Mar 10, 2021 | Communication, IIASA Network, Science and Policy, Women in Science

By Marie Franquin, External Relations Officer in the IIASA Communications and External Relations Department

Marie Franquin writes about her first six months as part of the IIASA Communications and External Relations team.

This year has certainly been a great challenge for all of us, migrating our lives online and our offices to the living-room. Last summer, I finished my PhD and was ecstatic to have found a job at IIASA that encompassed day-to-day work on my favorite skills: international stakeholder engagement, policy interface, and interacting with researchers, including early career ones!

All of these aspects were covered in the newly launched 2021-2030 IIASA Strategy that was published in the winter. My challenge remained to know how I could best apply my science to policy and research skills to contribute to these goals. How do I help a systems analysis research community move towards more impact and increasing stakeholder engagement?

It quickly became obvious that my position in the external relations team required multitasking and honing a series of skills. The first and top skill that I have kept developing for the past six months was interacting with international stakeholders from all over the world, which included not only our National Member Organization (NMO) representatives and researchers from these countries, but also IIASA researchers and alumni. Working at IIASA I have already gained experience in developing relationships with stakeholders of the research community all over the world.

© Swietlana Malyszewa | Dreamstime.com

The IIASA stakeholder community also sheds new light on the value of the institute’s expertise in systems analysis for building international scientific partnerships, whether it be formal ones with my colleague Sergey Sizov and his science diplomacy expertise, or by facilitating research partnerships between our NMO countries and IIASA researchers.

With my colleague Monika Bauer, I am also learning about the future of stakeholder engagement and how to build virtual communities, like she’s doing with IIASA Connect:

“We are building the global systems analysis network on IIASA Connect. This tool allows colleagues, alumni, the institute’s regional communities, and collaborators to directly engage with each other and take advantage of the institute’s international and interdisciplinary network. It is something completely new for the organization,” she explains.

Our recent partnership with the Strategic Initiatives (SI) Program was aimed at better understanding the IIASA NMO countries and their individual research priorities for the next decades. I learned about local challenges and strengths and how countries have managed to move forward as a nation or by working hand in hand with their neighbors.

Coming from a research background, I am fascinated by the insights I am gaining working with IIASA communications colleagues on how to promote research and its impacts. I particularly enjoyed working with Ansa Heyl, helping IIASA experts build their policy brief submissions for the recent T20 Italy call for abstracts. As part of my skillset and center of interest, I aim to apply my science to policy skills here at IIASA to support the researchers and impacts of the amazing work done across the institute.

Having mostly worked with and for early career researchers for several years, I remain sensitive to their needs for career development opportunities. I am therefore excited to work with colleagues in the institute’s Capacity Development and Academic Training (CDAT) program to further define and support research excellence at IIASA, especially in the very promising next generation of systems scientists.

Few workplaces are so well connected and offer so many opportunities to develop such a broad range of skills as the IIASA Communications and External Relations team. As we are working towards fulfilling the IIASA Strategy’s aim of strengthening partnerships, I look forward to continuing to interact with IIASA researchers and supporting the institute’s goals of making sure the work done at IIASA positively impacts society. So come and chat with me!

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 18, 2021 | Austria, Climate, Climate Change, Communication, Education, Health

By Thomas Schinko, Acting Research Group Leader, Equity and Justice Research Group

Thomas Schinko introduces an innovative and transdisciplinary peer-to-peer training program.

What do we want – climate justice! When do we want it – now! The recent emergence of youth-led, social climate movements like #FridaysForFuture (#FFF), the Sunrise Movement, and Extinction Rebellion has reemphasized that at the heart of many – if not all – grand global challenges of our time, lie aspects of social and environmental justice. With a novel peer-to-peer education format, embedded in a transdisciplinary research project, the Austrian climate change research community responds to the call that unites these otherwise diverse movements: “Listen to the Science!”

