Feb 14, 2020 | China, Environment, Food & Water, Water, Women in Science

By Maryna Strokal, Department of Environmental Sciences, Water Systems and Global Change, Wageningen University and Research, The Netherlands

Maryna Strokal discusses a new integrated approach to finding cost-effective solutions for nutrient pollution and coastal eutrophication developed with IIASA colleagues.

© Huy Thoai | Dreamstime.com

Have you ever wondered why the water in some rivers appear to be green? The green tinge you see is due to eutrophication, which means that too many nutrients – specifically nitrogen and phosphorus – are present in the water. This happens because rivers receive these nutrients from various land-based activities like run-off from agricultural fields and sewage effluents from cities. Rivers in turn export many of these nutrients to coastal waters, where it serves as food for algae. Too many nutrients, however, cause the algae and their blooms to grow more than normal. Because algae consumes a lot of oxygen, this lowers the available oxygen supply in the water, killing off fish and other marine life. Some algae can also be toxic to people when they eat seafood that have been exposed to, or fed on it. Polluted river water on the other hand, is unfit for direct use as drinking water, or for cooking, showering, or any of our other daily needs. Before we can use this water, it needs to be treated, which of course costs money.

To better understand and address these issues, I worked with colleagues from IIASA, Wageningen University, and China to develop an integrated approach to identify cost-effective solutions (read cheapest) to reduce river pollution and thus coastal eutrophication. Our integrated approach takes into account human activities on land, land use, the economy, the climate, and hydrology. We implemented the new approach for the Yangtze Basin in China.

The Yangtze is the third longest river in the world and exports nutrients from ten sub-basins to the East China Sea, where the coast often experiences severe eutrophication problems that may increase in the coming years. The Chinese government has called for effective actions to ensure clean water for both people and nature.

