Nov 20, 2020 | Climate Change, Risk and resilience, Young Scientists

By Greg Davies-Jones, 2020 IIASA Science Communication Fellow

Greg Davies-Jones sits down with 2020 IIASA Young Scientists Summer Program (YSSP) participant Lisa Thalheimer to discuss how attribution science can play a leading role in addressing disaster displacement.

We live in the era of the greatest human movement in recorded history – there are more people on the move today than at any other point in our past. Despite the common misconception that most migrants cross borders, a lot of migration actually occurs internally. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center, a staggering 72% of internal migration is linked to displacement due to natural hazards or extreme weather.

Pinpointing the finer details of how human mobility might evolve remains a complex undertaking. Contemporary migratory movements reflect the complex patterns of social and economic globalization – they flow in all directions and affect all countries in one way or another. It is clear that given the rising global average temperatures, natural hazards and extreme weather events will increase in frequency, intensity, and duration, adversely effecting many parts of the globe. A better understanding of how human-induced climate change influences disaster displacement will undoubtedly be essential in addressing future human mobility and informing the debate on climate and migration policies.

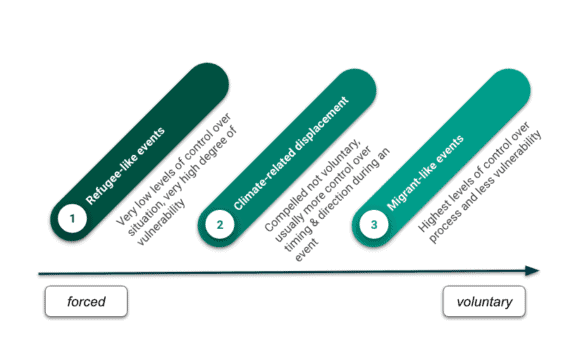

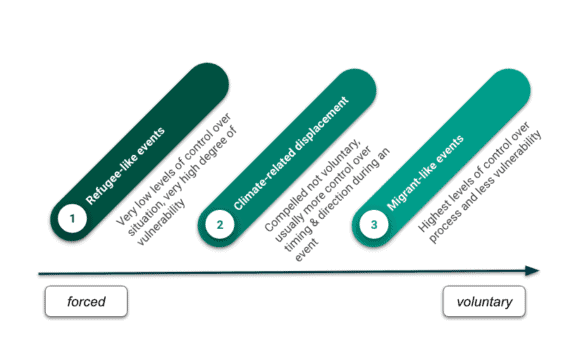

Figure: Climate-related displacement on an axis of forced to voluntary human mobility. Thalheimer (2020)

The focus of 2020 YSSP participant Lisa Thalheimer’s research is on internal displacement in East Africa, in particular, Somalia. As part of her YSSP project, Thalheimer hopes to determine whether, and to what extent, human-induced climate change altered the likelihood of extreme weather-related displacement in Somalia by conflating econometric methods and Probabilistic Event Attribution (PEA).

“Econometrics is essentially the application of statistical methods to quantify impacts and PEA is a way of examining to what extent extreme weather events can be linked with past man-made emissions. By combining the two methods we hope to quantify the ramifications of extreme weather and displacement in East Africa,” she explains.

This is no mean feat, as PEA itself is a relatively new science and many challenges still exist in the field of event attribution ̶ a field of research concerned with the process by which the causes of behavior and events can be explained. In this instance, the idea was to study each extreme weather event individually to determine if human-induced climate change may have added to the intensity or likelihood of the event occurring. PEA is a growing science within this field and relies on the availability of long-term meteorological observations and the reliability of climate model simulations. In terms of migration and the accompanying econometric methods, the complexity of this work is mainly in data capturing.

“The difficulty with migration data capturing is at the start – before you can capture anything, you must ascertain how the data is defined, as different countries define mobility in different ways. For instance, it could be time – where did you live one year ago as opposed to five years ago? That’s the first complexity. Then you must work out who collects data on who – in Europe, we have fundamental freedom of movement within the EU, so unless you file for residency, your movement is not recorded. Another complexity is because we want to see if climate change is part of the driver ̶ directly or indirectly. We need to know not just where people are now, but where they have been and where they came from, so we can match the climate with their movements. All of this highlights how difficult it is to carry out this type of analysis,” Thalheimer adds.

In Somalia, the team relied on previously collected forced migration data, for example, from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). These UNHCR datasets collected in Somalia were comprehensive and included not only origin and destination information but also a categorization of the primary reason for the displacement.

