Jan 17, 2020 | Climate Change, Demography

By Roman Hoffmann, Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (IIASA, VID/ÖAW, and University of Vienna), Vienna Institute of Demography, Austrian Academy of Sciences, and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research.

Taking action to combat climate change and its impacts is urgent and vital to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Although per capita emissions are still highest in high-income countries, several emerging low and middle-income countries have seen a rise in carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions in recent years. While much of that rise was due to increased (export-oriented) industrial activities, changing lifestyle, consumption, and mobility patterns also played a significant role. How people can be encouraged to behave in an environmentally friendly way is a fundamental question for climate change mitigation. Despite a call for a stronger emphasis on demand-side solutions in mitigation strategies, little is known about the determinants of pro-environmental behaviors of people from the developing world.

© Roman Hoffman | IIASA

In a study with IIASA researcher Raya Muttarak, which has recently been published in Environmental Research Letters, we found that education significantly contributes to increasing pro-environmental orientations and actions among low-income households in the Philippines. As an emerging lower-middle-income country, the Philippines are faced with severe environmental issues, such as pollution, deforestation, and environmental degradation. Already in the 1990s, public policy has responded to these challenges by developing several environmentally-focused learning initiatives and by making environmental education a fundamental pillar of the national school curriculum. Today, according to the World Value Survey, more than 73% of the population can identify with a person who gives importance to looking after the environment compared to 55% and 63% in the neighboring countries Thailand and Malaysia, respectively.

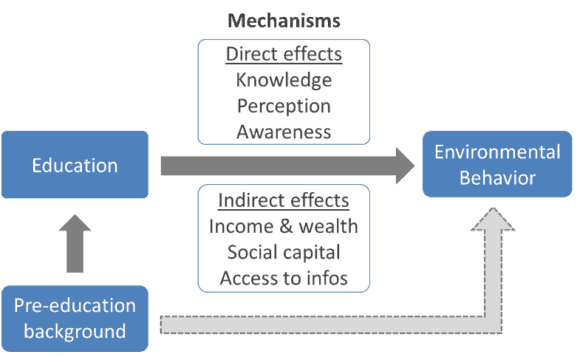

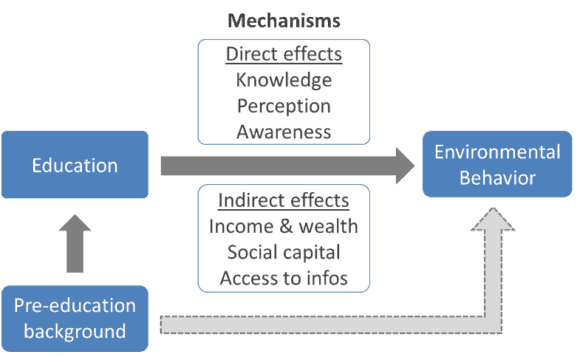

Figure 1 – Conceptual framework explaining the direct and indirect channels through which education influences environmental behavior. Note: The empirical design controls for the respondents’ pre-education background and indirect channels of influence allowing us to capture the direct effects of education on pro-environmental behaviors.

Based on original cross-sectional survey data, we found education to be positively related to pro-environmental behaviors such as recycling, proper garbage disposal, and planting trees. An additional year of schooling is estimated to increase the probability of carrying out climate-friendly actions by a substantial 3.3%. Going beyond previous research, we explored some of the underlying mechanisms through which education influences environmental behavior. . While knowledge and awareness raising are both important, it is found that education influences behavior mainly by increasing awareness about the anthropogenic causes of climate change, which may consequently affect the individual perception of self-efficacy in reducing human impacts on the environment. This is in line with the environmental psychology literature, which finds that poor understanding of the connection between human actions and climate change influences the perception of one’s ability to control and take action against it. People will become active only if the perceived likelihood of achieving a desired outcome is high enough. Education can hence play a vital role in promoting a better understanding of climate change and in raising awareness about the impacts of human activities.

