Aug 25, 2017 | IIASA Network, Sustainable Development

Johanna Mair is a professor of Organization, Strategy and Leadership at the Hertie School of Governance, Academic Editor of Stanford Social Innovation Review, Co-Director of the Global Innovation for Impact Lab at the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society, and Academic Co-Director Social Innovation and Change Initiative at the Harvard Kennedy School. Mair is also a member of the Alpbach-Laxenburg Group, which holds its annual retreat this weekend on the sidelines of the European Forum Alpbach.

Johanna Mair ©Hertie School of Governance

At the Alpbach-Laxenburg Group retreat this weekend, you will be joining a discussion on governance and institutional transformation towards sustainability. What do you see as the biggest barriers to sustainable development?

Sustainability challenges typically require a concerted effort to achieve impact. We still lack the appropriate governance and accountability mechanisms that ensure implementation of well-intended strategies and commonly devised goals.

As an expert in social entrepreneurship and innovation, what new developments have you seen that you think could drive a transformation towards sustainability? Could you give examples of successful innovations that have taken hold?

We do see innovation on many fronts. Especially in governance technology has enabled a number of useful and helpful innovations that allow for more transparent and accountable processes. At the same time we still face enormous challenges that cannot be fixed by technology and require us to face deeply rooted relational and cultural problems. The prevalence of open defecation and lack of sanitary infrastructure in India is just one example.

Sometimes it seems like there are many great ideas, but adoption is slow. What do you think is necessary to make the leap from innovative idea to widespread practice?

“Most new ideas are bad ideas” as Jim March from Stanford University would say. We must stop praising innovation and start to think and act on linking innovation and scaling as two distinct process to create impact. Innovation is an investment and creates the potential for impact. Scaling enacts and grows this potential and transforms innovation into tangible outcomes – improving the lives of marginalized people and communities and making progress on stubborn societal and environmental problems.

We have elaborated on this in our new book on “Innovation and Scaling for Impact – How Successful Social Enterprises Do It,” which I co-wrote with Christian Seelos.

How do innovation and governance go together? What are the challenges and opportunities for bringing new ideas into institutions and governments?

Governance needs to exert an enabling role. We need to craft and design governance systems that foster innovation. At the same time, governance systems need also make sure that the potential and usefulness of innovation can be tested along the way. This requires reflecting on markers of success that are process and not outcome focused.

The Alpbach-Laxenburg Group brings together leaders from business, and young entrepreneurs, along with government leaders and science experts. What do you think can be gained from a meeting of this type?

The most important outcome will be a shared understanding of priorities, pathways, and markers of success for this journey.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

More information

IIASA at the European Forum Alpbach 2017 and Alpbach-Laxenburg Group Retreat: 27-29 August 2017

Johanna Mair appearances at Alpbach: 19 August – 1 September

Sep 28, 2016 | IIASA Network

By Daniel McMurray, BA LLB MIL Global Event Lead – Impact Hub, Managing Director & Global Head of Communications – Enterprise IQ Pty Ltd

“It is paradoxical, yet true, to say, that the more we know, the more ignorant we become in the absolute sense, for it is only through enlightenment that we become conscious of our limitations. Precisely one of the most gratifying results of intellectual evolution is the continuous opening up of new and greater prospects”.

– Nikola Tesla

It is hard not to feel that we live at a pivotal moment in history, with the world racing toward an epochal crossroad.

In one direction lies the path of reason, science, community and progress. A world where growing systemic challenges like climate change, resource scarcity, overpopulation, inequality, and environmental degradation can be addressed through logic, evidence, and rational, creative, and collaborative action. Where the ingenuity, collective genius, and relentless optimism of humanity can resolve complex problems such as poverty, disease, and ecological collapse, creating abundance of energy, health, education and well-being for all.

In the other direction, lies a different path. One of regression, unreason, and parochialism. A fact-free, fearful and frightening world of separation, science denialism, and superstition, ruled over by demagogues offering glib, unworkable solutions, convenient scapegoats to blame, and soothing illusory retreat into fragmented tribal realms.

