Jul 1, 2021 | Biodiversity, Climate Change, Ecosystems

By Florian Hofhansl, researcher in the Biodiversity, Ecology, and Conservation Research Group of the IIASA Biodiversity and Natural Resources Program

Florian Hofhansl writes about a successful paper on which he was the lead author that was recently ranked #32 on the list of the Top 100 most downloaded ecology papers published in 2020.

Early in 2020, one of my manuscripts titled “Climatic and edaphic controls over tropical forest diversity and vegetation carbon storage” was accepted for publication in the prestigious journal Nature Scientific Reports.

Initially, I was worried about the bad timing when I was informed that the paper would be published on 19 March – right at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic – since it took me and my colleagues almost a decade to collect the data and publish our results on the biodiversity and functioning of tropical forest ecosystems.

However, my worries completely disappeared when I learned that our research article had received more that 3,000 downloads, placing it among the top 100 downloaded ecology papers for Scientific Reports in 2020. This is an extraordinary achievement considering that Scientific Reports published more than 500 ecology papers in 2020. Seeing our paper positioned at #32 of the top 100 most downloaded articles in the field, therefore meant that our science was of real value to the research community.

However, my worries completely disappeared when I learned that our research article had received more that 3,000 downloads, placing it among the top 100 downloaded ecology papers for Scientific Reports in 2020. This is an extraordinary achievement considering that Scientific Reports published more than 500 ecology papers in 2020. Seeing our paper positioned at #32 of the top 100 most downloaded articles in the field, therefore meant that our science was of real value to the research community.

We kicked off our study in the dry-season of 2011 by selecting twenty one-hectare forest inventory plots at the beautiful Osa peninsula – one of the last remnants of continuous primary forest – located in southwestern Costa Rica. We did not expect that our project would receive this much scientific recognition as we were merely interested in describing the stunning biodiversity of this remote tropical region. Nevertheless, we were striving to understand the functioning of the area’s megadiverse ecosystem by conducting repeated measurements of forest characteristics, such as forest growth, tree mortality, and plant species composition.

After periodically revisiting the permanent inventory plots, and recording data for almost a decade, we found stark differences in the composition of tropical plant species such as trees, palms, and lianas across the landscape. Most interestingly, these different functional groups follow different strategies in their competition for light and nutrients, both limiting plant growth in the understory of a tropical rainforest. For instance, lianas – which are long-stemmed, woody vines – are relatively fast growing and try to reach the canopy to get to the sunlight, but they do not store as much carbon as a tree stem to reach the same height in the canopy. In contrast, palms share a different strategy and mostly stay in the lower sections of the forest where they collect water and nutrients with their bundles of palm leaves arranged upward to catch droplets and nutrients falling from above, thus reducing local resource limitation.

Lead author Florian Hofhansl and field botanist, Eduardo Chacon-Madrigal got stuck between roots of the walking palm (Socratea exorrhiza), while surveying one of the twenty one-hectare permanent inventory plots © Florian Hofhansl

Our results indicate that each plant functional group – that is, a collection of organisms (i.e., trees, palms, or lianas) that share the same characteristics – was associated with specific climate conditions and distinct soil properties across the landscape. Hence, this finding indicates that we would have to account for the small-scale heterogeneity of the landscape in order to understand future ecosystem responses to projected climate change, and thus to accurately predict associated tropical ecosystem services under future scenarios.

Our study and its subsequent uptake by the research community, illustrates the value of conducting on-site experiments that empower researchers to understand crucial ecosystem processes and applying these results in next-generation models. Research like this makes it possible for scientists to evaluate vegetation–atmosphere feedbacks and thus determine how much of man-made emissions will remain in the atmosphere and therefore might further heat up the climate system in the future.

Our multidisciplinary research project furthermore highlighted that it is crucial to gather knowledge from multiple disciplines, such as botany (identifying species), plant ecology (identifying functional strategies), and geology (identifying differences in parent material and soil types) – since all of these factors need to be considered in concert to capture the complexity of any given system, when aiming to understand the systematic response to climate change.

