Jan 13, 2021 | Communication, Egypt, Women in Science

By Shorouk Elkobros, IIASA Science Communications Fellow

Shorouk Elkobros shares her love for science communication and why she thinks it is pivotal for humanity.

Early 2020, I saw viral GIFs about social distancing and flattening the curve. I remember how useful and accessible it felt to have science communicated in such a fun and non-jargon way, especially during a global crisis.

In today’s post-truth world, misinformation campaigns travel fast. Hence, science communication’s role becomes pivotal to humanity. Anne Glover, the president of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, once said that “research not communicated is effectively research not done.”

What is science communication?

Science communication is the practice of educating and raising awareness of science-related topics. Science communicators, therefore, aspire to bridge the gap between science and the public and to inform decision makers.

But is it that easy?

You guessed it ̶ it is not. However, it is a challenge one would love to take on. Science communication is a constant game of problem solving.

Meme from the American sitcom television series Parks and Recreation | awwmemes.com

It is never about dumbing down information but rather about making it concise and clear. It requires a decent amount of practice, careful attention to language, and a deep understanding of the audience.

Enticing readers with clickbait information and sensationalized or misleading facts has almost pushed the reputation of science communication under the bus. Examples include the COVID-19 conspiracy theories that emerged amid the pandemic or climate change deniers’ campaigns that share fake scientific news to mislead the public.

Why I love science communication?

I come from a science background and a love for visual storytelling. After earning my master’s degree in climate sciences, I chose to become a science communicator because it brings me joy to make science relatable and fun for the public. For me, science communication is a great way to mainstream climate action.

In 2019, I worked closely with the CLICCS B1 team at the University of Hamburg, Germany, where I investigated how our imaginations of possible and plausible climate futures are socially and culturally constituted and embedded in broader visions of the future and belief systems. One thing I learned was that the mainstream media either tones down the climate crises or spreads alarming and apocalyptic messages. It was an eye-opening experience to investigate how climate change is communicated in the media and to recommend amends. However, I always wanted to practice what I preached. I was lucky to volunteer as an editor on the Climate Matters blog and as a video editor in conferences such as Tropentag 2019. The sense of satisfaction that I felt every time I worked on an article or a video made me realize that I want to pursue a career in science communication.

IIASA Science communication

In 2020 I was looking for opportunities to embark on a science communication learning journey to become a better science writer and a better storyteller. Having the chance to do a Science Communication Fellowship at IIASA was an experience that I hold near and dear to my heart. This program is targeted towards early career science communicators who want to sharpen their science communication skills. It was the perfect opportunity for me to transition from academia to the practical field.

Working closely with researchers to produce content on blogs, videos, and news-in-brief articles in the Options magazine 2020 winter edition gave me an excellent perspective on environmental, economic, technological, and social change all around the globe. Knowing that my work can provide the needed information to policymakers is so rewarding because I know it can make a change in the years to come. Interviewing early career researchers and IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program alumni, and listening to them discussing their work and future aspirations was awe-inspiring. I think my favorite project was producing a video on the biodiversity work done at IIASA because I was able to look beyond the research and highlight the researchers behind it. I figured one way people would relate to the science is if I put a human face to it.

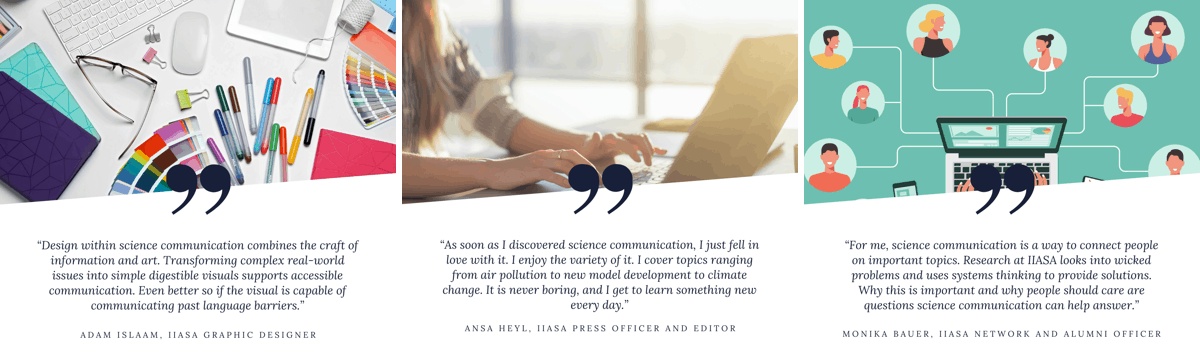

Working as part of the IIASA communications team has been a blast. For this blog, I asked my team members why they love science communication, and here are some of my favorite replies:

