Jul 26, 2017 | Alumni, Climate Change, Poverty & Equity, Sustainable Development, Water, Young Scientists

Adil Najam is the inaugural dean of the Pardee School of Global Studies at Boston University and former vice chancellor of Lahore University of Management Sciences, Pakistan. He talks to Science Communication Fellow Parul Tewari about his time as a participant of the IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) and the global challenge of adaptation to climate change.

How has your experience as a YSSP fellow at IIASA impacted your career?

The most important thing my YSSP experience gave me was a real and deep appreciation for interdisciplinarity. The realization that the great challenges of our time lie at the intersection of multiple disciplines. And without a real respect for multiple disciplines we will simply not be able to act effectively on them.

Prof. Adil Najam speaking at the Deutsche Welle Building in Bonn, Germany in 2010 © Erich Habich I en.wikipedia

Recently at the 40th anniversary of the YSSP program you spoke about ‘The age of adaptation’. Globally there is still a lot more focus on mitigation. Why is this?

Living in the “Age of Adaption” does not mean that mitigation is no longer important. It is as, and more, important than ever. But now, we also have to contend with adaptation. Adaptation, after all, is the failure of mitigation. We got to the age of adaptation because we failed to mitigate enough or in time. The less we mitigate now and in the future, the more we will have to adapt, possibly at levels where adaptation may no longer even be possible. Adaption is nearly always more difficult than mitigation; and will ultimately be far more expensive. And at some level it could become impossible.

How do you think can adaptation be brought into the mainstream in environmental/climate change discourse?

Climate discussions are primarily held in the language of carbon. However, adaptation requires us to think outside “carbon management.” The “currency” of adaptation is multivaried: its disease, its poverty, its food, its ecosystems, and maybe most importantly, its water. In fact, I have argued that water is to adaptation, what carbon is to mitigation.

To honestly think about adaptation we will have to confront the fact that adaptation is fundamentally about development. This is unfamiliar—and sometimes uncomfortable—territory for many climate analysts. I do not believe that there is any way that we can honestly deal with the issue of climate adaptation without putting development, especially including issues of climate justice, squarely at the center of the climate debate.

COP 22 (Conference of Parties) was termed as the “COP of Action” where “financing” was one of the critical aspects of both mitigation and adaptation. However, there has not been much progress. Why is this?

Unfortunately, the climate negotiation exercise has become routine. While there are occasional moments of excitement, such as at Paris, the general negotiation process has become entirely predictable, even boring. We come together every year to repeat the same arguments to the same people and then arrive at the same conclusions. We make the same promises each year, knowing that we have little or no intention of keeping them. Maybe I am being too cynical. But I am convinced that if there is to be any ‘action,’ it will come from outside the COPs. From citizen action. From business innovation. From municipalities. And most importantly from future generations who are now condemned to live with the consequences of our decision not to act in time.

© Piyaset I Shutterstock

What is your greatest fear for our planet, in the near future, if we remain as indecisive in the climate negotiations as we are today?

My biggest fear is that we will—or maybe already have—become parochial in our approach to this global challenge. That by choosing not to act in time or at the scale needed, we have condemned some of the poorest communities in the world—the already marginalized and vulnerable—to pay for the sins of our climatic excess. The fear used to be that those who have contributed the least to the problem will end up facing the worst climatic impacts. That, unfortunately, is now the reality.

What message would you like to give to the current generation of YSSPers?

Be bold in the questions you ask and the answers you seek. Never allow yourself—or anyone else—to rein in your intellectual ambition. Now is the time to think big. Because the challenges we face are gigantic.

