Mar 29, 2019 | USA, Young Scientists

By Matt Cooper, PhD student at the Department of Geographical Sciences, University of Maryland, and 2018 winner of the IIASA Peccei Award

I never pictured myself working in Europe. I have always been an eager traveler, and I spent many years living, working and doing fieldwork in Africa and Asia before starting my PhD. I was interested in topics like international development, environmental conservation, public health, and smallholder agriculture. These interests led me to my MA research in Mali, working for an NGO in Nairobi, and to helping found a National Park in the Philippines. But Europe seemed like a remote possibility. That was at least until fall 2017, when I was looking for opportunities to get abroad and gain some research experience for the following summer. I was worried that I wouldn’t find many opportunities, because my PhD research was different from what I had previously done. Rather than interviewing farmers or measuring trees in the field myself, I was running global models using data from satellites and other projects. Since most funding for PhD students is for fieldwork, I wasn’t sure what kind of opportunities I would find. However, luckily, I heard about an interesting opportunity called the Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) at IIASA, and I decided to apply.

Participating in the YSSP turned out to be a great experience, both personally and professionally. Vienna is a wonderful city to live in, and I quickly made friends with my fellow YSSPers. Every weekend was filled with trips to the Alps or to nearby countries, and IIASA offers all sorts of activities during the week, from cultural festivals to triathlons. I also received very helpful advice and research instruction from my supervisors at IIASA, who brought a wealth of experience to my research topic. It felt very much as if I had found my kind of people among the international PhD students and academics at IIASA. Freed from the distractions of teaching, I was also able to focus 100% on my research and I conducted the largest-ever analysis of drought and child malnutrition.

© Matt Cooper

Now, I am very grateful to have another summer at IIASA coming up, thanks to the Peccei Award. I will again focus on the impact climate shocks like drought have on child health. however, I will build on last year’s research by looking at future scenarios of climate change and economic development. Will greater prosperity offset the impacts of severe droughts and flooding on children in developing countries? Or does climate change pose a hazard that will offset the global health gains of the past few decades? These are the questions that I hope to answer during the coming summer, where my research will benefit from many of the future scenarios already developed at IIASA.

I can’t think of a better research institute to conduct this kind of systemic, global research than IIASA, and I can’t picture a more enjoyable place to live for a summer than Vienna.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jan 16, 2019 | Economics, Eurasia, Russia, Systems Analysis

By Dmitry Erokhin, MSc student at Vienna University of Economics and Business (Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien) and IIASA Youth Forum participant

Dmitry Erokhin at “Connecting Europe and Asia”

On 14 December 2018, the Austrian Central Bank and the Reinventing Bretton Woods Committee co-organized a high-level conference on “Connecting Europe and Asia,” convening high-level policy makers, top business executives and renowned researchers. Taking place toward the end of the Austrian Presidency in the Council of the European Union, the goal of the event was to discuss ways to improve cooperation between Europe and Asia.

As a true Eurasianist and a member of the European Society for Eurasian Cooperation I was really interested in attending the conference.

It was opened by the governor of the Austrian Central Bank, Ewald Nowotny, who said that cooperation between Asia and Europe is vital, especially with China’s growing economic and political influence. Nowotny expressed regret that some countries see this as a challenge rather than an opportunity. Europe, however, remains the best place to be because of its economic strength.

Marc Uzan, the executive director of the Reinventing Bretton Woods Committee, noted that we live in a new age of connectivity. The economic ties between the EU and Asia are quite strong but there is still space for stronger connectivity in the form of physical and non-physical infrastructure, market integration, and maintaining stability in Central Asia. Uzan highlighted the role of the European Investment Bank in various connecting projects.

During the panel session on “Integration in Europe: European Union and Eurasia”, Elena Rovenskaya, the program director for Advanced Systems Analysis at IIASA, presented the institute as a neutral platform for depoliticized dialogue. IIASA has been running a project on the “Challenges and Opportunities of Economic Integration within a Wider European and Eurasian Space” since 2014, analyzing transport corridors, foreign direct investment, and convergence of technical product standards between EU and the Eurasian Economic Union.

