Jun 12, 2017 | Citizen Science

By Linda See, IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program

Satellites have changed the way that we see the world. For more than 40 years, we have had regular images of the Earth’s surface, which have allowed us to monitor deforestation, visualize dramatic changes in urbanization, and comprehensively map the Earth’s surface. Without satellites, our understanding of the impacts that humans are having on the terrestrial ecosystem would be much diminished.

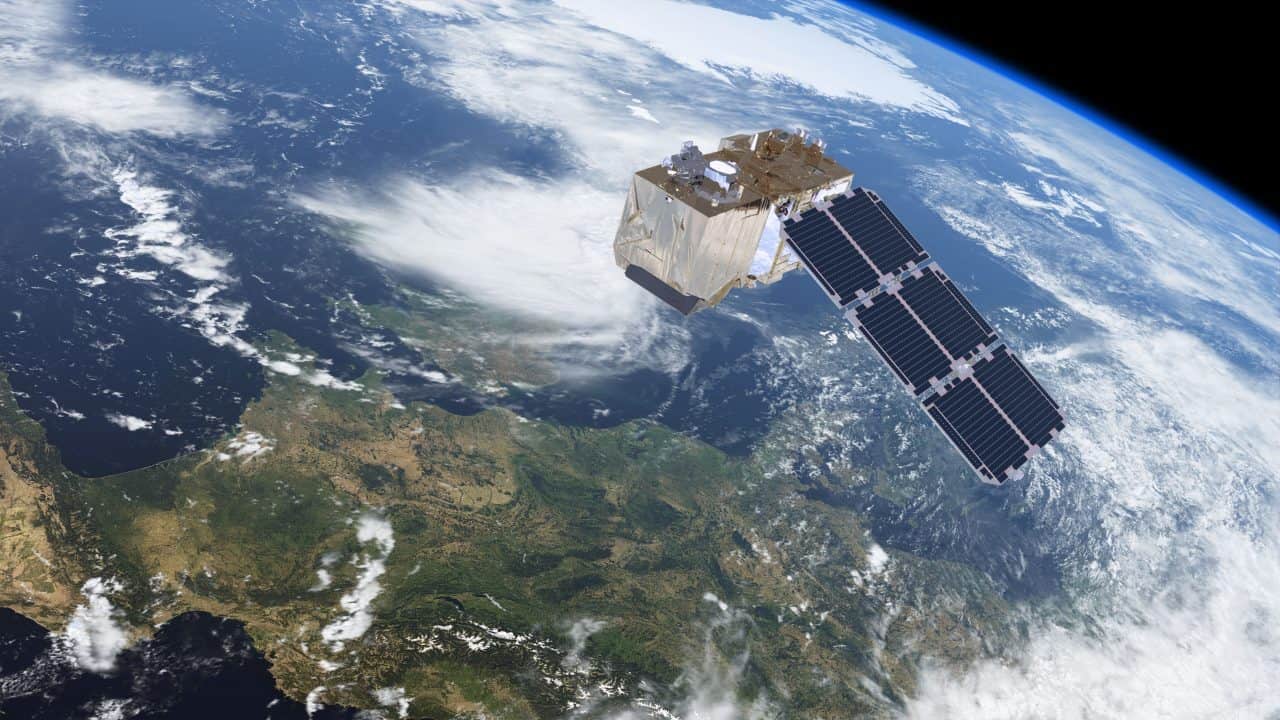

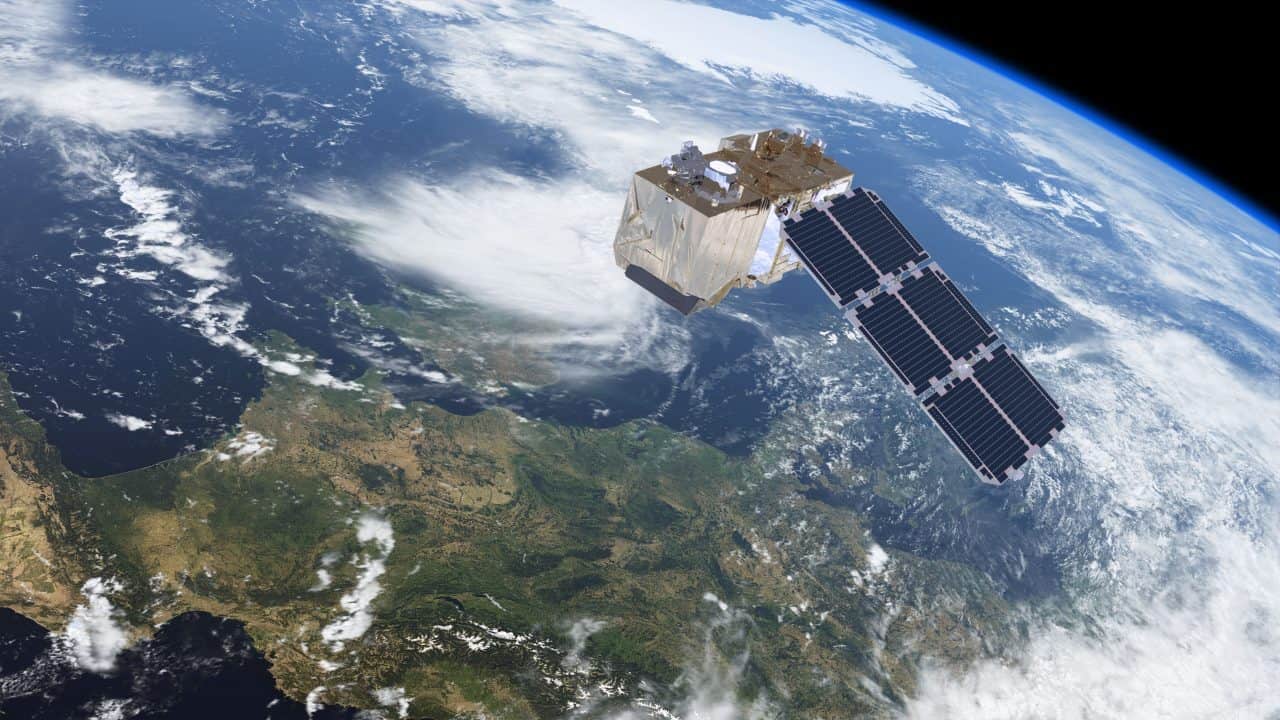

The Sentinel-2 satellite provides high-resolution land-cover data. © ESA/ATG medialab

Over the past decade, many more satellites have been launched, with improvements in how much detail we can see and the frequency at which locations are revisited. This means that we can monitor changes in the landscape more effectively, particularly in areas where optical imagery is used and cloud cover is frequent. Yet perhaps even more important than these technological innovations, one of the most pivotal changes in satellite remote sensing was when NASA opened up free access to Landsat imagery in 2008. As a result, there has been a rapid uptake in the use of the data, and researchers and organizations have produced many new global products based on these data, such as Matt Hansen’s forest cover maps, JRC’s water and global human settlement layers, and global land cover maps (FROM-GLC and GlobeLand30) produced by different groups in China.

Complementing Landsat, the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Sentinel-2 satellites provide even higher spatial and temporal resolution, and once fully operational, coverage of the Earth will be provided every five days. Like NASA, ESA has also made the data freely available. However, the volume of data is much higher, on the order of 1.6 terabytes per day. These data volumes, as well as the need to pre-process the imagery, can pose real problems to new users. Pre-processing can also lead to incredible duplication of effort if done independently by many different organizations around the world. For example, I attended a recent World Cover conference hosted by ESA, and there were many impressive presentations of new applications and products that use these openly available data streams. But most had one thing in common: they all downloaded and processed the imagery before it was used. For large map producers, control over the pre-processing of the imagery might be desirable, but this is a daunting task for novice users wanting to really exploit the data.

In order to remove these barriers, we need new ways of providing access to the data that don’t involve downloading and pre-processing every new data point. In some respects this could be similar to the way in which Google and Bing provide access to very high-resolution satellite imagery in a seamless way. But it’s not just about visualization, or Google and Bing would be sufficient for most user needs. Instead it’s about being able to use the underlying spectral information to create derived products on the fly. The Google Earth Engine might provide some of these capabilities, but the learning curve is pretty steep and some programming knowledge is required.