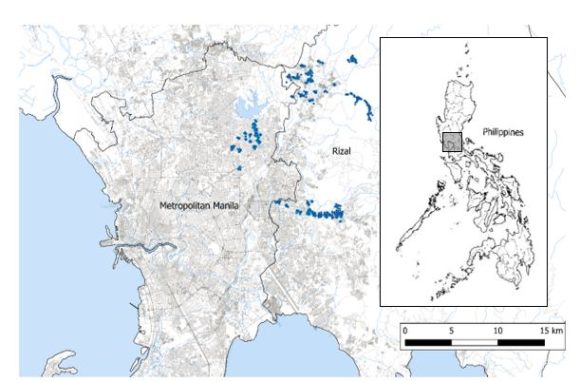

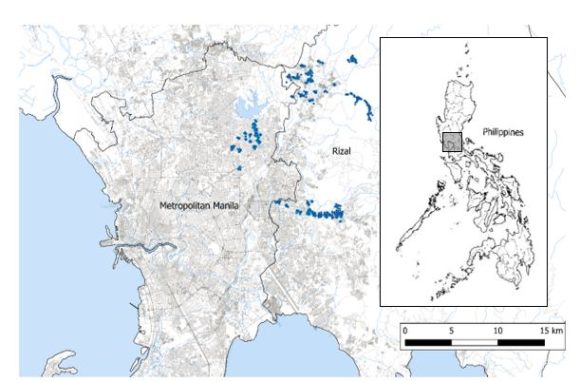

Figure 2 – Map of study areas with locations of respondents’ homes. The study areas encompassed both more urban and rural areas located in Rizal province towards the East of the National Capital Region

In line with recent efforts of the international community to promote education for sustainable development, our study provides solid empirical evidence confirming the important role of education in climate change mitigation efforts. Investments in education can make an important contribution in raising awareness and ultimately in promoting green behavior helping to reduce the human impacts on the global climate system. In this regard, while it is important to provide learners with the necessary tools and capabilities to undertake pro-environmental actions, it is also key to raise their perceived self-efficacy. Education should thus not only focus on the transfer of knowledge and information, but also highlight the importance of the individual contribution in mitigating the harmful consequences of global environmental change.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Nov 12, 2019 | Austria, Communication, Demography, Women in Science

By Nadejda Komendantova, researcher in the IIASA Advanced Systems Analysis Program

Nadejda Komendantova discusses how misinformation propagated by different communication mediums influence attitudes towards migrants in Austria and how the EU Horizon 2020 Co-Inform project is fostering critical thinking skills for a better-informed society.

© Skypixel | Dreamstime.com

Austria has been a country of immigration for decades, with the annual balance of immigration and emigration regularly showing a positive net migration rate. A significant share of the Austrian population are migrants (16%) or people with an immigrant background (23%). The migration crisis of 2015 saw Austria as the fourth largest receiver of asylum seekers in the EU, while in previous years, asylum seekers accounted for 19% of all migrants. Vienna has the highest share of migrants of all regions and cities in Austria, and over 96% of Viennese have contact with migrants in everyday life.

Scientific research shows that it is however not primarily these everyday situations that are influencing attitudes towards migrants, but rather the opinions and perceptions about them that have developed over the years. Perceptions towards migration are frequently based on a subjectively perceived collision of interests, and are socially constructed and influenced by factors such as socialization, awareness, and experience. Perceptions also define what is seen as improper behavior and are influenced by preconceived impressions of migrants. These preconceptions can be a result of information flow or of personal experience. If not addressed, these preconditions can form prejudices in the absence of further information.

The media plays an essential role in the formulation of these opinions and further research is necessary to evaluate the impact of emerging media such as social media and the internet, and their consequent impact on conflicting situations in the limited profit housing sector. Multifamily housing in particular, is getting more and more heterogeneous and the impacts of social media on perceptions of migrants are therefore strongest in this sector, where people with different backgrounds, values, needs, origins and traditions are living together and interacting on a daily basis. Perceptions of foreign characteristics are also frequently determined by general sentiments in the media, where misinformation plays a role. Misinformation has been around for a long time, but nowadays new technologies and social media facilitate its spread, thus increasing the potential for social conflicts.

