Aug 31, 2018 | Climate Change, Science and Policy, Women in Science, Young Scientists

by Melina Filzinger, IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Yuping Bai is a participant of the IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) and a first year PhD candidate at the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research. She is working with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the leading international body for the assessment of climate change, as a chapter scientist for their Special Report on Climate Change and Land. I recently had the chance to talk to her about her engagement as a chapter scientist.

© Yuping Bai

What is the aim of the IPCC special report on climate change and land?

Compared to the IPCC comprehensive assessment reports, this special report really focuses in depth on the linkages and inter-relationship between climate change, land use, and food security. It aims to propose sustainable land-based solutions towards climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts. We all know that climate change is an important issue and the connections between climate change and land use change are extremely complex. The report will include many different topics like land degradation, desertification, greenhouse gas fluxes and food security. Understanding the links between these diverse issues is particularly important for informing decision making by governments, as well as private sectors, to address challenges in land use change and governance.

What is a chapter scientist?

Chapter scientists are early-career researchers that support the development process of the individual report chapters. IPCC asked for volunteers who are required to dedicate at least one-third full time equivalent over a 2.5-year period while working from their home institutions. The chapter scientists were chosen based on expertise, motivation, time availability, and experience in working in a multi-cultural context. There are ten chapter scientists in total working on the report, one or two for each chapter.

How do you contribute to the report?

I am assigned to Chapter 1, which provides the framing and context for the report. Part of my job has been organizational tasks, for example managing our referencing system, scheduling online meetings, tracking down key literature, assisting in the design and development of figures and tables, and assisting in compiling, revising, and organizing chapter contributions. On the other hand, I have also been involved in developing the overall concept of our chapter and can voice my ideas and express my views. Chapter 1 raises the key issues related to land use and sustainable land management for climate adaptation and climate resilience, and provides the concepts and definitions needed to understand the rest of the report.

In fact, many of these topics are closely related to my PhD research and my YSSP project. The YSSP experience significantly broadened my knowledge on climate change and land related topics, and at the same time deepened my understanding of the cross-scale complexity of the issues. After three months, I feel that I’m much better equipped to contribute to the future work for the chapter.

Why did you decide to volunteer so much of your time?

As a chapter scientist I have the chance to participate in discussions on some of the most pressing and important issues in the world. I also have the unique possibility to work with some of the world leading scientists in their respective fields. Therefore, I think it’s an important opportunity to make contacts and to gain insight into the work of the IPCC.

What has your experience been so far?

I’m the youngest one of the chapter scientists, so I felt a bit overwhelmed at first, particularly as I was suddenly rubbing shoulders with some of the brightest, most established academics and researchers on the planet. In this first half year, I attended the second lead author meeting and have been involved in the first draft of the report. During busy periods leading up to key deadlines, such as the submission of the drafts, my hours peaked, and the pressure built. But don’t let this frighten you. It is possible to learn on the job! It helped that everyone made me feel so welcome and valued. I have definitely learned a lot. My research is very specialized, and my work with the IPCC has helped me gain a broader view on climate change and the problems that are connected to it.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 27, 2018 | Data and Methods, Ecosystems, Postdoc

by Melina Filzinger, IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Ecosystems worldwide are changed by the influence of humans, often leading to the extinction of species, for example due to climate change or loss of natural habitat. But it doesn’t stop there: as the different species in an ecosystem feed on each other and are thereby interconnected, the loss of one species might lead to the extinction of others, which can even destabilize the whole system. “In nature, everything is connected in a complex way, so at first glance you cannot be sure what will happen if one species disappears from an ecosystem,” says IIASA postdoc Mateusz Iskrzyński.

This is why the IIASA Evolution and Ecology (EEP) and Advanced Systems Analysis (ASA) programs are employing food-web modeling to find out which properties make ecosystems particularly vulnerable to species extinction. Food webs are stylized networks that represent the feeding relationships in an ecosystem. Their nodes are given by species or groups of species, and their links indicate how biomass cycles through the system by means of eating and being eaten. “This type of network analysis has a surprising power to uncover general patterns in complex relationships,” explains Iskrzyński.

Every one of these food webs is the result of years of intense research that involves both data collection to assess the abundance of species in an area, and reconstructing the links of the network from existing knowledge about the diets of different species. The largest of the currently available webs contain about 100 nodes and 1,000 weighted links. Here, “weighted” means that each link is characterized by the biomass flow between the nodes it connects.