This report was especially exciting for me because I had a great opportunity of participating in the International Youth Forum “Future of Eurasian and European Integration: Foresight-2040”, hosted by IIASA in December 2017, and found it interesting to see how research into Eurasian integration at IIASA has advanced since then. The concept of dividing the integration in two subgroups (bottom-up and top-down) suggested by Rovenskaya also seemed new to me.

‘Bottom-up’ integration requires coordination between participating countries and involves development of transport and infrastructure – known as the Belt and Road Initiative – including development of the Kosice-Vienna broad gauge railway extension, and the Arctic railway in Finland. The top-down scenario would be based on cooperation between regional organizations and programs such as the EU, the EAEU and the Eastern Partnership. The challenge lies in harmonizing different integration processes.

I find it unfortunate that despite the positive impact of theoretical EU-EAEU economic integration and cooperation showed by IIASA’s research, the economic relations between the EU and the EAEU are currently defined by foreign policies and not by economic reasoning.

In his address, William Tompson, the head of Eurasia Department at the Global Relations Secretariat of the OECD, highlighted that the benefits of enhanced connectivity were not automatic and that complex packages, going beyond trade and infrastructure, would be needed. I consider that Tompson raised an important point that we should not exaggerate the benefits – landlocked locations and distance to global markets can be mitigated but not eliminated. Coordination among countries to remove infrastructure and non-infrastructure bottlenecks will necessary.

Tompson’s empirics convinced me that there is a call for change. Kazakhstan pays US$250/t of freight to reach the countries with 20% of the global GDP, compared to just US$50 for Germany and the US. This is due to factors like distance, speed, and border crossings.

I was impressed by Tompson’s international freight model. It shows that logistics performance is generally poor, and competition could be enhanced. The link between policy objectives and investment choices is often unclear. Tompson also criticized the ministries of transport, which he called “ministries of road-building”, for not knowing that transport was far more than that.

The head of unit in the European Commission, Petros Sourmelis, presented the EU’s perspective. According to him, the EU is open to deeper cooperation and trade relationships with its Eastern partners, however, there are many barriers, including the EAEU’s incomplete internal market.

I consider the proposal made by Sourmelis that “one needs to start somewhere” and his hope for more engagement quite promising, but engagement at the political level is some way off. However, the EU has seen constructive steps from Russia and is open to talks to build trust.

Member of the Board of the Eurasian Economic Commission Tatyana Valovaya closed the high-level panel session. I think it was a good lead-up to start with a historical analogy of the ancient Silk Road. According to her, the global trade geography in the 21st century is shifting once again to Asia and China was likely to become a leading power within the next 20 years. I was encouraged by the idea that regional economic unions will likely lead to better global governance and building interregional partnerships between Europe, Asia and Eurasia will be vital to achieve it.

Valovaya reminded delegates that in 2003 a lot of political and technical work had been achieved towards EU-Russia cooperation, which had then been stopped for political reasons. In 2015, the EAEU began wider cooperation with China as part of the Belt and Road Initiative, and in May 2018 a non-preferential agreement was signed to harmonize technical standards and custom regulations, to decrease non-tariff barriers as much as possible and to support cooperation projects in the digital economy.

I share the view of Valovaya that the EAEU should not only consider China as a key partner. Valovaya gave the US as a good example, which has multiple economic partnership agreements. She admitted that the EAEU had some “growth pains” but stressed it is normal for such a project and efforts are focused on solving the problems.

As for me, I believe it is necessary to understand the fundamental differences for the further connectivity. Valovaya emphasized that the EAEU was not aiming to introduce a common currency or to create a political union like the EU. EU-EAEU cooperation will strengthen both unions. More technical cooperation will be needed. And, of course, the leaders of the EU should be participating in the dialogue to better understand the EAEU and its work towards more connectivity in Eurasia.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jun 4, 2018 | Economics, Eurasia

By Michael Emerson, Associate Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for European Policy Studies, and Senior Research Scholar at IIASA

Any substantive common economic space from ‘Lisbon to Vladivostok’ would require the reduction or elimination of tariffs and key non-tariff barriers (such as technical product standards) within a wide-ranging free trade agreement (FTA). For the EU this seems to be an advantageous proposition from an economic standpoint. However, one would expect the pre-conditions posed by the EU for the opening of negotiations to be several and stringent, particularly in terms of political progress over the Ukraine conflict, Belarus’ membership of the World Trade Organization (WTO), and better compliance with WTO rules, with a reduction in protectionist policies in Russia especially.