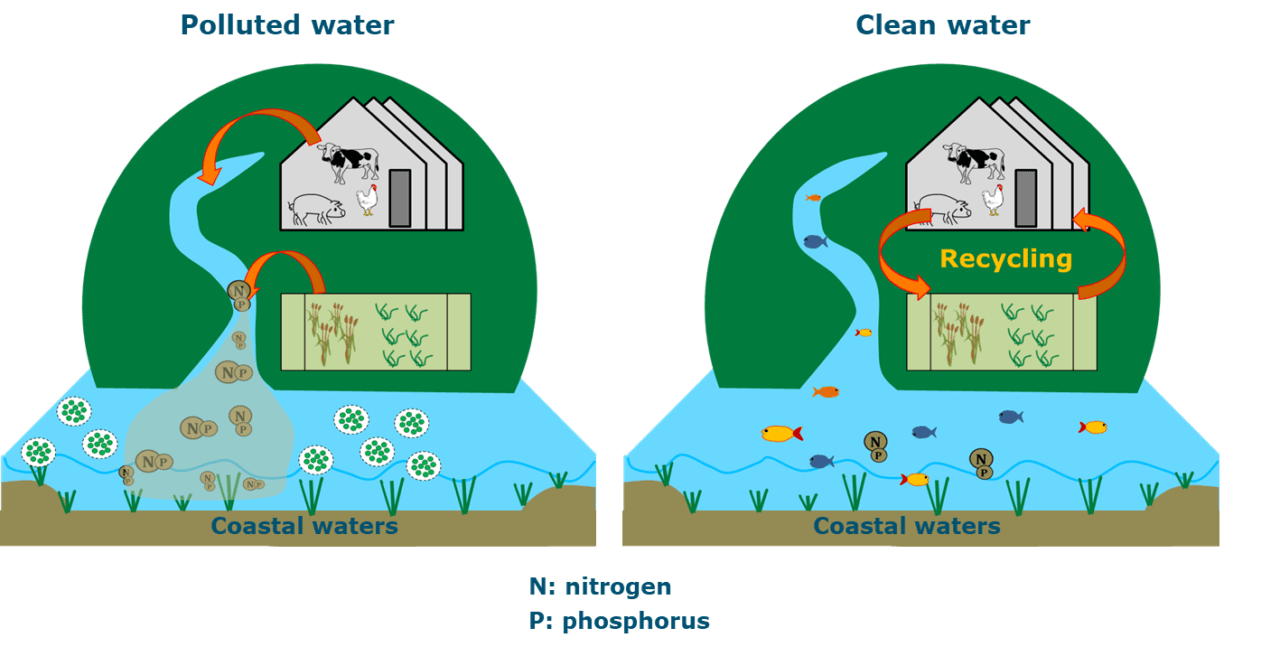

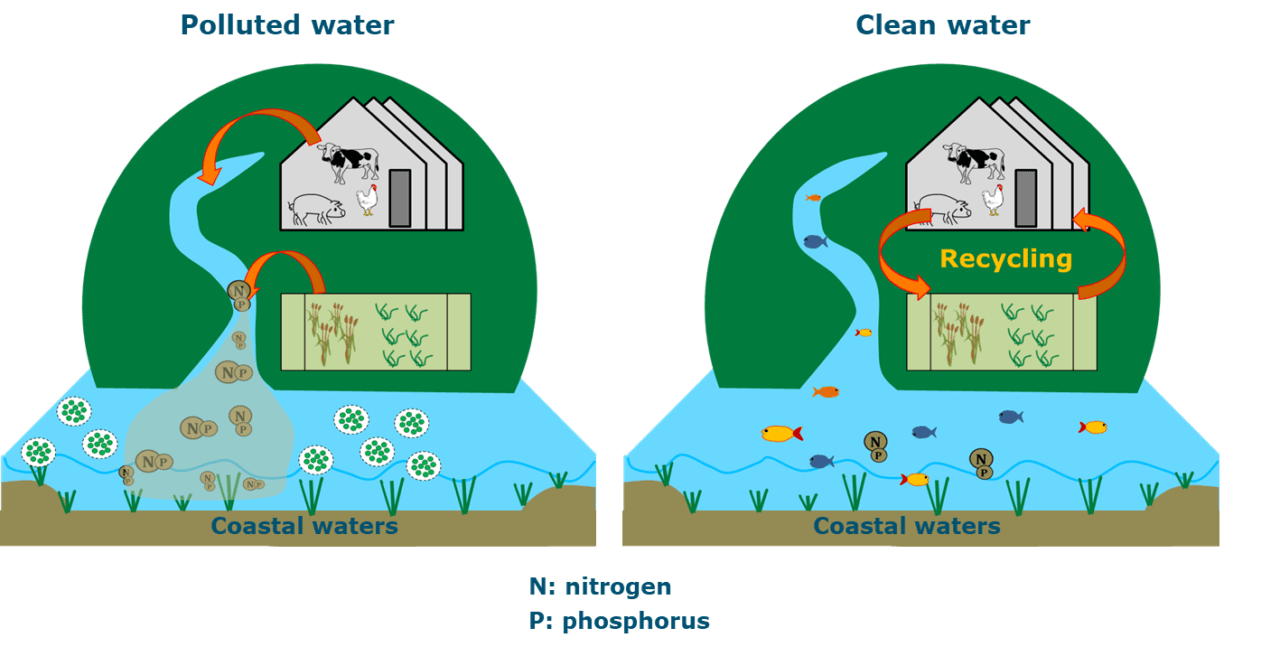

In our paper on this work, which was recently published in the journal Resources, Conservation, and Recycling, my colleagues and I conclude that reducing more than 80% of nutrient pollution in the Yangtze will cost US$ 1–3 billion in 2050. This cost might seem high, but it is actually far below 10% of the income level in the Yangtze basin. We also identified an opportunity in the negative or zero cost range, which would result in a below 80% reduction in nutrient export by the Yangtze. This negative or zero cost alternative involves options to recycle manure on land and reduce the use of chemical fertilizers (Figure 1). More recycling means that farmers will buy less chemical fertilizers and potential savings can then compensate for the expenses related to recycling the manure. We also illustrated the costs that would be involved for ten sub-basins to reduce their nutrient export to coastal waters.