Which path we collectively choose to follow will determine the trajectory of the 21st century and beyond. Will we choose the enlightened path of working together collectively, collaboratively, and consciously for the greater good? Or will we choose the path of darkness, disintegrating into unconscious, unreasonable and irrational behavior that hastens systemic collapse?

At such a pivotal moment, the choice of “New Enlightenment” as the theme for the recent European Forum Alpbach was a timely, prescient and crucial framing.

Attending the forum with my European-based colleagues from Impact Hub – a globally connected network of social entrepreneurs, innovators, and change-makers as official partners for the event – inspired hope that the path of enlightenment, reason and collaborative action is fundamentally achievable.

Members of the Alpbach Laxenburg Group and Impact Hub hike in Alpbach, Austria in August 2016. © Matthias Silveri | IIASA

One of the highlights of the event for our contingent was a facilitated hike into the Tyrolean alps with Pavel Kabat (Director General & CEO of IIASA) and other key thought leaders from the Alpbach Laxenburg Group – including Jeffrey Sachs (Director of The Earth Institute from Columbia University), Tarja Halonen (the former President of Finland), Björn Stigson (former President of the WBCSD), Justin Yifu L in (Director of the Centre for New Structural Economics at Peking University), Pascal Lamy (former Director-General of the WTO), and many more cross-sectoral leaders from business, government, NGOs and civil society.

Gathered together in the scenic environs of the Boglalm Chalet, this diverse and eclectic group focused our discussion around how we can work together to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

Professor Sachs’ definition of an “entrepreneur” struck a chord. He described entrepreneurs as those with the vision to take elements from diverse sources, creatively combining and re- combining in new ways, key insights from different sectors, research fields, technologies, or existing systems to present a new solution or way of thinking.

In that group, representing a mix of the established elite and the challengers of tomorrow, the old and the new from business, government, science, social enterprise, and civil society, it was refreshing to feel the positive energy and inspired thinking that can come from embracing and making space for an open, cross -pollination of ideas.

It brought to mind a universal truth – that humanity is at its best when we work together collaboratively, breaking down barriers, dissolving silos of thought and entrenched interests and, like Professor Sachs’ concept of real entrepreneurship, combining ideas in new, innovative and creative ways. The path of enlightenment is not the domain of any one group. Political leaders can’t fix things alone – lacking the power, methodologies, community currency, and instruments required. They need business leaders, scientists, innovators, and change-agents from the social sector and civil society to bridge the gaps in dialogue, bring fresh insights and recombine them in radically new ways.

As Albert Einstein famously said, “We cannot solve our problems with the same level of thinking that created them”. The path of enlightenment can only be reached through collaborative action. It is a conscious choice and one that we must come together to choose in order to avert catastrophe.

“Really, the only thing that makes sense is to strive for greater collective enlightenment”.

Elon Musk

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Sep 4, 2017 | Science and Art

By Merlijn Twaalfhoven, composer, musician, entrepreneur, and member of the Alpbach-Laxenburg Group, which held its annual retreat last week on the sidelines of the European Forum Alpbach 2017 Political Forum.

Merlijn Twaalfhoven ©Merijn van der Vliet

Imagine you bring a group of people together, ask them to sit down, give them a drink and then pose the following question: how can we enact transformative social change towards enhanced sustainability and equity?

What would be the looks on their faces? Who would speak up? Last week, I happened to be present in such a group. We sat down, had a glass of water and started. None of us hesitated. We all brought our statements, relevant experience, passionate insights. Those with the task to structure the exchange begged us to find constraint, and called for more digestible sizes of our contributions.

It’s one of the most exciting places on Earth at the end of August: The Alpbach-Laxenberg Group brings scientists, politicians, business leaders, and other experts together for three days of deep conversations about today’s most urgent challenges. It was a tremendous privilege to travel to this beautiful mountain village, join these wonderful people and discuss the future of our planet.

We could hardly breathe. Our conversations tumbled over each other, from the future of computer technology to publication frenzy in academia, from ecological farming in Egypt to outreach of art in Brussels. I could see the pieces of world’s jigsaw coming together. It became apparent that we have the knowledge, the insights, and the technology that’s needed for a sustainable world. We might even find investments, governmental support, or access to the most influential circles at the WTO or the UN. We felt how currents of knowledge start to flow when all these wires connect.