© Aleksandr Frolov | Dreamstime.com

The investigation homed in on one extreme weather case study in the region: The April 2020 heavy rainfall in Southern Ethiopia, which led to several severe flooding events in South Somalia. In this particular case, however, no appreciable connection could be made between human-induced climate change and the resultant displacement. Despite this somewhat chastening outcome, the achievement of this study is not proving a definitive attributable link between human-induced climate change and the April 2020 rainfall, but rather the construction of the adjustable attribution framework presented that can be applied directly to other events and displacement contexts.

As previously mentioned, there are, however, limitations to this novel methodology, especially in regions like Somalia that lack exhaustive observational weather and displacement data. According to Thalheimer, exploring ways of effectively applying this framework in countries vulnerable to climate change will be particularly important going forward.

“Event attribution studies do not usually form the basis of climate migration analysis, disaster risk reduction, or adaptation strategies. Yet, to respond appropriately to these impacts and affected populations, we must develop a comprehensive and detailed understanding of the nature of these impacts, as well as knowledge on how these might evolve over time. Event attribution is a tool we can employ to do this,” she concludes.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

May 6, 2020 | COVID19, Risk and resilience

By Finn Laurien, researcher in the IIASA Risk and Resilience Program and Reinhard Mechler, Acting Program Director IIASA Risk and Resilience Program

The global COVID-19 crisis is challenging the social fabric of countries and communities across the globe. Interventions such as lockdowns, social distancing measures, and economic stimulus packages have been introduced to reinforce societal resilience. The resilience of national health systems is particularly in the spotlight – primarily keeping occupancy numbers of intensive care beds under a critical threshold, as well as improving access to basic health services for people infected with the virus, and ensuring that infections do not spread further.

© piyushpriyanka|Unsplash

At the same time, many COVID-19 affected regions and communities are confronted with additional multiple threats, including disaster and climate risks like flooding. For example, South Asia will be facing the monsoon season soon, and cyclones have already ravaged islands in the Pacific. So the question becomes, how do we support communities in preparing for and building resilience to such compound events like disasters AND infectious diseases?

Resilience has emerged as a system-based concept that explains how systems respond to shocks. IIASA has a long history of conceptualizing and assessing resilience. In partnership with members of the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance (ZFRA), IIASA has co-developed an innovative approach called the Flood Resilience Measurement for Communities (FRMC) that measures the various facets of what builds resilience against flood risk at community levels. The FRMC consists of a holistic framework and an indicator-based assessment tool. It measures resilience before and after disasters at the community level – where people feel the impacts acutely and work together to take action. We define resilience widely in terms of a systems-thinking and development-centric conceptualization: “The ability of a system, community or society to pursue its social, ecological and economic development and growth objectives, while managing its disaster risk over time in a mutually reinforcing way.”

The FRMC measures resilience across a number of indicators that are collected through humanitarian and development NGO Alliance partners in communities in Asia, Europe, Latin America, and North America. It provides vital information for decision makers by prioritizing the resilience-building measures most needed by a community. At community and higher decision-making levels, measuring resilience also provides a basis for improving the design of public or privately funded programs to strengthen disaster resilience.

One of the seven themes that has been defined as a key aspect from the FRMC systems thinking approach is “Life and Health”, which is also relevant when looking at COVID-19 and includes access to and availability of healthcare facilities; strategies to maintain or quickly resume interrupted healthcare services; safety knowledge and Water and Sanitation (WASH).

Insights into dealing with COVID-19

In a recent research paper we analyzed FRMC data collected in 118 communities across nine countries in Asia, Latin America, and the US and explored which capacities or capitals contribute most to community disaster resilience. We identified multiple interactions, for instance, how action on bolstering health also contributes to social capital. There are two takeaways from this research that are relevant to other compound events, including the COVID-19 pandemic.

First, fair and functioning health systems play a key role in building resilience against compound risk – against flood as well as against other stresses that lead to negative health outcomes. Strategies that enable interrupted health systems to quickly resume are critical, and need to be in place before a disaster strikes.