Early in 2019, the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) organized a workshop at the premises of the Ministry of Economy and Digitalization of the Austrian Republic as part of the EU Horizon 2020 *Co-Inform project. The focus of the event was to discuss the impact of misinformation on perceptions of migrants in the Austrian multifamily limited profit housing sector.

Nadejda Komendantova addressing stakeholders at the workshop.

We selected this topic for three reasons: First, this sector is a key pillar of the Austrian policy on socioeconomic development and political stability; and secondly, the sector constitutes 24% of the total housing stock and more than 30% of total new construction. In the third place, the sector caters for a high share of migrants. For example, in 2015 the leading Austrian limited profit housing company, Sozialbau, reported that the share of their residents with a migration background (foreign nationals or Austrian citizens born abroad) had reached 38%.

Several stakeholders, including housing sector policymakers, journalists, fact checkers, and citizens participated in the workshop. Among them were representatives from the Austrian Chamber of Labor, Austrian Limited Profit Housing (ALPH) companies “Neues Leben”, “Siedlungsgenossenschaft Neunkirchen”, “Heim”, “Wohnbauvereinigung für Privatangestellte”, the housing service of the municipality of Vienna, as well as the Austrian Association of Cities and Towns.

The workshop employed innovative methods to engage stakeholders in dialogue, including games based on word associations, participatory landscape mapping, as well as wish-lists for policymakers and interactive, online “fake news” games. In addition, the sessions included co-creation activities and the collection of stakeholders’ perceptions about misinformation, everyday practices to deal with misinformation, co-creation activities around challenges connected with misinformation, discussions about the needs to deal with misinformation, and possible solutions.

During discussions with workshop participants, we identified three major challenges connected with the spread of misinformation. These are the time and speed of reaction required; the type of misinformation and whether it affects someone personally or professionally; excitement about the news in terms of the low level of people’s willingness to read, as well as the difficulties around correcting information once it has been published. Many participants believed that they could control the spread of misinformation, especially if it concerns their professional area and spreads within their networking circles or among employees of their own organizations. Several participants suggested making use of statistical or other corrective measures such as artificial intelligence tools or fact checking software.

The major challenge is however to recognize misinformation and its source as quickly as possible. This requirement was perceived by many as a barrier to corrective measures, as participants mentioned that someone often has to be an expert to correct misinformation in many areas. Another challenge is that the more exciting the misinformation issue is, the faster it spreads. Making corrections might also be difficult as people might prefer emotional reach information to fact reach information, or pictures instead of text.

The expectations of policymakers, journalists, fact checkers, and citizens regarding the tools needed to deal with misinformation were different. The expectations of the policymakers were mainly connected with the creation of a reliable, trusted environment through the development and enforcement of regulations, stimulating a culture of critical thinking, and strengthening the capacities of statistical offices, in addition to making relevant statistical information available and understandable to everybody. Journalists and fact checkers’ expectations on the other hand, were mainly concerned with the development and availability of tools for the verification of information. The expectations of citizens were mainly connected with the role of decision makers, who they felt should provide them with credible sources of information on official websites and organize information campaigns among inhabitants about the challenges of misinformation and how to deal with it.

*Co-Inform is an EU Horizon 2020 project that aims to create tools for better-informed societies. The stakeholders will be co-creating these tools by participating in a series of workshops in Greece, Austria, and Sweden over the course of the next two years.

Adapted from a blog post originally published on the Co-Inform website.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Feb 4, 2019 | Demography, Education, India, Postdoc

By Nandita Saikia, Postdoc Research Scholar at IIASA

What matters more when it comes to preventing unexpected and tragic adult deaths, between the ages of 15 and 60, in low- or middle-income countries? Is it wealth? Or education?

With the advent of demographic and health surveys (DHS), empirical studies documented that the education level of mothers matters more than the wealth of the household when it comes to preventing deaths among children in these countries. However, the same question largely remained unanswered for adults, as such surveys rarely collect information on adult deaths and the socioeconomic status of the dead individuals. In these countries, in general, death registration systems are poor, which again hinders scientific studies addressing this issue.

