Nov 12, 2019 | Austria, Communication, Demography, Women in Science

By Nadejda Komendantova, researcher in the IIASA Advanced Systems Analysis Program

Nadejda Komendantova discusses how misinformation propagated by different communication mediums influence attitudes towards migrants in Austria and how the EU Horizon 2020 Co-Inform project is fostering critical thinking skills for a better-informed society.

© Skypixel | Dreamstime.com

Austria has been a country of immigration for decades, with the annual balance of immigration and emigration regularly showing a positive net migration rate. A significant share of the Austrian population are migrants (16%) or people with an immigrant background (23%). The migration crisis of 2015 saw Austria as the fourth largest receiver of asylum seekers in the EU, while in previous years, asylum seekers accounted for 19% of all migrants. Vienna has the highest share of migrants of all regions and cities in Austria, and over 96% of Viennese have contact with migrants in everyday life.

Scientific research shows that it is however not primarily these everyday situations that are influencing attitudes towards migrants, but rather the opinions and perceptions about them that have developed over the years. Perceptions towards migration are frequently based on a subjectively perceived collision of interests, and are socially constructed and influenced by factors such as socialization, awareness, and experience. Perceptions also define what is seen as improper behavior and are influenced by preconceived impressions of migrants. These preconceptions can be a result of information flow or of personal experience. If not addressed, these preconditions can form prejudices in the absence of further information.

The media plays an essential role in the formulation of these opinions and further research is necessary to evaluate the impact of emerging media such as social media and the internet, and their consequent impact on conflicting situations in the limited profit housing sector. Multifamily housing in particular, is getting more and more heterogeneous and the impacts of social media on perceptions of migrants are therefore strongest in this sector, where people with different backgrounds, values, needs, origins and traditions are living together and interacting on a daily basis. Perceptions of foreign characteristics are also frequently determined by general sentiments in the media, where misinformation plays a role. Misinformation has been around for a long time, but nowadays new technologies and social media facilitate its spread, thus increasing the potential for social conflicts.

Early in 2019, the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) organized a workshop at the premises of the Ministry of Economy and Digitalization of the Austrian Republic as part of the EU Horizon 2020 *Co-Inform project. The focus of the event was to discuss the impact of misinformation on perceptions of migrants in the Austrian multifamily limited profit housing sector.

Nadejda Komendantova addressing stakeholders at the workshop.

We selected this topic for three reasons: First, this sector is a key pillar of the Austrian policy on socioeconomic development and political stability; and secondly, the sector constitutes 24% of the total housing stock and more than 30% of total new construction. In the third place, the sector caters for a high share of migrants. For example, in 2015 the leading Austrian limited profit housing company, Sozialbau, reported that the share of their residents with a migration background (foreign nationals or Austrian citizens born abroad) had reached 38%.

Several stakeholders, including housing sector policymakers, journalists, fact checkers, and citizens participated in the workshop. Among them were representatives from the Austrian Chamber of Labor, Austrian Limited Profit Housing (ALPH) companies “Neues Leben”, “Siedlungsgenossenschaft Neunkirchen”, “Heim”, “Wohnbauvereinigung für Privatangestellte”, the housing service of the municipality of Vienna, as well as the Austrian Association of Cities and Towns.

The workshop employed innovative methods to engage stakeholders in dialogue, including games based on word associations, participatory landscape mapping, as well as wish-lists for policymakers and interactive, online “fake news” games. In addition, the sessions included co-creation activities and the collection of stakeholders’ perceptions about misinformation, everyday practices to deal with misinformation, co-creation activities around challenges connected with misinformation, discussions about the needs to deal with misinformation, and possible solutions.

During discussions with workshop participants, we identified three major challenges connected with the spread of misinformation. These are the time and speed of reaction required; the type of misinformation and whether it affects someone personally or professionally; excitement about the news in terms of the low level of people’s willingness to read, as well as the difficulties around correcting information once it has been published. Many participants believed that they could control the spread of misinformation, especially if it concerns their professional area and spreads within their networking circles or among employees of their own organizations. Several participants suggested making use of statistical or other corrective measures such as artificial intelligence tools or fact checking software.