Usually, food webs are published and considered individually, but recently efforts have been stepped up to collect them and analyze them together. Now, the ASA and EEP programs have collected 220 food webs from all over the world in the largest database assembled so far. This involved unifying the parametrization of the data and reconstructing missing links.

The researchers use this database to find out how different ecosystems react to the ongoing human-made species loss, and which ones are most at risk. This is done by removing a single node from a food web, which corresponds to the extinction of one group of species, and modeling how the populations of the remaining species change as a result. The main question is how these changes in the food web depend on its structural properties, like its size and the degree of connectedness between the nodes.

From the preliminary results obtained so far, it seems that small and highly connected food webs are particularly vulnerable to the indirect effects of species extinction. This means that in these webs the extinction of one species is especially likely to lead to large disruptive change affecting many other organisms. “Understanding the factors that cause such high vulnerability is crucial for the sustainable management and conservation of ecosystems,” says Iskrzyński. He hopes that this research will encourage more, and more precise, empirical ecosystems studies, as reliable data is still missing from many places in the world.

As a next step, the scientists in the two programs are planning to understand which factors determine the impact that the disappearance of a particular group of organisms has. They are going to make the software they use for their simulations publicly available, together with the database they developed.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 7, 2018 | Data and Methods, Risk and resilience, Women in Science, Young Scientists

by Melina Filzinger, IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Having just finished tenth grade, Lillian Petersen from New Mexico, USA is currently spending the summer at IIASA, working with researchers from both the Ecosystems Services and Management (ESM), and Risk and Resilience (RISK) programs on developing risk models for all African countries.

At a talk Petersen gave at the Los Alamos Nature Center/Pajarito Environmental Education Center, her method for predicting food shortages in Africa from satellite images caught the attention of Molly Jahn from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Jahn, who is collaborating with the ESM and RISK programs at IIASA, was so impressed with Petersen’s work that she added her to her research group and connected her to IIASA researchers for a joint project.