The climate crisis raises several issues of justice, which include (but are not limited to) the following dimensions: First, intragenerational climate justice addresses the fair distribution of costs and benefits associated with climate change mitigation and adaptation, as well as the rectification of damage caused by residual climate change impacts between present generations. Second, intergenerational justice focuses on the distribution of benefits and costs from climate change between present and future generations. Third, procedural justice asks for fair processes, namely that institutions allow all interested and affected actors to advance their claims while co-creating a low-carbon future. Movements like #FFF maneuver at the intersection of those three forms of climate justice when calling on policy- and decision makers to urgently take climate action, since “there is no planet B”.

Along with the emergence of these youth-led social climate movements came an increasing demand for the expertise of scientists working in the fields of climate change and sustainability research. To support #FFF’s claims with the best available scientific evidence, a group of German, Austrian, and Swiss scientists came together in early 2019 as Scientists for Future. Since then, requests from students, teachers, and policy and decision makers for researchers to engage with the younger generation have soared, also in Austria. Individual researchers like me have not been able to respond to all these requests at the extent we would have liked to.

In this situation of high demand for scientific support, the Climate Change Center Austria (CCCA) and The Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Research (BMBWF) have put their heads together and established a transdisciplinary research project – makingAchange. By engaging early on with our potential end users – Austrian school students – a truly transdisciplinary team of researchers as well as practitioners in youth participation and education (the association “Welt der Kinder”) has co-developed this novel peer-to-peer curriculum. The training program, which runs over a full school year, sets out to provide the students not only with solid scientific facts but also with soft skills that are needed for passing on this knowledge and for building up their own climate initiatives in their schools and municipalities. One of the key aims is to provide solid scientific support while not overburdening the younger generation who often tend to put too high demands on themselves.

Establishing scientific facts about climate change and offering scientific projections of future change on its own does not drive political and societal change. Truly inter- and transdisciplinary research is needed to support the complex transformation towards a sustainable society and the integration of novel, bottom-up civil society initiatives with top-down policy- and decision making. Engaging multiple actors with their alternative problem frames and aspirations for sustainable futures is now recognized as essential for effective governance processes, and ultimately for robust policy implementation.

Also, in the context of makingAchange it is not sufficient to communicate science to students in order to generate real-world impact in terms of leading our societies onto low-carbon development pathways. What is additionally needed, is to provide them with complementary personal and social skills for enhancing their perceived self-efficacy and response efficacy, which is crucial for eventually translating their knowledge into real climate action in their respective spheres of influence.

Recent insights from a medical health assessment of the COVID-19 related lockdowns on childhood mental health in the UK have shown that we are engaging in an already highly fragile environment. In addition, a recent representative study for Austria has shown that the pandemic is becoming a psychological burden. The study authors are particularly concerned about young people; more than half of young Austrians are already showing symptoms of depression. Hence, we must engage very carefully with the makingAchange students when discussing the drivers and potential impacts of the climate crises. Particularly since some of them are quite well informed about research, which has shown (by using a statistical approach) that our chances of achieving the 1.5 to 2°C target stipulated in the Paris Agreement are now probably lower than 5%. Another example of such alarming research insights comes in the form of a 2020 report by the World Meteorological Organization, which warns that there is a 24% chance that global average temperatures could already surpass the 1.5°C mark in the next five years.

Zoom group picture taken at the end of the second online makingAchange workshop for Austrian school students. Copyright: makingAchange

The first makingAchange activities and workshops have now taken place – due to the COVID-19 regulations in an online format, which added further complexity to this transdisciplinary research project. Nevertheless, we were able to discuss some of the hot topics that the young people were curious about, such as the natural science foundations of the climate crisis, climate justice, or a healthy and sustainable diet. At the same time, we provided our students with skills to further transmit this knowledge and to take climate action in their everyday live – such as a climate friendly Christmas celebration in 2020. The school student’s lively engagement in these sessions as well as the overall positive (anonymous) feedback has proven that we are on the right track.

The role of science is changing fast from “advisor” to “partner” in civil society, policymaking, and decision making. By doing so, scientists can play an important, active role in implementing the desperately needed social-ecological transformation of our society without becoming policy prescriptive. With the makingAchange project, we are actively engaging in this transformational process – currently only in Austria but with high ambitions to scale-out this novel peer-to-peer format to other geographical and cultural contexts.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 16, 2021 | Communication, Data and Methods, IIASA Network

By Luke Kirwan, IIASA Repository and Open Access Manager

IIASA Repository and Open Access Manager Luke Kirwan explains the ins-and-outs of the Plan S policy towards full and immediate Open Access publishing.