Note: This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Dec 15, 2015 | Demography

By Raya Muttarak, IIASA World Population Program

This blog was previously posted on the GMR’s World Education Blog

Not only have climate scientists agreed that humans are contributing to climate change, but recent evidence also points out that the rate of warming is happening much faster now than it ever has before. This is why, at the UN Climate Conference in Paris this month, world leaders sought to reach a new international agreement on climate change, essentially to keep global warming below 2°C (or 3.6°F). Rising temperatures pose threats on food and water security, infrastructure, ecosystems and health and, as a previous blog on this site shows, increases the risk of conflict. With an upsurge in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events and the potential for rapid sea level rise, both mitigating human-related exacerbation of climate change, and adapting to its devastating effects are key priorities. This is where education comes in.

Both mitigation and adaptation require technological, institutional and behavioral responses. Correspondingly, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change highlighted the value of a mix of strategies to protect the planet, which combine policies with incentive-based approaches encompassing all actors from the individual citizen, to national governments and international communities. Because, while national and sub-national climate action plans are fundamental, changing individual behaviour also lies at the heart of responses to climate change.

At the individual level, barriers to the adoption of mitigation and adaptation measures include a lack of awareness and understanding of climate change risk, doubt about efficacy of one’s action, lack of knowledge on how to change behavior and lack of financial resources to implement changes. Accordingly, there are many sound reasons to assume that different education strategies can help overcome these barriers both in direct and indirect manners.

First, directly formal schooling is a primary way individuals acquire knowledge, skills, and competencies that can influence their mitigation practices and adaptation efforts. Schooling provides a unique environment to engage in cognitive activities such as learning to read, write, and use numbers.

Students in Indonesia learn about living with nature. Credit: Nur’aini Yuwanita Wakan/EFAReport UNESCO

As students move to higher grades, cognitive skills required in school become more progressively demanding and involve meta-cognitive skills such as categorization, logical deduction and cause and effect. This abstract cognitive exercise alters the way educated individuals think, reason, and solve problems. Indeed, experimental studies have shown that higher-order cognition improves risk assessment and decision making. These are relevant components of reasoning related to risk perception and making choices about mitigation and adaptation actions.

Furthermore, education enhances the acquisition of knowledge, values and priorities as well as the capacity to plan for the future and allocate resources efficiently. Schooling can help individuals adopt, for instance, disaster preparedness measures by improving their knowledge of the relationship between preparedness and disaster risk reduction. Moreover, educated individuals may have better understanding of what measures to undertake. Recent evidence also shows that education can change time preferences such that more educated people are more patient, more goal-oriented and thus make more investments (e.g., financial, health or education investments) for their future. Such forward-looking attitudes can influence adoption of mitigation actions or adaptation measures where benefits may only be expected by future generations.

Apart from the direct impacts, education may indirectly reduce vulnerability or promote mitigation actions through other means. Firstly, education improves socio-economic status as education generally increases earnings. This allows individuals to have command over resources such as purchasing costly disaster insurance, living in low risk areas and quality housing, installing renewable energy sources at home or being willing to pay carbon taxes.

Secondly, many empirical studies have shown that people with more years of education have access to more sources and types of information. The level of education is not only highly correlated with access to weather forecasts and warnings but the more educated are better able to understand complex environmental issues such as climate change than less educated counterparts.

Knowing where to get information on how to reduce emissions or what adaptations to take allows individuals to change their behaviour appropriately. Indeed, there is evidence that good understanding of climate change or environmental knowledge are associated with climate change mitigation behaviours such as consumption of climate-friendly food, owning fuel-efficient vehicles and conservation behaviour.

In addition, more educated individuals also have higher social capital. A perception of risk and motivations to take preventive action are more likely to be communicated via social networks and through social activities. Evidently, through increasing socio-economic resources, facilitating access to information and enhancing social capital, education can promote and foster sustainable lifestyle and consumption.

Despite these potential benefits on climate action, education has not yet been sufficiently prioritized as a fundamental instrument to fight climate change. Recently researchers at the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital based in Vienna have produced convincing empirical evidence that education, particularly (at least) secondary school, is important for reducing vulnerability to climate change. By showing that education enhances disaster responses, reduces loss and damage and facilitates recovery after disasters, it was argued that part of Green Climate Fund should be spent to promote universal secondary education.