Figure 1. Summarized illustration of eutrophication causes and cost-effective solutions for reducing nutrient export by Yangtze and thus coastal eutrophication in the East China Sea in 2050.

Recycling manure on cropland is an important and cost-effective solution for agriculture in the sub-basins of the Yangtze River (Figure 1). Manure is rich in the nutrients that crops need, and opting for this alternative instead of chemical fertilizers avoids loss of nutrients to rivers, and thus ultimately to coastal waters. Current practices are however still far from ideal, with manure – and especially liquid manure – often being discharged into water because crop and livestock farms are far away from each other, which makes it practically and economically difficult to transport manure to where it is needed. Another reason is the historical practice of farmers using chemical fertilizers on their crops – it is simply how they are used to doing things. Unfortunately, the amounts of fertilizers that farmers apply are often far above what crops actually need, thus leading to river pollution.

The Chinese government are investing in combining crop and livestock production, in other words, they are creating an agricultural sector where crops are used to feed animals and manure from the animals is in turn used to fertilize crops. Chinese scientists are working with farmers to implement these solutions.

In our paper, we showed that these solutions are not only sustainable, but also cost-effective in terms of avoiding coastal eutrophication. We invite you to read our paper for more details.

References

Strokal M, Kahil T, Wada Y, Albiac J, Bai Z, Ermolieva T, Langan S, Ma L, et al. (2020). Cost-effective management of coastal eutrophication: A case study for the Yangtze River basin. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 154: e104635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104635.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 21, 2019 | Air Pollution, Environment, Food & Water, Indonesia, Women in Science

By Adriana Gómez-Sanabria, researcher in the IIASA Air Quality and Greenhouse Gases Program

Adriana Gómez-Sanabria discusses the results of a new study that looked into the impacts of implementing various technologies to treat wastewater from the fish processing industry in Indonesia.

© Mikhail Dudarev | Dreamstime.com

To reduce water pollution and climate risks, the world needs to go beyond signing agreements and start acting. Translating agreements and policies into action is however always much more difficult than it might seem, because it requires all players involved to participate. A complete integration strategy across all sectors is needed. One of the advantages of integrating all sectors is that it would be possible to meet different objectives, for example, climate and water protection goals in this case, with the same strategy.

I was involved in a study that assessed the impacts of implementing various technologies to treat wastewater from the fish processing industry in Indonesia when involving different levels of governance. This study is part of the strategies that the government of Indonesia is evaluating to meet the greenhouse gas mitigation goals pledged in its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), as well as to reduce water pollution. Although Indonesia has severe national wastewater regulations, especially in the fish processing industry, these are not being strictly implemented due to lack of expertise, wastewater infrastructure, budgetary availability, and lack of stakeholder engagement. The objective of the study was to evaluate which technology would be the most appropriate and what levels of governance would need to be involved to simultaneously meet national climate and water quality targets in the country.

Seven different wastewater treatment technologies and governance levels were included in the analysis. The combinations included were: 1) Untreated/anaerobic lagoons – where untreated means wastewater is discharged without any treatment and anaerobic lagoons are ponds filled with wastewater that undergo anaerobic processes – combined with the current level of governance. 2) Aeration lagoons – which are wastewater treatment systems consisting of a pond with artificial aeration to promote the oxidation of wastewaters, plus activated sludge focused solely on water quality targets with no coordination between water and climate institutions. 3) Swimbed, which is an aerobic aeration tank focusing mainly on climate targets assuming no coordination between institutions. 4) Upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) technology, which is an anaerobic reactor with gas recovery and use followed by Swimbed, and 5) UASB with gas recovery and use followed by activated sludge, which is an aerobic treatment that uses microorganisms forming particles that clump together. Both, 4 and 5 assume vertical and horizontal coordination between water and climate institutions at national, regional, and local level. It is important to notice that the main difference between 4 and 5 is the technology used in the second step. Two additional combinations, 6 and 7, are also proposed including the same technological combinations of 4 and 5, but these include increasing the level of governance to a multi-actor coordination level. The multi-actor level includes coordination at all institutional levels but also involves academia, research institutes, international support, and other stakeholders.