But on way back to the lowlands, the mountains slowly disappearing in my train window, I felt ambivalent.

Did we discuss the right questions? I saw so much strength. Strong voices, strong ideas. Hard data, clear evidence. But we almost drowned in ideas, visions, and possibilities.

The question that we did not pose was: what is our weakness? We are comfortable with wicked problems, global strategies, and impactful solutions. But can we perceive our own frailty? Do we have a sense of the limitations of our knowledge?

A mountain village is the best place to take a breath. To inhale fresh air. I’m afraid we exhaled too much. It was no doubt valuable emanation. We couldn’t stop giving answers. But we missed the opportunity to find better questions. I had the feeling we gathered as experts to play Jeopardy! against computer Watson. We battled to answer any question.

But is this our most effective role? Who has more influence: the person giving an answer or he or she who can formulate the question? In posing questions lies our ability to connect knowledge to curiosity. Any good story will have a captivating query at its base. Only when we can make a strong case for sustainability, can we mobilize our society to become involved.

When a child is missing, the whole village wakes up to search. When will our global village wake up and unite to fight for a sustainability revolution? What might be the most activating murder case that can bind us and make us embark on a heroic quest?

Last days in Alpbach, it was like musicians joining together. We unpacked our instruments and tuned our strings. It was a wonderful sound indeed. We resonated. But this was not yet the performance. The audience is waiting – distracted by their smartphones – until the moment we start truly playing together and deliver a story that’s tremendous, enchanting and mesmerizing.

Alpbach-Laxenburg Group members debating on Monday 28 August, 2017. From left to right: Hermann Hauser, Partner at Amadeus Capital Partners Ltd., Jeff Sachs, Director of The Earth Institute at Columbia University and IIASA Distinguished Visiting Fellow, Merlijn Twaalfhoven Composer and Cultural Entrepreneur, Amsterdam, Gloria Benedikt, dancer, choreographer, and Associate for Science and Arts at IIASA, and Milena ´ic Fuchs, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Zagreb; former Minister of Science and Technology of Croatia. © Patrick Zadrobilek | IIASA

Merlijn Twaalfhoven

Composer, musician, enterpreneur.

UNESCO prize (2011).

Working on What Art Can Do – a collection inspiring examples of the work of artists around 17 Sustainable Development Goals.

http://merlijntwaalfhoven.com

http://whatartcando.org

https://twitter.com/Merlijn12H

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 10, 2016 | Alumni, Demography, Young Scientists

by Julia M. Puaschunder, alumna of the IIASA Young Scientist Summer Program 2016.

The world is on the move. Currently, more than 250 million people live outside their countries of birth. Of the moving masses, an estimated 6% are refugees fleeing across borders to more favorable environments. The ongoing European refugee crisis has increased the pressure to reap the benefits from migration while alleviating the burdens of societal movement.