© Donyanedomam | Dreamstime.com

One possible solution is the clever use of indirect methods or models on census and survey data, developed by demographers to derive rates from limited, deficient and defective data. These methods use indirect information collected by surveys for a different purpose. For example, by using women’s siblings’ survival status, one can estimate maternal mortality, or by using women’s widowhood status, one can estimate male adult mortality.

In our recent study on India, we used one such method, called the Orphanhood method, to document life expectancy differences in adulthood by important socioeconomic characteristics. Because of the reasons mentioned above, there is hardly any scientific evidence on life expectancy differences by education or economic status in India, a country with exceptional cultural and socioeconomic diversity. The importance of studying adult mortality disparity in India also lies in the fact that India experiences relatively higher adult mortality than some of its neighboring countries with similar level of economic development. India’s official statistics shows that adult females belonging to the northeastern state of Assam have more than two times the mortality risk of adult females belonging to the southern state of Kerala. In addition, because of drastic reduction of under five deaths in India in recent years, more and more premature deaths in India will occur in adult age in near future. We used adult parental survival data from a nationally representative large-scale survey, called the India Human Development Survey, 2015-2016, to estimate life expectancy at age 15 in 1998-1999.

We found that lower levels of education of the deceased adults or their offspring, leads to more disparity than any other socioeconomic characteristic, including income status of the offspring, caste, or religion. Literate adults of both sexes at age 15 lived about 3.5 years more than that of their illiterate counterparts. On average, parents of children educated to higher-secondary level (and above) gain an extra 3.8-4.6 years of adult life compared to parents of illiterate children. We found that disparity in adult life by caste and religion is much smaller than disparities arising from educational attainment. For example, female Hindu adults lived 1.3 years more than female non-Hindu adults and male Hindu adults lived 0.9 years more than male non-Hindu adults.

One inherent limitation of indirect demographic methods is that they cannot provide estimates in the most recent years. Despite our estimates referring to a time period about twenty years ago, they are still crucial, as this kind of disparity in adult deaths does not disappear in such a short time span. Our results suggest that investing in education can be more rewarding than anything else to prevent untimely deaths, and to prevent inequalities across population subgroups. Meanwhile, we suggest including appropriate indirect questions in surveys or censuses to track survival status by social group or small geographical area until vital registration systems in countries such as India become fully functional.

Reference:

Saikia N, Bora JK and Luy M (2019). Socioeconomic disparity in adult mortality in India: Estimations using the Orphanhood method. Genus DOI: 10.1186/s41118-019-0054-1 [pure.iiasa.ac.at/id/eprint/15730/]

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 10, 2018 | Demography, Education, Risk and resilience, Young Scientists

© SasinTipchai | Shutterstock

By Sandra Ortellado, 2018 Science Communication Fellow

Science fiction depicts the future with a combination of fascination and fear. While artificial intelligence (AI) could take us beyond the limits of human error, dystopic scenes of world domination reveal our greatest fear: that humans are no match for machines, especially in the job market. But in the so-called fourth industrial revolution, often known as Industry 4.0, the line between future and fiction is a thread of reality.

Over the next 13 years, impending automation could force as many as 70 million workers in the US to find another way to make money. The role of technology is not only growing but also demanding a completely new way of thinking about the work we do and our impact on society because of it.

Rather than focusing on which jobs will disappear because of technological disruption, we could be identifying the most resilient tasks within jobs, says J. Luke Irwin, 2018 YSSP participant. His research in the IIASA World Population program uses a role- and task-based analysis to investigate professions that will be most resilient to technological disruption, with the hope of guiding workforce development policy and training programs.

“We are getting better and better at programming algorithms for machines to do things that we thought were really only in the realm of humans,” says Irwin. “The amount of disruption that’s going to happen to the work industry in the next ten years is really going to impact everyone.”