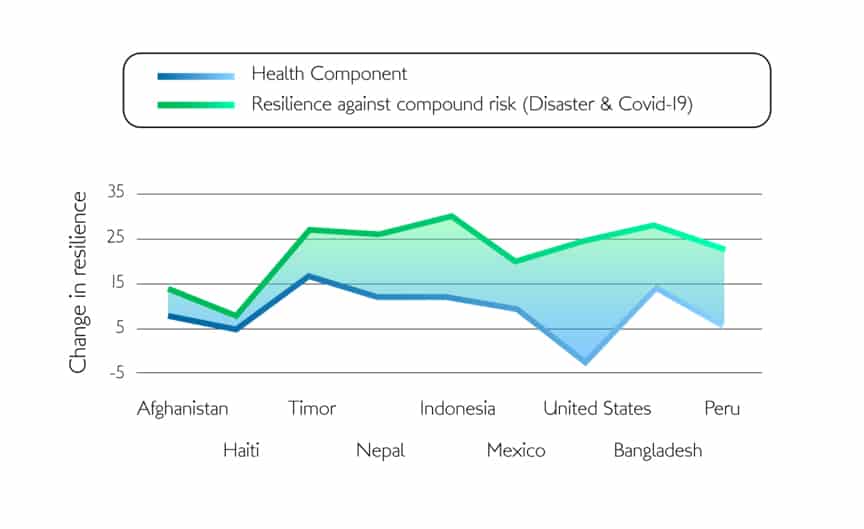

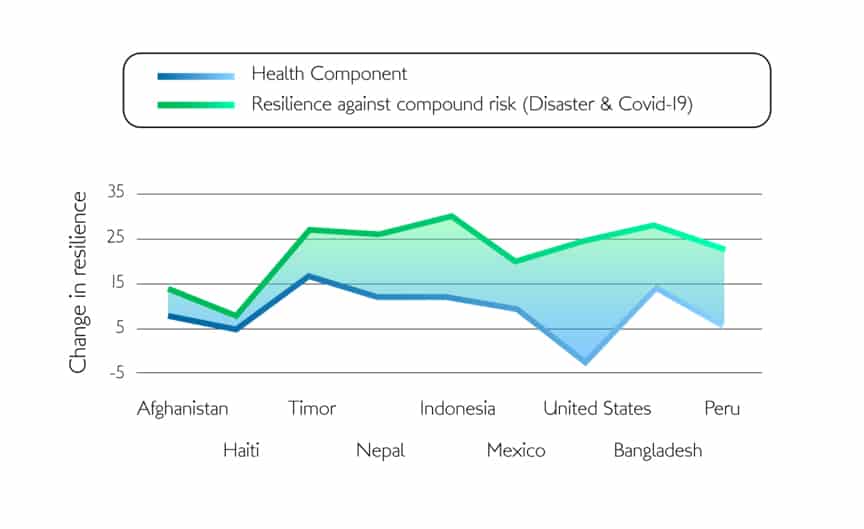

In the communities where ZFRA conducted FRMC studies, disaster resilience and the health component scored relatively low at the beginning. However, when interventions such as household health-related trainings in Mexico, or hospital capacity assessments in Nepal, were implemented (with our measurement tool running), the health component increased for almost all countries (except for the USA) (see blue line in Figure 1). As the health component is a key part of resilience it contributed to disaster resilience overall, including ‘compound risks’ (green line in Figure 1). This means that (further) accelerating investments into health services (e.g., as part of COVID-19 response and recovery packages) leads to additional benefits for other shocks.

Figure 1: Between 2013 and 2018, increased community resilience can be attributed to resilience against compound risk (green line) and includes a health component (blue line). The difference between the two lines indicates the attribution of the increase in specific resilience to flood hazard.

A second takeaway is that through a so-called ‘multifunctionality’ effect, co-benefits are induced. This provides evidence of a virtuous cycle effect where higher resilient capacity in one area fosters communities’ resilience capacity for other functions. As community functions and outcomes are connected in a community system, improved access to health services can generate co-benefits (e.g., healthier individuals attain higher levels of livelihoods and build more social networks, which again build resilience during a shock). This has been well understood in the theoretical literature, and our analysis for the first time provides needed evidence at community level for flood and disaster risk.

