An interdisciplinary research project explores glo-cal entanglements of power and nature in 18th century Vienna

By Verena Winiwarter, Guest Research Scholar, IIASA Risk and Resilience Program, and Professor, Centre for Environmental History, Alpen-Adria-Universitaet Klagenfurt.

Nowadays, rulers turn to primetime TV events to demonstrate their power, be it putting men on the moon, testing missiles, or building walls. When the kings of France, in particular Louis XIV and XV, built Versailles, they had the same goals: To claim their leading role in Europe and make their mastery of nature and their subjects visible for all.

In the 1700s, the Austro-Hungarian Empire had to pull off a comparable feat, in particular as Emperor Charles VI had a huge constitutional problem: His only surviving child, a smart and pretty daughter, was not entitled to the throne. Only men could be emperors of the Holy Roman Empire. So while eventually, an international agreement allowed young Maria Theresia to succeed him, her position was clearly weak and would become contested right after her father’s death.

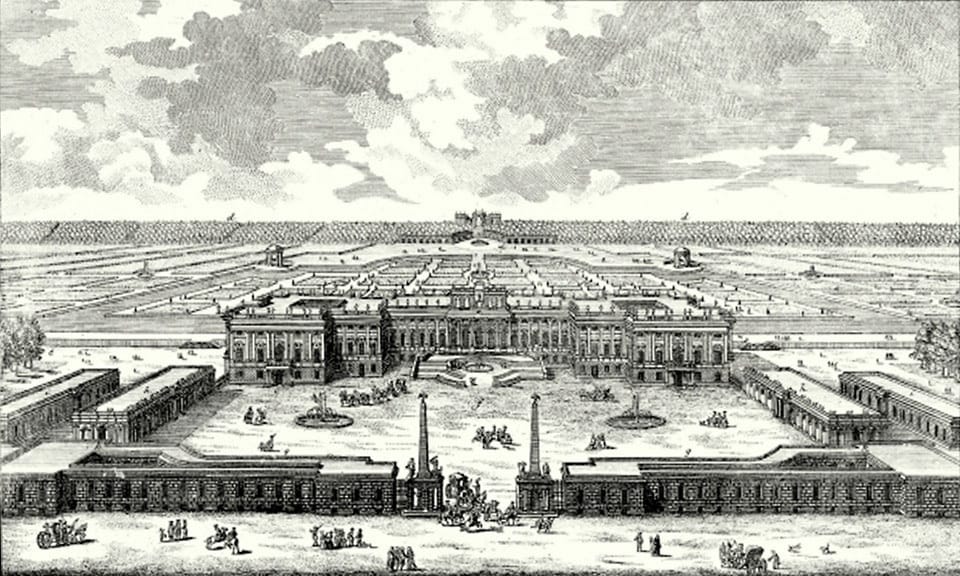

The construction of Vienna’ Schönbrunn Palace, and the taming of the river that flows by it, served as an international declaration of power by the Habsburgs and helped secure Maria Theresia’s position. Vienna, the Habsburg capital, already sported a summer palace in the game-rich riparian area to the west of the city center, close to a torrential, but rather small tributary of the Danube, the Wien River. Here, the leaders decided, a palace dwarfing Versailles should be built. One of the most famous architects of his time, J.B. Fischer von Erlach originally designed a grandiose structure that could never have been carried out. But it staked a claim and when seven years later, a more realistic plan was submitted, it became the actual blueprint of what today is one of Vienna’s most famous tourist sites.

Fischer v. Erlach’s second, more feasible design for Schönbrunn Palace (Public Domain | Wikimedia Commons)

While the kings of France built in a swamp and overcame a dearth of water by irrigation, the Habsburgs’ choice offered another opportunity to show just how absolute their rule was: the torrential Wien River had damaged the walls of the hunting preserve with its then much smaller palace several times. Putting the palace right there, into a dangerous spot, allowed the house of Habsburg to prove that their engineers were in control.

The flamboyant new palace was deliberately placed close to the Wien River, necessitating its local regulation. This had repercussions for those living up- and downstream, as flood regimes changed. Not all such change was beneficial, as constraining the river’s power meant that it found outlets elsewhere. In this case, European power struggles affected the course of a river, putting a strain on locals for the sake of global status.

In the 19th century, effects of global events and structures played out in favor of local health, when it came to building sewers along the by then heavily polluted Wien River. The 1815 eruption of the Tambora volcano in Indonesia led to unusually heavy rains during the otherwise dry season and the proliferation of cholera, which British colonial soldiers brought to Europe. A cholera epidemic hit Vienna in 1831/32, creating momentum to finally build a main sewer along Wien River. The first proposals for a sewer date back to 1792; they were renewed in 1822, but due to urban inertia, the sewer was not built. Thousands of deaths (18,000 in recurring outbreaks between 1831-1873) called for a response, and from 1831 onwards, collection canals were built.

A global constellation had first affected locals negatively, but with long-term positive outcomes of much cleaner water.

We uncovered these stories of the glo-cal repercussions of Wien River management during the FWF-funded project URBWATER (P 25796-G18) at Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt with the joint effort of an interdisciplinary team. We have shown in several publications how urban development was intimately tied to the bigger and smaller surface waters and to groundwater availability, telling a co-evolutionary environmental history.

The overall development of the dammed and straightened, then covered river can be seen in science-based videos by team member Severin Hohensinner for 1755. At 2:00 in the video, the virtual flight nears Schönbrunn on the right bank, with the regulation measures visible as red lines. A comparison between 1755 and 2010 is also available. Both videos start with an aerial view of downtown Vienna and then turn to the headwaters of the Wien, progressing towards the center with the flow.

More on the project, including links to publications and images are available at http://www.umweltgeschichte.uni-klu.ac.at/index,6536,URBWATER.html

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Thanks for this fascinating article about the geopolitics of the Wien Fluss. The path alongside it is one of my favorite bicycle trails that inspired me to write a short blog post called “The Life of the River” on my blog. https://aviott.org/2015/08/24/the-life-of-the-river/