However, the fear and instability created by the potential disruption elicit chaos, and the response is hard to organize into constructive action. While the resources remain untapped, creativity and imagination are wasted on speculation instead of preparation.

“I couldn’t stand that there’s all this great evidence-based work out there about how we can improve people’s lives and no one is using it,” said Irwin, “I’m trying to align a lot of research and put it in a place where you can compare it and make it more useful and more transferable between the people who would be talking about this: educators, policymakers, employers, and anybody in the workforce.”

Using a German dataset with vocational training as well as time and task information, Irwin will break down jobs into the specific cognitive and physical skills involved and rank the durability of each skill.

Based on the identified jobs and skills, Irwin will go on to draw connections between labor-force capabilities and education policies. His goal is to scale the findings of the most resilient skills to the German labor system so that policymakers and academic institutions can retrain currently displaced workforces and reimagine the future of human work.

After all, while about half the duties workers currently handle could be automated, Mckinsey Global Institute suggests that less than 5% of occupations could be entirely taken over by computers. The future of predictable, repetitive, and purely quantitative work may be threatened, but automation could also open the door for occupations we can’t even imagine yet.

“I think people are amazing and that they have a lot more potential than we are currently capable of fulfilling,” says Irwin.

The World Economic Forum estimates that 65% of children today will end up in careers that don’t even exist yet. For now, an increasingly self-employed millennial generation works insecure, unprotected jobs. The new gig economy, characterized by temporary contracted positions, offers independence but also instability in the labor market.

Without stable work, people lose a sense of security, and that can be dangerous for a policy system that isn’t built to handle uncertainty.

The last industrial revolution caused two or three generations of people to be thrown into poverty and lose everything they had because it was all tied into their job, recalls Irwin.

“Everything gets bad when things are uncertain,” says Irwin, “And this is a very uncertain time. We need to have a better idea of what’s coming so we can actually make some change.”

Irwin, who earned his Master’s in Public Health in 2014, wants his work to have a preventative focus, trying to find those things that not enough people are talking about, but have the potential to make a huge impact on public well-being.

“Especially in the United States, where I live, we’re so tied up with our jobs—it seems like it’s over half our identity,” says Irwin, “We live to work in America.”

In a place like the US, where a job is not only a source of income, but also an identity and a health factor, Irwin’s research offers hope that technological disruption can foster opportunity instead of chaos.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Jun 4, 2018 | Demography, Postdoc, Poverty & Equity, Women in Science

©Nandita Saikia

By Nandita Saikia, Postdoctoral Research Scholar at IIASA

Being an author of a research article on excess female deaths in India in Lancet Global Health, one of the world’s most prestigious and high impact factor public health journals, today I questioned myself: Did I dream of reaching here when I was a little school going girl in the early nineties in a remote village in North East India?

I am the fourth daughter of five. In a country like India, where the status of women is undoubtedly poorer than men even now, and newspapers are often filled with heinous crimes against women, you may be able to imagine what it meant being a fourth daughter. Out of five sisters, three of us were born because my parents wanted a son. My mother, who barely completed her school education, did not want more than two children irrespective of sex, but was pressurized by the extended family to go for a boy after a third daughter and six years of repeated abortions.

I was told in my childhood that I was the most unwanted child in the family. I was a daughter, terribly underweight until age 11, and had much darker skin than my elder sisters and most people from our area, who have fairer skin than average in India. At my birth, my father, a college dropout farmer, was away in a relative’s house and when he heard about the arrival of another girl, he postponed his return trip.

This is a real story, but just one of those still happening in India. The fact that the girls of India are unwanted was observed from the days of early 20th century when it was written in the 1901 census:

“There is no doubt that, as a rule, she [a girl] receives less attention than would be bestowed upon a son. She is less warmly clad, … She is probably not so well fed as a boy would be, and when ill, her parents are not likely to make the same strenuous efforts to ensure her recovery.”

Regrettably, our current study shows that negligence against “India’s daughter” continues to this day.