The major challenge is however to recognize misinformation and its source as quickly as possible. This requirement was perceived by many as a barrier to corrective measures, as participants mentioned that someone often has to be an expert to correct misinformation in many areas. Another challenge is that the more exciting the misinformation issue is, the faster it spreads. Making corrections might also be difficult as people might prefer emotional reach information to fact reach information, or pictures instead of text.

The expectations of policymakers, journalists, fact checkers, and citizens regarding the tools needed to deal with misinformation were different. The expectations of the policymakers were mainly connected with the creation of a reliable, trusted environment through the development and enforcement of regulations, stimulating a culture of critical thinking, and strengthening the capacities of statistical offices, in addition to making relevant statistical information available and understandable to everybody. Journalists and fact checkers’ expectations on the other hand, were mainly concerned with the development and availability of tools for the verification of information. The expectations of citizens were mainly connected with the role of decision makers, who they felt should provide them with credible sources of information on official websites and organize information campaigns among inhabitants about the challenges of misinformation and how to deal with it.

*Co-Inform is an EU Horizon 2020 project that aims to create tools for better-informed societies. The stakeholders will be co-creating these tools by participating in a series of workshops in Greece, Austria, and Sweden over the course of the next two years.

Adapted from a blog post originally published on the Co-Inform website.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 3, 2018 | Arctic, Climate, Climate Change, Communication, Education, Science and Policy, United Kingdom

© Vadim Nefedoff | Shutterstock

By Sandra Ortellado, 2018 Science Communication Fellow

Around 8,000 kilometers away from Vienna, Austria, hundreds of Arctic coastal communities are at imminent risk from the melting ice and coastal erosion. Indigenous Arctic populations struggle with food insecurity every day, living off small fractions of what their catch would have been only a few years ago. Their culture and their way of life, so dependent on sea ice conditions, are melting away, along with the very root of the Arctic ecosystem.

However, construal level theory, a social psychological theory that describes the extent to which distant things become abstract concepts, tells us that 8,000 kilometers is just far enough for Arctic peoples to lose tangible existence in the minds of urban citizens. Unlike Arctic communities, who experience the direct effects of climate change at each meal, commercialized lower latitude societies don’t have to face the environmental consequences of choosing to drive to the grocery store instead of bike.

Nevertheless, those consequences are very real, even if the impacts on the Arctic and climate system don’t always catch our attention. Sea level will continue to rise for the next several hundred years—it takes 500 years for the deep ocean to adjust to changes at the surface.

On Friday, 22 July, former Chief Scientist of the UK Met Office Dame Julia Slingo and former Chair of the IIASA Council Peter Lemke joined us at IIASA for a joint lecture on climate risk in weather systems and polar regions. The lecture had one underlying theme: in order to make informed decisions on climate change, we need to embrace uncertainty with a broader understanding of what’s possible. That means that the far-away Arctic needs to be seen as nearby and relevant, and that climate change forecasts once seen as ‘uncertain,’ should instead be interpreted as ‘probable.’

“People are often confusing uncertainty with risk. If it’s uncertain they think they don’t really have to think about it. But there is a risk they take if they avoid things,” says Lemke. “a 40% chance could also mean a doubling of the risk, and a doubling of the risk is something that’s easily understood.”

“It’s a matter of how you communicate it,” says Lemke.

Perhaps Hollywood’s obsession with apocalyptic disaster narratives serves some kind of purpose after all—the stories seem outlandish, but films translate them into concepts we can understand and scenes we’re familiar with. It’s hard to picture what it would be like to live in a world that is 2°C warmer, but thanks to Hollywood special effects, we can picture what it would be like if storms of epic proportions engulfed the Statue of Liberty in a gigantic tidal wave.

“We have get down to people’s personal experience. That’s why I’m so against the use of things like global mean temperature, because people can’t relate to that,” says Slingo. “I am very keen on using narrative, but based on science, so people have access to the evidence for why we have this story that we tell about how climate change could affect them personally.”