Instead, what we need is an even simpler system like that produced by Sinergise in Slovenia. In collaboration with Amazon Web Services, the Sentinel Hub provides access to all Sentinel-2 data in one place, with many different ways to view the imagery, including derived products such as vegetation status or on-the-fly creation of user-defined indices. Such a system opens up new possibilities for environmental monitoring without the need to have either remote sensing expertise, programming ability, or in-house processing power. An exemplary web application using Sentinel Hub services, the Sentinel Playground, allows users to browse the full global multi-spectral Sentinel-2 archive in matter of seconds.

This is why we have chosen Sentinel Hub to provide data for our LandSense Citizen Observatory, an initiative to harness remote sensing data for land cover monitoring by citizens. We will access a range of services from vegetation monitoring through to land cover change detection and place the power of remote sensing within the grasp of the crowd.

Without these types of innovations, exploitation of the huge volumes of satellite data from Sentinel-2, and other newly emerging sources of satellite data, will remain within the domain of a small group of experts, creating a barrier that restricts many potential applications of the data. Instead we must encourage developments like Sentinel Hub to ensure that satellite remote sensing becomes truly usable by the masses in ways that benefits everyone.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 25, 2016 | Science and Art

By Chantal Bilodeau, playwright

This could have been the title of my application to the first Citizen Artist Incubator (CAI) hosted at IIASA September 4-30, 2016. I am a Canadian playwright and research artist based outside of New York City, whose work deeply engages with climate change. For me, IIASA was the ultimate dating pool.

Playrwright Chantal Bilodeau is working on a series of plays about the impact of climate change on the eight countries of the Arctic. Photo courtesy Chantal Bilodeau

My belief in art/science romance was further reinforced when IIASA Director General and CEO Professor Dr. Pavel Kabat told us – thirteen artists from Europe, the Middle-East, Africa and America – during one of our sessions, “You have a big responsibility, my friends.” He was referring to the need for artists to engage with pressing global issues, and help change negative narratives into positive narratives of opportunity and social innovation. Big responsibility, indeed. And all the more reason for artists and scientists to become bedfellows.

I came to IIASA to do research for a play about human and animal migration, set in Alaska. The play is part of a long-term project titled The Arctic Cycle. A series of eight plays that look at the social and environmental changes taking place in the eight countries of the Arctic, The Arctic Cycle seeks to 1) bring attention to the changes happening in the Arctic and the impact those changes are having on local communities; 2) encourage international and multidisciplinary collaboration across Arctic countries, and; 3) translate scientific data into personal stories.

Sila was the first of the eight plays in the Arctic Cycle. it focuses on Canada. Credit: A.R. Sinclair Photography

I wanted to talk to scientists to get information for my play, but also to explore what might be possible. How can we join forces? How can my talent and skills and sphere of influence be combined with yours to create greater impact? I reached out to people in the Arctic Futures Initiative, the World Population program, and the Evolution and Ecology program. In addition to pointed questions about migration I asked questions like: “If there was one thing you would like people to understand about your field that I could communicate through my work, what would it be?” “Are there situations where having an artist’s perspective in addition to a scientist’s perspective would be useful?”

Everyone was extremely generous with their time and graciously answered my questions. I was pleased to find out there is genuine interest in investigating where art and science might intersect. The most obvious intersection, of course, is in “translating” scientific information into works of art that are then presented in traditional venues. But what about other intersections? Could artists facilitate conversations between scientists and stakeholders? Could a play (as I experienced once before) set the tone for an entire conference? What would be the value of having an artist embedded into a scientific program? Or a field trip?

Thanks to Gloria Benedikt, Merlijn Twaalfhoven, and their partners who invited me to participate in CAI, I came away from IIASA with concrete and up-to-date information for my play, and ideas for activities and programs that could bring art and science closer together around issues of climate change. I also left with a few email addresses and phone numbers. I am hoping this may be the beginning of a courtship that will lead to long and meaningful relationships.

Participants in the Citizen Artist Incubator 2016 ©Patrick Zadrobilek

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 4, 2016 | Climate Change, Food

By David Leclère, IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program

August was the warmest ever recorded globally, as was every single month since October 2015. It will not take long for these records to become the norm, and this will tremendously challenge food provision for everyone on the planet. Each additional Celsius degree in global mean temperature will reduce wheat yield by about 5%. While we struggle to take action for limiting global warming by the end of the century to 2°C above preindustrial levels, business as usual scenarios come closer to +5 °C.