With Plan S, which has been implemented from 1 January 2021, new Open Access requirements come into force for project participants, which are intended to accelerate the transformation to complete and immediate Open Access. This has implications for researchers obtaining funding from funders supporting Plan S, such as the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) or Formas (a Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development).

What exactly is Plan S?

Plan S is an initiative that aims to promote making research immediately open access without embargo periods or restrictions. It requires that, from 2021, scientific publications that result from research funded by public grants must be published in compliant Open Access journals or platforms. A number of national and international research bodies, including the FWF and the European Research Council (ERC), are working jointly on the implementation of Plan S and the promotion of open access research publication. A list of these funding bodies can be found here and more detailed information on the implementation of Plan S is available here.

What you need to know

What you need to know

Starting from 1 January 2021, publications derived from research funded by Plan S research organizations must be made openly accessible immediately upon publication without any embargo period. This applies only to projects submitted after 1 January 2021. Furthermore, this material must be made available under a Creative Commons Attribution license (CC-BY). In some instances, a more restrictive license can be applied, but this must be discussed with the funding body.

Further guidelines are currently being developed for publications that are not journal articles such as books and edited volumes. From 2021 onwards, it is important to closely check the requirements of research funders to ensure that projects are compliant with any open access requirements they may have.

Further guidelines are currently being developed for publications that are not journal articles such as books and edited volumes. From 2021 onwards, it is important to closely check the requirements of research funders to ensure that projects are compliant with any open access requirements they may have.

Papers published under Plan S funding has to include an appropriate acknowledgement. In the case of FWF funded research, it must for example follow the following format:

‘This research was funded in whole, or in part, by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) [Grant number]. For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright license to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.’

Authors of papers published under Plan S funding will retain the copyright of their work, and will be providing journals with a license to publish their material rather than fully transferring copyright to them. Publishers that require a license to publish must allow the authors to make either the published version, or the accepted version, immediately available under an open license. No embargo period is permitted.

Routes to compliance

- Publish in an open access journal

- Make the accepted manuscript immediately available in an open access repository (like PURE) under a CC-BY license

- Publish in a subscription journal where IIASA has an open access agreement (For a list of IIASA’s current agreements please see here)

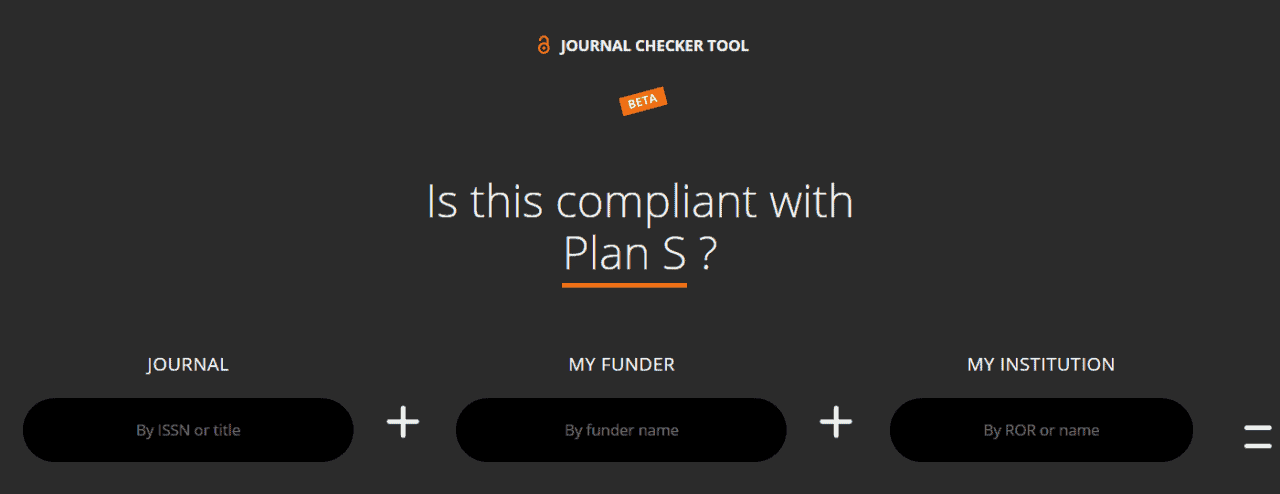

COAlition S has provided a journal checker tool so that you can check a journals compliance with the Plan S requirements.