Communicating research addressing issues such as food and water security, biodiversity, or climate change can boost regenerative economies and decentralized renewable energy systems. It then becomes pivotal for humanity to give a voice to young people, grassroots movements, and people of color. Historically, researchers involved in outreach gave science communication its modern shape. Today, I think we live in a golden age of science communication. There are more thought-provoking science stories than ever before. Scientists blogging about science, science communicators using social media to promote recent publications, and storytellers creating science-oriented videos or designs, are all doing magnificent work, and I am lucky to count myself as one of them.

Communicating research addressing issues such as food and water security, biodiversity, or climate change can boost regenerative economies and decentralized renewable energy systems. It then becomes pivotal for humanity to give a voice to young people, grassroots movements, and people of color. Historically, researchers involved in outreach gave science communication its modern shape. Today, I think we live in a golden age of science communication. There are more thought-provoking science stories than ever before. Scientists blogging about science, science communicators using social media to promote recent publications, and storytellers creating science-oriented videos or designs, are all doing magnificent work, and I am lucky to count myself as one of them.

@ Lennart Wittstock | Pexels.com

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jun 29, 2018 | Communication, IIASA Network, United Kingdom, Women in Science

by Melina Filzinger, IIASA Science Communication Fellow

As a science communication fellow at IIASA, I had the opportunity to talk to Dame Anne Glover, who was recently made an IIASA distinguished visiting fellow. Originally a successful researcher in microbiology, she previously served as the first chief scientific adviser for Scotland, as well as the first chief scientific adviser to the president of the European Commission, and is now president of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

© Anne Glover

In your roles as scientific adviser you had to know about a broad range of relevant scientific topics. How do you keep informed about topics that lie outside your own area of research?

Of course no-one can be an expert in all the different areas of science. As a microbiologist, I am very specialized, but I am also a generalist when it comes to other areas of research. I keep up to date by reading articles about lots of different topics, from climate change to chemical toxicity or Alzheimer’s research, just because I am curious and interested.

However, if a minister or policymaker asked me to brief them on a particular topic, I would consult organizations with expertise in that area and ask them questions until I felt that I understood the topic. Then I would translate that scientific, often jargon-filled research into something that makes sense to a non-specialist. Part of the role as scientific adviser is not so much being an expert as being a translator.

Do you follow any science publications aimed at a broad audience? What are your favorites?

There is an organization called Sense about Science that publishes reports on issues that are being discussed among the public. They also have a fabulous service called Ask for evidence. Anyone can go onto their website and type a question, for example “Do female contraceptive pills end up feminizing fish in water streams?”, and they have a panel of experts that can comment on that, give you the evidence, and explain why this issue might or might not be a problem. It’s fantastic! I often use these answers as a starting point to find out about something.

I follow several other popular news outlets as well, for example New Scientist or the science and nature section of the BBC news app. I don’t expect absolute accuracy from those, I just expect to get a first impression of a research area. I also use Twitter as a source of information, because people often tweet about interesting science articles.

You are very active on Twitter. Has social media been useful to you, and how can it be used effectively?

I came to Twitter kicking and screaming when I joined the European Commission as chief scientific adviser to the president. I just thought that I had way too much to do to spend time on social media. It was Jan Marco Müller, a former colleague and now head of the directorate office at IIASA, who convinced me that Twitter could actually be a good way to tell people what I was doing, especially since transparency about my work is very important to me.

Have I found it useful? Enormously so! When I was at the commission I used it to see what really got people excited, either in a good way or in a bad way. When people were against a new technology, it helped me to understand their reasons. Tweeting is also an opportunity for me to help other people by highlighting interesting and useful events or initiatives. It can even be a little bit addictive.