Read more about the research here: https://tropicalbio.me/blog

Reference:

Hofhansl F, Chacón-Madrigal E, Fuchslueger L, Jenking D, Morera A, Plutzar C, Silla F, Andersen K, et al. (2020). Climatic and edaphic controls over tropical forest diversity and vegetation carbon storage. Scientific Reports DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-61868-5 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/16360]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Sep 15, 2020 | Biodiversity, Ecosystems, Environment

IIASA researchers Michael Obersteiner, David Leclère, and Piero Visconti discuss the findings of their latest paper, which proposes pathways to reverse the current trend of biodiversity loss and shows that the next 30 years will be pivotal for the Earth’s wildlife.

Species are going extinct at an unprecedented rate. Wildlife populations have fallen by more than two-thirds over the last 50 years, according to a new report from the World Wildlife Fund. The sharpest declines have occurred throughout the world’s rivers and lakes, where freshwater wildlife has plummeted by 84% since 1970 – about 4% per year.

But why should we care? Because the health of nature is intimately linked to the health of humans. The emergence of new infectious diseases like COVID-19 tend to be related to the destruction of forests and wilderness. Healthy ecosystems are the foundation of today’s global economies and societies, and the ones we aspire to build. As more and more species are drawn towards extinction, the very life support systems on which civilization depends are eroded.

Even for hard-nosed observers like the World Economic Forum, biodiversity loss is a disturbing threat with few parallels. Of the nine greatest threats to the world ranked by the organization, six relate to the ongoing destruction of nature.

© Chris Van Lennep | Dreamstime.com

Economic systems and lifestyles which take the world’s generous stocks of natural resources for granted will need to be abandoned, but resisting the catastrophic declines of wildlife that have occurred over the last few decades might seem hopeless. For the first time, we’ve completed a science-based assessment to figure out how to slow and even reverse these trends.

Our new paper in Nature featured the work of 60 coauthors and built on efforts steered by the Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. We considered ambitious targets for rescuing global biodiversity trends and produced pathways for the international community to follow that could allow us to meet these goals.

Bending the curve

The targets of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity call for global trends of terrestrial wildlife to stop declining and start recovering by 2050 or earlier. Changes in how land is used – from pristine forest to cropland or pasture – rank among the greatest threats to biodiversity on land worldwide. So what are the necessary conditions for biodiversity to recover during the 21st century while still supporting growing and affluent human societies?

Two key areas of action stand out from the rest. First, there must be renewed ambition from the world’s governments to establish large-scale conservation areas, placed in the most valuable hotspots for biodiversity worldwide, such as small islands with species found nowhere else. These reserves, in which wildlife will live and roam freely, will need to cover at least 40% of the world’s land surface to help bend the curve from decline to recovery for species and entire ecosystems.

The location of these areas, and how well they are managed, is often more important than how big they are. Habitat restoration and conservation efforts need to be targeted where they are needed most – for species and habitats on the verge of extinction.

The next 30 years will prove pivotal for Earth’s biodiversity. Leclère et al. (2020) © IIASA

Second, we must transform our food systems to produce more on less land. If every farmer on Earth used the best available farming practices, only half of the total area of cropland would be needed to feed the world. There are lots of other inefficiencies that could be ironed out too, by reducing the amount of waste produced during transport and food processing, for example. Society at large can help in this effort by shifting towards healthier and more sustainable diets, and reducing food waste.

This should happen alongside efforts to restore degraded land, such as farmland that’s becoming unproductive as a result of soil erosion, and land that’s no longer needed as agriculture becomes more efficient and diets shift. This could return 8% of the world’s land to nature by 2050. It will be necessary to plan how the remaining land is used, to balance food production and other uses with the conservation of wild spaces.

Without a similar level of ambition for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, climate change will ensure the world’s wildlife fares badly this century. Only a comprehensive set of policy measures that transform our relationship with the land and rapidly scale down pollution can build the necessary momentum. Our report concludes that transformative changes in our food systems and how we plan and use land will have the biggest benefits for biodiversity.