The FWF’s statement and guidelines for Plan S can be found here. The operation and success of Plan S will be reviewed by the end of 2024. For any further information or assistance, please contact the library.

Related links:

Science family of journals announces change to open-access policy (Jan 2021)

Nature journals reveal terms of landmark open-access option (NOV 2020)

Plan S toolkit (coalition S website)

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Sep 18, 2020 | Data and Methods, Science and Policy, Systems Analysis

By Daniel Huppmann, research scholar in the IIASA Energy Program

Daniel Huppmann sheds light on how open-source scientific software and FAIR data can bring us one step closer to a community of open science.

© VectorMine | Dreamstime.com

Over the past decade, the open-source movement (e.g., the Free Software Foundation (FSF) and the Open Source Initiative (OSI)) has had a tremendous impact on the modeling of energy systems and climate change mitigation policies. It is now widely expected – in particular by and of early-career researchers – that data, software code, and tools supporting scientific analysis are published for transparency and reproducibility. Many journals actually require that authors make the underlying data available in line with the FAIR principles – this acronym stands for findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable. The principles postulate best-practice guidance for scientific data stewardship. Initiatives such as Plan S, requiring all manuscripts from projects funded by the signatories to be released as open-access publications, lend further support to the push for open science.

Alas, the energy and climate modeling community has so far failed to realize and implement the full potential of the broader movement towards collaborative work and best practice of scientific software development. To live up to the expectation of truly open science, the research community needs to move beyond “only” open-source.

Until now, the main focus of the call for open and transparent research has been on releasing the final status of scientific work under an open-source license – giving others the right to inspect, reuse, modify, and share the original work. In practice, this often means simply uploading the data and source code for generating results or analysis to a service like Zenodo. This is obviously an improvement compared to the previously common “available upon reasonable request” approach. Unfortunately, the data and source code are still all too often poorly documented and do not follow best practice of scientific software development or data curation. While the research is therefore formally “open”, it is often not easily intelligible or reusable with reasonable effort by other researchers.

What do I mean by “best practice”? Imagine I implement a particular feature in a model or write a script to answer a specific research question. I then add a second feature – which inadvertently changes the behavior of the first feature. You might think that this could be easily identified and corrected. Unfortunately, given the complexity and size to which scientific software projects tend to quickly evolve, one often fails to spot the altered behavior immediately.

One solution to this risk is “continuous integration” and automated testing. This is a practice common in software development: for each new feature, we write specific tests in an as-simple-as-possible example at the same time as implementing the function or feature itself. These tests are then executed every time that a new feature is added to the model, toolbox, or software package, ensuring that existing features continue to work as expected when adding a new functionality.

Other practices that modelers and all researchers using numerical methods should follow include using version control and writing documentation throughout the development of scientific software rather than leaving this until the end. In addition, not just the manuscript and results of scientific work should be scrutinized (aka “peer review”), but such appraisal should also apply to the scientific software code written to process data and analyze model results. In addition, like the mentoring of early-career researchers, such a review should not just come at the end of a project but should be a continuous process throughout the development of the manuscript and the related analysis scripts.

In the course that I teach at TU Wien, as well as in my work on the MESSAGEix model, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C scenario ensemble, and other projects at the IIASA Energy Program, I try to explain to students and junior researchers that following such best-practice steps is in their own best interest. This is true even when it is just a master’s thesis or some coursework assignment. However, I always struggle to find the best way to convince them that following best practice is not just a noble ideal in itself, but actually helps in doing research more effectively. Only when one has experienced the panic and stress caused by a model not solving or a script not running shortly before a submission deadline can a researcher fully appreciate the benefits of well-structured code, explicit dependencies, continuous integration, tests, and good documentation.