Of course, we can’t give Hollywood too much credit: these stories are dangerously lacking input from actual climate science. Nevertheless, armed with the forecasting tools and technologies that have advanced so much over the past decade or so, we can counter uncertainty and get a better understanding of the risks we face. For example, using improved computer models and satellites that determine the age and thickness of ice, we can determine the rates of receding ice, and how much that will affect sea level rise in coastal communities.

Likewise, social media makes it easy to transmit information rapidly to a large audience that might not have been reachable otherwise. Reaching people where they are is of paramount importance—while scientists can put painstaking effort into presenting the most accurate, unbiased account of probable risks, this is just one facet of any given decision. In the end, it is the public and the policymakers that represent them that must make the decision about what actions to take, based on a complete narrative that includes the socioeconomic and cultural factors involved.

“It’s all about dialogue at the end of the day. One of the things I learned as MET office chief scientist was that based on the evidence I was giving to government, you would think that the policy would be quite clear,” says Slingo. “But there are other aspects to take into consideration, such as unemployment or other policy implementation capacities and societal implications.”

That’s why Lemke and Slingo both make huge efforts to communicate with the public, especially with the impressionable, optimistic, social media savvy and politically mobilizing younger generations. From their interactions and outreach with the public, Lemke and Slingo know that once you put climate change in proximity and translate science into narratives that are relevant to the lives of individual citizens, the public does care about climate change. They want to know more, and they want to do something about it.

When it comes to environmental advocacy, education is power, especially when it translates the high-end risk probabilities of climate science into relatable narratives. For Lemke and Slingo, that creates a huge opportunity for scientists of all backgrounds.

“I don’t think climate change has to be depressing. It’s a fantastic opportunity for a whole generation of scientists and engineers to tackle a great problem,” says Slingo. “I actually have the confidence that we’ll solve it.”

Jul 9, 2018 | Alumni, Communication, IIASA Network, South Africa, Systems Analysis, Young Scientists