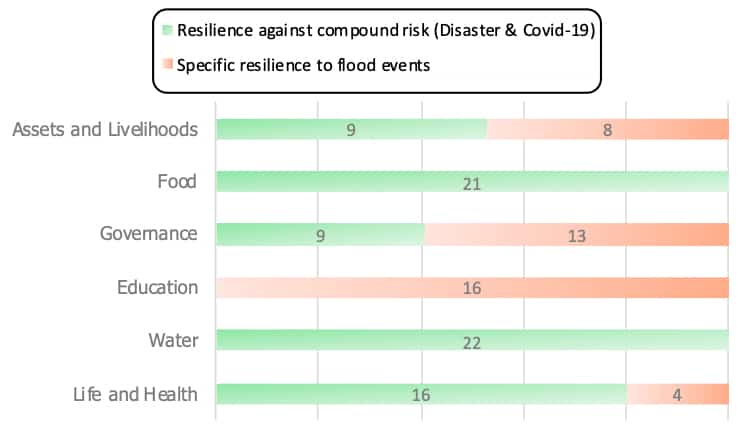

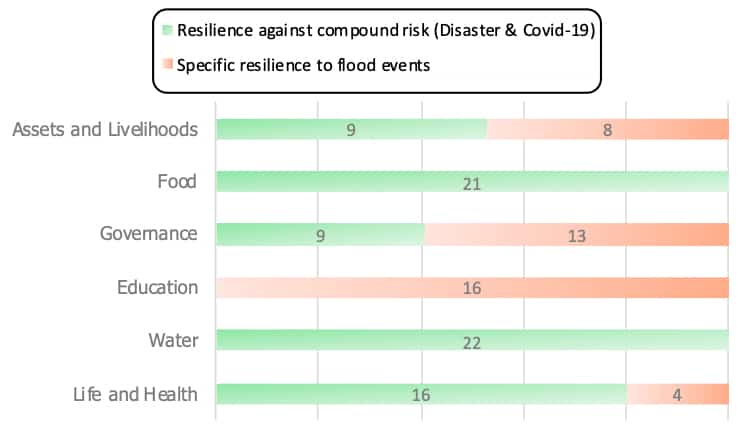

If these co-benefit effects are taken into account, we find evidence that Food and Water strategies (see Figure 2) can be most efficient in building resilience to both adverse flood and health events. In fact, our sources of resilience indicate that the capacity in the Food and Water dimensions also foster health resilience.

Risk awareness is hazard-specific but can be integrated into packages that tackle risk generally. For example, health relevant interventions for infectious diseases (e.g., appropriate hygiene measures) can be integrated into flood evacuation plans. A best-practice example from our work are the campaigns and fairs carried out in Mexico and Nepal targeting educational awareness on health-related impacts during flood events.

Going forward with resilience thinking

Figure 2: Attribution of flood resilience to health component. Some dimensions show a similar pattern in building both flood and health resilience. Other flood-related efforts are too specific and cannot be attributed to resilience against COVID-19.

There is growing recognition by researchers, policymakers, and practitioners of the need to address compound risks in a development-centric way, tackling multiple threats with a focus on human wellbeing, rather than on hazards only. The COVID-19 crisis calls for donors, national governments, civil society, and communities to invest in comprehensive approaches that create multiple benefits.

Our system-based resilience research shows that using a systems resilience assessment at community level can identify direct short- and longer-term benefits. Investing in capacities builds resilience against compound risk such as flooding and infectious diseases. Investment into programs that ramp up health systems and WASH creates multiple benefits in terms of tackling COVID-19 and disaster and climate risks simultaneously. In the context of the upcoming monsoon and hurricane season, this means COVID-19 response and recovery packages need to invest in measures that also reduce social and economic impacts from COVID-19 under flood hazards. Additionally, diversifying household income strategies is high among the measures that unlock multiple co-benefits against compound risks. As action on COVID-19 (hopefully) moves from crisis response to recovery, such measures should be part and parcel of a post-COVID-19 recovery process, reducing the risk of vulnerable groups falling into poverty traps.

References:

Laurien, F., Hochrainer-Stigler, S., Keating, A., Campbell, K., Mechler, R., & Czajkowski, J. (2020). A typology of community flood resilience. Regional Environmental Change, 20(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-020-01593-x

Keating, A., Campbell, K., Mechler, R., Magnuszewski, P., Mochizuki, J., Liu, W., Szoenyi, M., McQuistan, C. (2016). Disaster resilience: What it is and how it can engender a meaningful change in development policy. Development Policy Review 35 (1): 65-91

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Dec 18, 2019 | Climate Change, Risk and resilience

Making use of mutuality-solidarity-accountability-transparency principles

By Teresa M. Deubelli, researcher in the IIASA Risk and Resilience Program and Reinhard Mechler, Deputy Program Director IIASA Risk and Resilience Program

The Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM) for Loss and Damage and its ongoing review were hot topics at COP25. Hopes for a step-change on the issue of finance to scale up action and support have not been translated into action. Negotiating Parties remain divided over the way forward and the question of what kind of finance and for whom. We suggest to build on principles of risk governance, including insurance, and international cooperation – mutuality, solidarity, accountability and transparency – and to combine these in novel ways in order to upscale action on both averting and minimizing as well as addressing loss and damage under the WIM in a manner that truly shows responsibility for responding to the climate crisis.

COP25 Madrid, Spain © Reinhard Mechler | IIASA

Why do we need a step-change on Loss and Damage finance?

Hard limits to adaptation are creating situations beyond adaptation; think for example of communities fleeing desertification or sea-level rise that can only retreat so far. The WIM has made substantial strides on its objectives to advance knowledge and exchange since its creation, but now the time is ripe to take the necessary steps to also move forward on addressing loss and damage from climate change.

So far, this third WIM priority has mostly been addressed through insurance approaches, such as the Fiji Clearing House. While there is value in scaling up risk transfer options, insurance comes with drawbacks: insurance premium costs often exceed financial capacities of vulnerable groups or may result in a false sense of protection that undermines further resilience-building action. Additionally, risk transfer options remain focused on sudden onset events.