How can science communicators and journalists reach a wide audience without oversimplifying scientific content?

The biggest nervousness I see among scientists is that of oversimplification. That is because, if you do oversimplify, you’re not going to upset your lay audience, but you will upset your scientific audience. I struggled with this for quite some time myself. Generally speaking, I would always favor simplification, of course not to the point of saying something that’s not true. I would however encourage scientists to be less afraid of simplification when speaking to a non-scientific audience. You will never be able to please everyone, you can only do your best to make an abstract subject accessible and interesting to people.

Do you have any tips for young scientists to make their work visible to the public?

In many cities there are science centers, museums, and other places where people get together, and there is nothing, other than their own modesty, to stop a young scientist from offering to talk about their work there. If it seems too daunting to do that kind of thing on your own, you could maybe do it with some of your colleagues. There are lots of opportunities out there for young scientists. Nobody is going to give those opportunities to you, but nobody is going to stop you either! You just have to take them!

If you do take them, think about what audience you are trying to reach beforehand, for example, if you want to talk to children or young adults. Then just be creative in how you present your research–try to build a story. Two good things will come out of it: one is that even if only 50 people show up, and only five of them are interested in what you are saying, you will have transformed the lives of those five people and made them excited about something. That is an achievement. The second thing is, that if you are doing things like that, and the young scientist next to you isn’t, it makes you different, and you have added value. You will also gain experience in communicating, which in turn will make the impact of your science much greater in the future. Everybody wins really, and it can be good fun as well.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Sep 12, 2017 | Science and Art, Systems Analysis

By Gerid Hager, IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program

©Gerid Hager | IIASA

In July, Miranda Lakerveld, a music drama artist and founder of the World Opera Lab, visited IIASA to run two storytelling workshops with young actors in civil society and youth policy, as well as with YSSP students and IIASA staff. Miranda first came to IIASA in September 2016 as part of the Citizen Artist Incubator.

After the workshops in July, Miranda and I sat down for a chat.

Gerid: Miranda, in the workshop you shared how you approach storytelling in your artistic practice. You said: “I’m looking for moments that feel true, I pick them up and weave them together into new stories.” Then, a participant exclaimed: “Stories are not true!” It seems a contradiction, but possibly this is the very nature of stories. They might not be true, giving accurate accounts of past events, but they carry truths in them, which we so often can’t capture otherwise. You’ve been working with myths for a long time: What value do you see in them today, as we’re trying to navigate between “alternative facts” and often incomprehensible scientific writing?

Miranda: Yes, this was a short reflection on the methodology I have developed and applied in many different contexts over the last eight years. It uses comparative mythology as a starting point. The aim of the method is to create a meaningful creative exchange that can involve people from all walks of life. Myths are examined from the perspectives of different cultures, and through this intercultural lens, we find symbols and archetypes that resonate as ‘true’ across cultures.

The ‘post-truth’ era made us extra aware of the divides between communities and I believe such an embodied practice of mythology can be an inspiring place for people to meet. I think the renunciation of facts and scientific insight is a symptom of people feeling left out and angry. Using myths and stories can be one way to bring people together and find common truths.

This workshop was part of the Systems Thinking for Transformation project and we wanted to search for “systems stories” in ancient narratives. We arrived at a very personal story of endurance and adaptation, pondered the power of great nature and cyclical behavior on a very large scale, and discussed economic justice and its relation to sustainable development. How does one story from Greek mythology – the Hymn to Demeter – lead to such diverse considerations?

The development of myths and folk stories has very specific characteristics, which I like to compare to ecosystems. Symbols and characters create organisms in constant interaction with their environments. Through time, myths change, in fertile circumstances the stories flourish, and layers of meaning are added.

Participants relate the Greek myth to myths from their own cultural backgrounds, and then to their personal histories. Interestingly, in the encounter between the myth and a group, some deeply felt preoccupations spring up from under the surface. I am still not sure how this happens. It probably has to do with a combination of embodiment of the characters, the richness of the archetypes, and the mise en scène, which represents the people inside the larger system.