But the benefits wouldn’t end there. While giving back to nature, these measures would simultaneously slow climate change, reduce pressure on water, limit nitrogen pollution in the world’s waterways and boost human health. When the world works together to halt and eventually reverse biodiversity loss, it’s not only wildlife that will thrive.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation. Read the original article here.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 5, 2020 | Biodiversity, Data and Methods, Ecosystems, Young Scientists

By Martin Jung, postdoctoral research scholar in the IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program.

IIASA postdoc Martin Jung discusses how a newly developed map can help provide a detailed view of important species habitats, contribute to ongoing ecosystem threat assessments, and assist in biodiversity modeling efforts.

Biodiversity is not evenly distributed across our planet. To determine which areas potentially harbor the greatest number of species, we need to understand how habitats valuable to species are distributed globally. In our new study, published in Nature Scientific Data, we mapped the distribution of habitats globally. The habitats we used are based on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List habitat classification scheme, one of the most widely used systems to assign species to habitats and assess their extinction risk. The latest map (2015) is openly available for download here. We also built an online viewer using the Google Earth Engine platform where the map can be visually explored and interacted with by simply clicking on the map to find out which class of habitat has been mapped in a particular location.

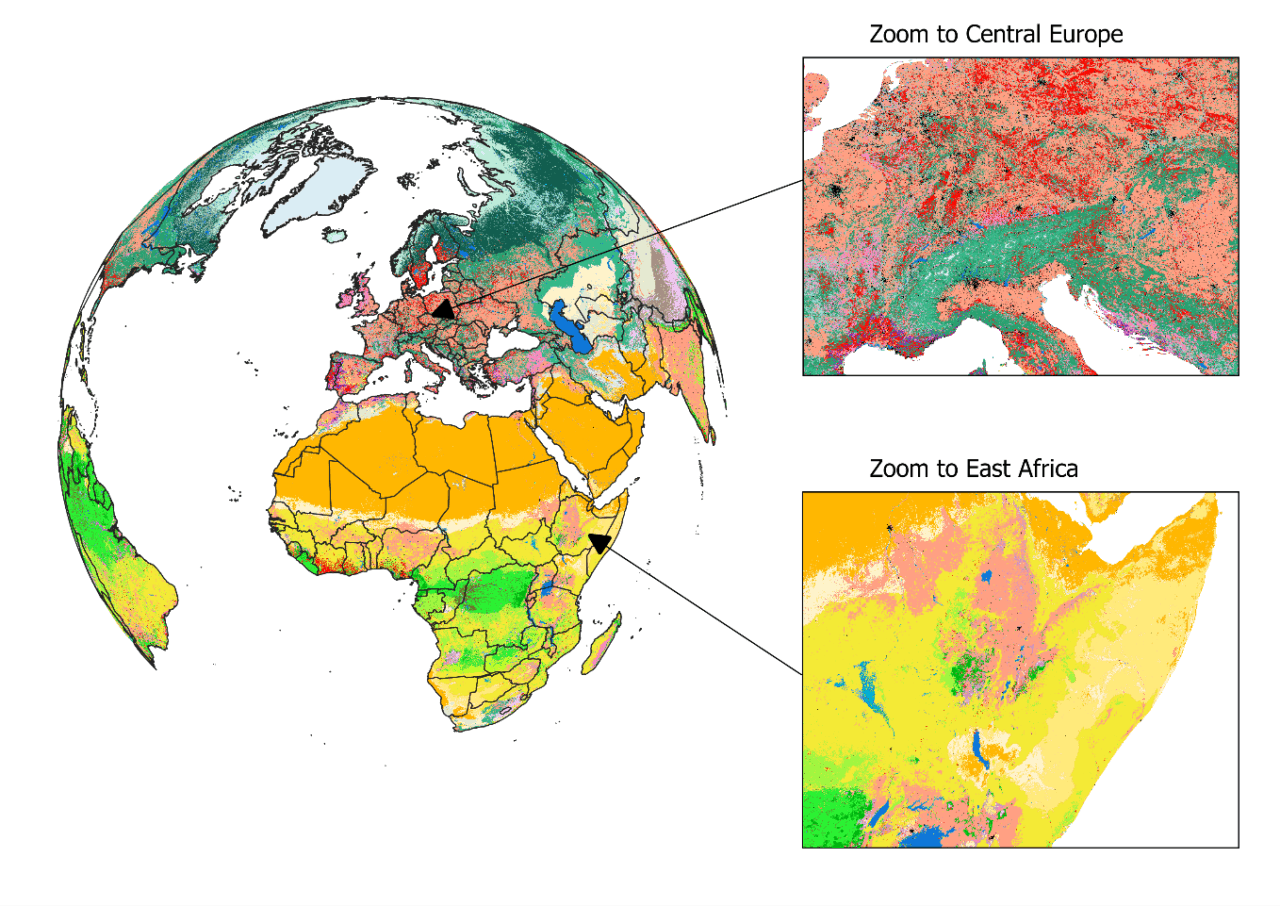

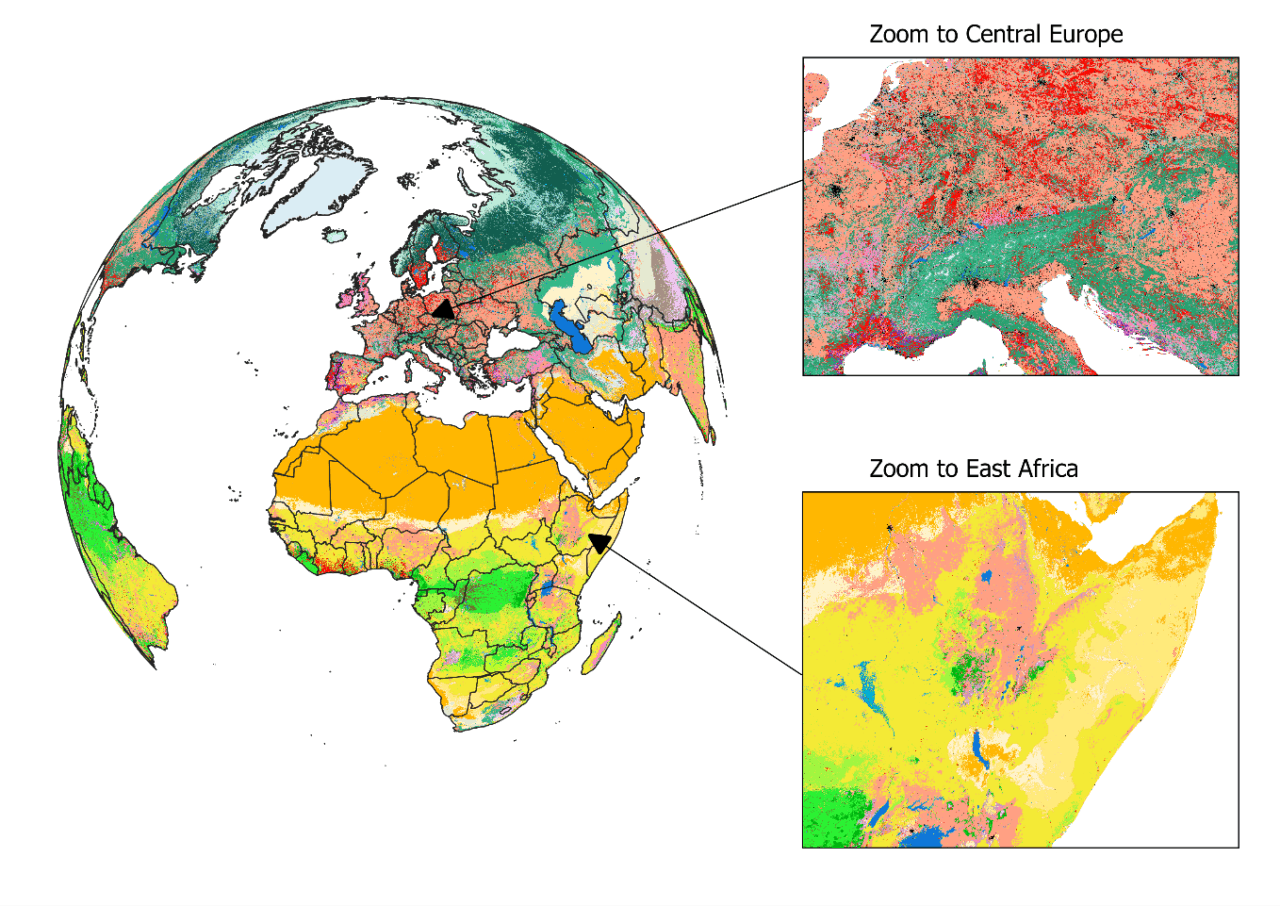

Figure 1: View on the habitat map with focus on Europe and Africa. For a global view and description of the current classes mapped, please read Jung et al. 2020 or have a look at the online interactive interface.

The habitat map was created as an intersection of various, best-available layers on land cover, climate, and land use (Figure 1). Specifically, we created a decision tree that determines for each area on the globe the likely presence of one of currently 47 mapped habitats. For example, by combining data on tropical climate zones, mountain regions and forest cover, we were able to estimate the distribution of subtropical/tropical moist mountainous rain forests, one of the most biodiverse ecosystems. The habitat map also considers best available land use data to map human modified or artificial habitats such as rural gardens or urban sites. Notably, and as a first, our map also integrates upcoming new data on the global distribution of plantation forests.