However, we lack good and actionable knowledge on this perfect storm in the making. Despite the heat, world wheat production should hit a new record high in 2016, but EU production is expected to be 10% lower than last year. In France, this drop should be around 25-30% and one has to go back to 1983 to find yields equally low. Explanations indeed now point to weather as a large contributor. But underlying mechanisms were poorly anticipated by forecasts and are poorly addressed in climate change impacts research.

©Paul Townsend via Flickr

Second, many blind spots remain. For example, livestock has a tremendous share in the carbon footprint of agriculture, but also a high nutritional and cultural value. Yet, livestock were not even mentioned once in the summary for policymakers of the last IPCC report dedicated to impacts and adaptation. Heat stress reduces animal production, and increases greenhouse gas emissions per unit of product. In addition, a lower share of animal products in our diet could dramatically reduce pollution and food insecurity. However, we don’t understand well consumers’ preferences in that respect, and how they can be translated in actionable policies.

How can we generate adequate knowledge in time while climate is changing? To be able to forecast yields and prevent dramatic price swings like the 2008 food crisis? To avoid bad surprises due to large missing knowledge, like the livestock question?

In short: it will take far more research to answer these questions—and that means a major increase in funding.

I recently presented two studies by our team at a scientific conference in Germany, which was organized by a European network of agricultural research scientists (MACSUR). One was a literature review on how to estimate the consequences of heat stress on livestock at a global scale. The other one presented scenarios on future food security in Europe, generated in a way that delivers useful knowledge for stakeholders. The MACSUR network was funded as a knowledge hub to foster interactions between research institutes of European countries. In many countries, the funding covered travels and workshops, not new research. Of course, nowadays researchers have to compete for funding to do actual research.

So let’s play the game. The MACSUR network is now aiming at a ‘Future and Emerging Technologies Flagship’, the biggest type of EU funding: 1 billion Euros over 10 years for hundreds of researchers. Recent examples include the Human Brain Project, the Graphene Flagship, and the Quantum Technology Flagship. We are trying to get one on modeling food security under climate change.

© Sacha Drouart

Such a project could leapfrog our ability to deal with climate change, a major societal challenge Europe is confronted with (one of the two requirements for FET Flagship funding). The other requirement gave us a hard time at first sight: generating technological innovation, growth and jobs in Europe -but one just needs the right lens. First, agriculture already sustains about 44 million jobs in the EU and this will increase if we are serious about reducing the carbon content of our economy. Second, data now flows at an unprecedented speed (aka, big data). Think about the amount of data acquired with Pokemon Go, and imagine we would harness such concept for science through crowdsourcing and citizen-based science. With such data, agricultural forecasts would perform much better. Similarly, light drones and connected devices will likely open a new era for farm management. Third, we need models that translate big data into knowledge, and not only for the agricultural sector. Similarly, models can also be powerful tools to confront views and could trigger large social innovation.

To get this funding, we need support from a lot of people. The Graphene project claimed support from than 3500 actors, from citizens to industrial players in Europe. We have until end of November to reach 3500 votes, at least. If you think EU should give food security under climate change the same importance as improving the understanding of the human brain, or developing quantum computers, we need you. This will simply never happen without you! Please help us out with two simple actions:

- Go the proposal, and vote for/comment it (see instructions, please highlight the potential for concrete innovations)!

- Spread the word – share this post with your friends, your family, and your colleagues!

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 23, 2016 | Science and Art, Science and Policy

Gloria Benedikt was born to dance. She started at the age of three and since the age of 12 she has been training every day—applying the laws of physics to the body. But with a degree in government and an interest in current affairs, Benedikt now builds bridges between these fields to make a difference, as IIASA’s first science and art associate.

Conducted and edited by Anneke Brand, IIASA science communication intern 2016.

Gloria Benedikt © Daniel Dömölky Photography

When and how did you start to connect dance to broader societal questions?

The tipping point was when I was working in the library as an undergraduate student at Harvard University. I had to go to the theater for a performance, and thought to myself: I wish I could stay here, because there is more creativity involved in writing a paper than in going on stage executing the choreography of an abstract ballet. I realized that I had to get out of ballet company life and try to create work that establishes the missing link between ballet and the real world.