Majnun & Leyla- World Opera Lab 2016- photo by Fouad Lakbir

One integral part of systems thinking is to be able to consider and explore multiple perspectives on a problem or situation. How does the embodiment exercise come in to this?

Slipping into different characters from the story is an essential part of the process. It unlocks the creative imagination and is related to action in society. The Greek root-word for drama is “dran”, which means “to act”. Through embodiment we can take the position of another character or force in the system. The performing arts make this possible: we can take on different roles, understand new parts, and at the same time experience the whole system from a new perspective.

There are other examples of how art and science meet through storytelling. A researcher at Berkeley University teamed up with story artists from PIXAR to help researchers create better stories about their research. What interests you in working with scientists and what is the role of storytelling?

I think the collaboration between art and science could go far beyond creating stories about research. We see very different approaches of creating and transmitting knowledge. So we have to deal with this tension but an inclusive society also means we should value these differences. The academic world has created an intricate system of validating knowledge leading to very specialized fields of research. Artists work on larger ideas, but the output cannot necessarily be validated. We are trying to grasp truths about the same river, but we work from opposite river banks. I think we can build bridges and increase our ability for insight and action by telling stories together.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 23, 2017 | Communication

Michaela Maier is a professor of applied communication psychology at the Institute of Communication and Media Psychology, University of Koblenz-Landau, Germany. Her work spans many forms of communication from crisis to election coverage to participatory decision making. She talks to IIASA Science Writer and Editor Daisy Brickhill.

Why is it important to communicate scientific uncertainty?

For us as researchers scientific uncertainty is something very natural that we consider all the time. We assess things like quality of samples used or numbers of replications, we justify and evaluate our research by taking into account a wider body of literature that may or may not show similar results. However, the degree of scientific uncertainty is not something that the public is so aware of. It is quite likely that it has not have been part of their education to learn the methods of evaluating the degree of (un)certainty of scientific evidence.

© Michaela Maier

Despite that, the public will almost definitely experience situations where they will have to evaluate uncertainty. As patients they might have to give their consent to a new medical treatment; as consumers they might need to decide whether to buy products that include, say, nanotechnology or genetically modified plants. Also as citizens—scientific evidence is relevant to many political decisions and as a voter you have to decide about these policies on election day. There are many situations where laypeople have to make judgements based on scientific findings—and we should communicate about the (un)certainty of this evidence in terms that people can understand.

Communicating uncertainty and how it works in one field or for one result can also give people the tools to understand and make judgments about other cases. Uncertainty can cover many things – is the sample large enough to draw any firm conclusions? Is it really representative of the whole population you are interested in?

When communicating complex topics, scientists and journalists can be nervous that talking about uncertainty will undermine the public’s interest or trust in the research – you’ve done some research on this?

Yes, we used communication of uncertainty around the safety of nanotechnology as a case study. Before the experiment we asked the participants a series of questions on how interested they were in science in general, in getting engaged in citizen science projects for example, or how likely they were to go to science museums. We also asked about their trust in scientists using measures of their perceptions of scientists’ competence, willingness to protect the public from technological risks, and honesty. We then sent them media reports over the course of six weeks, and after that we gave them the surveys again.

We found that communicating uncertainty didn’t undermine interest in science. In fact, what we found was that for a certain group of people the interest in science increased when uncertainty was discussed in the media reports they read. These people have what is called a low ‘need for cognitive closure.’ This means they are more open-minded and have a willingness to consider new or inconsistent information.

And did it undermine trust?

Communicating uncertainty didn’t seem to make any difference to the level of trust in scientists in people with either high or low need for cognitive closure. Ultimately our work showed that you won’t harm interest in science or trust in scientists by communicating uncertainty. It might not make much difference to some people but for others they will become even more engaged. It’s a very positive message.

Outside of an experimental environment are there any ways of engaging people with these complex issues of uncertainty?

It’s certainly a challenge for us to find the right formats. Narrative structures are an important format to pursue I think. There is a lot of evidence that narrative structures—storytelling—help people deal with complex information and that they really learn from it. Narrative structures focus more on the characters, they have a storyline, they might give the audience a chance to identify with the researcher, for instance.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Mar 1, 2016 | Communication, Science and Policy

By IIASA Science Writer and Editor Daisy Brickhill.