Discrimination against the girl child can be divided in two categories: before birth and after birth. Modern techniques now allow sex-selective abortion. Despite strong laws, more than 63 million women are estimated to be ‘missing’ in India and the discrimination occurs at all levels of society.

Our present study deals with gender discrimination after birth. We found that over 200,000 girls under the age of five died in 2005 in India as a result of negligence. We found that excess female mortality was present in more than 90% of districts, but the four largest states of North India (Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan, and Madhya Pradesh) accounted for two thirds of India’s total number.

I have to tell you that I was luckier than most girls. Although I was an unwanted child in our extended family, to my mother, this underweight, dark-skinned, little girl was as cute as the previous ones! She gave her best care to her daughter, and she named her “Rani” meaning “Queen” in Assamese. I am still called by this name in my family and in my village.

When I grew up, I asked her several times about her motive for calling me Rani. She always replied: “You were so ugly, the thinnest one with dark skin, I named you as “Rani” because I wanted everyone to have a positive image before seeing you! Also, it is the name of my favorite teacher in high school and she was also a very thin but bright lady!”

The positive conversations with my mother played a crucial role to my desire to have my own identity, and influenced greatly my positive image of myself and my belief that I could do something worthwhile with my life. Much later, when I started my PhD at International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), Mumbai, I was surprised to learn that in Maharashtra, one of the wealthiest states of India, second or third daughters are not even given a name, but instead are called ‘Nakusha’, meaning unwanted.

My parents were passionate about educating their daughters, even with their limited means. My father, who was disappointed at my birth, left no stone unturned for my education! By the time I completed secondary school, our village, as well as neighboring villages, congratulated me during the Bihu celebration (the biggest local gathering) for my good performance in school exams. My parents were proud of me by that time; yet, for some strange reason, they always felt themselves weaker than our neighbors who had sons.

Now, people from our village are proud of me not just because I teach in India’s premier university, or that I take several overseas trips in a year, but because they realize that daughters can equally bring renown to their village; daughters can be married off without a dowry; daughters can equally provide old age care to their parents; daughters too can buy property! Due to this attitude and lower fertility levels, many couples now don’t prefer sons over daughters. In a village of 200 households, there are 33 couples that have either one or two daughters, yet did not keep trying for sons. In my own extended family, no one chooses to have more than two children irrespective of their sex. The situation has changed in my village, but not everywhere.

What is the solution of this deep-rooted social menace? We cannot expect a simple solution. However, my own story convinces me that education can be a game changer, but not necessarily academic degrees. I mean a system by which girls realize their own worth and their capability that they can be economically and socially empowered and can drive their own lives. With the help of education, I made myself from an “unwanted” to a wanted daughter!

The purpose of sharing my story is neither self-promotion nor to gain sympathy, rather to inspire millions of girls, who face numerous challenges in everyday life just because of their gender, and doubt their capability, just like I did in my school days. They can make a difference if they want! Nothing can stop them!

Jan 15, 2018 | Data and Methods, Demography

By Dilek Yildiz, Wittgenstein Center for Demography and Global Human Capital (IIASA, VID/ÖAW and WU), Vienna Institute of Demography, Austrian Academy of Sciences, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis

Social media offers a promising source of data for social science research that could provide insights into attitudes, behavior, social linkages and interactions between individuals. As of the third quarter of 2017, Twitter alone had on average 330 million active users per month. The magnitude and the richness of this data attract social scientists working in many different fields with topics studied ranging from extracting quantitative measures such as migration and unemployment, to more qualitative work such as looking at the footprint of second demographic transition (i.e., the shift from high to low fertility) and gender revolution. Although, the use of social media data for scientific research has increased rapidly in recent years, several questions remain unanswered. In a recent publication with Jo Munson, Agnese Vitali and Ramine Tinati from the University of Southampton, and Jennifer Holland from Erasmus University, Rotterdam, we investigated to what extent findings obtained with social media data are generalizable to broader populations, and what constitutes best practice for estimating demographic information from Twitter data.