A common trope says that your worst collaborator is yourself from six months ago, because you didn’t write enough explanatory comments in your code and you don’t respond to emails. So even though it sounds paradoxical at first, spending a bit more time following best practice of scientific software development can actually give you more time for interesting research. Moreover, when you then release your code and data under an open-source license, it is more likely that other researchers can efficiently build on your work – bringing us one step closer to a community of open science!

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 5, 2020 | Biodiversity, Data and Methods, Ecosystems, Young Scientists

By Martin Jung, postdoctoral research scholar in the IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program.

IIASA postdoc Martin Jung discusses how a newly developed map can help provide a detailed view of important species habitats, contribute to ongoing ecosystem threat assessments, and assist in biodiversity modeling efforts.

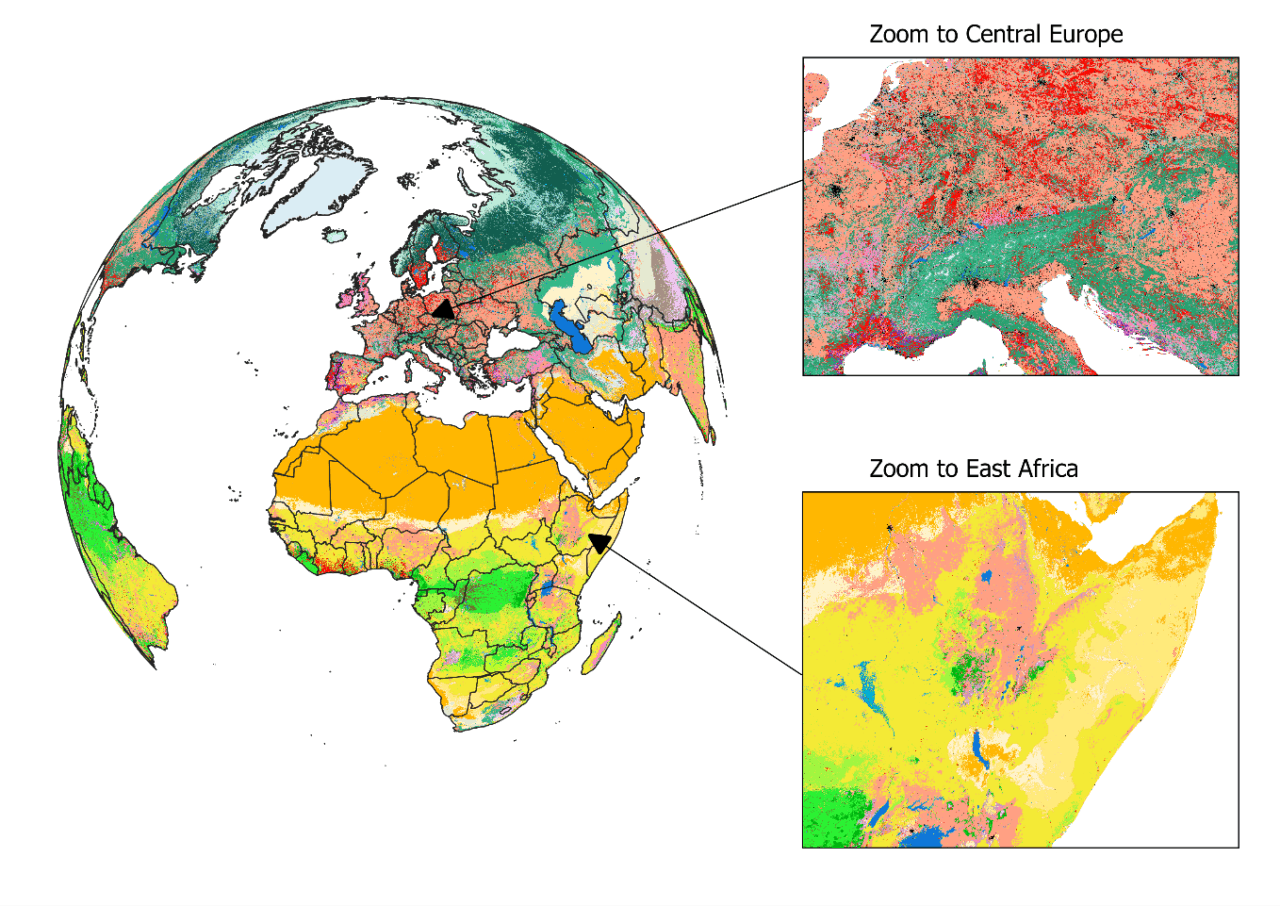

Biodiversity is not evenly distributed across our planet. To determine which areas potentially harbor the greatest number of species, we need to understand how habitats valuable to species are distributed globally. In our new study, published in Nature Scientific Data, we mapped the distribution of habitats globally. The habitats we used are based on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List habitat classification scheme, one of the most widely used systems to assign species to habitats and assess their extinction risk. The latest map (2015) is openly available for download here. We also built an online viewer using the Google Earth Engine platform where the map can be visually explored and interacted with by simply clicking on the map to find out which class of habitat has been mapped in a particular location.