To follow my academic interest, I could write papers, but I had another language that I could use—dance—and I knew that there is a lot of power in this language. So I started choreographing papers that I wrote and rather than publishing them in journals, I performed them. The first work was called Growth, a duet illustrating how our actions on one side of the world impact the other side. As dancers we need to concentrate and listen to each other, take intelligent risks and not let go. If one of us lets go, we would both fall on our faces.

What motivated you make this career change?

We as contemporary artists have to redefine our roles. In recent decades we became very specialized, which is great, but we lost our connection to society. Now it’s time to bring art back into society, where it can create an impact. I am not a scientist. I don’t know exactly how the data is produced, but I can see the results, make sense of it and connect it to the things that I am specialized in.

How did you get involved with IIASA?

I first started interdisciplinary thinking with the economist Tomáš Sedláček who I met at the European Culture Forum 2013. A year later I had a public debate with Tomáš and the composer Merlijn Twaalfhoven in Vienna. Pavel Kabat, IIASA Director General and CEO, attended this and invited me to come to IIASA.

What have you done at IIASA so far?

For the first year at IIASA I created a variety of works to reach out to scientists and policymakers and with every work I went a step further. This year, for the first time I tried to integrate the two groups by actively involving scientists in the creation process. The result, COURAGE, an interdisciplinary performance debate will premiere at the European Forum Alpbach 2016. In September, I will co-direct a new project called Citizen Artist Incubator at IIASA, for performing artists who aim to apply artistic innovation to real-world problems.