A key issue when using this data source is that a sample selected from a social media platform differs from a sample used in standard statistical analysis. Usually, a sample is randomly selected according to a survey design so that information gathered from this sample can be used to make inferences about a general population (e.g., people living in Austria). However, despite the huge number of users, the information gathered from Twitter and the estimates produced are subject to bias due to its non-random, non-representative nature. Consistent with previous research conducted in the United States, we found that Twitter users are more likely than the general population to be young and male, and that Twitter penetration is highest in urban areas. In addition, the demographic characteristics of users, such as age and gender, are not always readily available. Consequently, despite its potential, deriving the demographic characteristics of social media users and dealing with the non-random, non-representative populations from which they are drawn represent challenges for social scientists.

Although previous research has explored methods for conducting demographic research using non-representative internet data, few studies mention or account for the bias and measurement error inherent in social media data. To fill this gap, we investigated best practice for estimating demographic information from Twitter users, and then attempted to reduce selection bias by calibrating the non-representative sample of Twitter users with a more reliable source.

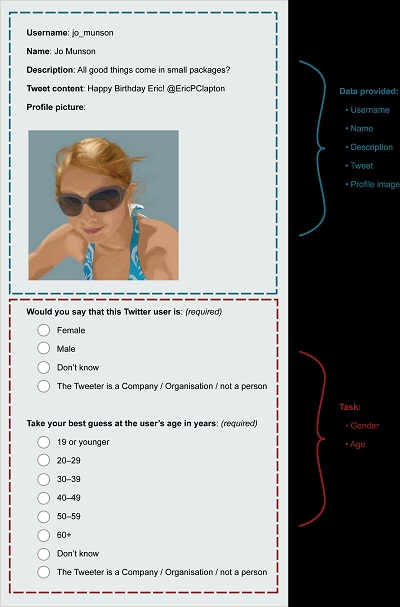

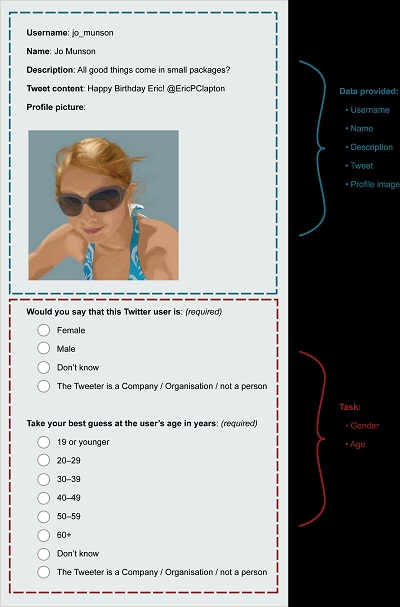

Exemplar of CrowdFlower task © Jo Munson.

We gathered information from 979,992 geo-located Tweets sent by 22,356 unique users in South-East England and estimated their demographic characteristics using the crowd-sourcing platform CrowdFlower and the image-recognition software Face++. Our results show that CrowdFlower estimates age more accurately than Face++, while both tools are highly reliable for estimating the sex of Twitter users.

To evaluate and reduce the selection bias, we ran a series of models and calibrated the non-representative sample of Twitter users with mid-year population estimates for South-East England from the UK Office of National Statistics. We then corrected the bias in age-, sex-, and location-specific population counts. This bias correction exercise shows promise for unbiased inference when using social media data and can be used to further reduce selection bias by including other sociodemographic variables of social media users such as ethnicity. By extending the modeling framework slightly to include an additional variable, which is only available through social media data, it is also possible to make unbiased inferences for broader populations by, for example, extracting the variable of interest from Tweets via text mining. Lastly, our methodology lends itself for use in the calculation of sample weights for Twitter users or Tweets. This means that a Twitter sample can be treated as an individual-level dataset for micro-level analysis (e.g., for measuring associations between variables obtained from Twitter data).

Reference:

Yildiz, D., Munson, J., Vitali, A., Tinati, R. and Holland, J.A. (2017). Using Twitter data for demographic research, Demographic Research, 37 (46): 1477-1514. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2017.37.46

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.