad range of interventions shows that this has worked.

Many country programs revised their project plans, log-frames and budgets as a result of the baseline measurement. Program staff highlighted how welcome it would be if other funders followed Zurich’s lead and allowed for similar in-depth analysis prior to intervention design and flexibility to act on the learning coming out of it to ensure the most effective intervention design.

What’s next for the FRMC?

This testing and data analysis has fed into the revision process for the development of the Next Generation FRMC which is currently being scaled to many more communities.

As the tool and measurement gets used in more communities and as part of more decision-making processes for flood resilient investments, we hope the usefulness and relevance of the tool will be demonstrated and adopted by many more organizations working to build community flood resilience.

Abel from Practical Action interviewing Consuelo, a community member in San Miguel de Viso, Peru as part of FRMC data collection ©Giorgio Madueño –

Reference:

Campbell KA, Laurien F, Czajkowski J, Keating A, Hochrainer-Stigler S, & Montgomery M (2019). First insights from the Flood Resilience Measurement Tool: A large-scale community flood resilience analysis. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 40: e101257. DOI:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101257. http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/id/eprint/16027/

Access available resources on the FRMC here.

This blog is reposted from a Flood Resilience Portal blog.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.