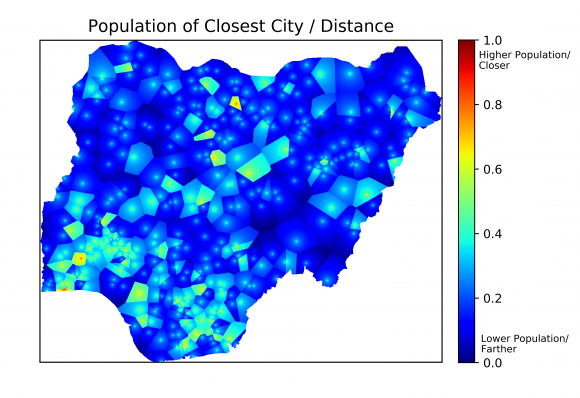

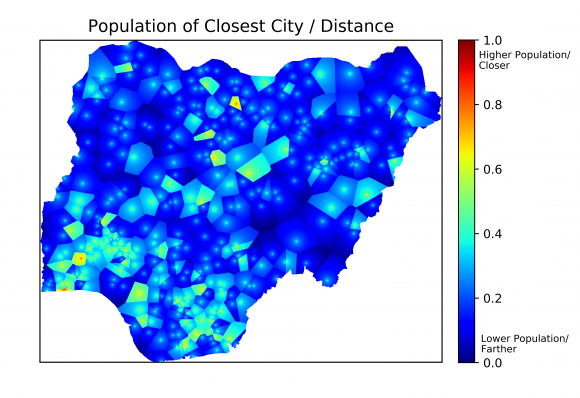

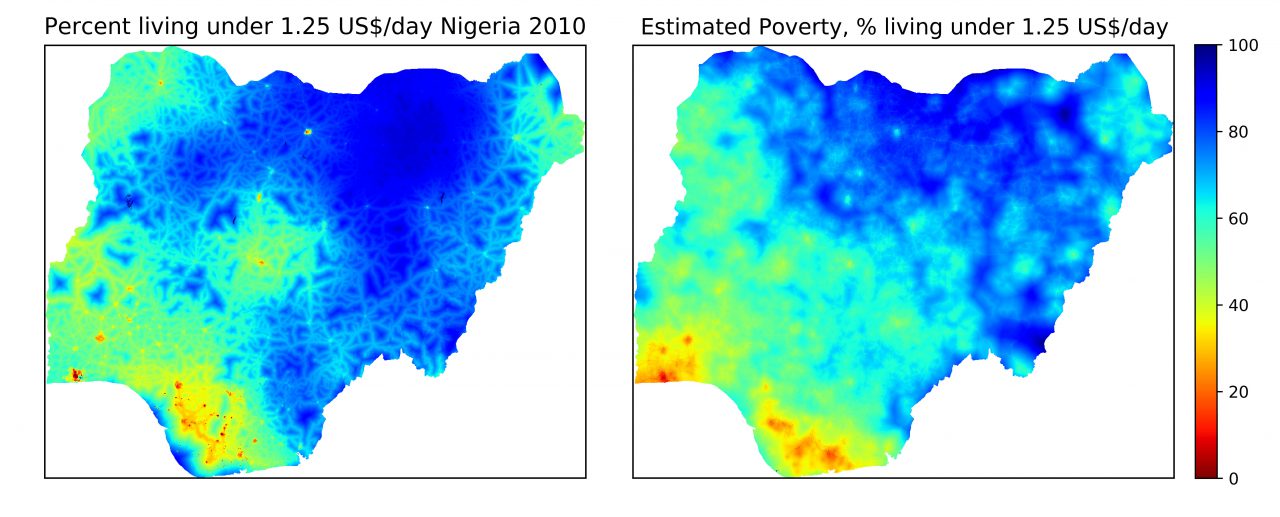

One of the indicators used to estimate poverty in Nigeria. © Lillian Petersen | IIASA

Knowing which areas are at risk for disasters like conflict, disease outbreak, or famine is often an important first step for preventing their occurrence. In developed countries, there is already a lot of work being done to estimate these risks. In developing countries, however, a lack of data often hinders risk modeling, even though these countries are often most at risk for disasters.

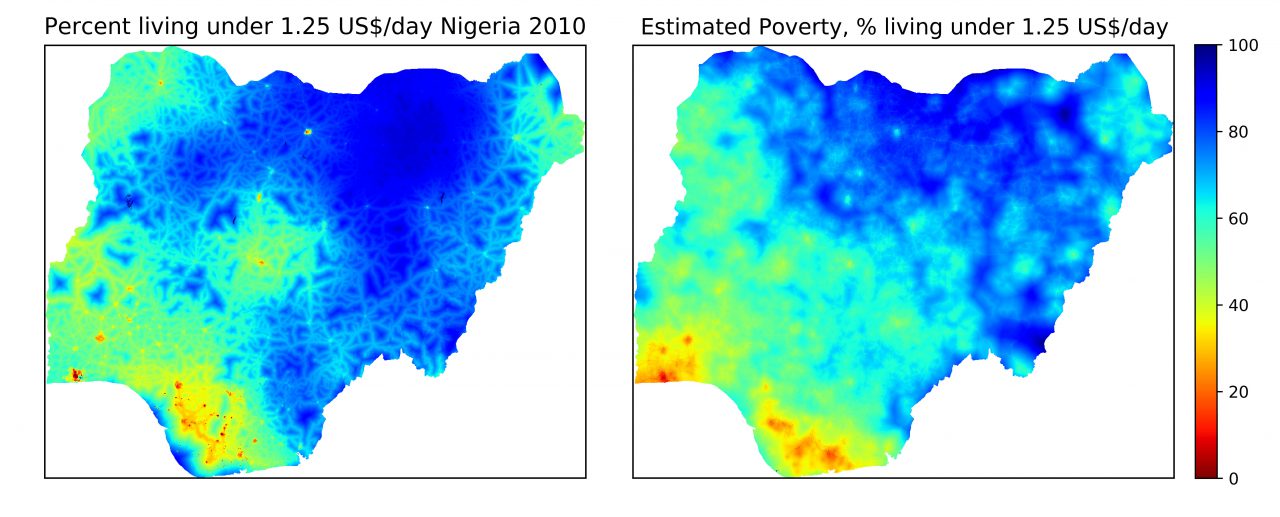

Many humanitarian crises, like famine, are closely connected to poverty. However, high resolution poverty estimates are only available for a few African countries. This is why Petersen and her colleagues are developing methods to obtain those poverty estimates for all of Africa using freely available data, like maps showing major roads and cities, as well as high-resolution satellite images. Information about poverty in a certain region can be extracted from this data by considering several indicators. For example, areas that are close to major roads or cities, or those that have a large amount of lighting at night, meaning that electricity is available, are usually less poor than those without these features. The researchers are also analyzing the trading potential with neighboring countries, the land cover type, and distance to major shipping routes, such as waterways.

As no single one of these indicators can perfectly predict poverty, the scientists combine them. They “train” their model using the countries for which poverty data exists: A comparison of the model’s output and the real data helps to reveal which combination of indicators gives a reliable estimate of poverty. Following this, they plan to apply that knowledge in order to accurately predict poverty with high spatial resolution over the entire African continent.