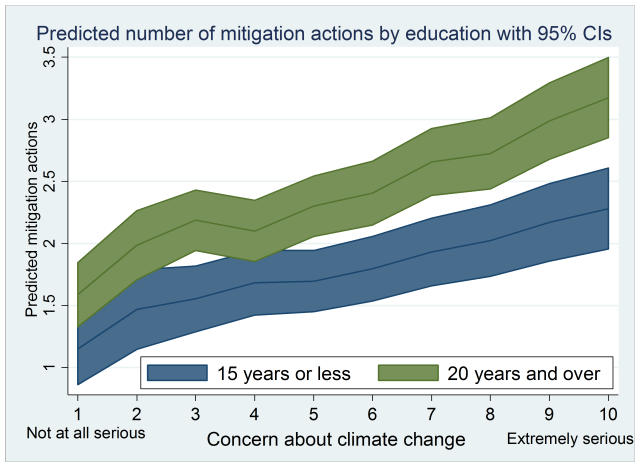

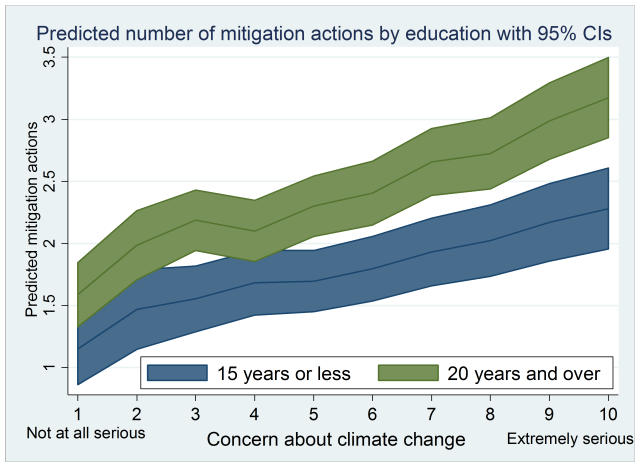

Likewise, education has also been shown to be an important determinant of sustainable lifestyle and consumption. As another blog on this site has shown recently, individuals with a higher level of education are more likely to be concerned about climate change and consequently more likely to take actions to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The Figure below clearly demonstrates how the number of mitigation actions increases with years of schooling. Not only do the highly educated carry out more mitigating actions, education also interacts with concern about climate change. In other words, given the same level of concern about climate change, the highly educated are doing even more to reduce GHG emissions than those with lower education.

Figure 1: Number of mitigation actions taken by years of schooling and concern about climate change

Notes: Own calculation. Estimated from multilevel models with country random effects. Source: Pooled Eurobarometer Surveys (2008, 2009, 2011, 2013).

Responding to the challenges of climate change is going to require action on multiple fronts. Ignoring the impacts of education on climate change is no longer an option. Promoting universal secondary education should be given a high priority on the agenda as we look forward past last week’s Paris meeting.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 30, 2015 | Climate Change, Risk and resilience

By Thomas Schinko and Reinhard Mechler, IIASA Risk, Policy and Vulnerability Program

Discussions on dealing with the already palpable as well as future burdens from climate change have moved into the spotlight of international climate policy. They are being tackled as part of the climate negotiations via the Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM) for Loss and Damage associated with Climate Change Impacts (Loss and Damage Mechanism), a measure for dealing with impacts and adaptation related to extreme climate events and slow onset events that was agreed in 2013. Debate on the scope, framing and on how the mechanism will eventually be implemented is still continuing, and is heavily framed around moral issues such as compensation, liability, and a need for attributing disasters to climate change, which is a difficult and complex issue.