Our results indicate that if the current situation continues, there would be an increase of greenhouse gases and water pollution between 2015 and 2030, driven by the growth in fish industry production volumes. Interestingly, the study also shows that focusing only on strengthening capacities to enforce national water policies would result in greenhouse gas emissions five times higher in 2030 than if the current situation continues, due to the increased electricity consumption and sludge production from the wastewater treatment process. The benefit of this strategy would be positive for the reduction of water pollution, but negative for climate change mitigation. From our analyses of combinations 2 and 3 we learned that technology can be very efficient for one purpose but detrimental for others. If different institutions are, for example, responsible for water quality and climate change mitigation, communication between the institutions is crucial to avoid trade-offs between environmental objectives.

Furthermore, when analyzing different cooperation strategies together with a combination of diverse sets of technologies, we found that not all combinations work appropriately. For instance, improving interaction just within and between institutions does not guarantee proper selection and application of technologies. In this case, the adoption of the technology is not fast enough to meet the targets proposed in 2030, thus resulting in policy implementation failures. Our analyses of combinations 4 and 5 showed that interaction within and between national, regional, and local institutions alone is not enough to prevent policy failure.

Finally, a multi-actor cooperation strategy that includes cooperation across sectors, administrative levels, international support, and stakeholders, seems to be the right approach to ensure selection of the most appropriate technologies and achieve policy success. We identified that with this approach, it would be possible to reduce water pollution and simultaneously decrease greenhouse gas emissions from the electricity required for wastewater treatment. Analyzing combinations 6 and 7 revealed that multi-actor governance allows to simultaneously meet climate and water objectives and a high chance to prevent policy failure.

In the end, analyses such as the one shown here, highlight the importance of integrating and creating synergies across sectors, administrative levels, stakeholders, and international institutions to ensure an effective implementation of policies that provide incentives to make careful choices regarding multi-objective treatment technologies.

Reference:

Gómez-Sanabria A, Zusman E, Höglund-Isaksson L, Klimont Z, Lee S-Y, Akahoshi K, Farzaneh H, & Chairunnisa (2019). Sustainable wastewater management in Indonesia’s fish processing industry: bringing governance into scenario analysis. Journal of Environmental Management (Submitted).

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Sep 23, 2019 | Ecosystems, Environment, Sustainable Development

By Frank Sperling, Senior Project Manager (FABLE) in the IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program

Food and land use systems play a critical role in managing climate risks and bringing the world onto a sustainable development trajectory.

The UN Secretary General’s Climate Action Summit in New York on 23 September seeks to catalyze further momentum for climate change mitigation and adaptation. The transformation of the food and land use system will play a critical role in managing climate risks and bringing the world onto a sustainable development trajectory.

Today’s food and land use systems are confronted with a great variety of challenges. This includes delivering on universal food security and better diets by 2030. Over the last decades, great strides have been made towards achieving universal food security, but this progress recently grinded to a halt. The number of people suffering from chronic hunger has been rising again from below 800 million in 2015 to over 820 million people today [1]. Food security is however not only about a sufficient supply of calories per person. It is also about improving diets, addressing the worldwide increase in the prevalence of obesity, and how we use and value environmental goods and services.

© Paulus Rusyanto | Dreamstime.com

Agriculture, forestry and other land use currently account for around 24% of greenhouse gas emissions caused by human activities [2]. Land use changes are also a major driver behind the worldwide loss of biodiversity [3]. Clearly, in light of population growth and the increasingly visible fingerprints of a human-induced global climate crisis and other environmental changes, business as usual is not an option.

Systems thinking is key in shifting towards more sustainable practices. A new report released by the Food and Land-Use System (FOLU) Coalition showcases that there is much to be gained. There are massive hidden costs in our current food and land use systems. The report outlines ten critical transitions, which can substantially reduce these hidden costs, thereby generating an economic prize, while improving human and planetary health.