Loss and damage from climate change is not just linked to sudden events; sea-level rise, desertification, and glacial melting take years to unfold, but once these tipping points are reached, recovery and reconstruction, and thus the typical logic of humanitarian assistance, are out of the question. As the climate crisis spirals forward tipping points may be reached sooner than expected, also challenging the sustainability of resilience building actions within the framework of development cooperation

How to make a principled case to generate support for addressing loss and damage?

Most vulnerable countries agree that the WIM needs to advance on enhancing action and support for addressing loss and damage from climate change. Discussions at COP25 focused heavily on the issue of mobilizing finance for addressing loss and damage, but little headway was made, as views on the exact modalities of finance and its access differ vastly amongst Parties. Unfortunately, this means that the ongoing WIM review faces a certain risk of replicating the stalemate that characterised the Paris Agreement negotiations on the question of liability, when notions of compensatory justice were crossed out from Article 8 at the request of several developed, high emitting countries.

In order to propel the discourse forward in future rounds of climate talks and in the WIM review, We suggest to build on principles of risk governance, including insurance, and international cooperation – mutuality, solidarity, accountability and transparency – and to combine these in novel ways in order to upscale action on both averting and minimizing as well as addressing losses and damages under the WIM:

- As the underlying insurance principle, mutuality is found in risk pooling and sharing – several parties pool funding to mobilize finance for offsetting losses in times of crisis, essentially spreading out and mutualizing risks across participants.

- Solidarity describes the shared responsibility for supporting others in times of hardship. As a principle it underpins development cooperation and humanitarian assistance and is at the heart of the Agenda 2030.

- Accountability links actions with outcomes in a mutually responsible relationship and is motivated by a perceived ethical or legal obligation for supporting each other in addressing climate-attributed loss and damage.

- As a transversal principle, transparency adds itself as a critical enabler of a finance architecture that expands the WIM to support those who are suffering loss and damage in ways that cannot be addressed through business-as-usual.

All principles lend themselves to the WIM as a ground for advancing on its priority to enhance action and support for addressing loss and damage from climate change, but also offer inspiration for thinking out novel ways to advance further.

What could this mean concretely?

These deliberations are not merely theoretical in nature but are seeing attention. For example through the further development of the (ARC) pool, a regional drought pool established in 2012 as a specialised agency of the African Union to help member states improve their planning, preparation and response capacities. Disbursements from the pool support participating governments’ drought relief efforts, with requirements on how these are used (transparency and accountability).

Initial donor funding (solidarity) and ARC member annual premium payments (mutuality) capitalise the ARC. The pool is currently preparing for the launch of an additional capitalization mechanism, the Extreme Climate Facility (ARC-XCF). This would issue climate catastrophe bonds, resulting in pay-outs whenever the index tracking frequency and magnitude of droughts and extreme temperature exceeds a predefined threshold (transparency). While using the capital markets to access additional funding needs, accountability for climate change is factored in to some extent through the international support divested to setting up the mechanism.

The ARC-XCF is one way to address loss and damage and offers practical inspiration for setting up facilities for addressing loss and damage under the WIM. Especially where hard limits are pushed beyond adaptation and traditional insurance is no longer feasible, drawing on the experience from such risk pooling facilities can be useful input for setting up a specific facility under the WIM that supports those at the frontiers of climate change.

In doing so, it will be important to keep the principles of international cooperation and insurance – mutuality, solidarity, accountability and transparency – in mind to equitably address loss and damage, especially where risks are increasingly intolerable and beyond adaptation.

References:

Deubelli, T. and Mechler, R. (2019). Finance for Loss & Damage: Towards a comprehensive principled approach, unpublished.

Linnerooth-Bayer, J. Surminski, S., Bouwer, L., Noy, I., Mechler, R., McQuistan, C. (2018). Insurance as a Response to Loss and Damage? In: Mechler R, Bouwer L, Schinko T, Surminski S, Linnerooth-Bayer J (2018). Loss and Damage from climate change. Concepts, methods and policy options. Springer, Cham: 483-512

Mechler R, Bouwer L, Schinko T, Surminski S, Linnerooth-Bayer J (2018). Loss and Damage from climate change. Concepts, methods and policy options. Springer, Cham.

This blog is reposted from a Flood Resilience Portal blog.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Oct 31, 2019 | Climate, Risk and resilience

By Finn Laurien, research assistant at the IIASA Risk and Resilience (RISK) Program, and doctoral student at the Vienna University for Economics and Business.