© Rawpixel.com | Shutterstock

The issue of tariffs is of high political and economic significance, but still a conceptually simple matter. By contrast, the removal of non-tariff barriers is immensely complex, involving dozens or hundreds of regulations and thousands of product standards. We therefore examined the non-tariff issue in some detail [1].

Surprising as it may seem, the harmonization of product standards has actually already progressed as a result of the autonomous policy of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and its member states to adopt increasingly international and European standards. Around 30 sector-specific framework regulations have been adopted by the EAEU, based on EU directives, and backed up by some 5,830 product-specific standards, which are identical to those of the EU (to a large degree EU standards are identical to those of the International Standards Organization).

Therefore, at least for industrial products, there is already a promising basis for an agreement between the EU and EAEU. An important further step could be a mutual recognition agreement (MRA) for conformity assessment. This would mean that each party’s accredited standards agencies would be empowered to certify the conformity of their exporters’ products with standards required by the importing state, without further testing or certification in the importing country. An MRA would thus significantly reduce the cost of non-tariff barriers. An example of this type of agreement is the one between the EU and the US that has been functioning effectively without the scrapping of tariffs in an FTA.

It would also in principle not only be possible, but more plausible to establish a stand-alone MRA between the EU and the EAEU earlier than as part of a wider ranging free trade agreement that also scraps tariffs. This is because under the rules of the WTO, member states cannot enter into a free trade agreement with non-member states. This specifically concerns the situation of Belarus as the only non-WTO member state of the EAEU. However, this limitation under WTO rules does not apply to MRAs of the type mentioned.

An MRA could of course also be incorporated into a more ambitious FTA that scraps tariffs. There is however also the fundamental question of whether the EAEU and its member states would consider this to be in their interests.

So far, this has been very unclear. In Russia, one hears the argument that an FTA with the EU would be too imbalanced in favor of the EU. Indeed, most Russian exports to the EU, such as oil and gas, are already being traded without tariffs. It should be noted that the EAEU is currently negotiating a ‘non-preferential’ agreement with China, which means that tariffs would not be eliminated. While the slogan ‘Lisbon to Vladivostok’ has featured in many speeches, there is much more caution on both sides when the practicalities of a FTA are considered.

It would still be possible for an FTA between the EU and EAEU to be sensitive to the concerns of the EAEU by being ‘asymmetrical’–meaning that while the EU could scrap its tariffs immediately, the EAEU might do this over a transition period of several years. An example of this is the EU’s deep and comprehensive free trade agreement (DCFTA) with Ukraine, which sees some of the most sensitive sectors getting transitional delays of up to ten years.

These scenarios cannot go ahead for the time being for the reasons already stated above. However, the main point is that there are well-specified concepts available for a possible agreement to scrap tariffs and non-tariff barriers between the two parties. For the EU this would be attractive as an economic proposition. Whether this could see consensus among EAEU member states is however not so clear. A very narrow cooperation agreement that does not include free trade would be of limited interest to the EU.

References

[1] Emerson M & Kofner J (2018). Technical Product Standards and Regulations in the EU and EAEU – Comparisons and Scope for Convergence. IIASA Report. Laxenburg, Austria

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Three IIASA papers on “Challenges and Opportunities of Economic Integration within a Wider European and Eurasian Space” will be presented in Moscow at the high-level conference “Prospects for a deeper EU – EAEU economic cooperation and perspectives for business” on 6 June. See event page.

May 30, 2018 | Economics, Food & Water, Sustainable Development, Systems Analysis

By Alan Nicol, Strategic Program Leader at the International Water Management Institute (IWMI)

I was at the local corner store in Uganda last week and noticed the profusion of rice being sold, the origin of which was from either India or Pakistan. It is highly likely that this rice being consumed in Eastern Africa, was produced in the Indus Basin, using Indus waters, and was then processed and shipped to Africa. That is not exceptional in its own right and is, arguably, a sign of a healthy global trading system.

