By Caroline Njoki, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2017

Wealthier regions with high population densities have the largest influxes of non-native species, a new study has found. This is mainly because of global trade and strong transport links, the researchers concluded.

Researchers assessed global patterns from 609 regions consisting of 186 islands and 423 mainland regions. Using available global and national databases as well as a thorough literature search for eight taxonomic groups (vascular plants, birds, freshwater fishes, ants, spiders, amphibians, mammals and reptiles), they identified hotspots with high and low diversity of non-native species. Socioeconomic and environmental factors such as climate were also taken into consideration.

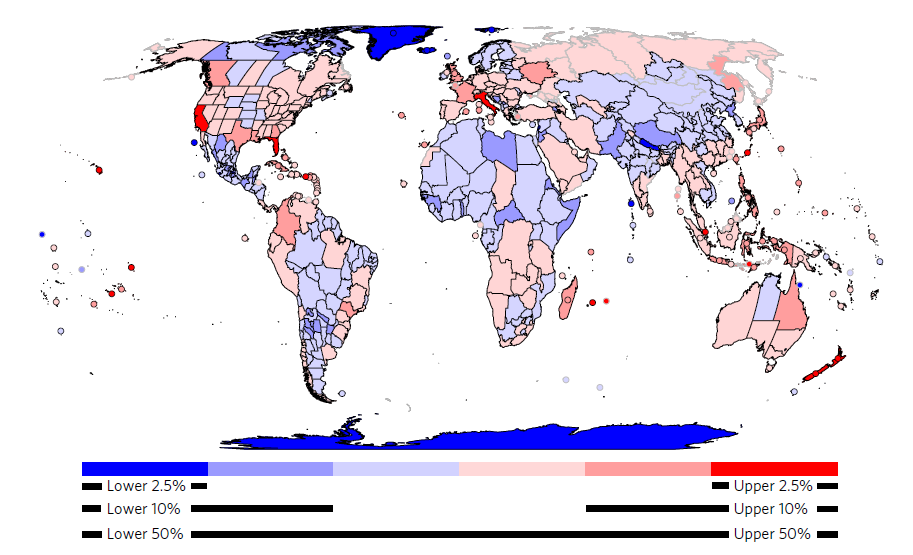

Map showing hotspots with high (dark, medium and light red) and low (dark, medium and light blue) diversity of non-native species across the eight taxonomic groups. Source: Dawson W et al. (2017).

The results indicate that remote and highly populated islands, developed countries, and nations with fast growing economies have the greatest influxes of invasive species from across the taxonomic groups due to reliance on foreign commodities. This also applies to coastal regions that have seaports serving as import hubs for non-native birds and aquatic organisms. The rate of invasion is especially high on islands and in coastal regions with warmer climates.

Native, endemic, and rare plants and animals could be particularly vulnerable in these regions, especially if the absence of predators or reduced numbers of competitors on islands allows invasive species to thrive. Under climate change, urbanization, and land-use intensification, non-native species might also be able to increasingly spread into environments that were previously unviable for them.

‘‘Horticultural products from other regions are among the commodities accounting for a large influx of non-native plants and arthropods (spiders), especially in Europe and North America,” said coauthor of the study Bernd Lenzner, a PhD student at the University of Vienna and a participant in the IIASA Young Scientist Summer Program.

Lenzner’s work at IIASA to predict future patterns up to year 2050, is critical to help guide development of appropriate strategies to tackle species such as the Hottentot fig (seen here with purple flowers) originally from South Africa but invasive in Mediterranean coastal habitats © Bernd Lenzner | IIASA

Several regional initiatives enabling the public to participate in monitoring and reporting of invasive species through user-friendly digital applications exist, like the “Invasive Alien Species Europe” app. This contains photos and fact sheets of a number of species that have become invasive in Europe to allow users to identify and submit information regarding occurrences of species of concern.

Lenzner’s current work at IIASA is to develop models indicating likely future patterns of invasive species at a global scale by integrating data from several models, including the IIASA Global Biosphere Management Model. Construction of the models is based on information collated from climate change, population dynamics, the resilience of native biodiversity, legislation, trade, transport activities, and land-use and land-cover change. The research will provide predictions up to the year 2050, to guide policymakers to develop appropriate strategies to tackle non-native species.

To ensure wider applicability, the work is linked to the IIASA-led Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs). The SSPs provide alternative explanations on how various elements, such as governance, urbanization, and economic growth, might develop in the future. Some of these factors will have crucial impacts on the displacement and establishment of non-native species.

“Forecasting future scenarios, though necessary, may be hindered by uncertainty over the probable impacts, and scattered and insufficient data. This is further complicated by a lack of a clear definition of invasive species. More funding and research effort are required to generate comprehensive information vital for effective management of invasive species if the Aichi Target 9 by the Convention on Biological Diversity is to be realized by year 2020,” says Lenzner.

Nile perch was introduced to Lake Victoria, East Africa for its beneficial traits but has eliminated many native fish © Fotogien | Shutterstock

Global trade has developed rapidly, with advances in transport enabling easier and faster movement of goods and people in high volumes. The rising human population also drives the demand for commodities. This global trade network opens the door for species to spread across the world. In addition, non-native species are sometimes deliberately or accidentally introduced, often in the form of ornamental, agricultural, and forestry products, or because of research, natural disasters, and the pet trade.

“Some countries introduce species for their beneficial traits without conducting proper risk assessments, only to suffer from the resulting impacts later on. For instance, Nile perch in Lake Victoria, East Africa has eliminated many native and endemic fish. It takes a while for certain introduced species to exhibit invasive characteristics as they adapt to their new environment or conditions become more favorable,” said Lenzner.

The findings are important, especially for countries at greater risk of invasion, to help policymakers put measures in place to stop further introductions and the spread of non-native species. The move aims to safeguard human health, economies, infrastructure, native organisms and associated environmental goods and services.

About the researcher

Bernd Lenzner is a third year PhD student at the Division of Conservation Biology, Vegetation and Landscape Ecology at the University of Vienna. His research focuses on understanding spatial and temporal patterns and processes of global naturalized alien plant species richness and assembly. At IIASA, Bernd is working with the Ecosystem Services and Management Program to develop the first global scenarios for biological invasion in the 21st century under the supervision of David Leclère and Oskar Franklin.

References

Dawson W, Moser D, Kleunen M & Kreft H et al (2017). Global hotspots and correlates of alien species richness across taxonomic groups. Nature Ecology and Evolution 1: 0186

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.