A major challenge in understanding community flood resilience is the lack of an empirically validated measure of it. To plug this gap the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance (ZFRA) developed the Flood Resilience Measurement for Communities (FRMC). In the first phase of the Alliance we applied the FRMC tool in 118 communities in nine different countries. This is what we learnt from it.

What is the Flood Resilience Measurement for Communities?

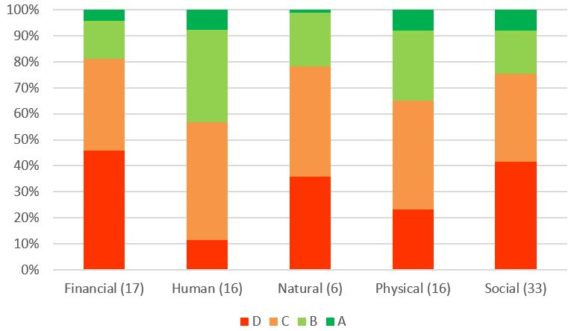

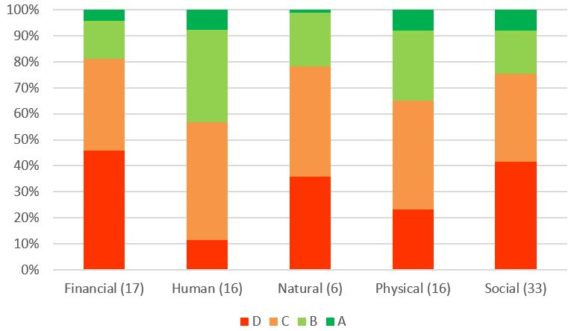

The FRMC approach holistically measures a set of “sources of resilience” before a flood happens (e.g. household savings or whether a community has a flood recovery plan) and looks at the post-flood impacts afterwards (e.g. level of loss and recovery time). The FRMC framework is built around the notion of five types of capital (the 5Cs: human, social, physical, natural, and financial capital) and the 4Rs of a resilient system (robustness, redundancy, resourcefulness, and rapidity). The data is collected and assessed via an integrated and hybrid platform. Each source of resilience is graded from A to D (best practice to significant below good standard) providing communities and decision-makers with an overview of the level of resilience capacity.

The 5 Capitals and 4 sources of resilience © Paulo Cerino

What did we learn from this large-scale analysis of community flood resilience?

Human and physical capital had the most sources assigned an A or B grade. The highest rated sources are education (value and equity), flood exposure perception, knowledge and awareness, communication, water, personal safety as well as health and sanitation. This could be a result of flood mitigation interventions traditionally being focused on building people’s skills and knowledge and/or physical structures.

Overview of frequency of grades for the sources of resilience by capital. Note: Number in bracket of capitals indicates the number sources in that capital. (Source: Campbell et al., 2019)

Despite the source-specific guidance and standardized data, grading is largely a judgment-based process and the FRMC includes a box where the assessor indicates how confident they are in the assigned grade. Since the trained assessors are practitioners with local understanding of the community the grades are influenced by their field expertise. The assessors were generally confident in the assigned grades and we found that their confidence increased the more data collection methods that were used.

Linking flood resilience and community characteristics

The FRMC was used in a range of different communities in developing and developed countries in contexts ranging from urban to rural and with some difference in past experience of flooding.

We discovered a correlation between poverty and lack of flood resilience and also found that having experienced very severe floods reduced a community’s level of resilience while experiencing frequent but less severe floods could help contribute to resilience, potentially by providing communities with relevant experience to adapt.

Does the FRMC process result in different interventions?

A key question we asked is whether the process of carrying out the baseline measurement and sharing results with the community resulted in interventions that were substantially different from what would have been implemented anyway. We find that it did, though to somewhat varying degrees.

Country teams overwhelmingly reported that the process helped them, their stakeholders, and communities to see flood resilience in a much more holistic way. For example, by broadening the perspective of flood resilience beyond that of physical infrastructure to also include social capital. The FRMC process influenced the implementation of a wide range of interventions, showing the breadth of the underlying conceptualization of resilience. The purpose of the FRMC approach is to help communities holistically strengthen their resilience and the broad range of interventions shows that this has worked.

Many country programs revised their project plans, log-frames and budgets as a result of the baseline measurement. Program staff highlighted how welcome it would be if other funders followed Zurich’s lead and allowed for similar in-depth analysis prior to intervention design and flexibility to act on the learning coming out of it to ensure the most effective intervention design.

What’s next for the FRMC?

This testing and data analysis has fed into the revision process for the development of the Next Generation FRMC which is currently being scaled to many more communities.

As the tool and measurement gets used in more communities and as part of more decision-making processes for flood resilient investments, we hope the usefulness and relevance of the tool will be demonstrated and adopted by many more organizations working to build community flood resilience.