The International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) contributed to the analytics underpinning the report [4], applying the Global Biosphere Management Model (GLOBIOM) [5]. A “better futures” scenario, which seeks to collectively address development and environmental objectives, was compared to a “current trends” scenario, which is basically a continuation of a business-as-usual scenario. The assessment illustrates that an integrated approach that acknowledges the interactions in the food and land use space, can help identify synergies and manage trade-offs across sectors. For example, shifting towards healthy diets not only improves human health, but also reduces pressure on land, thereby helping to improve the solution space for addressing climate change and halting biodiversity loss.

While understanding that the global picture is important, practical solutions require engagement with national and subnational governments. The challenge is to identify development pathways that address the development needs and aspirations of countries within global sustainability contexts. As part of FOLU, the Food, Agriculture, Biodiversity, Land and Energy (FABLE) Consortium was initiated to do exactly this. The FABLE Secretariat, jointly hosted by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) and IIASA, is working with knowledge institutions from developed and developing countries, to explore the interactions between national and global level objectives and their implications for pathways towards sustainable food and land use systems. Preliminary results from inter-active scenario and development planning exercises, so-called Scenathons, were recently presented in the FABLE 2019 report.

These initiatives highlight that acknowledging and embracing complexity can help reconcile development and environmental interests. This also entails rethinking how we relate to and manage nature’s services and their role in providing the foundation for the welfare of current and future generations. This is underscored by the prominent role nature-based solutions are given at the UN Secretary General’s Climate Action Summit. We need to move from silo-based, sector specific, single objective approaches to a focus on multiple objective solutions. In the land use space, this means embedding agriculture in the broader land use context, which accounts for and values environmental services, and linking to the food system where dietary choices shape human health and the demand for land.

Doing so will help bridge the international policy objectives of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the UN Convention on Combating Desertification (UNCCD), the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) enshrined in ‘The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’. This represents an opportunity to create a new value proposition for agriculture and other land use activities where environmental stewardship is rewarded.

References

[1] Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) et al. (2019). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2019. Safeguarding against economic slowdowns and downturns. Rome, FAO.

[2] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2019). Climate Change and Land. IPCC Special Report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

[3] Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) (2018). The IPBES assessment report on land degradation and restoration. Montanarella, L., Scholes, R., and Brainich, A. (eds.). Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Bonn, Germany. 744 pages.

[4] Deppermann, A. et al. 2019. Towards sustainable food and land-use systems: Insights from integrated scenarios of the Global Biosphere Management Model (GLOBIOM). Supplemental Paper to The 2019 Global Consultation Report of the Food and Land Use Coalition Growing Better: Ten Critical Transitions to Transform Food and Land Use. Laxenburg, IIASA.

[5] Havlik P, Valin H, Herrero M, Obersteiner M, Schmid E, Rufino MC, Mosnier A, Thornton PK, et al. (2014). Climate change mitigation through livestock system transitions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111 (10): 3709-3714. DOI: 1073/pnas.1308044111 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/10970].

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Mar 29, 2019 | USA, Young Scientists

By Matt Cooper, PhD student at the Department of Geographical Sciences, University of Maryland, and 2018 winner of the IIASA Peccei Award

I never pictured myself working in Europe. I have always been an eager traveler, and I spent many years living, working and doing fieldwork in Africa and Asia before starting my PhD. I was interested in topics like international development, environmental conservation, public health, and smallholder agriculture. These interests led me to my MA research in Mali, working for an NGO in Nairobi, and to helping found a National Park in the Philippines. But Europe seemed like a remote possibility. That was at least until fall 2017, when I was looking for opportunities to get abroad and gain some research experience for the following summer. I was worried that I wouldn’t find many opportunities, because my PhD research was different from what I had previously done. Rather than interviewing farmers or measuring trees in the field myself, I was running global models using data from satellites and other projects. Since most funding for PhD students is for fieldwork, I wasn’t sure what kind of opportunities I would find. However, luckily, I heard about an interesting opportunity called the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) at IIASA, and I decided to apply.