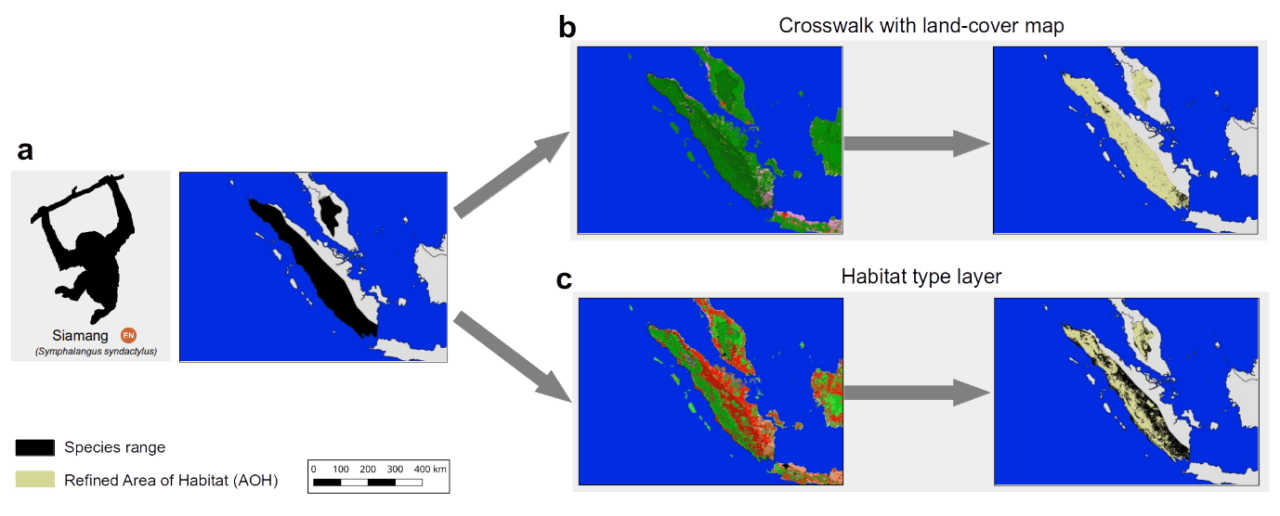

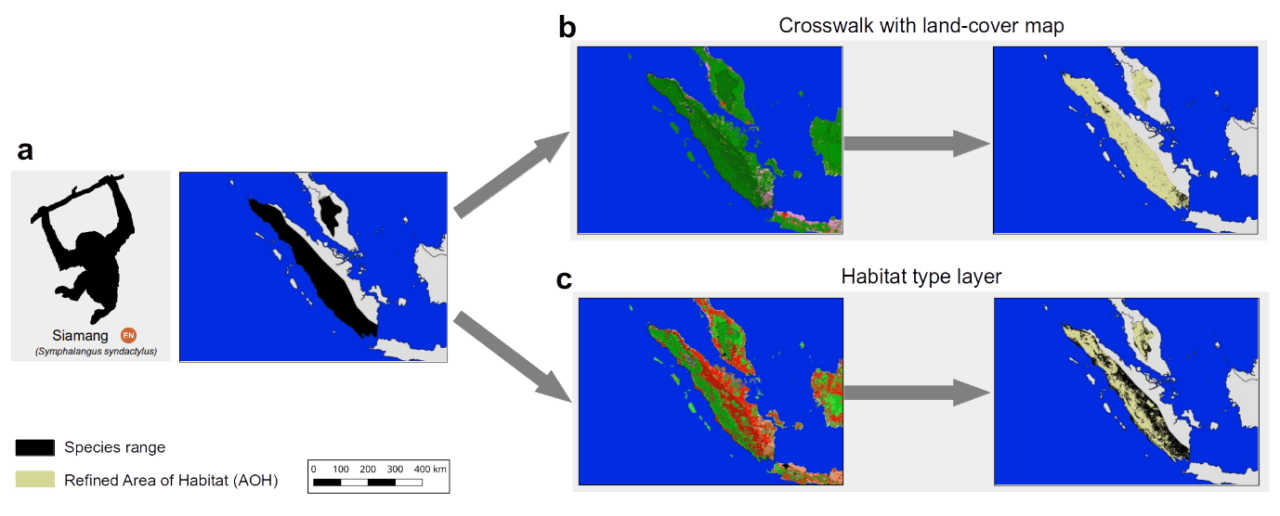

What makes this map so useful for biodiversity assessments? It can provide a detailed view on the remaining coverage of important species habitats, contribute to ongoing ecosystem threat assessments, and assist in global and national biodiversity modeling efforts. Since the thematic legend of the map – in other words the colors, symbols, and styles used in the map – follows the same system as that used by the IUCN for assessing species extinction risk, we can easily refine known distributions of species (Figure 2). Up to now, such refinements were based on crosswalks between land cover products (Figure 2b), but with the additional data integrated into the habitat map, such refinements can be much more precise (Figure 2c). We have for instance conducted such range refinements as part of the Nature Map project, which ultimately helped to identify global priority areas of importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Figure 2: The range of the endangered Siamang (Symphalangus syndactylus) in Indonesia and Malaysia according to the IUCN Red List. Up to now refinements of its range were conducted based on land cover crosswalks (b), while the habitat map allows a more complete refinement (c).

Similar as with other global maps, this new map is certainly not without errors. Even though a validation has proved good accuracy at high resolution for many classes, we stress that – given the global extent and uncertainty – there are likely fine-scale errors that propagate from some of the input data. Some, such as the global distribution of pastures, are currently clearly insufficient, with existing global products being either outdated or not highly resolved enough to be useful. Luckily, with the decision tree being implemented on Google Earth Engine, a new version of the map can be created within just two hours.

In the future, we plan to further update the habitat map and ruleset as improved or newer data becomes available. For instance, the underlying land cover data from the European Copernicus Program is currently only available for 2015, however, new annual versions up to 2018 are already being produced. Incorporating these new data would allow us to create time series of the distribution of habitats. There are also already plans to map currently missing classes such as the IUCN marine habitats – think for example of the distribution of coral reefs or deep-sea volcanoes – as well as improving the mapped wetland classes.

Lastly, if you, dear reader, want to update the ruleset or create your own habitat type map, then this is also possible. All input data, the ruleset and code to fully reproduce the map in Google Earth Engine is publicly available. Currently the map is at version 003, but we have no doubt that the ruleset and map can continue to be improved in the future and form a truly living map.

Reference:

Jung M, Raj Dahal P, Butchart SHM, Donald PF, De Lamo X, Lesiv M, Kapos V,Rondinini C, & Visconti P (2020). A global map of terrestrial habitat types. Nature Scientific Data DOI: 10.1038/s41597-020-00599-8

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Dec 5, 2016 | Climate Change, Environment, Sustainable Development

By Alvaro Silva Iribarrem, researcher in the IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management Program.