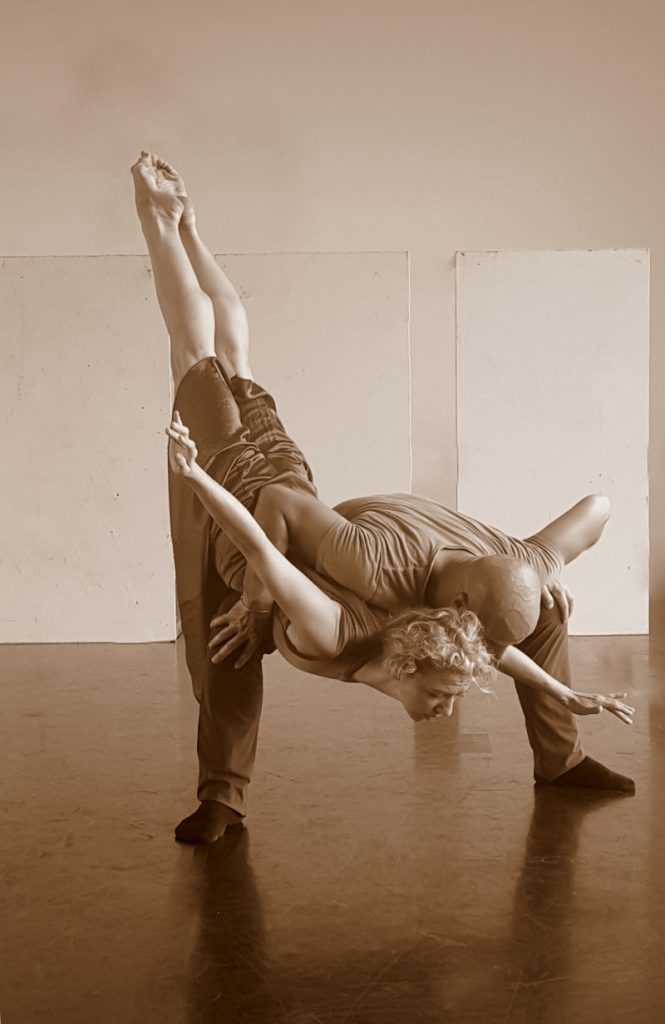

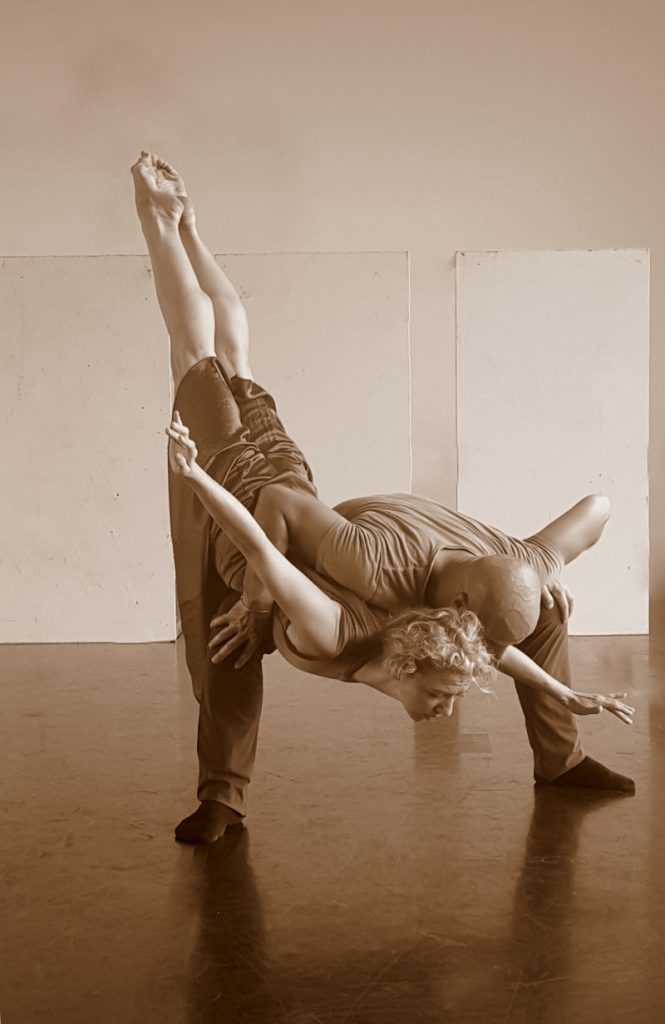

Gloria and Mimmo Miccolis performing Enlightenment 2.0 at the EU-JRC. The piece was specifically created for policymakers. It combined text, dance, and music, and reflected on art, science, climate change, migration and the role of Europe in it. © Ino Lucia

How do scientists react to your work?

The response to my performances at the European Forum Alpbach 2015 and the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (EU-JRC) was extremely positive. It was amazing to see how people reacted—some even in tears. Afterwards they said that they didn’t understand what I was trying to say for the past two days, but the moment that they saw the piece, they got it. Of course people are skeptical at first—if they were not, I will not be able to make a difference.

Gloria and Mimmo Miccolis rehearsing at Festspielhaus St. Pölten for COURAGE which will premiere at the European Forum Alpbach 2016.

What are you trying to achieve?

I’m trying to figure out how to connect the knowledge of art and science so that we can tackle the problems we face more efficiently. There are multiple dimensions to it. One is trying to figure out how we can communicate science better. Can we appeal to reason and emotion at the same time to win over hearts and minds?

As dancers we can physically illustrate scientific findings. For instance, in order to perform certain complicated movements, timing is extremely critical. The same goes for implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Are you planning on doing research of your own?

At the moment I am trying something, evaluating the results, and seeing what can be improved, so in a way that is a type of research. For instance, some preliminary results came from the creation of COURAGE. We found that if we as scientists and artists want to work together, both parties will have to compromise, operate beyond our comfort zones, trust each other, and above all keep our audience at heart. That is exactly what we expect humanity to do when tackling global challenges. We have to be team players. It’s like putting a performance on stage. Everyone has to work together.

More information about Gloria Benedikt:

Benedikt trained at the Vienna state Opera Ballet School, and has a Bachelor’s degree in Liberal Arts from Harvard University, where she also danced for the Jose Mateo Ballet Theater. Her latest works created at IIASA will be performed at the European Forum Alpbach 2016 as well as the International Conference on Sustainable Development in New York.

www.gloriabenedikt.com

Fulfilling the Enlightenment dream: Arts and science complementing each other

Note: This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jul 15, 2016 | Alumni, Climate, Climate Change, Young Scientists

César Terrer, participant in the IIASA 2016 Young Scientists Summer Program, and PhD student at Imperial College London, recently made a groundbreaking contribution to the way scientists think about climate change and the CO2 fertilization effect. In this interview he discusses his research, his first publication in Science, and his summer project at IIASA.

Conducted and edited by Anneke Brand, IIASA science communication intern 2016.

César Terrer ©Vilma Sandström

How did your scientific career evolve into climate change and ecosystem ecology?