Poverty data for Nigeria in 2010 (left) and poverty estimates based on five different indicators (right). © Lillian Petersen | IIASA

Once these estimates exist, Petersen and her colleagues will apply risk models to find out which areas are particularly vulnerable to disease outbreaks, famine, and conflicts. “I hope that this research will inform policymakers about which populations are most at risk for humanitarian crises, so that they can target these populations systematically in aid programs,” says Petersen, adding that preventing a disaster is generally cheaper than dealing with its aftermath.

The skills Petersen is using for her research are largely self-taught. After learning computer programming with the help of a book when she was in fifth grade, Petersen conducted her first research project on the effect of El Nino on the winter weather in the US when she was in seventh grade. “It was a small project, but I was pretty excited to obtain scientific results from raw data,” she says. After this first success she has been building up her skills every year, by competing at science fairs across the US with her research projects.

Her internship at IIASA gives Petersen access to the resources she needs to take her research to the next level. “Getting feedback from some of the top scientists in the field here at IIASA is definitely improving my work,’’ she says. Petersen is hoping to publish a paper about her project next year, and wants to major in applied mathematics after she finishes high school.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 31, 2018 | Data and Methods, Young Scientists

by Melina Filzinger, IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Strategic board games are staple entertainment for families all over the world, but what many do not know is that games can also be a valuable research tool. As her project for the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP), Sara Turner is piloting an experiment that uses a game called the Forest Game, developed by IIASA and the Centre for Systems Solutions, to find out how policy decisions are made and how they change over time. “Games let you abstract from the specifics of a real-world case, but are more human-centric than, for example, computer simulations,” says Turner.

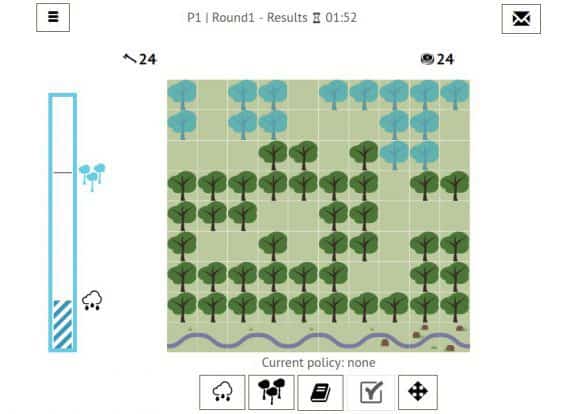

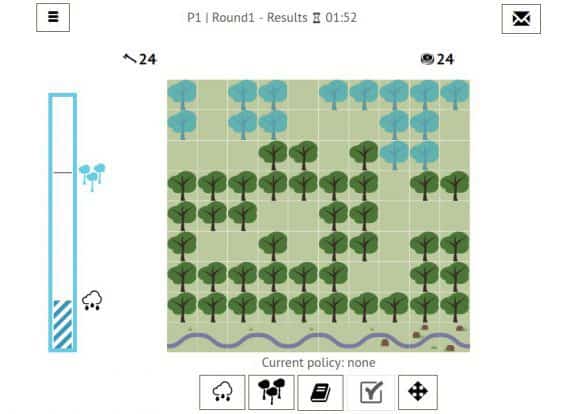

Interface of the Forest Game, © IIASA

In the Forest Game, a group of five to ten players is asked to make decisions about the management of a forest together. Harvesting trees yields returns for the players, while harvesting too many of them might destroy the forest or increase the risk of flooding. There are some uncertainties in the game – for example, the players do not know exactly how resilient the forest is. The goal of the research project is to run multiple iterations of the game with different players and starting conditions, and trace how group discussions and the resulting decisions change over time. This helps to generate hypotheses about the ways in which individuals interact to generate policy outcomes. Each game takes about an hour to play.

Even though the Forest Game deals with forest management, this is only one example of a broader class of decision-making dilemma: when a resource is limited, and it is costly to prevent access, people will tend to over-exploit the resource. This in turn leads to a wide range of problems, from over-fishing to air pollution. Although games cannot capture the complexity of real situations, they can still help us understand the core dynamics of the problem and develop ideas and strategies that are relevant to solving it. “The game is not designed to be directly applicable to real life, but it helps to come up with hypotheses that you can then compare to real-life cases,” explains Turner.