By Sandra Ortellado, IIASA Science Communication Fellow 2018

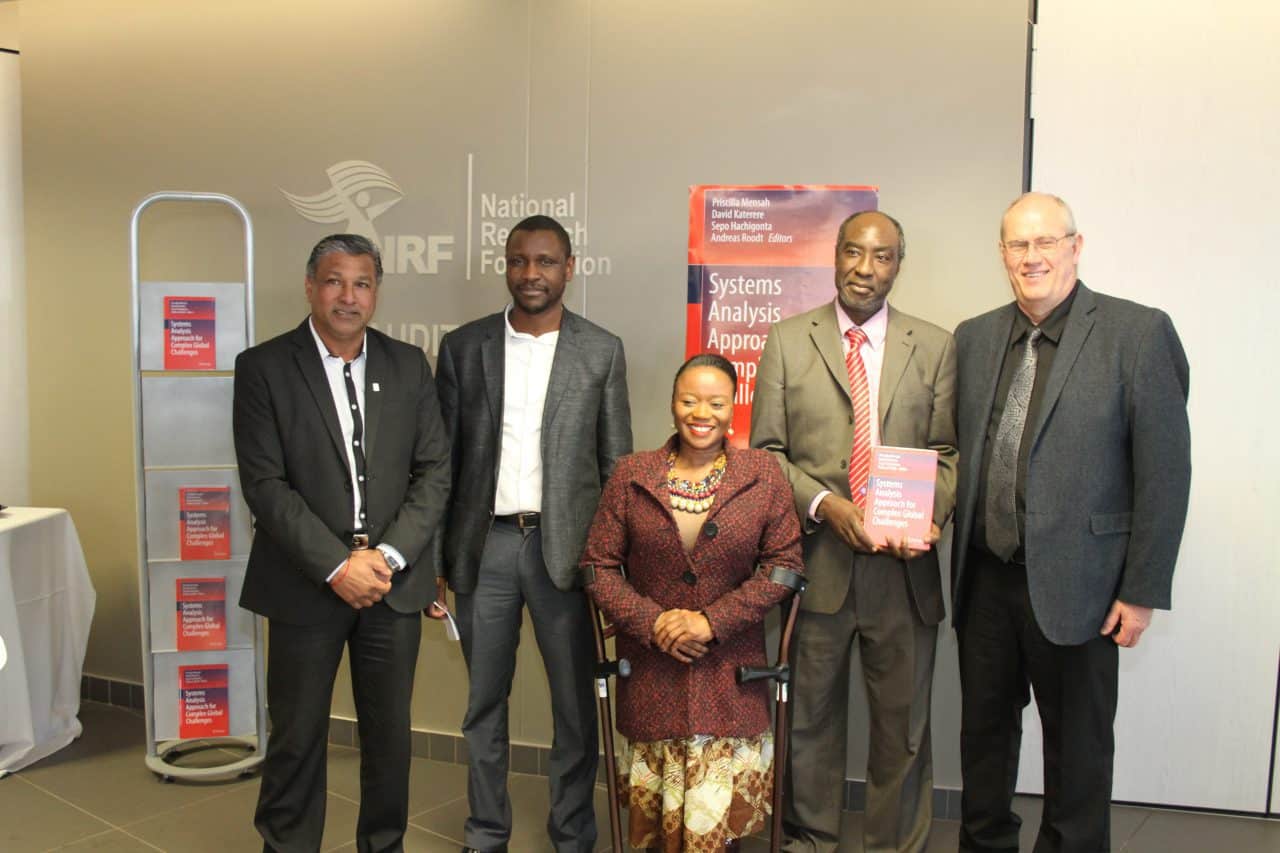

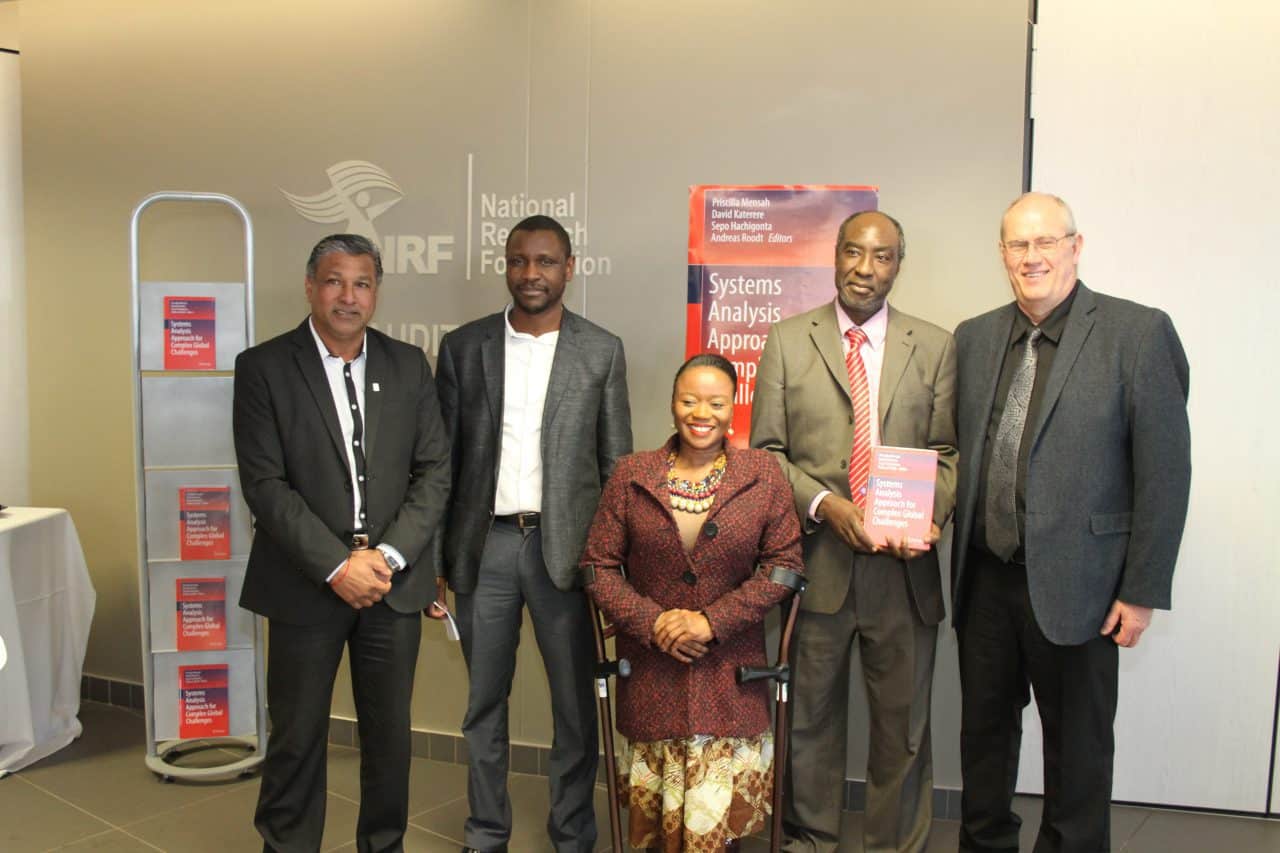

In 2007, Sepo Hachigonta was a first-year PhD student studying crop and climate modeling and member of the YSSP cohort. Today, he is the director in the strategic partnership directorate at the National Research Foundation (NRF) in South Africa and one of the editors of the recently launched book Systems Analysis for Complex Global Challenges, which summarizes systems analysis research and its policy implications for issues in South Africa.

From left: Gansen Pillay, Deputy Chief Executive Officer: Research and Innovation Support and Advancement, NRF, Sepo Hachigonta, Editor, Priscilla Mensah, Editor, David Katerere, Editor, Andreas Roodt Editor

But the YSSP program is what first planted the seed for systems analysis thinking, he says, with lots of potential for growth.

Through his YSSP experience, Hachigonta saw that his research could impact the policy system within his home country of South Africa and the nearby region, and he forged lasting bonds with his peers. Together, they were able to think broadly about both academic and cultural issues, giving them the tools to challenge uncertainty and lead systems analysis research across the globe.

Afterwards, Hachigonta spent four years as part of a team leading the NRF, the South African IIASA national member organization (NMO), as well as the Southern African Young Scientists Summer Program (SA-YSSP), which later matured into the South African Systems Analysis Centre. The impressive accomplishments that resulted from these programs deserved to be recognized and highlighted, says Hachigonta, so he and his colleagues collected several years’ worth of research and learning into the book, a collaboration between both IIASA and South African experts.

