By Anastasia Aldelina Lijadi, research scholar in the IIASA World Population Program

What does happiness mean? The concept of “happiness” has somewhat abstruse meanings in different languages. Some suggest the idea of luck or good fortune (German, Norwegian, French, Korean, Russian, Japanese, Chinese) and others intimate satisfaction of one’s desires or wishes and goals and enjoyable experiences (Italian, Portuguese, Spanish). Anthropologists, economists, linguists, psychologists, sociologists, and other researchers from various disciplines are still struggling to operationalize the concept, and ensure that enhanced quality of life is a realistic and obtainable goal for human kind.

As part of the project Empowered Life Years, at the World Population Program at IIASA, the concept of happiness has been identified as one of the conditions for sustainable human wellbeing, along with health, literacy, and being out of poverty. Being the newest in the team, I was privileged to attend the 15th annual conference of International Society for Quality-of-Life Studies (ISQOLs) to attend lectures and presentations and better comprehend the concept of happiness and how this research-based knowledge can contribute to people’s wellbeing.

Six supports for happiness

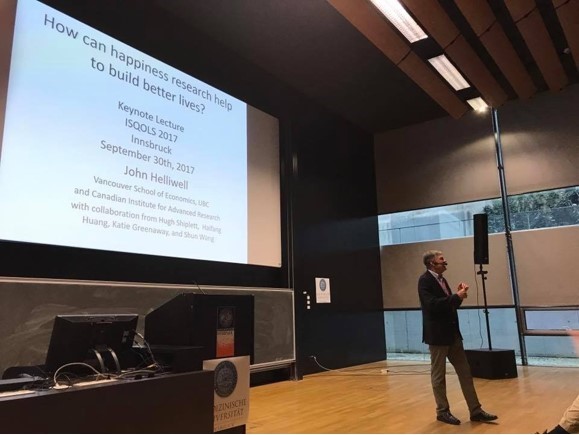

The distinguished keynote speaker Prof. John F. Helliwell specified six prerequisites for a human being to be happy, which are material (such as food and shelter), relationships, mental and physical health, freedom from oppression, generosity, and trust. His studies showed that mental and physical health is more effective in increasing happiness than raising income or ending unemployment. Moreover, people are more generous (i.e., show strong altruism or pro-social behavior such as donating blood, or care for environment) when they have a good social relationships within their community.

Keynote lecture at the ISQOLs conference. © Anastasia Aldelina Lijadi | IIASA

Measuring Happiness beyond GDP: How and for whom?

It is hard to tell what does cause (un)happiness in a country when wealth has failed to fully explain it. The Easterlin Paradox claims that a society’s economic development and its average level of happiness are not linked beyond a certain level of income that satisfies basic needs. This is the case in Latin America, as Prof. Mariano Rojas, president of ISQOLs, pointed out in his presentation. Bhutan also fits this theory, said Prof. Shrotyia Vikar Kumar of the University of Delhi, as it has controversially the highest happiness index in the world despite low GDP.

In addressing income inequality, Prof. Richard Wilkinson of the London School of Economics, stressed that the story is the same in unequal societies worldwide: men in poorer households feel low, outcast, and very sensitive to what others think about them, wives loathe their husbands, and children ashamed of their condition. We witness a higher discrepancy in health, crime, infant mortality, and civic participation between rich and poor communities. The rich also rate themselves better than poorer people, and are more likely to search for ‘status goods’ in google!

Prof. Antonella Delle-Fave, University of Milan, urged us to review the construct of happiness before trying to measure it. She also criticized the polarizing and overused concepts of hedonic and eudemonic happiness. Hedonic happiness is based on the experience of pleasure or positive feelings while generally avoiding any painful experiences. Eudemonic happiness is the notion of wellbeing based on the pursuit of personal fulfillment and realizing one’s potential by engaging in meaningful activity. Delle-Fave found that many researchers use a mix of variables derived from both concepts.

Prof. Richard Layard, author of Happiness: Lessons from a New Science, stated that happiness evolves over the life course. A simple cross-sectional correlation study cannot explain the evolution of happiness throughout life course, and Layard urged future research to employ an interdisciplinary approach to find the determinants of happiness. This will help policymakers to create meaningful, accessible, and age-sensitive opportunities for promoting quality of life throughout a lifetime.

Prof. Delle-Fave added that bottom-up qualitative research is needed to define happiness, eliciting voices directly from the source: “After learning from university, we need to learn from people.” I will use this powerful yet simple advice in my work on Empowered Life Years at IIASA.

Note: This article gives the views of the author and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Very interesting topic for discussion. Everyone has his own concept of happiness. Family, work, self-development, travel each person chooses how to be happy. I am happy from the fact that I work on the work of my dream, I write texts for students on EssayViking. I consider this my vocation. I love my family and my work.