Participating in the YSSP turned out to be a great experience, both personally and professionally. Vienna is a wonderful city to live in, and I quickly made friends with my fellow YSSPers. Every weekend was filled with trips to the Alps or to nearby countries, and IIASA offers all sorts of activities during the week, from cultural festivals to triathlons. I also received very helpful advice and research instruction from my supervisors at IIASA, who brought a wealth of experience to my research topic. It felt very much as if I had found my kind of people among the international PhD students and academics at IIASA. Freed from the distractions of teaching, I was also able to focus 100% on my research and I conducted the largest-ever analysis of drought and child malnutrition.

© Matt Cooper

Now, I am very grateful to have another summer at IIASA coming up, thanks to the Peccei Award. I will again focus on the impact climate shocks like drought have on child health. however, I will build on last year’s research by looking at future scenarios of climate change and economic development. Will greater prosperity offset the impacts of severe droughts and flooding on children in developing countries? Or does climate change pose a hazard that will offset the global health gains of the past few decades? These are the questions that I hope to answer during the coming summer, where my research will benefit from many of the future scenarios already developed at IIASA.

I can’t think of a better research institute to conduct this kind of systemic, global research than IIASA, and I can’t picture a more enjoyable place to live for a summer than Vienna.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 2, 2018 | Citizen Science, Ecosystems, Environment, Food

by Rastislav Skalsky, Ecosystems Services and Management Program, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis

Clay soil

As growers, we know soil is important. It supports plants, and provides nutrients and water for them to grow. But do we all appreciate how crucial the role of soil is in continuously supplying plants with water, even when it hasn’t rained for a few days or even weeks, even without extra water being added via watering?

Soil is like a sponge. It can retain rain water and, if it is not taken up by plants, soil can store it for a long time. We can feel the water in soil as soil moisture. Try it — take and hold a lump (clod) of soil — if it is wet it will leave a spot on your palm. If it’s only moist then it will feel cold — cooler than the air around. And if the soil is dry, it will feel a little warm.

Soil moisture not only can be felt, but it can also be measured — in the lab, or directly in the field with professional or low-cost soil moisture sensors.

Soil moisture in general indicates how much water is contained by the soil. But it is not always the case that soil which feels moist or wet is able to support plants. It could happen that, despite feeling moist, the soil simply does not hold enough water, or holds the water too tightly for the plants to extract it. Or the opposite, soil can sometimes contain too much water. To understand how this works, one has to learn more about how water is stored in the soil.

Water is bound to soil by physical forces. Some forces are too weak to hold water in the plant root zone and water percolates to deeper layers, where plants can no longer reach it. Other forces can be too strong, preventing water from being retrieved by the roots.

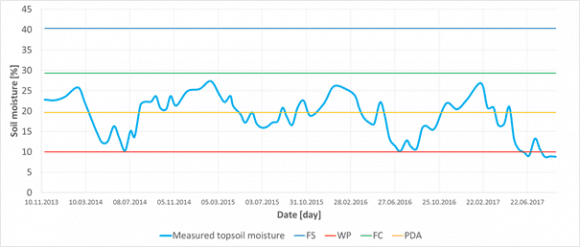

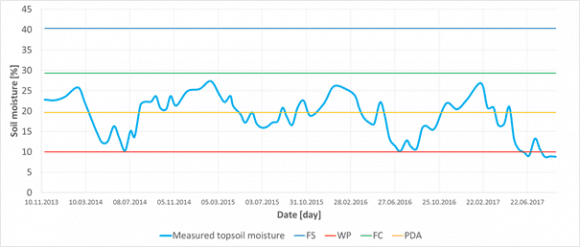

Figure 1

If soil moisture is measured at one place over time, it can reveal its seasonal dynamics. Having estimated important soil water content thresholds (FS — full saturation, FC — field capacity, PDA — point of decreased availability, and WP — wilting point) for that particular site, e.g. based on soil texture test or measurement, one can easily interpret if the measured soil moisture and say if there was enough water or not to fully support plants with water and air. In this particular case of sandy 0–30 cm deep topsoil from Slovakia, it was never wet enough to cause oxygen stress for plants, — in fact it never reached state of all capillary voids filled with water (FC). On the other hand, each summer the topsoil moisture dropped below the point of decreased availability (PDA), even got close to the wilting point or went through (WP), which means that during those periods plants suffered drought conditions.