Questions about the sustainable management of resources have been studied for decades, but not a lot is known about the role values play in shaping group decision making and the stability of the implemented policies. To investigate this, each participant is asked to fill out a short ten-minute survey assessing their core values and beliefs, after which they are put into a group with people who either have a very similar or very different worldview from them. “It is really interesting to put a person in a decision-making context with other people and get some insight into how they work through that problem,” says Turner.

© Sara Turner

For example, if you are a person that strongly values equality, in the game you might be likely to argue in favor of a policy where all participants obtain the same amount of returns, regardless of the number of trees the individual player chooses to harvest. If many players in the group share your belief, that policy might be more likely to be implemented than in a very diverse group.

Another interesting question whenever you run a game for research purposes is, “Who are the right players?” Some games are targeted at real-world policymakers, but often games can also be educational for the broader public. ‘’People learn a lot during games, because of the way that information is processed and experienced,” says Turner. That is why many participants, although they might not see a connection between the game and their life at first, find themselves relying on the insights they gained while playing when faced with similar situations in the future.

In this case, the goal is to study group decision-making processes in general, so the details of who is playing are not particularly important. However, to obtain groups of players with heterogeneous worldviews, a high degree of diversity is preferable.

While the game has previously mainly been played by YSSP participants and students of the University of Vienna, Turner is currently trying to recruit a more diverse set of players from both within and outside of IIASA. “It would be ideal to have a pool of participants who come from a wide variety of educational and cultural backgrounds,” she says.

If you are interested in participating in the Forest Game, you can write Sara Turner an e-mail to turner@iiasa.ac.at.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 20, 2018 | Systems Analysis, Water, Young Scientists

By Melina Filzinger, IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Imagine you are heading home from work and are stuck in evening rush hour traffic. You see an opportunity to save time by cutting another driver off, but this will lead to a delay for other cars, possibly causing a traffic jam. Would you do it? Situations like these, where you can benefit from acting selfishly while causing the community as a whole to be worse off, are known as social dilemmas, and are at the heart of many areas of research in economics.

Tum Nhim (left) discusses water sharing with farmers and local authorities in rural Cambodia. © Tum Nhim

The social dilemma becomes particularly important when considering so-called common pool resources such as water reservoirs that are depleted when people use them. For instance, picture several farmers using water from the same river to irrigate their farmland. The river might carry enough water for all of them, but if there is no incentive for the upstream farmers to take the needs of the farmers living further downstream into consideration, they might use more than their share of the water, not leaving enough for the rest of the group. Situations like this are particularly relevant in developing countries, where small-scale farmers that manage the irrigation of their farmland themselves play a significant role in ensuring food security.

Growing up in southwestern Cambodia, YSSP participant Tum Nhim saw how the surrounding farmers shared water among themselves, and how important water was to their livelihoods. Not having enough water often meant that there were no crops for a whole year, and many farmers were forced to take on loans in order to feed their families. “Now that climate change is starting to affect Cambodia, and water scarcity is becoming an even bigger problem, it is more important than ever to investigate fair and efficient ways of sharing water,” explains Nhim.

As a water engineer, Nhim used to design and build water infrastructure. He however soon learned that not considering how human decision making affects the water supply will cause situations where the infrastructure provides enough water, but some farmers are still left high and dry. “I think that human behavior is the most important factor to consider when managing common pool resources,” he says.

To find possible solutions for distributing water in a way that yields an optimal outcome for the community, Nhim and his colleagues from the IIASA Advanced Systems Analysis Program use a bottom-up approach–they model the behavior of a number of individual farmers that interact according to certain rules. The researchers can then look at the collective outcome of these interactions after a certain time and ask questions like, “Will the farmers cooperate?” or, “Will some farmers be left without water?” In their model the researchers take into account both the water itself, a common pool resource, and the water infrastructure, which is not depleted by use.

Several mechanisms can be used to ensure the fair distribution of water. Some of them are formal; like laws and regulations, but it is often difficult to keep people from extracting water, because using a given water resource might be a long-standing cultural tradition or legal right. There are however also more informal mechanisms that can help. For example, individuals often prefer to be good citizens in order to ensure that they have a high social standing in their community that will bring them benefits.

This reputational mechanism is especially relevant in small communities with everyday contact between members. If someone takes too much water, or doesn’t invest in the common water infrastructure, they will gain a bad reputation, which will in turn limit their ability to get support from their neighbors later on.

The main question Nhim is investigating in his YSSP project is if this mechanism can spread across several villages that share a common water resource and irrigation infrastructure, and lead to an outcome where everyone cooperates. If this turns out to be true, the reputational mechanism could be a very inexpensive and natural solution for managing common goods across several communities.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.