“After we looked back at the investment we put in the YSSP, we had lots of programs that were happening in South Africa, and lots of publications and collaboration that we wanted to reignite,” said Hachigonta. “We want to look at the issues that we tackled with system analysis as well as the impact of our collaborations with IIASA.”

Now, many years into the relationship between IIASA and South Africa, that partnership has grown.

Between 2012 and 2015, the number of joint programs and collaborations between IIASA and South Africa increased substantially, and the SA-YSSP taught systems analysis skills to over 80 doctoral students from 30 countries, including 35 young scholars from South Africa.

In fact, several of the co-authors are former SA-YSSP alumni and supervisors turned experts in their fields.

“We wanted to use the book as a barometer to show that thanks to NMO public entity funding, students have matured and developed into experts and are able to use what they learned towards the betterment of the people,” says Hachigonta. The book is localized towards issues in South Africa, so it will bring home ideas about how to apply systems analysis thinking to problems like HIV and economic inequality, he adds.

“It’s not just a modeling component in the book, it still speaks to issues that are faced by society.”

Complex social dilemmas like these require clear and thoughtful communication for broader audiences, so the abstracts of the book are organized in sections to discuss how each chapter aligns systems analysis with policymaking and social improvement. That way, the reader can look at the abstract to make sense of the chapter without going into the modeling details.