I studied environmental science in Spain and then I went to Australia, where I started working on free-air CO2 enrichment, or FACE experiments. These are very fancy experiments where you fumigate a forest with CO2 to see if the trees grow faster. In 2014 I moved to London for my PhD project. There, instead of focusing on one single FACE experiment, I collected data from all of them. This allowed me to make general conclusions on a global scale rather than a single forest.

You recently published a paper in Science magazine. Could you summarize the main findings?

We found that we can predict how much CO2 plants transfer into growth through the CO2 fertilization effect, based on two variables—nitrogen availability and the type of mycorrhizal, or fungal, association that the plants have. The impact of the type of mycorrhizae has never been tested on a global scale—and we found that it is huge. I think it’s fascinating that such tiny organisms play such a big role at a global scale on something as important as the terrestrial capacity of CO2 uptake.

How did you come up with the idea? One random day in the shower?

Long story short, researchers used to think that plants will grow faster, and take up a lot of the CO2 we emit. They assumed this in most of their models as well. But plants need other elements to grow besides CO2. In particular, they need nitrogen. So scientists started to question whether the modeled predictions overestimated the CO2 fertilization effect, because the models did not consider nitrogen limitation. To find out, I analyzed all the FACE experiments and indeed I saw that in general plants were not able to grow faster under elevated CO2 and nitrogen limitation. However, in some cases plants were able to take advantage of elevated CO2 even under nitrogen limitation. I grouped together the experiments where plants could grow under nitrogen limitation and after a lot of reading I saw what they had in common: the type of fungi! It turned out that one type of mycorrhizae is really good at transferring large quantities of nitrogen to the plant and the other type is not.

How did that feel?

Awesome! When I saw the graph, I knew: this is going to be important. Of course, after this, my coauthors helped me to polish the story. Without them, the conclusions would not be as robust and clear.

So how does this process work? Where do the fungi get the nitrogen from?

Particular soils might have a lot of nitrogen, but the amount available for plants to absorb might be low. Also, plants have to compete with non-fungal microorganisms for nitrogen. So if there is not much there, the microorganisms take it all. It’s called immobilization. Instead of mineralizing nitrogen, they immobilize it so that plants cannot take it up, at least not in the short term. Some types of fungi are much more efficient in accessing nitrogen, and associated with roots they allow plants to overcome limitations.

Nitrogen mobilization abilities of different types of fungi. Growth of plants associated with fungi not beneficial for nitrogen uptake (illustrated as grass roots on the left) could be limited by low nitrogen availability in soil. Other plants have the advantage of increased nitrogen uptake due to their beneficial association with certain types of fungi (illustrated as yellow mushrooms connected to the roots of the tree on the right). ©Victor O. Leshyk.

What is the impact of your findings?

Plants currently take up 25-30% of the CO2 we emit, but the question is whether they will be able to continue to do so in the long term. Our findings bring good and bad news. On the one hand, the CO2 fertilization effect will not be limited entirely by nitrogen, because some of the plants will be able to overcome nitrogen limitation through their root fungi. But on the other hand, some plant species will not be able to overcome nitrogen limitation.

There was a big debate about this. One group of scientists believed that plants will continue to take up CO2 and the other group said that plants will be limited by nitrogen availability. These were two very contrasting hypotheses. We discovered that neither of the hypotheses was completely right, but both were partly true, depending on the type of fungi. Our results could bring closure to this debate. We can now make more accurate predictions about global warming.

What will you do at IIASA and how will you link it to your PhD?

I want to upscale and quantify how much carbon plants will take up in the future. If we are to predict the capacity of plants to absorb CO2, we need to quantify mycorrhizal distribution and nitrogen availability on a global scale. We are updating mycorrhizal distribution maps according to distribution of plant species. We know for instance that pines are associated with ectomycorrhizal fungi and always will be. To quantify nitrogen availability we use maps of different soil parameters that are available on a rough global scale.

© Adam Edwards | Dreamstime.com

About César Terrer

Prior to his PhD, Terrer studied at the University of Murcia in Spain and the University of Western Sydney in Australia.

Currently he is a member of the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial College London, UK. For this study he collaborated with researchers from the University of Antwerp, Northern Arizona University, Indiana University and Macquarie University.

In the IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program, Terrer works together with Oskar Franklin from the Ecosystem Services and Management Program and Christina Kaiser from the Evolution and Ecology Program.

Further reading

Note: This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.