Abel from Practical Action interviewing Consuelo, a community member in San Miguel de Viso, Peru as part of FRMC data collection ©Giorgio Madueño –

Reference:

Campbell KA, Laurien F, Czajkowski J, Keating A, Hochrainer-Stigler S, & Montgomery M (2019). First insights from the Flood Resilience Measurement Tool: A large-scale community flood resilience analysis. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 40: e101257. DOI:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101257. http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/id/eprint/16027/

Access available resources on the FRMC here.

This blog is reposted from a Flood Resilience Portal blog.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Sep 4, 2019 | Austria, Environment, Risk and resilience, Women in Science

By Marlene Palka, research assistant in the IIASA Risk and Resilience Program

Marlene Palka discusses the work done by the IIASA FARM project, which has been investigating drought risk management in Austria for the past three years.

Future climate projections forecast an increase in both the frequency and severity of droughts, with the agricultural sector in particular being vulnerable to such extreme weather events. In contrast to most other climatic extremes, droughts can hit larger regions and often for extended periods – up to several months or even years. Like many other countries, Austria has been and is expected to be increasingly affected, making it necessary to devise a management strategy to mitigate drought damages and tackle related problems. The FARM project – a three year project financed by the Austrian Climate Research Program and run by the IIASA Risk and Resilience and Ecosystems Services and Management programs – kicked off in 2017 and has been investigating agricultural drought risk management both in a broad European context, and more specifically in Austria.

Young sunflowers on dry field © Werner Münzker | Dreamstime.com

Austria represents a good case study for agricultural drought risk management. Despite the agricultural sector’s rather small contribution to the country’s economic performance, it still has value and represents an important part of the country’s historical and cultural tradition. Around 80% of Austria’s total land area is used for agricultural and forestry activities. Equally important is its contribution to the preservation of landscapes, which is invaluable for many other sectors including tourism.

Globally, agricultural insurance is a widely used risk management instrument that is often heavily subsidized. Apart from the fact that the concept is increasingly being supported by European policymakers – the intention being that insurance should play a more prominent role in managing agricultural production risk – more and more voices from other sectors are calling for holistic management approaches in agriculture with the overall aim of increasing the resilience of the system.

There is a well-established mutual agricultural insurance company in Austria, which has high insurance penetration rates of up to 75% for arable land, and comparably high subsidies of up to 55% of insurance premiums. It is also encouraging to note that recent policy decisions support the timeliness of drought risk: in 2013, the Austrian government paid EUR 36 million in drought compensation to grassland farmers and in 2016, premium subsidies of 50% were expanded to other insurance products, including drought, while ad-hoc compensation due to drought was officially eliminated. In 2018, the subsidy rate was further increased to 55%. In light of these prospects, we investigated the management option space of the Austrian agricultural sector as part of the FARM project.

The 2018 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report on monitoring and evaluation of agricultural policies claims that efficient (drought) risk management in agriculture must consider the interactions and trade-offs between different on-farm measures, activities of the private sector, and government policies. The report further argues that holistic approaches on all management levels will be vital to the success of any agricultural management strategy.

In the course of our work, we found that agricultural drought risk management in Austria lacks decision making across levels. Although there is a range of drought management measures available at different levels, cooperation that includes farms, public and private businesses, and policy institutions is often missing. In addition, measures to primarily and exclusively deal with drought, such as insurance and irrigation, are not only limited, but (as we found) are also less frequently implemented.

As far as insurance is concerned, products are still being developed, and penetration rates are currently low. Drought risk is also highly uncertain, making it almost impossible to offer extensive drought insurance products. Irrigation is perceived as the most obvious drought management measure among non-agronomists. Simply increasing irrigation to deal with the consequences of drought could however lead to increased water demand at times when water is already in short supply, while also incurring tremendous financial and labor costs and additional stress to farmers. With that said, a large number of agricultural practices may also holistically prevent, cope with, or mitigate droughts. For example, reduced soil management practices are low in operating costs and prevent surface run-off, while simultaneously maintaining a soil structure that facilitates increased water holding capacity. Market futures might also stabilize farm income and therefore allow for future planning such as the purchase of irrigation equipment.

A workshop we held with experts from the Austrian agricultural sector further highlighted this gap. Thinking (not even yet acting) beyond the personal field of action was rare. The results of a survey we conducted showed that farmers were experiencing feelings of helplessness regarding their ability to manage the negative effects of droughts and other climatic extremes despite the implementation of a broad range of management solutions. One way to explain this could be a lack of cooperation across different management levels, meaning that existing efforts – although elaborate and well-proven – potentially reach their limit of effectiveness sooner rather than later.