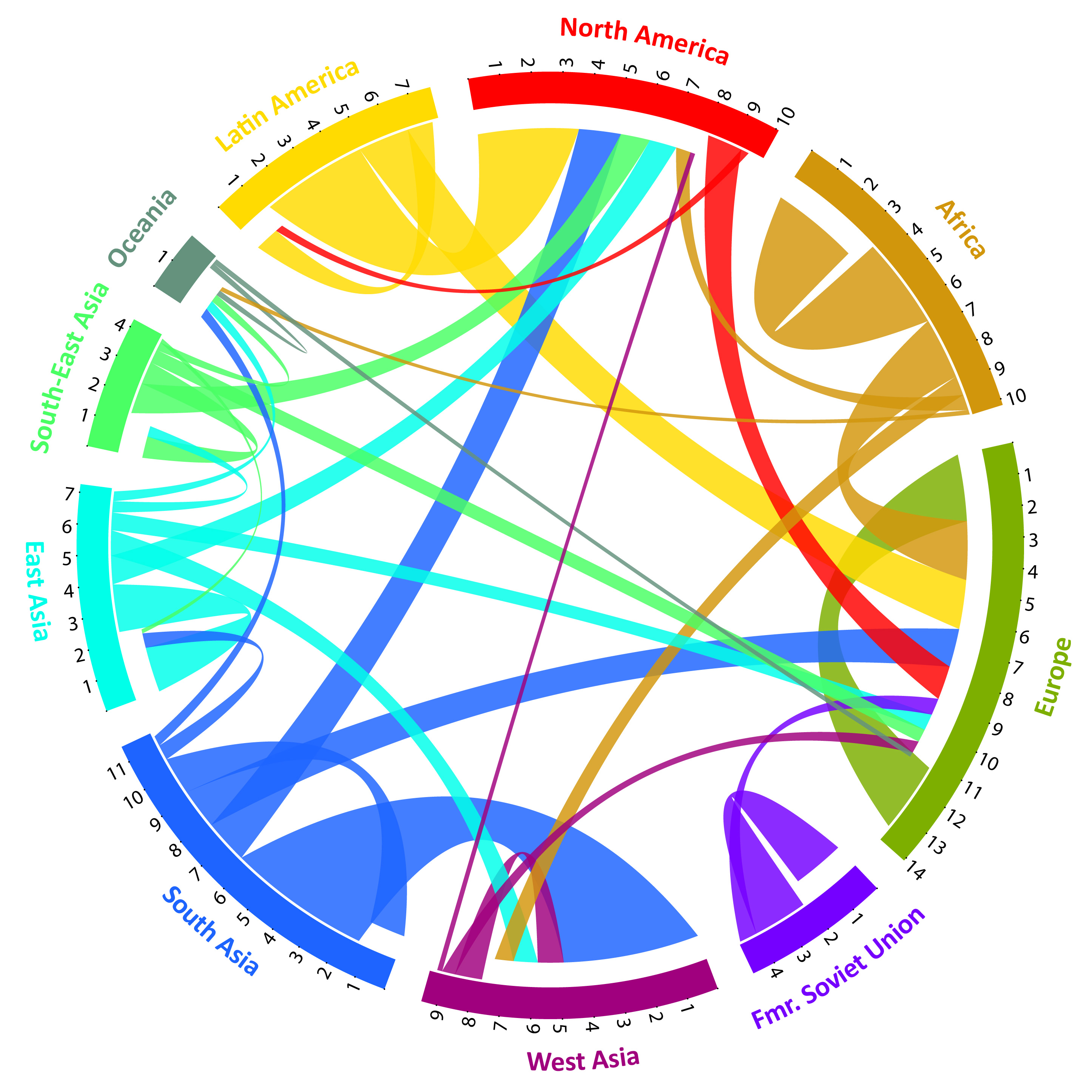

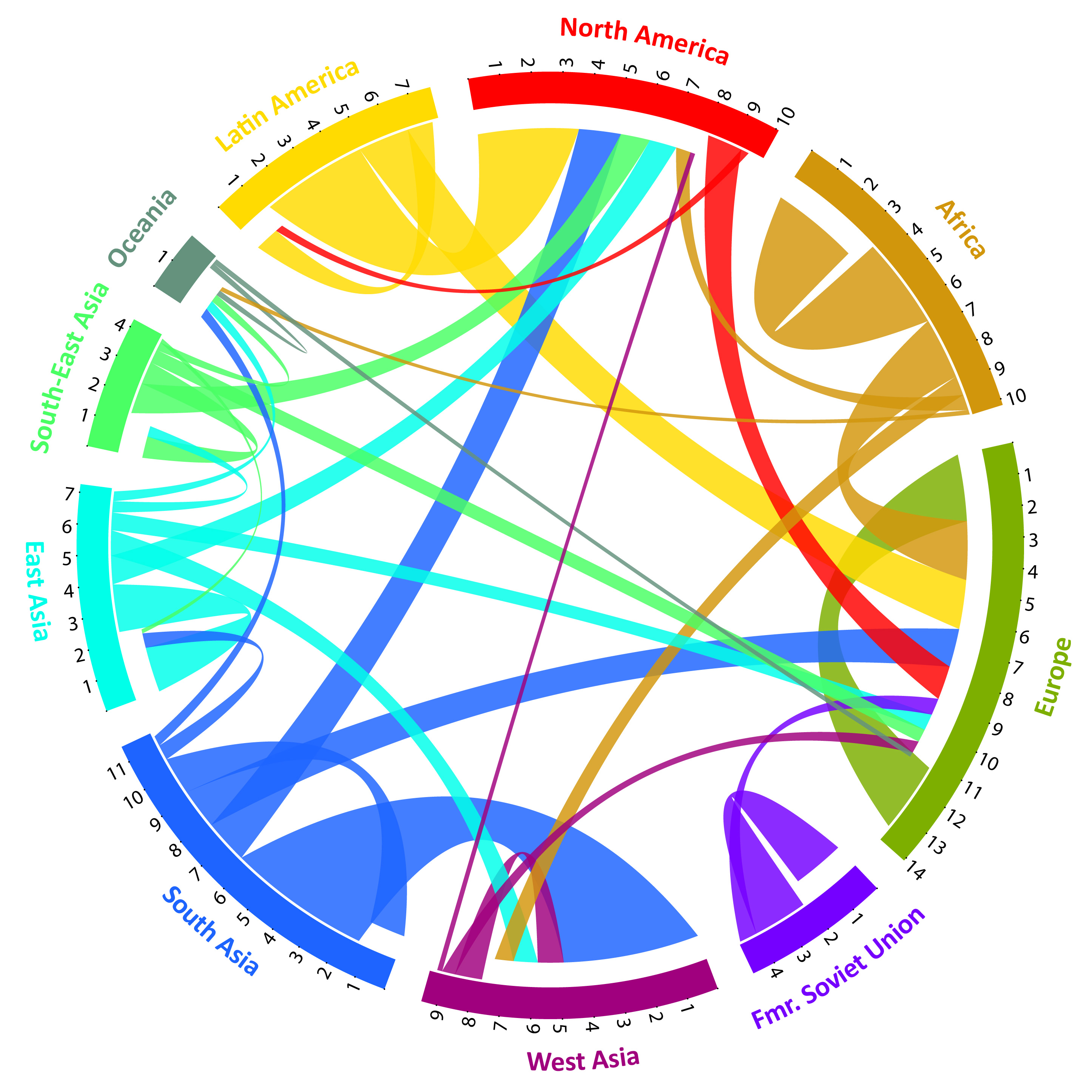

Estimates of directional flows between 123 countries between 2005-2010. Only flows containing at least 50,000 migrants are shown. “The Global Flow of People” (www.global-migration.info) is by Nikola Sander, Guy Abel & Ramon Bauer, and published in Science as “Quantifying global international migration flows” in 2014 (vol. 343: 1520-152).

Concerns were recently raised as to whether granting asylum to refugees—who often make up the most productive parts of their original populations—prevents (re)development in their fractionated home countries? An important consideration absent in these debates are the monetary gifts migrants send to their family members back home.

The World Bank estimates that migrants currently return around 450 billion US Dollars per year to the developing countries they came from, and this number is expected to rise. These monetary remittances have multiple positive impacts, including economic growth. As refugees are primarily younger to middle-aged, their remittances likely pay for their wives and children’s access to medical care and education, or support their parents when pension systems are missing.

Intergenerational monetary transfers are therefore the focus of my recent publication Gifts Without Borders. Contrary to conventional institutionalized sustainable development, remittances grounded in intergenerational care benefit from communication within families. Long-lasting family ties allow direct feedback. People truly care about their loved ones back home and families share their day-to-day experiences honestly. Intergenerational remittances beyond borders are thus a purer and potentially longer-enduring pathway to sustainable development, as these stable funding streams’ impact is more accountable than standard international aid.