“Systems analysis is like a black box, we do it every day but don’t learn what exactly it is. But in different countries and different sectors, people are always using systems analysis methodologies,” said Hachigonta, “so we’re hoping this book will enlighten the research community as well as other stakeholders on what systems analysis is and how it can be used to understand some of the challenges that we have.”

“Enlightenment” is a poetic way to frame their goal: recalling the age of human reason that popularized science and paved the way for political revolutions, Hachigonta knows the value of passing down years of intellectual heritage from one cohort of researchers to the next.

“You are watching this seed that was planted grow over time, which keeps you motivated,” says Hachigonta.

“Looking back, I am where I am now because of my involvement with IIASA 11 years ago, which has been shaping my life and the leadership role I’ve been playing within South Africa ever since.”

Jun 29, 2018 | Communication, IIASA Network, United Kingdom, Women in Science

by Melina Filzinger, IIASA Science Communication Fellow

As a science communication fellow at IIASA, I had the opportunity to talk to Dame Anne Glover, who was recently made an IIASA distinguished visiting fellow. Originally a successful researcher in microbiology, she previously served as the first chief scientific adviser for Scotland, as well as the first chief scientific adviser to the president of the European Commission, and is now president of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

© Anne Glover

In your roles as scientific adviser you had to know about a broad range of relevant scientific topics. How do you keep informed about topics that lie outside your own area of research?

Of course no-one can be an expert in all the different areas of science. As a microbiologist, I am very specialized, but I am also a generalist when it comes to other areas of research. I keep up to date by reading articles about lots of different topics, from climate change to chemical toxicity or Alzheimer’s research, just because I am curious and interested.

However, if a minister or policymaker asked me to brief them on a particular topic, I would consult organizations with expertise in that area and ask them questions until I felt that I understood the topic. Then I would translate that scientific, often jargon-filled research into something that makes sense to a non-specialist. Part of the role as scientific adviser is not so much being an expert as being a translator.

Do you follow any science publications aimed at a broad audience? What are your favorites?

There is an organization called Sense about Science that publishes reports on issues that are being discussed among the public. They also have a fabulous service called Ask for evidence. Anyone can go onto their website and type a question, for example “Do female contraceptive pills end up feminizing fish in water streams?”, and they have a panel of experts that can comment on that, give you the evidence, and explain why this issue might or might not be a problem. It’s fantastic! I often use these answers as a starting point to find out about something.

I follow several other popular news outlets as well, for example New Scientist or the science and nature section of the BBC news app. I don’t expect absolute accuracy from those, I just expect to get a first impression of a research area. I also use Twitter as a source of information, because people often tweet about interesting science articles.

You are very active on Twitter. Has social media been useful to you, and how can it be used effectively?

I came to Twitter kicking and screaming when I joined the European Commission as chief scientific adviser to the president. I just thought that I had way too much to do to spend time on social media. It was Jan Marco Müller, a former colleague and now head of the directorate office at IIASA, who convinced me that Twitter could actually be a good way to tell people what I was doing, especially since transparency about my work is very important to me.

Have I found it useful? Enormously so! When I was at the commission I used it to see what really got people excited, either in a good way or in a bad way. When people were against a new technology, it helped me to understand their reasons. Tweeting is also an opportunity for me to help other people by highlighting interesting and useful events or initiatives. It can even be a little bit addictive.

How can science communicators and journalists reach a wide audience without oversimplifying scientific content?

The biggest nervousness I see among scientists is that of oversimplification. That is because, if you do oversimplify, you’re not going to upset your lay audience, but you will upset your scientific audience. I struggled with this for quite some time myself. Generally speaking, I would always favor simplification, of course not to the point of saying something that’s not true. I would however encourage scientists to be less afraid of simplification when speaking to a non-scientific audience. You will never be able to please everyone, you can only do your best to make an abstract subject accessible and interesting to people.

Do you have any tips for young scientists to make their work visible to the public?