Due to the more complex effects of any indirect/holistic drought management measure, we need tailored policies that take potential interdependencies and trade-offs into account. With evidence from the FARM project, my colleagues and I would like to emphasize an integrated risk management approach, not only at farm level but also in all relevant agencies of the agricultural sector in an economy. This will help to secure future production and minimize the need for additional public financial resources. Our findings not only contribute to ongoing high-level discussions, but also underpin the resulting claim for more holistic (drought) risk management with bottom-up data from our stakeholder work.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 27, 2019 | Climate Change, Environment, Risk and resilience, Young Scientists

By Luiza Toledo, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2019

2019 YSSP participant Regina Buono investigates how the law can support or impede the use of nature-based solutions and help facilitate adaptation to climate change.

Recognizing the need for a systemic change is the first step to overcoming environmental challenges like climate change. In theory, governance systems can be designed and arranged to facilitate and embrace adaptation to climate change. Developing a legal framework that supports such an adaptation is, however, a big challenge. Learning how to manage the environmental crisis we currently find ourselves in while still being able to grow economically further complicates matters. According to Regina Buono, a participant in this year’s IIASA Young Scientist Summer Program (YSSP), nature-based solutions could be an alternative option that offers a multitude of benefits in terms of how this dual goal of economic growth and sustainability can be achieved. Buono’s research will contribute to IIASA as a partner in the EU Horizon 2020 project, PHUSICOS, which is demonstrating how nature-based solutions can reduce the risk of extreme weather events in rural mountain landscapes.

Outdoor green living wall, vertical garden on modern office building | © Josefkubes | Dreamstime.com

Nature-based solutions are actions to protect, manage, or restore natural ecosystems that address societal challenges, such as water security, pollution, or natural disasters – sometimes simultaneously. These solutions take advantage of the system processes found in nature – such as the water regulation function of wetlands, the allowance of natural space in floodplains to buffer flooding impacts, water storage in recharged aquifers, or carbon storage in prairies – to tackle environmental problems. This concept is now widely used to reframe policy debates on biodiversity conservation, climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies, urban resilience, as well as the sustainable use of natural resources.

As part of her research, Buono is exploring how the law can support or impede the use of nature-based solutions and considering how we can make legal systems more adaptive so they can help facilitate societal adaptation to a more uncertain world under ongoing and future climate change.

“My research is about using the law as a tool that works for us, rather than one that, because of its historic interest in stability, gets in the way,” she says.

Regina Buono, YSSP participant. | © Buono

Buono started her career as a lawyer based in the US. In her first job she was assigned to work with water issues and according to her, it was “love at first sight”. Following that first assignment, she continued to work on finding market-based solutions for issues related to endangered species. She decided to pursue a PhD in public policy in 2016, and soon after was asked to join the external advisory board to the Nature Insurance Value: Assessment and Demonstration (NAIAD) project in Europe. While attending the first meeting, she realized that there were no lawyers or legal scholars among the project researchers. As a lawyer, she could see that there was a gap in understanding how law and regulations would impact the uptake, development, and proliferation of nature-based solutions.

Working with NAIAD, she developed her PhD dissertation to address this gap and advance understanding around the role of the law in nature-based solutions, both in terms of governance in implementation and practice and the potential for governance innovation that better supports and promotes future adaptation.

“My YSSP project here at IIASA focuses on the city of Valladolid, Spain, and examines the legal context around the implementation of a collection of nature-based solution projects. I am trying to draw insights from these that could perhaps also be applied to other cases,” she explains.

Buono is doing a critical qualitative study that integrates analyses of interviews and policy documents using NVivo, a qualitative data analysis computer software package specifically designed to work with very rich text-based and/or multimedia information, together with legal analysis. She says that there is still a lot of work to be done to adapt to climate change and an interdisciplinary cross-sector effort will be necessary.

The preliminary results from her YSSP research point to a number of constraints and facilitating factors related to law and regulation. She says that the lack of explicit legal authorization for nature-based solutions that she identified in her study, strict water quality regulations, and bureaucratic hurdles could be some of the factors that constrain the implementation of nature-based solutions. However, flexibility in the law and a polycentric governance structure was identified as facilitating factors that encourage local entities to opt for nature-based solutions.

Buono hopes that her research will help decision makers to assess and address legal components that guide, structure, or impede the use of nature-based solutions, and to consider how the law could be evolved to create a more enabling environment for more adaptive governance arrangements that would better support nature-based solutions.

“Our policies and infrastructure are going to have to change to be able to deal with the impacts that we are already experiencing. Nature-based solutions and a shift toward adaptive governance could help us navigate more gracefully in these important transitions,” she concludes.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.