Restoration of degraded ecosystems is an exciting and relatively new way of looking into the conservation of natural capital—the world’s natural assets, including soil, air, water, and all living things. For one, the success of restoration is more readily verifiable than, for example, avoided degradation. Further, it increases the landscape’s resilience: natural areas can be placed around agricultural crops, increasing their yields by providing habitat for pollinators and therefore increasing pollination, protecting them from natural disasters, and improving the provision of important ecosystem services for human wellbeing.

These services include removing CO2 from the atmosphere (which contributes directly to climate change mitigation); ensuring that more sediment is filtered from the rivers (which reduces the risk of landslides and floods); and providing habitat for a large diversity of species. For scientists, it feels like being at the head of the counter-offensive: it is us, humans, finally doing something not only to slow our seemingly unstoppable degradation of the environment, but to actively start pushing it back.

Restoring an ecosystem to its original state can be an expensive endeavor, but tropical rainforests are very resilient. For example, even after centuries of extensive use of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest, which has been reduced to a tenth of its size, in many places it would still grow back to much of its original state in a manner of decades, if allowed to do so. For such ecosystems, natural regeneration represents an extraordinary opportunity to enable restoration at scales that would otherwise be cost-prohibitive.

In places like the Paraitinga watershed, in the countryside of São Paulo state, most of the original forest has long been cleared, and replaced, predominantly, by small dairy farms. After over a century of careless land use, large areas of the converted landscape has degraded to the point where yields are so low that farms are barely viable. The lack of forest cover has led to frequent floods. The worst of the recent ones, in 2010, destroyed most of the historical city of São Luiz do Paraitinga, with a population of 11 thousand inhabitants.

The aftermath of the 2010 flood in Paraitinga. © Luciano Dinamarco

In a couple of recent publications, we made a comprehensive effort to include the natural regeneration of that watershed’s native forest as part of a bigger plan for more sustainable development of the region, one that would increase its resilience to this kind of disaster.

Starting from a landscape approach, we looked at the potential for grass growth in the region, and concluded that it was possible to accommodate all foreseeable future demands for cattle production and still make space for the restoration of a large area in the watershed. Sustainable intensification of current pasture is key to avoid the economic losses that could otherwise follow the land shortage caused by such a large-scale restoration. It would also help to gain the farmers’ acceptance. By producing more in a smaller area, they could let go of the degraded areas they currently use, allowing the native forest fragments nearby to spread.

In our regeneration scenario, we assume that around 24,000 hectares of pastureland that is presently abandoned in the watershed will be allowed to undergo natural regeneration in the next 20 years. This naturally occurring forest regrowth would sequester 6.2 million tons of CO2 from the atmosphere. Additionally, it would reduce sediment load into rivers by 570,000 tons annually, bringing water purification costs in the area down by 0.37 dollars per year per hectare restored. Finally we showed that restoration of even this relatively small area would be enough to significantly increase habitat availability for all species, particularly for those which travel between forest fragments.

To understand the difficulties farmers face in improving productivity, we conducted interviews and focus groups with them. We found that the tendency to keep to their old, low-producing, land-extensive ways, is less related to a resistance to change, and more to a lack of technical knowledge and the means to make the upfront investments needed to switch to a more productive system. Credit for investment is available and cheap in the country, but only a small number of farmers in the region risk taking it. Technical assistance is key to tap into these resources and enable the necessary improvement of the watershed’s production. The conditions for unlocking large-scale forest regrowth, not only in the Paraitinga watershed but in many similar landscapes in the country, are in place—they need only to be implemented properly.

Strassburg BB, Barros FS, Crouzeilles R, Silva Iribarrem, A, dos Santos JS, Silva D, Sansevero JB, Alves-Pinto H, Feltrain-Barbieri R, & Latawiec AE (2016). The role of natural regeneration to ecosystem services provision and habitat availability: a case study in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Biotropics.