In many cities there are science centers, museums, and other places where people get together, and there is nothing, other than their own modesty, to stop a young scientist from offering to talk about their work there. If it seems too daunting to do that kind of thing on your own, you could maybe do it with some of your colleagues. There are lots of opportunities out there for young scientists. Nobody is going to give those opportunities to you, but nobody is going to stop you either! You just have to take them!

If you do take them, think about what audience you are trying to reach beforehand, for example, if you want to talk to children or young adults. Then just be creative in how you present your research–try to build a story. Two good things will come out of it: one is that even if only 50 people show up, and only five of them are interested in what you are saying, you will have transformed the lives of those five people and made them excited about something. That is an achievement. The second thing is, that if you are doing things like that, and the young scientist next to you isn’t, it makes you different, and you have added value. You will also gain experience in communicating, which in turn will make the impact of your science much greater in the future. Everybody wins really, and it can be good fun as well.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Apr 26, 2018 | Communication

By Luke Kirwan, Open Access Manager at the IIASA Library

World Intellectual Property Day is celebrated annually on 26 April to bring a greater awareness of the role that intellectual property rights, such as copyright, patents, and industrial designs play in encouraging innovation and creativity. Unlike traditional property, intellectual property is intangible. It is far harder to protect one’s intellectual property from infringement or copying than it is to protect physical property. Intellectual property rights are important as, when well implemented, they provide the creator sufficient protection to benefit from their creation, but aren’t so stringent that they prevent widespread use.

Intellectual property refers to an individual’s original, intellectual creations, whether that is scientific, artistic, technical, or otherwise. As with other types of property, your intellectual property is covered by certain rights and protections automatically granted to the creator. These convey upon the owner rights over the control and utilization of their intellectual output. Depending on the situation, your intellectual property rights will also be covered by one or more types of protection, varying from patents to trademarks. These types of protection are intended to prevent unauthorized use or piracy of intellectual property, and to confer upon the creator time-limited, exclusive rights to their intellectual output.

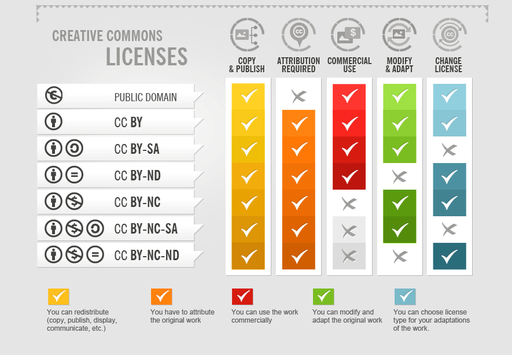

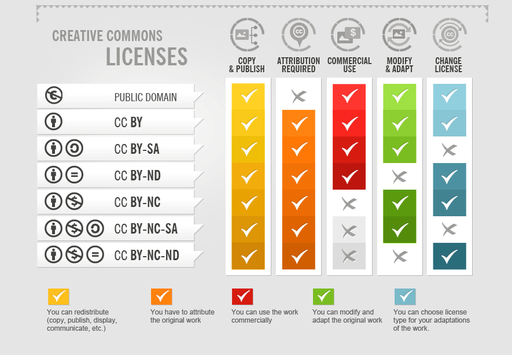

Creative commons licenses

When you write an article, that type of intellectual output is automatically covered by copyright. This is regulated through the Berne Convention. This convention confers a number of rights to the author, including the right to translate, make adaptations, and make reproductions of a work. Depending on the specific jurisdiction in which a work is created, copyright protection lasts for the lifetime of the creator plus a specific period (circa 50 to 70 years). In terms of producing a scientific article, one of the most important rights conferred upon an author by copyright protections is the right to sell or transfer these rights to another individual. Usually, when an author publishes an article with a journal, they sign a contract ceding their copyright to the publisher. Depending on the individual publisher, the author may retain some rights, such as the ability to distribute an earlier version of their paper and the right to proper attribution. However, the journal now has control of the dissemination, distribution, translation, and reproduction rights, among others.