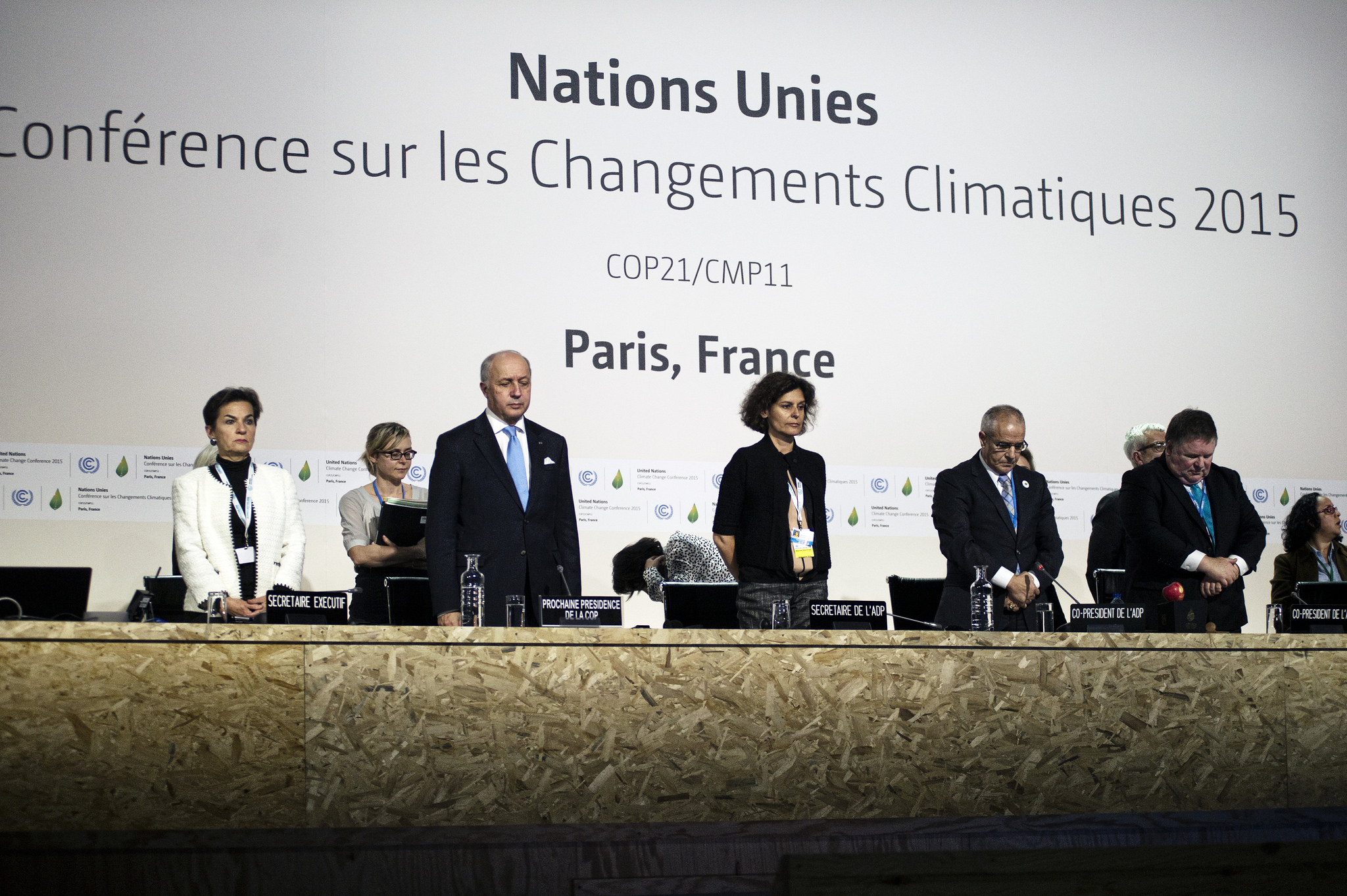

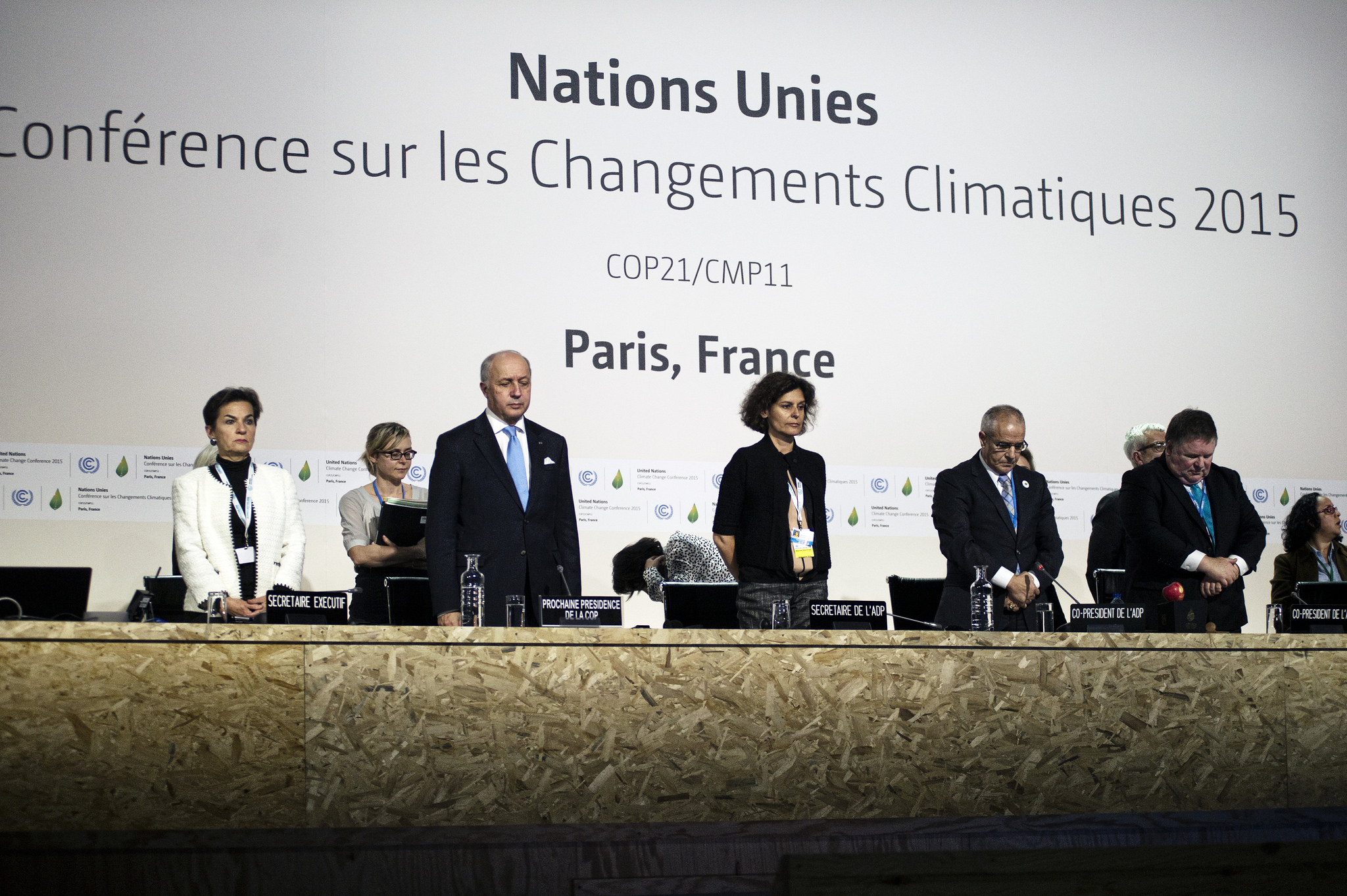

Opening of COP 21 on 29 November 2015. Photo: Benjamin Géminel via Flickr

To help move this contentious debate forward, we recently organized a meeting at IIASA to set up a broad scientific network to support work under the Loss and Damage Mechanism with rigorous and evidence-based research.