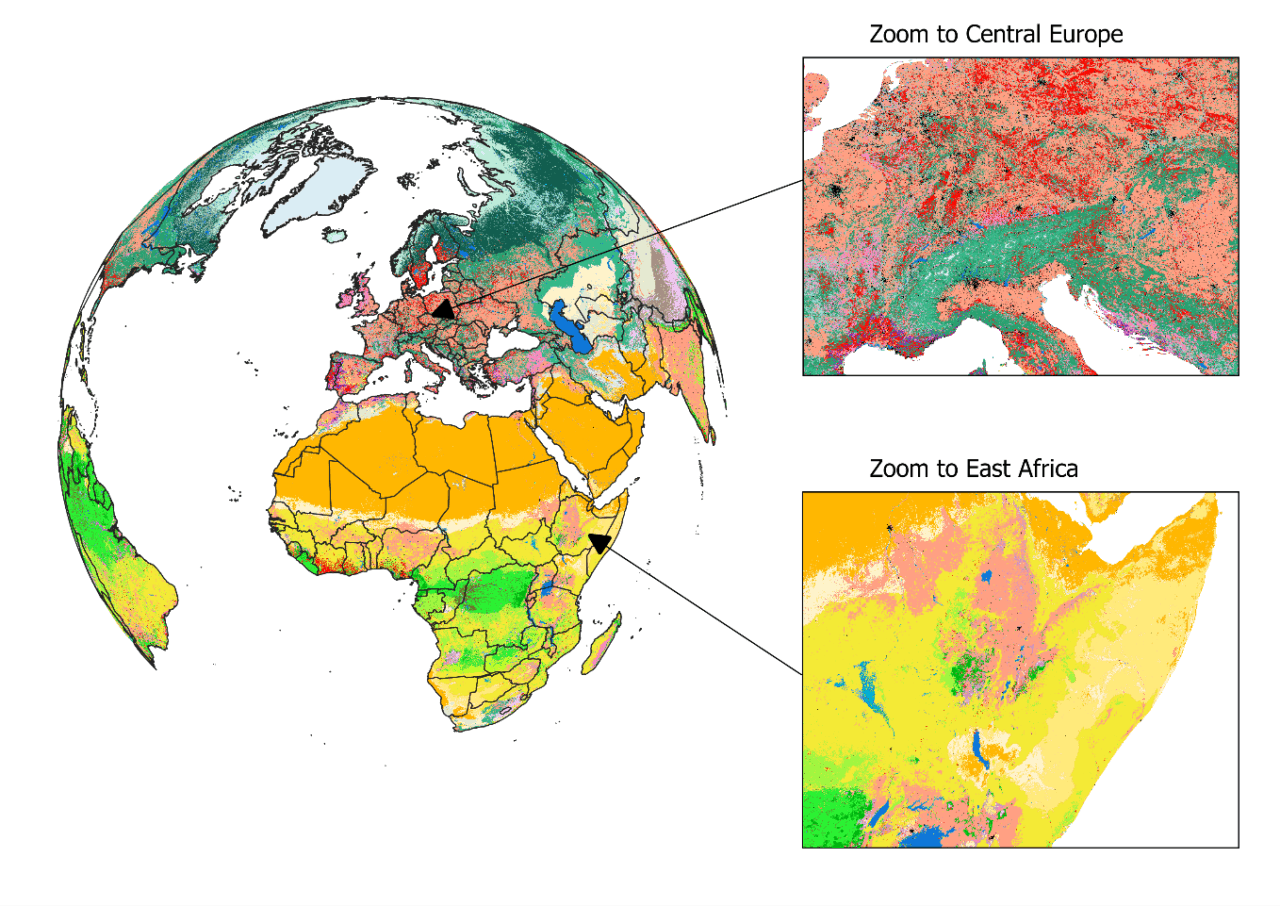

Figure 1: View on the habitat map with focus on Europe and Africa. For a global view and description of the current classes mapped, please read Jung et al. 2020 or have a look at the online interactive interface.

The habitat map was created as an intersection of various, best-available layers on land cover, climate, and land use (Figure 1). Specifically, we created a decision tree that determines for each area on the globe the likely presence of one of currently 47 mapped habitats. For example, by combining data on tropical climate zones, mountain regions and forest cover, we were able to estimate the distribution of subtropical/tropical moist mountainous rain forests, one of the most biodiverse ecosystems. The habitat map also considers best available land use data to map human modified or artificial habitats such as rural gardens or urban sites. Notably, and as a first, our map also integrates upcoming new data on the global distribution of plantation forests.