Based on World Bank and OECD data covering almost all countries of the world, my forthcoming publication in the book ‘Intergenerational Responsibility in the 21st Century’ highlights that the intergenerational glue of a migrating population helps countries lacking socially responsible and future-oriented public sectors. Rather than blaming asylum-granting countries for removing the labor force from fragile territories, hosting refugees is portrayed as making use of human capital in stable economies, while refugees—at the same time—develop their former homelands by direct monetary contributions in a natural, transparent, and accountable way. In the age of migration, analyzing intergenerational networks and their financial flows is an important, but unexplored, facet of sustainable development. My findings open prospective research avenues on how we can align the economic outcomes of human capital mobility with sustainable development.

The IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program granted a vibrant setting to discuss my findings in a group of international, diverse, and multi-disciplinary future academic leaders during this summer, which was filled with beautiful moments in the historic Schloss Laxenburg in Austria. Recently IIASA also launched a Joint Research Centre of Expertise with the European Commission on Population and Migration, which aims to predict how migration will impact future economies and societies. In addition, the Advanced Systems Analysis (ASA) Program hosts the ‘Economic migration, capital flows, and welfare’ collaboration between ASA and the World Population Program to model dynamics of economic migration and investment. This research is also directly related to my New School Economic Review paper ‘Putty Capital and Clay Labor: Differing European Union Capital and Labor Freedom Speeds in Times of European Migration,’ which elucidates trade differences in capital and labor flows gravitating the benefits and burdens of globalization unequally and the potential problems arising for the European project from migration.

The Alpbach-Laxenburg Group Retreat 2016 on New Business Models for Sustainable Development. © Matthias Silveri | IIASA

Above all, attending the IIASA 2016 Alpbach-Laxenburg Group Retreat at the European Forum Alpbach helped to enhance my understanding of the relationship between migration and intergenerational responsibility. All these endeavors are targeted at contributing to sustainable development in a world on the move.

More information on the author of the post: www.juliampuaschunder.com

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 30, 2016 | Sustainable Development

Michael Perkinson is the chief of staff to the chief investment officer at the asset management firm Guggenheim Partners in the US. On 28 and 29 August he took part in a meeting of the Alpbach-Laxenburg Group, focused on new models for sustainable business development, and on 30 August he spoke at the European Forum Alpbach Political Symposium.

Michael Perkinson speaks at the European Forum Alpbach. ©Matthias Silveri | IIASA

As a business leader with a background in international relations, you have unique experience in both government and the private sector: How do you think that the two could work together towards achieving the sustainable development goals?

Traditionally, the two sectors have not mixed well. Governments were skeptical of the private sector’s profit motives and the private sector believed government was an impediment. Both views were, of course, short-sighted. In recent years the United Nations has looked to the private sector to help finance development as the traditional levels of fiscal policy have been removed from the toolkit by increasingly narrowly focused legislatures. Similarly, private investors and private enterprise, who make up over 60% of GDP in the developed world, realize that they can partner with governments to achieve their social goals. Yes, businesses now have social goals.

What do you see as the biggest challenge is in achieving the SDGs?

Money and willpower.

What changes would be needed in business in order to fully embrace the SDG agenda?

I suspect that businesses need to understand how they can contribute. If given the option of a regulation or a tax, businesses will always chose a tax, because it allows them to plan accordingly. So, in this case, I think businesses require an explanation as to how they can contribute and how it won’t interfere with their executing on their business plan.

Business is often seen as “part of the problem” when it comes to issues like climate change and poverty – do you think that sustainable development could also bring opportunity for business, and if so, how?

Having been in the public sector for 25 years before returning to the private sector, I have never seen the private sector as part of the problem. In the United States, the private sector contributes some 80% of GDP. The private sector also provides jobs, which is really the only way that poverty can be eliminated on a generational scale. I think that there is ample opportunity for business to contribute to the SDGs, but the public sector needs to explain clearly how businesses can contribute in a way that doesn’t interfere with their business plan. It doesn’t mean that businesses need an inducement (like a tax break), they just need to understand the strategic logic of the concept.

Meeting of the Alpbach-Laxenburg Group, 29 August 2016. ©Matthias Silveri | IIASA

Interview conducted and edited by Katherine Leitzell, IIASA science writer and press officer

Note: This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.