Since the first climate negotiations, climate justice has been a major source of contention, with countries disagreeing on the level of responsibility for climate change and the extent to which developed and developing countries should contribute to the solutions. These discussions have predominantly focused on climate mitigation responses, but over the last few years, impact and risk issues have moved into the limelight.

Discussions in the run-up to the 21st Conference of the Parties to the Climate Convention (COP 21) in Paris make it clear that answering key questions revolving around climate justice and climate finance will be pivotal for the conference to deliver on any global climate change agreement.

Even though some rich countries currently appear to acknowledge the central role of a mechanism covering losses and damages within a new global climate agreement to be negotiated at COP 21 in Paris, huge reservations remain. With changing climates, extreme weather events are likely to increase in frequency as well as in intensity. The global North fears exposure to soaring claims for financial compensation by countries of the global South, which will be facing the most severe risks from climate change. In fact, even the meaning and nature of Loss and Damage is still being debated – some suggest the Loss and Damage mechanism should be part of adaptation, while others want it to focus on residual risks that remain after adaptation efforts have been taken. For example, it could finance potential climate-induced migration.

Discussion of compensation raises complex issues about liability, and would presumably require attribution of losses and damages to emitters. Indeed, climate science has been making great progress in attribution research. Recent work has shown a significant human element in mega-events such as superstorm Sandy in 2013 in the US or the Australian heatwave in 2013. Yet, as our kick-off meeting reconfirmed, linking anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions to extreme weather events and to risks for people and property will remain extremely complex, not least as risks from climate-related events are shaped by many factors, including climate variability, rising exposure of people and assets, as well as socio-economic vulnerability dynamics. While the basic case for climate justice has been made, the concrete, enforceable case remains much harder to establish.

A protest for “climate justice” at Quezon City, Philippines on 14 November 2015. Photo: RB Ibañez via Flickr

For these good reasons and to not derail the debate by fixating on questions regarding liability, the debate has extended beyond the narrow focus on compensation – the omnipresent elephant in the room of the UNFCCC process. The meeting at IIASA, which brought together 14 researchers from 10 institutions and 8 countries, also suggested that for a productive discussion, it makes sense to focus broadly on managing various climate risks by fostering current policies and practices while keeping the climate justice debate in close consideration.

This proposal essentially suggests to build on a long history of managing climate-related (and geophysical driven) extremes by employing a broad portfolio of different disaster risk management tools, including financial instruments such as insurance or regional risk pools. As identified also by the IPCC’s 5th assessment report, building on this body of knowledge and practice for comprehensively tackling existing and increasing extremes, holds a lot of promise and has seen international support, e.g. by the Sendai Framework for Action.

The discussion at IIASA focused on these two angles – climate justice and climate risk management – and worked out the following specific foci and building blocks for an evidence-based research approach to support the operationalization of the Loss and Damage Mechanism:

- Articulation of principles and definitions of Loss and Damage, including ethical and normative issues central to the discourse (e.g. liability and responsibility).

- Definition of the Loss and Damage space vis-á-vis the adaptation space.

- Research on the politics and institutional dimensions of the debate.

- Defining the scope for dealing with sudden-onset risk versus slow-onset impacts.

In the coming months the novel network effort will tackle these issues and questions in order to provide actionable but research-based input into the Loss and Damage deliberations.