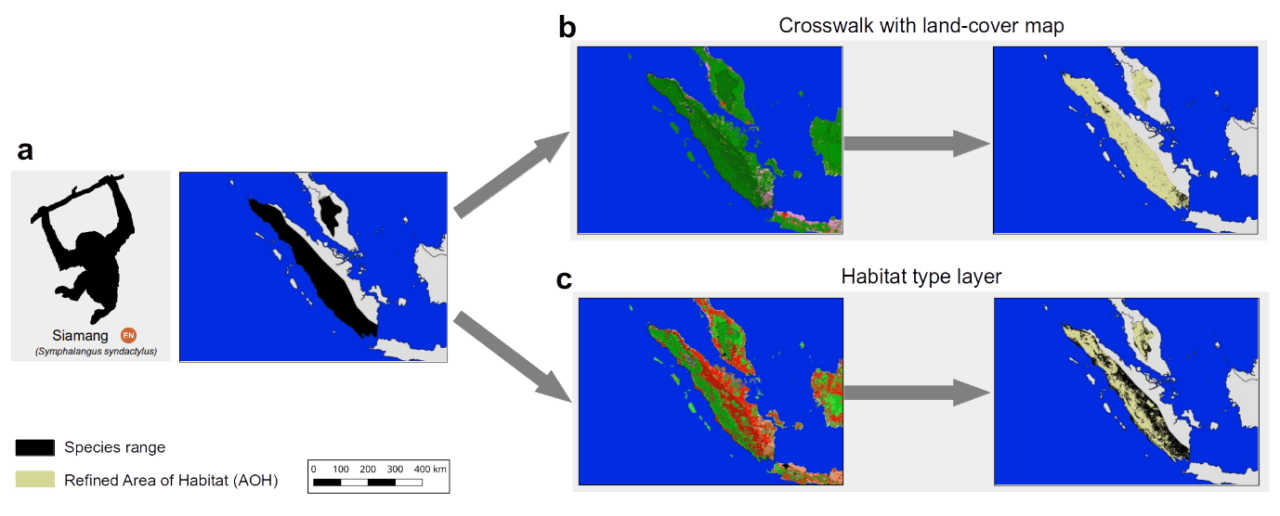

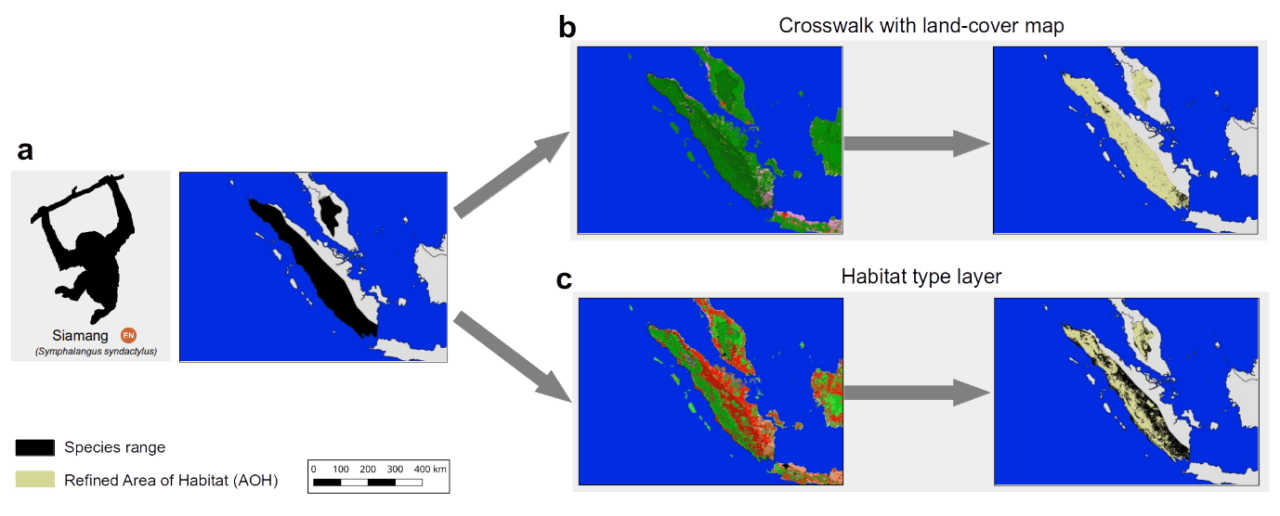

What makes this map so useful for biodiversity assessments? It can provide a detailed view on the remaining coverage of important species habitats, contribute to ongoing ecosystem threat assessments, and assist in global and national biodiversity modeling efforts. Since the thematic legend of the map – in other words the colors, symbols, and styles used in the map – follows the same system as that used by the IUCN for assessing species extinction risk, we can easily refine known distributions of species (Figure 2). Up to now, such refinements were based on crosswalks between land cover products (Figure 2b), but with the additional data integrated into the habitat map, such refinements can be much more precise (Figure 2c). We have for instance conducted such range refinements as part of the Nature Map project, which ultimately helped to identify global priority areas of importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Figure 2: The range of the endangered Siamang (Symphalangus syndactylus) in Indonesia and Malaysia according to the IUCN Red List. Up to now refinements of its range were conducted based on land cover crosswalks (b), while the habitat map allows a more complete refinement (c).

Similar as with other global maps, this new map is certainly not without errors. Even though a validation has proved good accuracy at high resolution for many classes, we stress that – given the global extent and uncertainty – there are likely fine-scale errors that propagate from some of the input data. Some, such as the global distribution of pastures, are currently clearly insufficient, with existing global products being either outdated or not highly resolved enough to be useful. Luckily, with the decision tree being implemented on Google Earth Engine, a new version of the map can be created within just two hours.

In the future, we plan to further update the habitat map and ruleset as improved or newer data becomes available. For instance, the underlying land cover data from the European Copernicus Program is currently only available for 2015, however, new annual versions up to 2018 are already being produced. Incorporating these new data would allow us to create time series of the distribution of habitats. There are also already plans to map currently missing classes such as the IUCN marine habitats – think for example of the distribution of coral reefs or deep-sea volcanoes – as well as improving the mapped wetland classes.

Lastly, if you, dear reader, want to update the ruleset or create your own habitat type map, then this is also possible. All input data, the ruleset and code to fully reproduce the map in Google Earth Engine is publicly available. Currently the map is at version 003, but we have no doubt that the ruleset and map can continue to be improved in the future and form a truly living map.

Reference:

Jung M, Raj Dahal P, Butchart SHM, Donald PF, De Lamo X, Lesiv M, Kapos V,Rondinini C, & Visconti P (2020). A global map of terrestrial habitat types. Nature Scientific Data DOI: 10.1038/s41597-020-00599-8

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.