Nevertheless, the rice in question is likely from a system under increasing stress, one that is often simply viewed as a hydrological (i.e., basin) unit. What my trip to the corner store shows is that perhaps more than ever before a system such as the Indus is no longer confined–it extends well beyond its physical (hydrological) borders.

Not only does this rice represent embedded ‘virtual’ water (the water used to grow and refine the produce), but it also represents policy decisions, embedded labor value, and the gamut of economic agreements between distribution companies and import entities, as well as the political relationship between East Africa and South Asia. On top of that are the global prices for commodities and international market forces.

In that sense, the Indus River Basin is the epitome of a complex system in which simple, linear causality may not be a useful way for decision makers to determine what to do and how to invest in managing the system into the future. Integral to this biophysical system, are social, economic, and political systems in which elements of climate, population growth and movement, and political uncertainty make decisions hard to get right.

Like other systems, it is constantly changing and endlessly complex, representing a great deal of interconnectivity. This poses questions about stability, sustainability, and hard choices and trade-offs that need to be made, not least in terms of the social and economic cost-benefit of huge rice production and export.

An aerial view of the Indus River valley in the Karakorum mountain range of the Basin. © khlongwangchao | Shutterstock

So how do we go about planning in a system that is in such constant flux?

Coping with system complexity in the Indus is the overarching theme of the third Indus Basin Knowledge Forum (IBKF) being co-hosted this week by the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), and the World Bank. Titled Managing Systems Under Stress: Science for Solutions in the Indus Basin, the Forum brings together researchers and other knowledge producers to interface with knowledge users like policymakers to work together to develop the future direction for the basin, while improving the science-decision-making relationship. Participants from four riparian countries–Afghanistan, China, India, and Pakistan–as well as from international organizations that conduct interdisciplinary research on factors that impact the basin, will work through a ‘marketplace’ for ideas, funding sources, and potential applications. The aim is to narrow down a set of practical and useful activities with defined outcomes that can be tracked and traced in coming years under the auspices of future fora.

The meeting builds on the work already done and, crucially, on relations already established in this complex geopolitical space, including under the Indus Forum and the Upper Indus Basin Network. By sharing knowledge, asking tough questions, and identifying opportunities for working together, the IBKF hopes to pin down concrete commitments from both funders and policymakers, but also from researchers, to ensure high quality outputs that are of real, practical relevance to this system under stress–from within and externally.

Scenario planning

Feeding into the IBKF3, and directly preceding the forum, the Integrated Solutions for Water, Energy, and Land Project (ISWEL) will bring together policymakers and other stakeholders from the basin to explore a policy tool that looks at how best to model basin futures. This approach will help the group conceive possible futures and model the pathways leading to the best possible outcomes for the most people. This ‘policy exercise approach’ will involve six steps to identify and evaluate possible future pathways:

- Specifying a ‘business as usual’ pathway

- Setting desirable goals (for sustainability pathways)

- Identifying challenges and trade-offs

- Understanding power relations, underlying interests, and their role in nexus policy development

- Developing and selecting nexus solutions

- Identifying synergies, and

- Building pathways with key milestones for future investments and implementation of solutions.

The summary of this scenario development workshop and a vision for the Indus Basin will be shared as part of the IBKF3 at the end of the event, and will help the participants collectively consider what actions can be taken to ensure a prosperous, sustainable, and equitable future for those living in the basin.

The rice that helps feed parts of East Africa plays a key global role–the challenge will be ensuring that this important trading relationship is not jeopardized by a system that moves from pressure points to eventual collapse. Open science-policy and decision-making collaboration are key to making sure that this does not happen.