Note: The authors thank the researchers present at the kick-off event at IIASA for their input on the topic and this blog post: Florent Baarsch (Climate Analytics, Berlin), Laurens Bouwer (Deltares, Delft), Rachel James (University of Oxford), Stefan Kienberger (University of Salzburg), Ana Lopez (University of Oxford), Colin McQuistan (Practical Action, Rugby), Jaroslav Mysiak (FEEM, Venice), Ilan Noy (University of Wellington), Joeri Roegelj (IIASA), Olivia Serdeczny (Climate Analytics, Berlin), Swenja Surminski (LSE, London), Koko Warner (UNU-EHS, Bonn)

References

Bouwer LM (2013). Projections of future extreme weather losses under changes in climate and exposure. RiskAnalysis 33(5):915–930

Herring, S.C., Hoerling, M.P., Peterson, T.C., Stott P.A. (eds) (2014). Explaining extreme events of 2013 from a climate perspective. Special Supplement to the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 95(9)

James, R., Otto, F., Parker, H., Boyd, E., Cornforth, R. Mitchell, D. and M. Allen (2014). Characterizing loss and damage from climate change. Nature Climate Change 4: 938-39

Mechler, R. Bouwer, L., Linnerooth-Bayer, J., Hochrainer-Stigler, S., Aerts, J., Surminski, S. (2014). Managing unnatural disaster risk from climate extremes. Nature Climate Change 4: 235-237

Peterson, T.C., Hoerling, M.P., Stott, P.A., Herring, S.C. (2013). Explaining Extreme Events of 2012 from a Climate Perspective. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 94: S1–S74. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-13-00085.1

Trenberth, K.E., Fasullo, J.T., Shepherd, T.G. (2015). Attribution of climate extreme events. Nature Climate Change 5: 725–730. doi:10.1038/nclimate2657

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 11, 2015 | Demography

IIASA demographer Erich Striessnig talks about new research linking population change with climate change scenarios.

What does your research say about population and climate?

In our recent review article published in the journal Population Studies, we give a summary of much of the work that has been carried out over the past few years both at IIASA and at the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (IIASA, VID/ÖAW; WU) on the contribution of changes in population size and structures to greenhouse gas emissions, as well as societies’ capacity to adapt to climate change. Similar to Mia Landauer in last week’s blog entry, we emphasize the importance of addressing challenges to mitigation and adaptation jointly.

What’s new or unexpected in this study?

The main novelty behind our approach is the explicit inclusion of the full population detail by age, sex, and educational attainment in assessments of societies’ future adaptive and mitigation potential. This is exemplified in the context of IPCC-related climate change modelling which until recently has included only very limited information on the future of population. The new Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs), which were developed with a huge contribution by IIASA, are an important step to overcoming this situation and to make models of both future greenhouse gas emissions, as well as vulnerability and adaptive capacity with respect to climate change far more realistic.

Population characteristics – not just numbers – make a major impact on greenhouse gas emissions as well as people’s ability to adapt to a changing climate. ©Chris Ford via Flickr

Why is it important to consider the composition of population in regards to future climate change issues?

When thinking about the challenges of the future, it is important also to think about the capabilities that future societies will have to face them. I don’t mean that we should simply lean back and wait for science-fictional future technologies to solve all the problems of humanity, but a look at the changing future composition of populations around the world gives reason for optimism that future societies will be better at preparing, coping, and dealing with the consequences of yet unavoidable climate change than we are today.

What are the links between education and climate change?

Particularly in the developing world, education leads to reduced poverty. But economic growth and the resulting greater affluence, and consumption, also increases global CO2 emissions. So on a first look, education appears to worsen climate change. This has made some environmental activists skeptical about the value of education in the context of mitigation. But to avoid playing poverty eradication and well-being against climate change mitigation, it is necessary to look at behavioral differences at given levels of income. In fact, better education has been shown to be related to more eco-friendly consumption behavior, especially when it comes to home energy use and transportation, two of the main drivers of climate change. In addition to that, education has also been a major driver of technological advancements in the transition to cleaner energy sources.

Research shows that people’s education levels also play a role in how adaptable they are to potential climate-related impacts such as storms and floods. ©Aldrich Lim via Flickr

How do the new SSPs bring demography into the study of climate change?