Creative Commons licenses are designed to assist you in keeping your research openly accessible and distributable. For a creative commons license, the author retains all of the copyright, but has licensed their work for use and reuse under different circumstances, depending on the license. When publishing a paper under a creative commons license, rather than transferring the copyright to the publisher, the author instead licenses certain rights to the publisher to allow them to distribute the work. Creative commons licenses run from CC-0, which leaves a work completely free to reuse, redistribute, alter, and utilize in any manner, to CC-BY-NC-ND, which makes a work accessible, but restricts redistribution and commercial use. Similarly some license types employ an additional stipulation known as copyleft. In terms of a creative commons license this is known as share-alike. Essentially copyleft licensing allows people to freely distribute copies and modified versions as long as they adhere to the original licensing.

If you wish to make a paper open access, a journal will usually charge an Article Processing Charge (APC). However, the IIASA library maintains agreements with several publishers that allow a work to be made open access without charge. In instances where no waiver is in place, we also have an open access fund from which IIASA researchers can apply to have part of the APC charges paid for.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Aug 23, 2017 | Communication

Michaela Maier is a professor of applied communication psychology at the Institute of Communication and Media Psychology, University of Koblenz-Landau, Germany. Her work spans many forms of communication from crisis to election coverage to participatory decision making. She talks to IIASA Science Writer and Editor Daisy Brickhill.

Why is it important to communicate scientific uncertainty?

For us as researchers scientific uncertainty is something very natural that we consider all the time. We assess things like quality of samples used or numbers of replications, we justify and evaluate our research by taking into account a wider body of literature that may or may not show similar results. However, the degree of scientific uncertainty is not something that the public is so aware of. It is quite likely that it has not have been part of their education to learn the methods of evaluating the degree of (un)certainty of scientific evidence.

© Michaela Maier

Despite that, the public will almost definitely experience situations where they will have to evaluate uncertainty. As patients they might have to give their consent to a new medical treatment; as consumers they might need to decide whether to buy products that include, say, nanotechnology or genetically modified plants. Also as citizens—scientific evidence is relevant to many political decisions and as a voter you have to decide about these policies on election day. There are many situations where laypeople have to make judgements based on scientific findings—and we should communicate about the (un)certainty of this evidence in terms that people can understand.

Communicating uncertainty and how it works in one field or for one result can also give people the tools to understand and make judgments about other cases. Uncertainty can cover many things – is the sample large enough to draw any firm conclusions? Is it really representative of the whole population you are interested in?

When communicating complex topics, scientists and journalists can be nervous that talking about uncertainty will undermine the public’s interest or trust in the research – you’ve done some research on this?

Yes, we used communication of uncertainty around the safety of nanotechnology as a case study. Before the experiment we asked the participants a series of questions on how interested they were in science in general, in getting engaged in citizen science projects for example, or how likely they were to go to science museums. We also asked about their trust in scientists using measures of their perceptions of scientists’ competence, willingness to protect the public from technological risks, and honesty. We then sent them media reports over the course of six weeks, and after that we gave them the surveys again.

We found that communicating uncertainty didn’t undermine interest in science. In fact, what we found was that for a certain group of people the interest in science increased when uncertainty was discussed in the media reports they read. These people have what is called a low ‘need for cognitive closure.’ This means they are more open-minded and have a willingness to consider new or inconsistent information.

And did it undermine trust?

Communicating uncertainty didn’t seem to make any difference to the level of trust in scientists in people with either high or low need for cognitive closure. Ultimately our work showed that you won’t harm interest in science or trust in scientists by communicating uncertainty. It might not make much difference to some people but for others they will become even more engaged. It’s a very positive message.

Outside of an experimental environment are there any ways of engaging people with these complex issues of uncertainty?

It’s certainly a challenge for us to find the right formats. Narrative structures are an important format to pursue I think. There is a lot of evidence that narrative structures—storytelling—help people deal with complex information and that they really learn from it. Narrative structures focus more on the characters, they have a storyline, they might give the audience a chance to identify with the researcher, for instance.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

You must be logged in to post a comment.