This blog was originally published on https://wle.cgiar.org/thrive/2018/05/29/rice-and-reason-planning-system-complexity-indus-basin.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 28, 2018 | Air Pollution, Climate, Climate Change, Ecosystems, Energy & Climate, Women in Science

By Beatriz Mayor, Research Scholar at IIASA

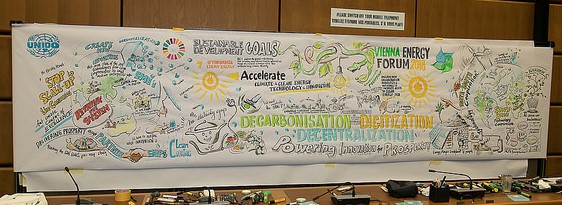

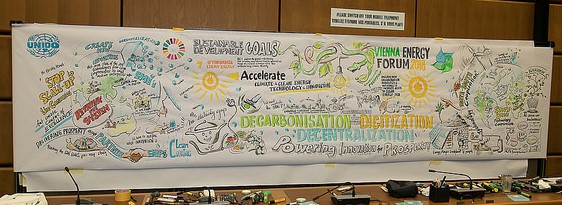

On 14 and 15 May, Vienna hosted two important events within the frame of the world energy and climate change agendas: the Vienna Energy Forum and the R20 Austrian World Summit. Since I had the pleasure and privilege to attend both, I would like to share some insights and relevant messages I took home with me.

Beatriz Mayor at the Austrian World Summit © Beatriz Mayor

To begin with, ‘renewable energy’ was the buzzword of the moment. Renewable energy is not only the future, it is the present. Recently, 20-year solar PV contracts were signed for US$0.02/kWh. However, renewable energy is not only about mitigating the effects of climate change, but also about turning the planet into a world we (humans from all regions, regardless of the local conditions) want to live in. It is not only about producing energy, about reaching a number of KWh equivalent to the expected demand–renewables are about providing a service to communities, meeting their needs, and improving their ways of life. It does not consist only of taking a solar LED lamp to a remote rural house in India or Africa. It is about first understanding the problem and then seeking the right solution. Such a light will be of no use if a mother has to spend the whole day walking 10 km to find water at the closest spring or well, and come back by sunset to work on her loom, only to find that the lamp has run out of battery. Why? Because her son had to take it to school to light his way back home.

This is where the concept of ‘nexus’ entered the room, and I have to say that more than once it was brought up by IIASA Deputy Director General Nebojsa Nakicenovic. A nexus approach means adopting an integrated approach and understanding both the problems and the solutions, the cross and rebound effects, and the synergies; and it is on the latter that we should focus our efforts to maximize the effect with minimal effort. Looking at the nexus involves addressing the interdependencies between the water, energy, and food sectors, but also expanding the reach to other critical dimensions such as health, poverty, education, and gender. Overall, this means pursuing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Vienna Energy Forum banner created by artists on the day © UNIDO / Flickr

Another key word that was repeatedly mentioned was finance. The question was how to raise and mobilize funds for the implementation of the required solutions and initiatives. The answer: blended funding and private funding mobilization. This means combining different funding sources, including crowd funding and citizen-social funding initiatives, and engaging the private sector by reducing the risk for investors. A wonderful example was presented by the city of Vienna, where a solar power plant was completely funded (and thus owned) by Viennese citizens through the purchase of shares.

This connects with the last message: the importance of a bottom-up approach and the critical role of those at the local level. Speakers and panelists gave several examples of successful initiatives in Mali, India, Vienna, and California. Most of the debates focused on how to search for solutions and facilitate access to funding and implementation in the Global South. However, two things became clear. Firstly, massive political and investment efforts are required in emerging countries to set up the infrastructural and social environment (including capacity building) to achieve the SDGs. Secondly, the effort and cost of dismantling a well-rooted technological and infrastructural system once put in place, such as fossil fuel-based power networks in the case of developed countries, are also huge. Hence, the importance of emerging economies going directly for sustainable solutions, which will pay off in the future in all possible aspects. HRH Princess Abze Djigma from Burkina Faso emphasized that this is already happening in Africa. Progress is being made at a critical rate, triggered by local initiatives that will displace the age of huge, donor-funded, top-down projects, to give way to bottom-up, collaborative co-funding and co-development.

Overall, if I had to pick just one message among the information overload I faced over these two days, it would be the statement by a young fellow in the audience from African Champions: “Africa is not underdeveloped, it is waiting and watching not to repeat the mistakes made by the rest of the world.” We should keep this message in mind.

You must be logged in to post a comment.