“The thing about communicating science today is…people can always watch cat videos instead. And let’s face it, some of those clips are really funny.”

Marshall Shepherd, former president of the American Meteorological Society, smiles at the audience of this science communication seminar, aware of the frustrated sighs going on in the room, and in some cases the blank incredulity—people wouldn’t watch cat videos when they could be paying attention to my science, surely?

We are at the AAAS annual meeting, a vast conference with around 10,000 attendees from all walks of life, from toddlers to retired professors. The science presented here is truly diverse, and covers everything from radically successful new cancer treatments, to advances in artificial intelligence, to the IIASA session on how we can hope to achieve all 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Shepherd is speaking of his long career engaging with the public about his work on weather systems and climate change. “Get out of your ivory tower,” he urges all researchers. There are important issues at stake, and what if no one speaks for the scientific evidence?

However, communicating science effectively is not easy. Understanding something does not mean you are automatically good at explaining it. All through academic training researchers learn how to speak to people in their own field, who talk just like them. That’s important, they might be your next reviewer, after all. But it is only one, narrow form; engaging the public requires a high level of understanding, not just of the topic, but of the audience and communication itself.

“We have left behind the old idea of science communication where brains are empty vessels waiting to be filled,” says the next speaker, Barbara Klein Pope, executive director for communications for the National Academies. “They are a swamp, and we need to explore that swamp to communicate properly.” She describes research which tested the effects of different types of communication on people’s perceptions of social science, in terms of whether they felt it was worth funding, for instance (oh yes, I sense the academic ears pricking up now).

The mind is not an empty vessel waiting to be filled, it’s a swamp to be navigated.

The findings of this work led to a framework of three clear messages. First, use exemplars—a good example can do wonders—yes, your research might be relevant across reams of different cases but general, expansive terms are often vague and a simple example can bring clarity.

Second, the all-important yet surprisingly often neglected question, “Why do we care?” Bear in mind also that it’s not why you care, you’ve made a career out of this science, we know why you care, but why should your audience care.

Finally, use metaphors. Science is often very complex, and pretty much anyone outside your field will need something they can relate to—a familiar concept that they can use to begin to explore the new territory. In case you need more convincing, the use of metaphors was shown to have a significant effect on whether the public felt the work was worth funding.

At the end of that session I was struck by the parallels between this session and another I attended on science-policy interactions with speakers Vladimír Sucha, Daniel Sarewitz, and Peter Gluckman, all working at the forefront of science-policy.

Trust, built on good communication, is vital, the speakers all agreed. Interesting conclusions should not be buried at the end of a report, they should be at the start, just as they would be for the public, and any article or briefing should be kept as short and relevant as possible. Examples and metaphors play a role here too, and a good story with persuasive anecdotes can have much more impact than a dry report.

What not to do, Sucha reminds us, is send an email saying “Here are the links to 200 peer-reviewed papers on this, you’ll find it all there.” After all, policymakers can access cat videos just as easily as the rest of us.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Communicating research addressing issues such as food and water security, biodiversity, or climate change can boost regenerative economies and decentralized renewable energy systems. It then becomes pivotal for humanity to give a voice to young people, grassroots movements, and people of color. Historically, researchers involved in outreach gave science communication its modern shape. Today, I think we live in a golden age of science communication. There are more thought-provoking science stories than ever before. Scientists blogging about science, science communicators using social media to promote recent publications, and storytellers creating science-oriented videos or designs, are all doing magnificent work, and I am lucky to count myself as one of them.

Communicating research addressing issues such as food and water security, biodiversity, or climate change can boost regenerative economies and decentralized renewable energy systems. It then becomes pivotal for humanity to give a voice to young people, grassroots movements, and people of color. Historically, researchers involved in outreach gave science communication its modern shape. Today, I think we live in a golden age of science communication. There are more thought-provoking science stories than ever before. Scientists blogging about science, science communicators using social media to promote recent publications, and storytellers creating science-oriented videos or designs, are all doing magnificent work, and I am lucky to count myself as one of them.

You must be logged in to post a comment.