Population growth is undoubtedly one of the main drivers of greenhouse gas emissions and thus climate change. What’s far less acknowledged is the importance of differential climate impact depending on demographic characteristics. Groundbreaking work by researchers from IIASA and the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) featured in the article has shown that people have different footprints when they are young than when they are old and that household consumption differs between rural and urban dwellers. Providing different scenarios for the future composition of populations by age, sex, and educational attainment, the new SSPs for the first time allow researchers from different fields to study the dynamics between population and climate change within a common reference frame.

References

Lutz W, Striessnig E (2015) Demographic aspects of climate change mitigation and adaptation. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography, 69(S1):S69-S76 (April 2015). doi: 10.1080/00324728.2014.969929

O’Neill, Brian C., Michael Dalton, Regina Fuchs, Leiwen Jiang, Shonali Pachauri, and Katarina Zigova. “Global Demographic Trends and Future Carbon Emissions.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 (October 2010): 17521–26. doi:10.1073/pnas.1004581107.

Note: This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Apr 30, 2015 | Energy & Climate

In a new study in the journal Climatic Change, IIASA Guest Research Scholar Mia Landauer explores the interrelationships between policies dealing with climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Why did you decide to do this study?

Adaptation and mitigation have been traditionally handled as two separate policies to combat climate change. We wanted to explore whether adaptation and mitigation can or should be considered together, because the implementation of the two policies takes place at different scales and the goals of the two climate policies are often considered distant from each other. We approached this question with a systematic literature review, because although such reviews are common in other research fields such as health sciences, there are only a few examples in social and environmental sciences. Ours was the first systematic analysis on how the interrelationships have been studied across different research fields and how these studies have conceptualized the issue.

Cities are at the forefront of climate policy making and climate impacts. The United Nation Headquarters complex in New York turns out their lights in observance of “Earth Hour,” in 2015. Credit: John Gillespie via Flickr

What were the major findings of your study? What was new or unique?

We found that cities in particular should consider adaptation and mitigation together, because cities are in the forefront of climate policy making and urban actors have to negotiate trade-offs between the two climate policies across multiple scales. We found the highest number of publications on interrelationships between adaptation and mitigation from the field of urban studies.

Our systematic review provides knowledge on how synergies can be identified and conflicts avoided across different urban sectors and scales which is valuable for urban decision makers and planners when they have to consider climate policy making and planning practices.

Why are cities important when researching climate change adaptation and mitigation?

Our systematic review reveals that there is an increasing interest to study the interrelationships especially in cities, which face challenges of global change both in developing and developed countries. Especially under limited resources, integrated adaptation and mitigation strategies can provide a possibility to increase efficiency of cities’ responses to climate change.

A green wall in Paris shows just one example of building innovations to help mitigate climate change. Credit: Mia Landauer 2013

What are the major conflicts and synergies you identified?

At the organizational scale, the trade-offs and conflicts we found between adaptation and mitigation showed up especially in urban policy and administrative processes, and allocation of resources. In practice, conflicts appear especially when there are competing land uses such as between public and private land. We also identified a number of synergies, which are indications of positive interrelationships. In practice, synergies can be found particularly in the building, infrastructure and energy sectors, with examples ranging from passive building design to urban greening and alternative energy options. In order to enhance synergies, changes in regulations and legislation, policy and planning innovations, raising awareness and cooperation between different actors and sectors should be considered.

How can this information be applied for policy making?

Integration of adaptation and mitigation can reduce vulnerability to climate change and help to implement climate policy and planning in a resource-efficient manner. Our analysis identified many opportunities that can be gained from integration of adaptation and mitigation. Especially in cities we find that it can be beneficial for decision makers and planners to consider adaptation and mitigation policies together, in order to avoid conflicts in planning practices and negotiate difficult trade-offs.

Reference

Landauer M, Juhola S, Soederholm M (2015) Inter-relationships between adaptation and mitigation: a systematic literature review. Climatic Change, Article in press (Published online 8 April 2015) http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10584-015-1395-1

Note: This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.