Thresholds

In order to describe this behavior in more useful terms, plant ecologists and soil hydrologists came up with couple of important soil water content thresholds (Figure 1). These thresholds, also called “soil moisture ecological intervals”, define how easily plants can get the water out of the soil.

We speak about full saturation of soil when all empty spaces (pores/voids) are completely filled with water. Full saturation of the soil with water prevents air entering into the soil. Yet there is no force holding water in the soil. Roots need air as well as water so, if this situation continues, it eventually causes oxygen stress for most of the common plants because roots simply cannot breathe.

Soil also has different types of pores. Larger ones, which are called “gravitational pores”, are filled with water only when the soil is saturated and otherwise drains freely, and smaller ones called “capillary pores” which are small enough in size to prevent water from percolating down the soil profile by gravitation. These smaller pores can hold water even in well-drained soils and make it available for plants to extract. There are also even smaller pores where the water is held so tightly that plants cannot extract it.

Sandy soil

When all gravitational pores/voids are empty of water and it is present only in so called capillary pores/void we speak about the field water capacity — which is considered to be the best soil moisture status of the soil — enabling plants to retrieve the water they need, whilst leaving enough air for roots to breathe. If no new water is added into the soil, the soil dries as water is used by plants or evaporates. As soil dries less water is available to plants until the point of decreased availability when water remains only in the smallest capillary pores/voids. But this water is bound to soil particles so strongly that most plants are not able to extract it suffer from drought. Ultimately, all the available water is used up by plants, and the remaining water is inaccessible. Soil reaches the so-called wilting point and water is not available for the plants anymore. Plants permanently wilt and eventually die.

How Soil Characteristics Relate to Moisture

The tricky thing with soil moisture however is that the same amount of water (volumetric percent of the total soil column volume) can, in different soils, represent different amount of water available for plants. How big this difference could be is defined by many soil characteristics.

Loamy soil

The most important is the soil texture — a blend of all fine-earth soil mineral constituents (sand, silt, clay) and stones in various rates. In general, the finer the texture is (i.e. more clay, less sand) the more water is bound in the soil too tightly to be retrieved by plants. Even if the soil feels moist, plants can permanently wilt in clay soils. In contrast, those soils with coarse texture (i.e. more sand, less clay) can support plants with nearly all the water they can hold. Although the soil looks dry, plants can still effectively take the water out of it. The drawback here is that in coarse textured, sandy, soil nearly all water drains down the gravitational pores and therefore such a soil cannot support plants for very long time. That is also why medium textured soils (loam, silty loam, clay loam) are considered best for holding and providing the water for plants. Medium textured soils can effectively drain excess water, yet hold much water in capillary pores/voids for a long time, and still, only a relatively small amount of water remains unavailable for the plants.

A practical implication of this behavior of soil with different soil texture could be that one has to apply slightly different strategies to maintain soil moisture in the way that it can effectively supply plants with water. Sandy soils will require more frequent watering with smaller amount of water. It would not make any practical sense to try build-up a storage of water in these soils. All extra water added will simply drain out of the topsoil. Clay rich soils can absorb big amounts of water but a lot is bounded too strongly to the soil particles and thus not available for the plants. Therefore one should water even if the soil looks moist or wet — and if dry a lot of water must be added to recharge the topsoil so that it can support plants effectively. With loamy soils it is possible to be more relaxed with watering frequency, simply because one can build solid storage of water in such soils. Adding a bit more water than is necessary is perfectly fine with these soils because the water is effectively kept in the soil profile and it can be used later on.

Interested in learning more? Why not sign up for GROW Observatory’s next free online course – Citizen Research: From Data to Action – to discover how citizen-generated data on soils, food and a changing climate can create positive change in the world. Starts 5th November.

This blog was originally published on https://medium.com/grow-observatory-blog/moisture-matters-a9e33dc880a1

You must be logged in to post a comment.