Alves-Pinto HN, Latawiec AE, Strassburg BBN, Barros FSM, Sansevero JBB, Iribarrem A, Crouzeilles R, Lemgruber LC, Rangel M, & Silva ACP (2016). Reconciling rural development and ecological restoration: Strategies and policy recommendations for the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Land Use Policy.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 29, 2013 | Energy & Climate, Science and Policy

This post was originally published on the recharge.green blog. IIASA is a partner in the new project, which focuses on the potential for renewable energy in the Alps.

When I think of an alpine forest, I think of the towering cedar trees that blanket the Cascade mountains near my native Seattle, with trunks so broad you can’t reach your arms around them. I think of the shadowy quiet that envelops me as I wander through a mountain forest in my new home in Austria. I think of the scent of pine needles and the bounce of my feet on a trail softened by forest litter. The value of a mature forest to people like me who love the outdoors—its recreational value—is impossible to put into numbers.

When I think of an alpine forest, I think of the towering cedar trees that blanket the Cascade mountains near my native Seattle, with trunks so broad you can’t reach your arms around them. I think of the shadowy quiet that envelops me as I wander through a mountain forest in my new home in Austria. I think of the scent of pine needles and the bounce of my feet on a trail softened by forest litter. The value of a mature forest to people like me who love the outdoors—its recreational value—is impossible to put into numbers.

We can, however, calculate the effects of different styles of forest management on more quantifiable criteria. We can determine how much carbon dioxide is taken up from the atmosphere and stored by long-growing forests. And we can estimate how much bioenergy we can sustainably produce by managing forests for biomass harvesting.

This is exactly what IIASA scientists have done for their first efforts in the recharge.green project. IIASA’s role in the project is to use our modeling expertise to explore the various possibilities for renewable energy expansion in the Alps. We are also looking at the tradeoffs and benefits of the different possible scenarios and ecosystem services (ESS). As a first step, researchers Florian Kraxner, Sylvain Leduc , Sabine Fuss (now with MCC Berlin), Nicklas Forsell, and Georg Kindermann used the IIASA BeWhere and Global Forest (G4M) models look at the tradeoffs between bioenergy production or carbon storage in alpine forests.

These graphs show the first results for recharge.green from IIASA’s BeWhere and G4M models, optimizing the location of bioenergy plants to maximize either carbon sequestration (top) or bioenergy production (bottom). The gradiant of green colors shows the amount of carbon storage over the landscape, while the red boxes (and according gradient in red) show the harvesting intensity in different harvesting areas.

“Managing forests optimally for bioenergy requires more intensive management,” says Kraxner. That means shorter rotations where trees are cut more often. Such a forest is made up of smaller trees that may look more like “close-to-nature plantations” than an old-growth forest. In contrast, managing forests for carbon storage means letting the trees grow older, also good for biodiversity and environmental preservation.

In their analysis, Kraxner and the team compared two management strategies: restricting bioenergy production to a small land area, and managing it intensively, or spreading bioenergy over a large land area but managing less intensively over the whole area. They found that the same amount of bioenergy could be produced by managing a small amount of land area intensively for bioenergy production. This more intensive management on a small area of land would free up a larger land area for preservation and protection or other special dedication to ecosystem services.

“Both methods are sustainable,” says Kraxner, “but the optics are different. Intensification can be a good solution to provide renewable energy and at the same time preserve biodiversity and the more intangible values of mature forests.”

What do you think? What should our priorities be in managing Alpine forests?

However, my worries completely disappeared when I learned that our research article had received more that 3,000 downloads, placing it among the top 100 downloaded ecology papers for Scientific Reports in 2020. This is an extraordinary achievement considering that Scientific Reports published more than 500 ecology papers in 2020. Seeing our paper positioned at #32 of the top 100 most downloaded articles in the field, therefore meant that our science was of real value to the research community.

However, my worries completely disappeared when I learned that our research article had received more that 3,000 downloads, placing it among the top 100 downloaded ecology papers for Scientific Reports in 2020. This is an extraordinary achievement considering that Scientific Reports published more than 500 ecology papers in 2020. Seeing our paper positioned at #32 of the top 100 most downloaded articles in the field, therefore meant that our science was of real value to the research community.

You must be logged in to post a comment.